MTO 19.3: Boone, Mashing: Toward a Typology of Recycled Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Beatles Albums Identification Guide Updated: 22 De 16

Canadian Beatles Albums Identification Guide Updated: 22 De 16 Type 1 Rainbow Label Capitol Capitol Records of Canada contracted Beatlemania long before their larger and better-known counterpart to the south. Canadian Capitol's superior decision-making brought Beatles records to Canada in early 1963. After experimenting with the release of a few singles, Capitol was eager to release the Beatles' second British album in Canada. Sources differ as to the release date of the LP, but surely by December 2, 1963, Canada's version of With the Beatles became the first North American Beatles album. Capitol-USA and Capitol-Canada were negotiating the consolidation of their releases, but the US release of The Beatles' Second Album had a title and contained songs that were inappropriate for Canadian release. After a third unique Canadian album, album and single releases were unified. From Something New on, releases in the two countries were nearly identical, although Capitol-Canada continued to issue albums in mono only. At the time when Beatlemania With the Beatles came out, most Canadian pop albums were released in the "6000 Series." The label style in 1963 was a rainbow label, similar to the label used in the United States but with print around the rim of the label that read, "Mfd. in Canada by Capitol Records of Canada, Ltd. Registered User. Copyrighted." Those albums which were originally issued on this label style are: Title Catalog Number Beatlemania With the Beatles T-6051 (mono) Twist and Shout T-6054 (mono) Long Tall Sally T-6063 (mono) Something New T-2108 (mono) Beatles' Story TBO-2222 (mono) Beatles '65 T-2228 (mono) Beatles '65 ST-2228 (stereo) Beatles VI (mono) T-2358 Beatles VI (stereo) ST-2358 NOTE: In 1965, shortly before the release of Beatles VI, Capitol-Canada began to release albums in both mono and stereo. -

Sexism Across Musical Genres: a Comparison

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 6-24-2014 Sexism Across Musical Genres: A Comparison Sarah Neff Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Neff, Sarah, "Sexism Across Musical Genres: A Comparison" (2014). Honors Theses. 2484. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2484 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: SEXISM ACROSS MUSICAL GENRES 1 Sexism Across Musical Genres: A Comparison Sarah E. Neff Western Michigan University SEXISM ACROSS MUSICAL GENRES 2 Abstract Music is a part of daily life for most people, leading the messages within music to permeate people’s consciousness. This is concerning when the messages in music follow discriminatory themes such as sexism or racism. Sexism in music is becoming well documented, but some genres are scrutinized more heavily than others. Rap and hip-hop get much more attention in popular media for being sexist than do genres such as country and rock. My goal was to show whether or not genres such as country and rock are as sexist as rap and hip-hop. In this project, I analyze the top ten songs of 2013 from six genres looking for five themes of sexism. The six genres used are rap, hip-hop, country, rock, alternative, and dance. -

Royal Umd 0117E 18974.Pdf (465.4Kb)

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: SELECTED WORKS OF COMPOSERS ASSOCIATED WITH HOWARD UNIVERSITY Guericke Christopher Royal, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Chris Gekker School of Music Throughout its over 100 year history, Howard University has produced and attracted many talented composers of many musical genres. Limiting this project to any one genre or focus would have lessened the overall impact of the music they created and the inspiration that has been a lauded part of the institution. The project will demonstrate the various harmonic, melodic, rhythmic and emotional contributions of the selected composers through interpretation of their music on the trumpet. Composers have been connected to the university in three general ways: as students, alumni and faculty; as commissioned artists; and through the performance of their works by notable performers associated with Howard. The pieces selected for this project exemplify a wide range of musical expressions and compositional techniques, and hopefully have been presented in a way that allows the emotional impact of each piece to resonate in a unique fashion. The selected works tended to fall into the categories of A. Trumpet and Brass Works B. Spirituals/ Meditational/ Religious Works C. Popular and Jazz Pieces D. Organ or other Instrumental Works E. Works of Historical Reference or Significance In some cases, certain pieces may be categorized across multiple categories (e.g. an organ piece based on religious material). As this was also a recording project, great care was taken during the recording process to capture as much emotional content as possible through stereo microphone techniques and the use of high quality equipment. -

The Effects of Digital Music Distribution" (2012)

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-5-2012 The ffecE ts of Digital Music Distribution Rama A. Dechsakda [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp The er search paper was a study of how digital music distribution has affected the music industry by researching different views and aspects. I believe this topic was vital to research because it give us insight on were the music industry is headed in the future. Two main research questions proposed were; “How is digital music distribution affecting the music industry?” and “In what way does the piracy industry affect the digital music industry?” The methodology used for this research was performing case studies, researching prospective and retrospective data, and analyzing sales figures and graphs. Case studies were performed on one independent artist and two major artists whom changed the digital music industry in different ways. Another pair of case studies were performed on an independent label and a major label on how changes of the digital music industry effected their business model and how piracy effected those new business models as well. I analyzed sales figures and graphs of digital music sales and physical sales to show the differences in the formats. I researched prospective data on how consumers adjusted to the digital music advancements and how piracy industry has affected them. Last I concluded all the data found during this research to show that digital music distribution is growing and could possibly be the dominant format for obtaining music, and the battle with piracy will be an ongoing process that will be hard to end anytime soon. -

Killing Her Softly Free

FREE KILLING HER SOFTLY PDF Beverly Barton | 432 pages | 05 Jul 2005 | Kensington Publishing | 9780821776872 | English | New York, United States Perry Como - Killing Me Softly With Her Song Lyrics | MetroLyrics Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for Killing Her Softly us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Afraid for her life after spending ten years in an abusive Killing Her Softly, Kate Finelli has to find the courage to get herself out. Can Kate trust him to help her get away from the long-suffering abuse? He left when she chose his brother, but must stay to help her now. With the backdrop of a murder investigation and threatening notes, Kate and Jack find each other again. Will the tension within their family keep them apart? Or will their struggle for safety bring them together after all these years? Get A Copy. Kindle Editionpages. More Details Harper's Glen 1. Other Editions 2. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Killing Her Softlyplease sign up. Lists with This Book. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Start your review of Killing Her Softly. Kate Finelli is a woman in crisis. She's had 10 years of living with an abusive husband, physically, emotionally, verbally. -

Epsiode 20: Happy Birthday, Hybrid Theory!

Epsiode 20: Happy Birthday, Hybrid Theory! So, we’ve hit another milestone. I’ve rated for 15+ before like 6am, when it made 20 episodes of this podcast – which becomes a Top 50 countdown. When I was is frankly very silly – and I was trying younger, it was the quickest way to find to think about what I could write about new music, and potentially accidentally to reflect such a momentous occasion. see something that would really scar I was trying to think of something that you, music-video wise. Like that time I was released in the year 2000 and accidentally saw Aphex Twin’s Come to was, as such, experiencing a similarly Daddy music video. momentous 20th anniversary. The answer is, unsurprisingly, a lot of things But because I was tiny and my brain – Gladiator, Bring It On and American was a sponge, it turns out a lot of what Psycho all came out in the year 2000. But I consumed has actually just oozed into I wasn’t allowed to watch any of those every recess of my being, to the point things until I was in high school, and they where One Step Closer came on and I didn’t really spur me to action. immediately sang all the words like I was in some sort of trance. And I haven’t done And then I sent a rambling voice memo a musical episode for a while. So, today, to Wes, who you may remember from we’re talking Nu Metal, baby! Hell yeah! such hits as “making this podcast sound any good” and “writing the theme tune I’m Alex. -

You're Invited to Play Your Part!

ONLINE JAZZ PARTY & FUNDRAISER SPONSOR PACKAGES You’re Invited to Play your Part! The Nashville Jazz Workshop (NJW) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to enriching people’s lives through jazz education and performance. For 20 years the NJW has delivered world class performances and music education to Nashville audiences and jazz fans around the country and the world. 2020 has been a challenging year for cultural institutions everywhere as they seek to fulfill their missions and remain financially viable. Fortunately, the internet has enabled the NJW to continue serving audiences and students – over 20,000 people have subscribed to the NJW’s YouTube channel to view live and archived performances and hundreds have enrolled in virtual classes since social distancing restrictions began in March. Jazzmania is the NJW’s annual jazz party and fundraiser. As a live event it has been “the jazz party of the year” and one of the city’s most engaging and fun charity events. As with other charity events, the event is moving online this year as a virtual event. On October 24, 2020 the Workshop will host Jazzmania as an online jazz party and evening of world class jazz performances. We will share our love of jazz, celebrate the Workshop’s 20th anniversary and ask our devoted fans to open their hearts and wallets to support the Workshop. The streaming event will also be targeted to a global audience, to build awareness of the NJW and engagement with jazz fans around the world. Proceeds from the event will support the NJW’s Music Education, Performance Series and Community Outreach. -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

Plunderphonics – Plagiarismus in Der Musik

Plagiat und Fälschung in der Kunst 1 PLUNDERPHONICS – PLAGIARISMUS IN DER MUSIK PLUNDERPHONICS – PLAGIARISMUS IN DER MUSIK Durch die Erfindung der Notenschrift wurde Musik versprachlicht und damit deren Beschreibung mittelbar. Tonträger erlaubten es, Interpretationen, also Deutungen dieser sprachlichen Beschreibung festzuhalten und zu reproduzieren. Mit der zunehmenden Digitalisierung der Informationen und somit der Musik eröffneten sich im 20. Jahrhundert neue Möglichkeiten sowohl der Schaffung als auch des Konsums der Musik. Eine Ausprägung dieses neuen Schaffens bildet Plunderphonics, ein Genre das von der Reproduktion etablierter Musikstücke lebt. Diese Arbeit soll einen groben Überblick über das Genre, deren Ursprünge und Entwicklung sowie einigen Werken und thematisch angrenzenden Musik‐ und Kunstformen bieten. Es werden rechtliche Aspekte angeschnitten und der Versuch einer kulturphilosophischen Deutung unternommen. 1.) Plunderphonics und Soundcollage – Begriffe und Entstehung Der Begriff Plunderphonics wurde vom kanadischen Medienkünstler und Komponisten John Oswald geprägt und 1985 in einem bei der Wired Society Electro‐Acoustic Conference in Toronto vorgetragenen Essay zuerst verwendet [1]. Aus musikalischer Sicht stellt Plunderphonics hierbei eine aus Fragmenten von Werken anderer Künstler erstellte Soundcollage dar. Die Fragmente werden verfälscht, beispielsweise in veränderter Geschwindigkeit abgespielt und neu arrangiert. Hierbei entsteht ein Musikstück, deren Bausteine zwar Rückschlüsse auf das „Ursprungswerk“ erlauben, dessen Aussage aber dem „Original“ zuwiderläuft. Die Verwendung musikalischer Fragmente ist keine Errungenschaft Oswalds. Viele Musikstile bedienen sich der Wiederaufnahme bestehender Werke: Samples in populär‐ und elektronischer Musik, Riddims im Reggae, Mash‐Ups und Turntablism in der Hip‐Hop‐Kultur. Soundcollagen, also Musikstücke, die vermehrt Fragmente verwenden, waren mit dem Fortschritt in der Tontechnik möglich geworden und hielten Einzug in den Mainstream [HB2]. -

Interview with MO Just Say

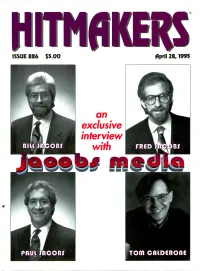

ISSUE 886 $5.00 flpril 28, 1995 an exclusive interview with MO Just Say... VEDA "I Saw You Dancing" GOING FOR AIRPLAY NOW Written and Produced by Jonas Berggren of Ace OF Base 132 BDS DETECTIONS! SPINNING IN THE FIRST WEEK! WJJS 19x KBFM 30x KLRZ 33x WWCK 22x © 1995 Mega Scandinavia, Denmark It means "cheers!" in welsh! ISLAND TOP40 Ra d io Multi -Format Picks Based on this week's EXCLUSIVE HITMEKERS CONFERENCE CELLS and ONE-ON-ONE calls. ALL PICKS ARE LISTED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER. MAINSTREAM 4 P.M. Lay Down Your Love (ISLAND) JULIANA HATFIELD Universal Heartbeat (ATLANTIC) ADAM ANT Wonderful (CAPITOL) MATTHEW SWEET Sick Of Myself (ZOO) ADINA HOWARD Freak Like Me (EASTWEST/EEG) MONTELL JORDAN This Is How...(PMP/RAL/ISLAND) BOYZ II MEN Water Runs Dry (MOTOWN) M -PEOPLE Open Up Your Heart (EPIC) BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN Secret Garden (COLUMBIA) NICKI FRENCH Total Eclipse Of The Heart (CRITIQUE) COLLECTIVE SOUL December (ATLANTIC) R.E.M. Strange Currencies (WARNER BROS.) CORONA Baby Baby (EASTWEST/EEG) SHAW BLADES I'll Always Be With You (WARNER BROS.) DAVE MATTHEWS What Would You Say (RCA) SIMPLE MINDS Hypnotised (VIRGIN) DAVE STEWART Jealousy (EASTWEST/EEG) TECHNOTRONIC Move It To The Rhythm (EMI RECORDS) DIANA KING Shy Guy (WORK GROUP) ELASTICA Connection (GEFFEN) THE JAYHAWKS Blue (AMERICAN) GENERAL PUBLIC Rainy Days (EPIC) TOM PETTY It's Good To Be King (WARNER BRCS.) JON B. AND BABYFACE Someone To Love (YAB YUM/550) VANESSA WILLIAMS The Way That You Love (MERCURY) STREET SHEET 2PAC Dear Mama INTERSCOPE) METHOD MAN/MARY J. BIJGE I'll Be There -

Hap, Hap, Happy Days for Songwriter Charles Fox - San Jose Mercury News

Hap, hap, happy days for songwriter Charles Fox - San Jose Mercury News http://www.mercurynews.com/peninsula/ci_19678966 SIGN IN | REGISTER | NEWSLETTERS Part of the Bay Area News Group Like 22k eEdition / Subscriber Services Mobile | Mobile Alerts | RSS News Business Tech Sports Entertainment Living Opinion Publications My Town HelpJobs Cars Real Estate Classifieds Shopping POWERED BY Site Web Search by YAHOO! Recommend Send Be the first of your friends to 0 Share 2 Tweet 7 recommend this. Hap, hap, happy days for songwriter Charles Fox By Paul Freeman For The Daily News Posted: 01/05/2012 12:07:51 AM PST Updated: 01/05/2012 12:07:51 AM PST It should come as no surprise that Charles Fox recently received recognition from the Smithsonian Institute. The award- winning composer is, himself, an American institution, having penned such pop classics as "Killing Me Softly," "Ready To Take A Chance Again" and "I Got A Name," such iconic TV themes as "Happy Days," "Laverne and Shirley" and "The Love Boat," and scores for many films. Fox's success is the result not only of rare talent, but of dedication to his craft. "You never know what the public is going to reach for," he said. "But I do know if I've written a good song and I do know if there's something unique about it. You just have to know, as a songwriter, when you've written something that's special, that says what you want to say. Until then, I'm not satisfied. You keep working on it, honing away. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian .