Gut Feelers and Blind Believers: a Comparative Analysis of Jewish Involvement in the Communist Party in New York City and London, 1935-1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nonprofit Security Grant Program Threat Incident Report

Nonprofit Security Grant Program Threat Incident Report: January 2019 to Present November 15, 2020 (Updated 02/22/2021) Prepared By: Rob Goldberg, Senior Director, Legislative Affairs [email protected] The following is a compilation of recent threat incidents, at home or abroad, targeting Jews and Jewish institutions (and other faith-based organization) that have been reported in the public record. When completing the Threat section of the IJ (Part III. Risk): ▪ First Choice: Describe specific terror (or violent homegrown extremist) incidents, threats, hate crimes, and/or related vandalism, trespass, intimidation, or destruction of property that have targeted its property, membership, or personnel. This may also include a specific event or circumstance that impacted an affiliate or member of the organization’s system or network. ▪ Second Choice: Report on known incidents/threats that have occurred in the community and/or State where the organization is located. ▪ Third Choice: Reference the public record regarding incidents/threats against similar or like institutions at home or abroad. Since there is limited working space in the IJ, the sub-applicant should be selective in choosing appropriate examples to incorporate into the response: events that are most recent, geographically proximate, and closely related to their type or circumstance of their organization or are of such magnitude or breadth that they create a significant existential threat to the Jewish community at large. I. Overview of Recent Federal Risk Assessments of National Significance Summary The following assessments underscore the persistent threat of lethal violence and hate crimes against the Jewish community and other faith- and community-based institutions in the United States. -

2010-2011 Newsletter

Newsletter WILLIAMS G RADUATE PROGRAM IN THE HISTORY OF A RT OFFERED IN COLLABORATION WITH THE CLARK ACADEMIC YEAR 2010–11 Newsletter ••••• 1 1 CLASS OF 1955 MEMORIAL PROFESSOR OF ART MARC GOTLIEB Letter from the Director Greetings from Williamstown! Our New features of the program this past year include an alumni now number well over 400 internship for a Williams graduate student at the High Mu- going back nearly 40 years, and we seum of Art. Many thanks to Michael Shapiro, Philip Verre, hope this newsletter both brings and all the High staff for partnering with us in what promises back memories and informs you to serve as a key plank in our effort to expand opportuni- of our recent efforts to keep the ties for our graduate students in the years to come. We had a thrilling study-trip to Greece last January with the kind program academically healthy and participation of Elizabeth McGowan; coming up we will be indeed second to none. To our substantial community of alumni heading to Paris, Rome, and Naples. An ambitious trajectory we must add the astonishingly rich constellation of art histori- to be sure, and in Rome and Naples in particular we will be ans, conservators, and professionals in related fields that, for a exploring 16th- and 17th-century art—and perhaps some brief period, a summer, or on a permanent basis, make William- sense of Rome from a 19th-century point of view, if I am al- stown and its vicinity their home. The atmosphere we cultivate is lowed to have my way. -

Variation in Form and Function in Jewish English Intonation

Variation in Form and Function in Jewish English Intonation Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rachel Steindel Burdin ∼6 6 Graduate Program in Linguistics The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Professor Brian D. Joseph, Advisor Professor Cynthia G. Clopper Professor Donald Winford c Rachel Steindel Burdin, 2016 Abstract Intonation has long been noted as a salient feature of American Jewish English speech (Weinreich, 1956); however, there has not been much systematic study of how, exactly Jewish English intonation is distinct, and to what extent Yiddish has played a role in this distinctness. This dissertation examines the impact of Yiddish on Jewish English intonation in the Jewish community of Dayton, Ohio, and how features of Yiddish intonation are used in Jewish English. 20 participants were interviewed for a production study. The participants were balanced for gender, age, religion (Jewish or not), and language background (whether or not they spoke Yiddish in addition to English). In addition, recordings were made of a local Yiddish club. The production study revealed differences in both the form and function in Jewish English, and that Yiddish was the likely source for that difference. The Yiddish-speaking participants were found to both have distinctive productions of rise-falls, including higher peaks, and a wider pitch range, in their Yiddish, as well as in their English produced during the Yiddish club meetings. The younger Jewish English participants also showed a wider pitch range in some situations during the interviews. -

Irish Foreign Affairs

Irish Foreign Affairs Volume 9, Number 2 June 2016 “Every nation, if it is to survive as a nation, must study its own history and have a foreign policy” —C.J. O’Donnell, The Lordship of the World, 1924, p.145 Contents Editorial: Hiroshima p. 2 The 1938 Capture and San Pedro Imprisonment of Frank Ryan Manus O’Riordan p. 7 The Breaking of British Imperial and Financial Power 1940 – 1945 Feargus O Raghallaigh p. 11 Thoughts on Lord Esher (Part Three) Pat Walsh p. 14 James Connolly and the Great War Why Connolly and Larkin Supported Socialist Germany in World War 1 Pat Muldowney p.17 Habsburgia and the Irish: Postscript Pat Muldowney p.20 Documents Domenico Losurdo The Germans: A Sonderweg of an Irredeemable Nation? Part 2 p. 21 Submission by Jews for Justice for Palestinians to the Chakrabarti Inquiry into anti-Semitism and other Forms of Racism within the Labour Party. p. 27 A Quarterly Review published by the Irish Political Review Group, Dublin Editorial Hiroshima The President—that is the President of the World—visited the editorial material included in the Athol Books reprint of Hiroshima, where the modern world began on 6th August 1945. Bolg An Tsolair, the Gaelic magazine of the United Irishmen.) He said he did not go there to apologise. Why did he go? To formalise the precedent set by the nuclear bombing to It was Jefferson, the democrat of early US history, who establish that the deliberate killing of civilians of an enemy proclaimed sovereignty over the entire territory to the Pacific country for a political purpose is a legitimate, and even a while great tracts of it were still populated by natives, and commendable military tactic? What other purpose could there he warned that they would be exterminated if they resisted have been for the visit, since the notion that it might have been progress. -

Connolly in America: the Political Development of an Irish Marxist As Seen from His Writings and His Involvement with the American Socialist Movement 1902-1910

THESIS UNIVERSITY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE JAMES CONNOLLY IN AMERICA: THE POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT OF AN IRISH MARXIST AS SEEN FROM HIS WRITINGS AND HIS INVOLVEMENT WITH THE AMERICAN SOCIALIST MOVEMENT 1902-1910 by MICHEÁL MANUS O’RIORDAN MASTER OF ARTS 1971 A 2009 INTRODUCTION I have been most fortunate in life as regards both educational opportunities and career choice. I say this as a preface to explaining how I came to be a student in the USA 1969-1971, and a student not only of the history of James Connolly’s life in the New World a century ago, but also a witness of, and participant in, some of the most momentous developments in the living history of the US anti-war and social and labour movements of 40 years ago. I was born on Dublin’s South Circular Road in May 1949, to Kay Keohane [1910-1991] and her husband Micheál O’Riordan [1917- 2006], an ITGWU bus worker. This was an era that preceded not only free third-level education, but free second-level education as well. My primary education was received in St. Kevin’s National School, Grantham Street, and Christian Brothers’ School, Synge Street. Driven to study - and not always willingly! - by a mother who passionately believed in the principle expounded by Young Irelander Thomas Davis – “Educate, that you may be free!” - I was fortunate enough to achieve exam success in 1961 in winning a Dublin Corporation secondary school scholarship. By covering my fees, this enabled me to continue with second-level education at Synge Street. In my 1966 Leaving Certificate exams I was also fortunate to win a Dublin Corporation university scholarship. -

The Communal Life of the Sephardic Jews in New York City.Pdf

LOUIS M. HACKER SEPHARDIC JEWS IN NEW YORK CITY not having the slightest desire in the amend the federal acts would be to tween Sephardim and Ashkenazim Aegean. It must be apparent, then, world of becoming acquainted with have everything relating to the pre are more or less familiar; their beai-- that language difficulties stand as the police powers of either state or vention of conception stricken out of ing upon the separatism typical of insuperable obstacles in the path of a federal governments, the average the obscenity laws; another way * the life of the Oriental Jew will at common understanding between Se doctor and druggist are quite wary would be by permissive statute ex once be grasped. It is common phardim and Ashkenazim—at least, of the whole subject. The federal empting from their provisions the knowledge that the Sephardim speak of the first immigrant generations. laws, however, apply not only to the medical and public health professions Hebrew with a slightly different ac The habits of the life of the Se article or agent used in the prevent in the discharge of their duties. If cent, employ synagogue chants which phardim and their general psychology ion of conception, but also to all in the former method were adopted it may be described as Oriental in tone present other reasons for the exist formation on the subject. Such being would in effect throw the mails and rather than Germanic or Slavic, and ence of a real separatism. Coming the case, it is not possible for a doctor common carriers in interstate com have incorporated into their prayer- from the Levant as they have, the Se to obtain books dealing with the sci merce wide open to the advertisement bocks many liturgical poems unfamil phardim have brought a mode of life entific side of Birth Control, nor can and sale of spurious contraceptive in iar to the Ashkenazic ritual. -

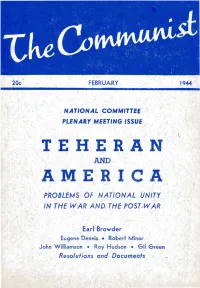

Earl Browder F I Eugene Dennis • Robert Minor John Willia-Mson • Roy · Hudson • Gil G R,Een Resolutions And.· Documents I • I R

I . - > 20c FEBRUARY 1944 ' .. NATIONAL COMMITTE~ I PLENARY MEETING ISSUE ,. - • I ' ' ' AND PROBLEMS OF NATIONAL UNIT~ ' ·- ' . IN THE WAR AND THE POST-~AR I' • Earl Browder f I Eugene Dennis • Robert Minor John Willia-mson • Roy · Hudson • Gil G r,een Resolutions and.· Documents I • I r / I ' '. ' \' I , ... I f" V. I. L~NIN: A POLITICAL, BIOGRAP,HY 1' ' 'Pre pared by' the Mc);;·Engels.Le nin 'Institute, t his vo l ' ume provides b new ana authoritative 'study of t he life • and activities of the {9under and leader of the Soviet . Union up to thf;l time of Le11i n's death. P r.~ce $ 1.90 ~· .. • , f T'f'E RED ARMY By .Prof. I. Mi111. , The history and orgon lfqtion of the ~ed Army ·.and a iJt\fO redord1of its ~<;hievem e nfs fr9 m its foundation fhe epic V1cfory ,tal Stalingrad. Pl'i ce $1.25 I SOVIET ECONOMY AND !HE WAR By Dobb ,. ' Maur fc~ • ---1· •' A fadyal record of economic developm~nts during the last .few years with sp6""cial re?erence ..to itheir bearing '/' / on th~ war potentiaJ··and· the needs of the w~r. Price ~.25 ,- ' . r . ~ / .}·1 ' SOVIET PLANNING A~ D LABOR IN PEACE AND WAR By Maurice Oobb ' ' 1 - I A sh~y of economic pl~nning, the fln~ncia l . system, ' ' ' . work , wages, the econorpic effects 6f the war, end other ' '~>pecial aspects of the So'liet economic system prior to .( and during the w ~ r , · Price ·$.35 - I ' '-' I I • .. TH E WAR OF NATIONAL Llij.E R ATIO~ (in two· parts) , By Joseph ·stalin '· A collecfion of the wa~fime addr~sses of the Soviet - ; Premier and M<~rshal of the ·Rep Army, covering two I years 'o.f -the war ~gains+ the 'Axis. -

17-CV-01854 19840629__Doc.Pdf (7.091Mb)

, . , . , ' H8f lll!IAMll!I 18 Mlil&I tlM'18Ultd1' S ..CCRET · UNITED .6TATE6 ' ' 60UTfIEQN COMMAND Headquarters U.S. Southern Command Chief of Staff, Major General Jon A. Norman, USAF Date: 25 JAN 2018 Authority: EO 13526 Declassify:_ Deny in Full: _ Declassify in Part: _X_ Reason: Sec. 3.3(b)(1); (b)(6) MOR: SC 16-026-MOR; (150 pages) 1983 tl16TOQICAL QEPOQT (U) CLASS IFIED BY USCI'NCSO COPY if.3 Oft 1-COP_I ES -, REV IEW ON l JULY 1990 SECRET SC 001 .NOT ·,,1astse1,1· IO IOIIIGN .........,.. ·stCRET N0F8RN TlfIS PAGE INTENTIONAllY LEFT BLANK ,;· SEBRET N9F8RN SC 002 SESRET .53 MM. ._ . s::1. El] P !Ud. 7 3 . DEPARTMENT OF' DEFENSE INYilJaTAtts SQU"fiaN ~g 1 ·no. AP0-3"'°""' =:so, SCJ3 . 29 June 1984 SUBJECT: Annual Historical Report, 1983 SEE DISTRIBUTION -~ - 1. Forwarded herewith 1s the US Southern Command Historical Report for 1983. > . ..:: 2. When separated from the classified inclosure, this letter is regarded UNCLASS IFIEO. FOR IBE COMMANDER IN CHIEF: (b)(6) 1 Incl as · OISTRISUTION: JCS, Washington, DC 20301 16 CINCAD, · l'eterson AFB, CO 80914 1 HQ USSOUTHCOM 15 CINCLANT, Norfolk, VA 23511 l SCJ1/J4 2 CINCMAC, Scott AFB, IL 62225 1 SCJ2 1 CINCPAC, Honolulu, HI 96823 1 SCJ3 10 use INC RED, MacDi11 AFB, FL 33608 1 SCJS l USCIHCCENT, Mac0i11 AFB, FL 33608 1 SCJ6 1 CINCSAC, Offutt AFB, NE 68113 1 CSA, Washington, DC 20301 3 TOTAL 67 CNO, Washington, DC 20301 3 CSAF, Washington, DC 20301 3 COR, USA FORSCOM, Ft McPherson. GA 30330 1 CDR, USAF TAC, Lang1ey AFB, VA 23365 1 President, National Defense University, ATTN:· NDU-LO, Washington, DC 20319 2 CMOT, USA War College, Carlis1e Bks, PA 17103 1 CMDT . -

“Brothers and Sisters of Work and Need”: the Bundist Newspaper Unzer Tsayt and Its Role in New York City, 1941-1944

“Brothers and Sisters of Work and Need”: The Bundist Newspaper Unzer Tsayt and its Role in New York City, 1941-1944 Saul Hankin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 3, 2013 Advised by Professor Scott Spector TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................... ii Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: Convergent Histories: Jewish Socialism in New York City and in Eastern Europe, 1881-1941 ................................................................................. 9 Chapter Two: The Bundist Past and Present: Historiography and Holocaust in Unzer Tsayt .......................................................................................................... 29 Chapter Three: Solving the “Jewish Question”: Anti-Zionism in Unzer Tsayt ....... 49 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 72 Bibliography ................................................................................................................... 77 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincere thanks go to the following people and institutions that made this thesis possible: Professor Scott Spector, my thesis advisor, in particular for always encouraging me to engage more with primary -

Read the Excellent Thesis Here

"You fight your own wars. Irish defence of the Spanish Republic at war. 1936-1939." Ms Aude Duche Univeriste de Haute Bretagne Rennes, France Masters thesis, 2004 Thanks to Aude for her permission to add this thesis to the site. http://www.geocities.com/irelandscw/pdf-FrenchThesis.pdf The conversation to a pdf format has altered the layout of her excellent piece of work. Ciaran Crossey, Belfast, Added online, 28th January 2007 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 3 PART I – THE IRISH LEFT AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR.......................................................... 5 THE IRISH LEFT IN THE 1930S................................................................................................................ 5 . Origins............................................................................................................................................ 5 1926-1936: the revival of the left..................................................................................................... 8 … remaining marginal.................................................................................................................. 11 THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR.................................................................................................................... 13 The Spanish Republic .................................................................................................................... 13 Enemies of the Republic -

2001-; Joshua B

The Irish Labour History Society College, Dublin, 1979- ; Francis Devine, SIPTU College, 1998- ; David Fitzpat- rick, Trinity College, Dublin, 2001-; Joshua B. Freeman, Queen’s College, City Honorary Presidents - Mary Clancy, 2004-; Catriona Crowe, 2013-; Fergus A. University of New York, 2001-; John Horne, Trinity College, Dublin, 1982-; D’Arcy, 1994-; Joseph Deasy, 2001-2012; Barry Desmond, 2013-; Francis Joseph Lee, University College, Cork, 1979-; Dónal Nevin, Dublin, 1979- ; Cor- Devine, 2004-; Ken Hannigan, 1994-; Dónal Nevin, 1989-2012; Theresa Mori- mac Ó Gráda, University College, Dublin, 2001-; Bryan Palmer, Queen’s Uni- arty, 2008 -; Emmet O’Connor, 2005-; Gréagóir Ó Dúill, 2001-; Norah O’Neill, versity, Kingston, Canada, 2000-; Henry Patterson, University Of Ulster, 2001-; 1992-2001 Bryan Palmer, Trent University, Canada, 2007- ; Bob Purdie, Ruskin College, Oxford, 1982- ; Dorothy Thompson, Worcester, 1982-; Marcel van der Linden, Presidents - Francis Devine, 1988-1992, 1999-2000; Jack McGinley, 2001-2004; International Institute For Social History, Amsterdam, 2001-; Margaret Ward, Hugh Geraghty, 2005-2007; Brendan Byrne, 2007-2013; Jack McGinley, 2013- Bath Spa University, 1982-2000. Vice Presidents - Joseph Deasy, 1999-2000; Francis Devine, 2001-2004; Hugh Geraghty, 2004-2005; Niamh Puirséil, 2005-2008; Catriona Crowe, 2009-2013; Fionnuala Richardson, 2013- An Index to Saothar, Secretaries - Charles Callan, 1987-2000; Fionnuala Richardson, 2001-2010; Journal of the Irish Labour History Society Kevin Murphy, 2011- & Assistant Secretaries - Hugh Geraghty, 1998-2004; Séamus Moriarty, 2014-; Theresa Moriarty, 2006-2007; Séan Redmond, 2004-2005; Fionnuala Richardson, Other ILHS Publications, 2001-2016 2011-2012; Denise Rogers, 1995-2007; Eddie Soye, 2008- Treasurers - Jack McGinley, 1996-2001; Charles Callan, 2001-2002; Brendan In September, 2000, with the support of MSF (Manufacturing, Science, Finance – Byrne, 2003-2007; Ed. -

The Cultural Cold War the CIA and the World of Arts and Letters

The Cultural Cold War The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters FRANCES STONOR SAUNDERS by Frances Stonor Saunders Originally published in the United Kingdom under the title Who Paid the Piper? by Granta Publications, 1999 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2000 Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press oper- ates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in in- novative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450 West 41st Street, 6th floor. New York, NY 10036 www.thenewpres.com Printed in the United States of America ‘What fate or fortune led Thee down into this place, ere thy last day? Who is it that thy steps hath piloted?’ ‘Above there in the clear world on my way,’ I answered him, ‘lost in a vale of gloom, Before my age was full, I went astray.’ Dante’s Inferno, Canto XV I know that’s a secret, for it’s whispered everywhere. William Congreve, Love for Love Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................... v Introduction ....................................................................1 1 Exquisite Corpse ...........................................................5 2 Destiny’s Elect .............................................................20 3 Marxists at