Displacement and Protest Movements-The Indian Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 VI June 2017

5 VI June 2017 www.ijraset.com Volume 5 Issue VI, June 2017 IC Value: 45.98 ISSN: 2321-9653 International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology (IJRASET) Elephant Habitat Suitability using Geoinformatics for Palamau Tiger Reserve, Jharkhand (India) Shruti Kanga1, A.C. Pandey2, Ayesha Shaheen3, Suraj Kumar Singh4 1Centre for Climate Change and Water Research, Suresh Gyan Vihar University, Jaipur, India 2,3Centre for Land Resource Management, Central University of Jharkhand, Ranchi, India 4Department of Civil Engineering, Suresh Gyan Vihar University, Jaipur, India Abstract: Geoinformatics plays an important role to understand human wildlife conflicts and the conservation of various natural resources. There have been increase in the incidents of human animal conflicts due to human encroachments in the forest areas and habitat degradation. The objective of the study is to analyze the habitat suitability factors i.e. Forest type, drainage, slope, aspect, contour and elevation were analyzed. The utilization of RS and GIS advances in untamed life mapping, characteristic asset arranging and administration especially in creating nations, is as yet constrained by absence of fitting size of information, equipment, programming and skill. The utilization of GIS to systematize, institutionalize and deal with the huge measures of spatial information produced by the development of elephant out of sight of unsettling influence to the scene. Continuous natural surroundings utilize data by elephant alongside the spatial appropriation of environment and fleeting changes has been broke down for territory assessment. Impediments of customary techniques for physical overview have been evaded by utilizing remote detecting and GIS innovation. By utilizing GIS for coordination and investigation of natural components related with elephants. -

Flood Management Strategy for Ganga Basin Through Storage

Flood Management Strategy for Ganga Basin through Storage by N. K. Mathur, N. N. Rai, P. N. Singh Central Water Commission Introduction The Ganga River basin covers the eleven States of India comprising Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, West Bengal, Haryana, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh and Delhi. The occurrence of floods in one part or the other in Ganga River basin is an annual feature during the monsoon period. About 24.2 million hectare flood prone area Present study has been carried out to understand the flood peak formation phenomenon in river Ganga and to estimate the flood storage requirements in the Ganga basin The annual flood peak data of river Ganga and its tributaries at different G&D sites of Central Water Commission has been utilised to identify the contribution of different rivers for flood peak formations in main stem of river Ganga. Drainage area map of river Ganga Important tributaries of River Ganga Southern tributaries Yamuna (347703 sq.km just before Sangam at Allahabad) Chambal (141948 sq.km), Betwa (43770 sq.km), Ken (28706 sq.km), Sind (27930 sq.km), Gambhir (25685 sq.km) Tauns (17523 sq.km) Sone (67330 sq.km) Northern Tributaries Ghaghra (132114 sq.km) Gandak (41554 sq.km) Kosi (92538 sq.km including Bagmati) Total drainage area at Farakka – 931000 sq.km Total drainage area at Patna - 725000 sq.km Total drainage area of Himalayan Ganga and Ramganga just before Sangam– 93989 sq.km River Slope between Patna and Farakka about 1:20,000 Rainfall patten in Ganga basin -

19 JUNE, 2021 FSR No.19 Dated: 19-06-2021

Central Water Commission Upper Ganga Basin Organisation, Lucknow Daily Flood Situation Report Cum Advisories Date: 19 JUNE, 2021 FSR No.19 Dated: 19-06-2021 1. Weather forecast by IMD I. SYNOPTIC SITUATION: ♦ Southwest monsoon has further advanced into remaining parts of north Arabian Sea, Saurashtra, Gujarat region & Madhya Pradesh, entire Kutch, some more parts of Rajasthan and west Uttar Pradesh today, the 19th June 2021. ♦ The northern Limit of southwest monsoon (NLM) now passes through Lat. 26°N / Long. 70°E, Barmer, Bhilwara, Dholpur, Aligarh, Meerut, Ambala and Amritsar as on today, the 19th June 2021. ♦ Further advance of southwest monsoon into remaining parts of Rajasthan, west Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Chandigarh & Delhi and Punjab is likely to be slow as large scale features are not favourable and the forecast wind pattern by the numerical models do not indicate any favourable condition for sustained rainfall over the region during the forecast period. ♦ The Low pressure area over southeast Uttar Pradesh & neighbourhood with the associated cyclonic circulation extending upto mid tropospheric levels persists. ♦ The trough from West Rajasthan to northeast Bay of Bengal across south Haryana, center of low pressure area over southeast Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Gangetic West Bengal extending upto 0.9 km above mean sea level persists. ♦ The Western Disturbance as a trough in mid & upper tropospheric westerlies with its axis at 5.8 km above mean sea level roughly along Long. 72°E to the north of Lat. 25°N persists. ♦ The cyclonic circulation over south Pakistan & neighbourhood now lies over southwest Rajasthan & neighbourhood between 1.5 km & 7.6 km above mean sea level tilting southwestwards with height. -

6Th International Folk Music Film Festival Catalogue 2016

6th International Folk Music Film Festival 24th - 26th November 2016 'Music f or Life, Music f or Survival' Coordinator:- Ram Prasad Kadel Founder, Music Museum of Nepal. Secretary:- Homenath Bhandari, Nepal International Organising Committee Ananda Das Baul, Musician and filmmaker, India. Anne Houssay, "musical instrument conservator, and research historian, at Laboratoire de recherche et de restauration du musée de la musique, Cité de la musique, Paris, France. Anne Murstad, Ethnomusicologist, singer and musician, University of Agder, Norway. Basanta Thapa, Coordinator, Kathmandu International Mountain Film Festival, (Kimff) Nepal. Charan Pradhan, Dance therapist and traditional Nepalese dancer, Scotland, UK. Claudio Perucchini, Folk song researcher Daya Ram Thapa, PABSON Nepal, Homnath Bhandari, Music Museum of Nepal. K. P. Pathaka, Film Director, Maker, Nepal Krishna Kandel, Folk Singer Mandana Cont, Architect and Poet, Iran. Meghnath, Alternative Filmmaker, Activist and teacher of filmmaking, India. Mohan Karki , Principal, Bright Future English School, Kathmandu Narayan Rayamajhi, Filmmaker and Musician, Nepal. Norma Blackstock, Music Museum of Nepal, Wales, UK. Pete Telfer: Documentary Filmmaker, Wales, UK Pirkko Moisala, Professor of Ethnomusicology, University of Helsinki, Finland. Prakash Jung Karki, Director Nepal Television, Nepal Ram Prasad Kadel, Founder, Music Museum of Nepal, Folk Music Researcher, Nepal. Rolf Killius, South Asian music and dance curator and filmmaker, UK. Steev Brown, Musician, Technical Adviser, Wales, -

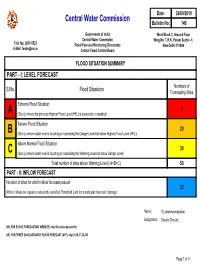

I: LEVEL FORECAST Numbers of S.No

Date: 26/09/2019 Central Water Commission Bulletin No: 149 Government of India West Block 2, Ground Floor Central Water Commision Wing No 7, R.K. Puram Sector -1, Tele fax: 2610 6523 Flood Forecast Monitoring Directorate New Delhi-110066 E-Mail: [email protected] Central Flood Control Room FLOOD SITUATION SUMMARY PART - I: LEVEL FORECAST Numbers of S.No. Flood Situations Forecasting Sites Extreme Flood Situation: 0 A (Site (s) where the previous Highest Flood Level (HFL) is exceeded or equalled) Severe Flood Situation: 20 B (Site (s) where water level is touching or exceeding the Danger Level but below Highest Flood Level (HFL)) Above Normal Flood Situation: 30 C (Site (s) where water level is touching or exceeding the Warning Level but below Danger Level) Total number of sites above Warning Level ( A+B+C) 50 PART - II: INFLOW FORECAST Number of sites for which inflow forecasts issued: 33 (Where Inflows are equal or exceed the specified Threshold Limit for a particular reservoir / barrage) Name: S Lakshminarayanan Designation: Deputy Director URL FOR FLOOD FORECASTING WEBSITE: http://ffs.tamcnhp.com/ffs/ URL FOR THREE DAYS ADVISORY FLOOD FORECAST (AFF): http://120.57.32.251 Page 1 of 11 Central Water Commission Date :26/09/2019 PART-I: DAILY WATER LEVELS AND FORECASTS FOR LEVEL FORECAST SITES A: Extreme Flood Situations : Sites where the previous Highest Flood Level (HFL) is equalled or exceeded Highest Actual level Forecasted Level flood ------------------ -------------------- River District Warning Level (m) Trend Trend Danger --------------------------------------- -

Influence of a Chemical Industry Effluent on Water Quality of Gobindballabh Pant Sagar – a Long Term Study

International Journal of Engineering Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 6734, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 6726 www.ijesi.org ǁ Volume 3 ǁ Issue 1 ǁ January 2014 ǁ PP.07-13 Influence of a Chemical Industry Effluent on Water Quality of GobindBallabh Pant Sagar – A Long Term Study Kachhal Prabhakar1, Beena Anand2, SN Sharma3, Pankaj Sharma4, SL Gupta5 1-5(Central Soil & Materials Research Station, Ministry of Water Resources, New Delhi – 110016 (INDIA) ABSTRACT: GobindBallabh Pant Sagar was created in 1962 on the river Rihand. The Dam is located in the state of Uttar Pradesh (24°12′9″N83°0′29″E 24.2025°N 83.00806°E). It was commissioned for the purposes like irrigation, flood control, fishery and wild life conservation etc. along with electricity generation. Many thermal power plants of different capacity have been raised around the reservoir. Abundance of power promoted establishment of chemical industries. The industrial effluents discharged in the reservoir without proper treatment contaminate the hydro-environment. For the purpose of monitoring the degree of pollution, a long term detailed investigation program was initiated in the region near one of the major industries. The studies aim at monitoring the degree of chemical pollution of reservoir water which will have multifold impacts on both biotic as well as abiotic components. The studies clearly indicate that further deterioration in the quality of the reservoir water has been arrested since monitoring of the quality of reservoir water was initiated. This paper presents the details of the observations carried out in the region around this in different seasons during the period October 2002 to August 2012. -

Water Resource English Cover-2019-20.Cdr

A Panoramic View of Krishna Raja Sagara Dam, Karnataka GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENATION NEW DELHI ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENATION NEW DELHI Content Sl. No. CHAPTER PAGE NO. 1. OVERVIEW 1-14 2. WATER RESOURCES SCENARIO 17-20 3. MAJOR PROGRAMMES 23-64 4. INTER-STATE RIVER ISSUES 67-71 5. INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION 75-81 6. EXTERNAL ASSISTANCE IN WATER RESOURCES SECTOR 85-96 7. ORGANISATIONS AND INSTITUTIONS 99-170 8. PUBLIC SECTOR ENTERPRISES 173-184 9. INITIATIVES IN NORTH EAST 187-194 10. ADMINISTRATION, TRAINING AND GOVERNANACE 197-202 11. TRANSPARENCY 205 12. ROLE OF WOMEN IN WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT 206 13. PROGRESSIVE USE OF HINDI 207-208 14. STAFF WELFARE 211-212 15. VIGILANCE 213 16. APPOINTMENT OF PERSONS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS 214 Annexures Sl. No. ANNEXURES PAGE NO. I. ORGANISATION CHART 217 II. STAFF IN POSITION AS ON 31.12.2019 218 III. LIST OF NAMES & ADDRESSES OF SENIOR OFFICERS & HEADS 219-222 OF ORGANISATIONS UNDER THE DEPARTMENT IV. BUDGET AT GLANCE 223-224 V. 225-226 COMPLETED/ ALMOST COMPLETED LIST OF PRIORITY PROJECTS (AIBP WORKS) REPORTED VI. CENTRAL ASSISTANCE & STATE SHARE DURING RELEASED 227 PMKSY 2016-20 FOR AIBP WORKS FOR 99 PRIORITY PROJECTS UNDER VII. CENTRAL ASSISTANCE & STATE SHARE RELEASED DURING 228 UNDER PMKSY 2016-20 FOR CADWM WORKS FOR 99 PRIORITY PROJECTS VIII. 229 UNDER FMP COMPONENT OF FMBAP STATE/UT-WISE DETAILS OF CENTRAL ASSISTANCE RELEASED IX. -

Scheme N Volume 2) (Transmission Lines Associated with GSS at Chhatarpur

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report (Scheme N Volume 2) (Transmission Lines Public Disclosure Authorized Associated with GSS at Chhatarpur) Jharkhand Urja Sancharan Nigam Limited Final Report January 2019 www.erm.com The Business of Sustainability FINAL REPORT Jharkhand Urja Sancharan Nigam Limited Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report (Scheme N Volume 2) (Transmission Lines Associated with GSS at Chhatarpur) 10 January 2019 Reference # 0402882 Suvankar Das Consultant Prepared by Abhishek Roy Goswami Senior Consultant Reviewed & Debanjan Approved by: Bandyapodhyay Partner This report has been prepared by ERM India Private Limited a member of Environmental Resources Management Group of companies, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 PROJECT OVERVIEW 1 1.3 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THIS ESIA 2 1.4 STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT 2 1.5 LIMITATION -

Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in Figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011

37 Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011 FAO WATER Irrigation in Southern REPORTS and Eastern Asia in figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011 37 Edited by Karen FRENKEN FAO Land and Water Division FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2012 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107282-0 All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. -

Syllabus Analysis

GEOGRAPHY (Syllabus Analysis) DIGMANI EDUCATIONS A-18, Top Floor, Young Chamber Behind, Batra Cinema, Dr. Mukherjee Nagar, Delhi-110009 Mob : 9891290953, 931195007/08/09 ALOK RANJAN’S IAS DIGMANI EDUCATIONS Previous Year Questionaire Paper- I Explain the scientifically sound methods of 1.Geomorphology : Factors controlling bathymetry and give an account of the bottom landform development; endogenetic and exogenetic topography of the Atlantic Ocean. (30M) forces; Origin and evolution of the earth’s crust; Fundamentals of geomagnetism; Physical conditions of 2009 Highlight the geomorphic features essentially the earth’s Interior; Geosynclines; Continental drift; found in topographies under the second cycle Isostasy; Plate tectonics; Recent views on mountain of erosion.(20M) building; Vulcanicity; Earthquakes and Tsunamis; Discuss views on slope development provided Concepts of geomorphic cycles and Landscape by L.C.King.(20M) development; Denudation chronology, Channel 2008 Critically examine the concept of Geomorphic morphology; Erosion surfaces; Slope development; Cycle and discuss the view of W.M. Davis and Applied Geomorphology : Geohydrology, economic W. Penck. geology and environment. 2007 Define the concept of isostasy and discuss the Long Questions postulations of Airy and Pratt. 2018 Evaluate how far Kober’s geosynclinal theory 2006 Critically evaluate the continental drift explains the mountain building process. hypothesis of A. Wegener. 2017 “The knowledge of slope analysis has limited 2005 “Structure is a dominant control factor in the field application in the slope management.” evolution of landform.” Discuss with suitable Explain. examples. 2017 “The knowledge of slope analysis has limited 2004 Describe the landforms which are products of endogenetic forces. field application in the slope management.” Explain. -

GOVERNMENT of INDIA MINISTRY of ENVIRONMENT, FOREST and CLIMATE CHANGE INDIRA PARYAVARAN BHAVAN, JOR BAHG ROAD JOR BAGH, NEW DELHI 110 003 1 | P a G E

st 51 MEETING OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE OF NATIONAL BOARD FOR WILDLIFE 14th NOVEMBER 2018 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE INDIRA PARYAVARAN BHAVAN, JOR BAHG ROAD JOR BAGH, NEW DELHI 110 003 1 | P a g e INDEX S.No. AGENDA ITEMS Pg No. 1 AGENDA No. 1 Confirmation of the Minutes of 50th Meeting of the Standing Committee of National Board for 3-10 Wildlife was held on 7th September 2018 2 AGENDA No. 2 Action Taken Report on the recommendations 50th Meeting of the Standing Committee of 12 National Board for Wildlife was held on 7th September 2018 3 AGENDA No. 3 13 - 37 Jharkhand 13-18 Rajasthan 19-21 Uttarakhand 22-37 4 AGENDA No. 4 Any other item with the permission of the Chair 38 ANNEXURES Minutes of 50th Meeting of the Standing Committee of National Board for Wildlife was held 39 – 70 on 7th September 2018 Fact Sheets 71 2 | P a g e st AGENDA FOR 51 MEETING OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE OF NAT IONAL BOARD FOR WILDLIFE AGENDA No. 1 51.1. Confirmation of the minutes of 50th Meeting of the Standing Committee of National Board for Wildlife was held on 7th September 2018 The minutes of 50th Meeting of the Standing Committee of National Board for Wildlife was held on 7th September 2018. Copy of the minutes is placed at ANNEXURE 51.1. However suggestions / representations have been received on the following proposals: 50.3.6.1 Re-notifying the boundaries of Shettihalli Wildlife Sanctuary without reducing the area and extent (Fact Sheet ANNEXURE 51.2) The Standing Committee of NBWL in its 50th meeting held on 7th September 2018 has recommended the proposal for the re-notification / rationalization of Shettihalli Wildlife Sanctuary with an area of 395.608 sq.km excluding ~300 sq.km from the inadvertent area of 695.608 sq.km. -

Rivers of India

Downloaded From examtrix.com Compilation of Rivers www.onlyias.in Mahanadi RiverDownloaded From examtrix.com Source: Danadkarnya Left bank: Sheonath, Hasdo and Mand Right bank: Tel, Jonk, Ong Hirakund dam Olive Ridley Turtles: Gahirmatha beach, Orissa: Nesting turtles River flows through the states of Chhattisgarh and Odisha. River Ends in Bay of Bengal Mahanadi RiverDownloaded From examtrix.com Mahanadi RiverDownloaded From examtrix.com • The Mahanadi basin extends over states of Chhattisgarh and Odisha and comparatively smaller portions of Jharkhand, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, draining an area of 1.4 lakh Sq.km. • It is bounded by the Central India hills on the north, by the Eastern Ghats on the south and east and by the Maikala range on the west. • The Mahanadi (“Great River”) follows a total course of 560 miles (900 km). • It has its source in the northern foothills of Dandakaranya in Raipur District of Chhattisgarh at an elevation of 442 m. • The Mahanadi is one of the major rivers of the peninsular rivers, in water potential and flood producing capacity, it ranks second to the Godavari. Mahanadi RiverDownloaded From examtrix.com • Other small streams between the Mahanadi and the Rushikulya draining directly into the Chilka Lake also forms the part of the basin. • After receiving the Seonath River, it turns east and enters Odisha state. • At Sambalpur the Hirakud Dam (one of the largest dams in India) on the river has formed a man-made lake 35 miles (55 km) long. • It enters the Odisha plains near Cuttack and enters the Bay of Bengal at False Point by several channels.