Unseen Rain : Quatrains of Rumi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Lil Uzi Songs Download

Lil uzi songs download Continue Source:4,source_id:870864.object_type:4, id:870864,status:0,title:LIL U ULTRASOUND VERT,share_url:/artist/lil-uzi-vert,albumartwork: objtype:4 Thank you for showing interest in '. It is only available in India. Click here to go to the homepage or you'll be automatically redirected within 10 seconds. setTimeout (function) $'.'.artistDetailPage.artistAbout'). Download music from your favorite artists for free with Mdundo. Mdundo started in collaboration with some of Africa's best artists. By downloading music from Mdundo YOU to become part of the support of African artists!!! Mdundo is financially supported by 88mph - in partnership with Google for Entrepreneurs. Mdundo kicks the music into the stratosphere, taking the artist's side. Other mobile music services hold 85-90% of sales. What ?!, Yes, most of the money is in the pockets of major telecommunications companies. Mdundo lets you track your fans and we share any revenue earned from the site fairly with the artists. I'm a musician! - Log in or sign up for hip-hop August 2, 202015 September 2020 Olami Published in Hip Hop, TrendingTagged Future, Lil Uzi Vert1 Best Rap Song 2019Featuring Lil Uzi Vert, Doja Cat, and Young Thug, along with many exciting young upstarts 20 Best Rap Albums 2017 From Playboi Carti's muttering opus Vince Staples' delirium up deconstructed fame, is the most important rap record of the year. The 100 best songs of 2017 from Lord's ecstatic emotional purification to Frank Ocean's ode to cycling to the frantic knock of Cardi B, this is our pick for the best songs of the year. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

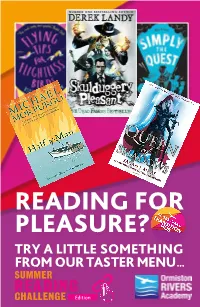

Reading for Pleasure? Try a Little Something from Our Taster Menu

READING FOR PLEASURE? TRY A LITTLE SOMETHING FROM OUR TASTER MENU... Edition Looking for something to read but don’t know where to begin? Dip into these pages and see if something doesn’t strike a spark. With over thirty titles (many of which come recommended by the organisers of World Book Day - including a number of best sellers), there is bound to be something to appeal to every taste. There is a handy, interactive contents page to help you navigate to any title that takes your fancy. Feeling adventurous? Take a lucky dip and see what gems you find. Cant find anything here? Any Google search for book extracts will provide lots of useful websites. This is a good one for starters: https://www. penguinrandomhouse.ca/books If you find a book you like, there are plenty of ways to access the full novel. Try some of the services listed below: Chargeable services Amazon Kindle is the obvious choice if you want to purchase a book for keeps. You can get the app for both Apple and Android phones and will be able to buy and download any book you find here. If you would rather rent your books, library style, SCRIBD is the best app to use. They charge £8.99 per month but you can get the first 30 days free and cancel at any time. If you fancy listening to your favourite stories being read to you by talented voice recording artists and actors, tryAudible : they offer both one off purchases and subscription packages. Free services ORA provides access to myON and you will have already been given details for how to log in. -

My Favorite Rumi

My Favorite Rumi selected by Jason Espada 1 Preface In the early 1980’s, I had the incomparable good fortune of finding Rumi’s poetry. Since that time, it’s been a faithful companion; at times a stern teacher, and most often, just the right, delightful medicine. Like a letter from a dear friend, it has always been Rumi’s poetry that reminds me the most of my true home. These last couple of years I’ve had the thought of assembling my favorite Rumi to share with both fellow lovers of his poetry, and especially those who have never read or even heard of him. I’ve been able to make shorter collections of the poetry of Hafiz and Pablo Neruda, to share with others, but with Rumi it’s been more of a challenge. For one thing, I have more of his poetry to choose from. But more than this, Rumi is the poet who is closest to my own heart, and so naturally I really want to get this right. At some point though, not being able to do something perfectly is no excuse for not acting. This is the best I can do right now, and so I send this out into the world with the wish that others receive at least some of the same joy, nourishment and inspiration I have over the years. Who knows? Dear reader, perhaps meeting Rumi’s poetry, the door will open for you, and all the riches he encourages us to know will be yours. It’s with good reason that great works are always in season. -

Rumi Contents Volume 1

Contents In the Beginning 7 Gökalp Kâmil Editor’s Note 11 Leonard Lewisohn Love’s Freedom: A Ghazal from Rumi’s Divan-i Shams-i Tabrizi 16 Translated by Franklin Lewis From Balkh to the Mediterranean: Everyman, Rabbi Eisik, son of Yekel and Jalal al-Din Rumi’s Mathnawi 17 Jalil Nozari Mawlana Jalal al-Din Rumi of R. A. Nicholson 33 Marta Simidchieva Rumi’s Metaphysics of the Heart 69 Mohammed Rustom Don’t Sleep: A Ghazal from Rumi’s Divan-i Shams-i Tabrizi 80 Translated by Paul Losensky The Castle of God is the Centre of the Dervish’s Soul 82 Alberto Fabio Ambrosio The Human Beloved and the Divine Beloved in the Poetry of Mawlana Rumi 100 A. G. Rawan Farhadi The Religion of Love: One Ghazal and Two Quatrains by Rumi 108 Translated by Leonard Lewisohn The Popularity of Mawlana Rumi and the Mawlawi Tradition 109 Ibrahim Gamard The Final Generation: A Tahmîs-i Mutarraf by Ahmed Remzi Dede 122 Roderick Grierson 6 contents The Honey Bee: A Quatrain by Rumi 131 Translated by Michael Zand book reviews Mevlânâ Celâleddîn Rûmî, Mesnevi-i S,erîf S,erhi, trans. and commentary by Ahmed Avni Konuk, ed. Mustafa Tahralı, 13 vols. – Reviewed by Alberto Fabio Ambrosio 132 Seyed Ghahreman Safavi and Simon Weightman, Rumi’s Mystical Design: Reading The Mathnawi, Book One – Reviewed by Coleman Barks 136 Shams-i Tabrizi, Rumi’s Sun: The Teachings of Shams of Tabriz, trans. Refik Algan and Camille Adams Helminski – Reviewed by Mojdeh Bayat and Ali Jamnia 138 Rumi, The Quatrains of Rumi: Rubaciyat-é Jalaluddin Muhammad Balkhi-Rumi; Complete Translation with Persian Text, Islamic Mystical Commentary, Manual of Terms, and Concordance, trans. -

Apparently Irreligious Verses in the Works of Mawlana Rumi by Ibrahim

Apparently Irreligious Verses in the Works of Mawlana Rumi By Ibrahim Gamard About Dar-Al- Masnavi Mystics sometimes surprise or shock listeners by statements that appear on the surface The Mevlevi Order to be irreligious, heretical, blasphemous, or radically tolerant--but which are expressions Masnavi of profound wisdom when understood on a deeper level. This is, in part, due to the frustration of trying to communicate mystical understanding to those whose minds are Divan restricted by conventional thinking. It is part of the playful teaching style of some mystics Prose Works to use unconventional statements to open such minds to deeper truths. In the case of orthodox religious mystics, radical-sounding statement are consistently harmonious with Discussion Board religious precepts when undertood at the level intended. Contact Such is the case in the poetic works of Mawlânâ Rûmî, the great Muslim mystic of the Links 13th century C. E. His references to things forbidden to Muslims such as "idols," "wine," Home and "unbelief" are not particularly provocative, in most cases, because these were commonplace images used in Persian Sufi poetry centuries before his time, understood to be spiritual metaphors by educated Persian listeners and readers. Nevertheless, the use of such imagery has continued to be misunderstood by Muslims and non-Muslims down to the present time. Further confusion has been caused by current popularizers of his poetry, who are eager to portray Mawlânâ as a radical mystic who defied "fundamentalist" Muslim authorities by teaching heretical doctrines, drinking alcoholic beverages, welcoming students affiliated with other religions, and so on. As a result, some of Mawlânâ's major teachings are all too often not understood correctly. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

Jalal Al-Din Rumi's Poetic Presence and Past

“He Has Come, Visible and Hidden” Jalal al-Din Rumi’s Poetic Presence and Past Matthew B. Lynch The University of the South, USA Jalal al-Din Rumi (Jalal¯ al-Dın¯ Muh.ammad Rum¯ ı)¯ is best known as a mystic poet and promulgator of the Suftradition of Islam. During his lifetime, Jalal al-Din Rumi was a teacher in Islamic religious sciences, a prolifc author, and the fgurehead of a religious community that would come to be known as the Mevlevi Suforder. His followers called him “Khodavandgar” (an honorifc meaning “Lord”) or “Hazrat-e Mawlana” (meaning the “Majesty of Our Master,” often shortened to “Mawlana,” in Turkish rendered as “Mevlana”) (Saf 1999, 55–58). As with his appellations, the legacy and import of Rumi and his poetry have been understood in a variety of forms. Jalal al-Din Rumi’s renown places him amongst the pantheon of great Persian-language poets of the classical Islamicate literary tradition that includes Hafez (see Hafez of Shi- raz, Constantinople, and Weltliteratur), Sadi, Attar, Nezami (see Nizami’s Resonances in Persianate Literary Cultures and Beyond), and Ferdowsi (see The Shahnameh of Ferdowsi). While all of these poets produced large bodies of literature, Rumi’s writing differs some- what in the circumstances of its production. His poetry was composed in front of, and for the sake of, a community of murids (murıds¯ ), or pupils, who relied on Rumi for his mystical teachings related to the articulation of Islam through the lens of love of the divine. At times, he delivered his ghazal (see The Shahnameh of Ferdowsi) poetry in fts of ecstatic rapture. -

Sufism and Music: from Rumi (D.1273) to Hazrat Inayat Khan (D.1927) Grade Level and Subject Areas Overview of the Lesson Learni

Sufism and Music: From Rumi (d.1273) to Hazrat Inayat Khan (d.1927) Grade Level and Subject Areas Grades 7 to 12 Social Studies, English, Music Key Words: Sufism, Rumi, Hazrat Inayat Khan Overview of the lesson A mystic Muslim poet who wrote in Persian is one of American’s favorite poets. His name is Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi (1207-1273), better known a Rumi. How did this happen? The mystical dimension of Islam as developed by Sufism is often a neglected aspect of Islam’s history and the art forms it generated. Rumi’s followers established the Mevlevi Sufi order in Konya, in what is today Turkey. Their sema, or worship ceremony, included both music and movement (the so-called whirling dervishes.) The Indian musician and Sufi Hazrat Inayat Khan (1882-1927) helped to introduce European and American audiences to Sufism and Rumi’s work in the early decades of the twentieth century. This lesson has three activities. Each activity is designed to enhance an appreciation of Sufism as reflected in Rumi’s poetry. However, each may also be implemented independently of the others. Learning Outcomes: The student will be able to: • Define the characteristics of Sufism, using Arabic terminology. • Analyze the role music played in the life of Inayat Khan and how he used it as a vehicle to teach about Sufism to American and European audiences. • Interpret the poetry of Rumi with reference to the role of music. Materials Needed • The handouts provided with this lesson: Handout 1; The Emergence of Sufism in Islam (featured in the Handout 2: The Life and Music of Inayat Khan Handout 3: Music in the Poems of Rumi Author: Joan Brodsky Schur. -

Zoo Alicia Cotsoradis Depauw University

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 4-2018 Zoo Alicia Cotsoradis DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Cotsoradis, Alicia, "Zoo" (2018). Student research. 82. https://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch/82 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zoo: By Alicia Cotsoradis DePauw University Honor Scholar Program Class of 2018 Sponsor: Ronald Dye Committee: Rebecca Bordt, Jeffrey McCall, Robert Stevens 1 Table of Contents The Beginning………………………………..3 Sister………………………………………...12 School………………………………………..20 Crime………………………………………..22 First Stint in Prison………………………..29 Prison Take Two…………………………...32 Zoo………………………………………….....38 Admissions……………………………………...40 Black, and Brown, and Polar Beasts, Oh My….47 Parrots…………………………………………..53 Intake………………………………………...…..60 The Jumbo Beasts……………………………..67 Picture Day……………………………………..74 The Aftermath……………………………………..81 The Petting Zoo…………………………………..86 Worker Beasts………………………………..93 Big Game Hunting Safari…………………………..103 The Grand Escape……………...……………114 On the News…………………………………..120 The End…………………...……………….120 Goodbye…………………………….……...130 2 The Beginning My name is Ray, but my name won’t matter once you see my face. You see, I’m scary. I’m the monster that hides in your kid’s closet at night, just waiting to pop out and yell boo. I’m danger, and not the sexy kind. You know, the devilish looking man who rides up on a motorcycle only to whisk you off your feet, then leaves you choking on your own breath. -

James Pitts – 1

File 1-1 0:00:00.0 Then he asked me later on, two, three, four years after that, he mentioned it again. I asked him, I said, “Are you sure that’s what you want?” He said, “Yeah.” I said, “Well, I ain’t makin’ a promise that I might not be able to keep, but I’ll put some stipulations in it, a possibility.” I said— 0:00:20.8 End file 1-1. File 1-2 0:00:00.0 —and I finished ninth grade at Stringtown [?]. Well, I said I finished it. I went. At the end of the school year I got an award for being an occasional ___ student. So the next year I quit. I had to put in the crops, and I stayed there about two years, and I went to my granddad’s. ‘Cause we walked miles one way to catch the—little over three miles, ‘bout three and a quarter miles to catch the bus and had to be there about 10 minutes to 7 in the mornin’ and then ride it several miles into school. And had three different creeks to cross, and they didn’t have bridges over ‘em, and sometimes that was ___, and sometimes I just didn’t want to go. So anyway, then I went back and I started in the tenth, and I never did go pick up my grades or report cards, so I don’t even know if I passed the ninth or not. But anyway— (What year was that?) 0:01:03.8 That’s—I have a great memory.