Artist Statement by Nels Cline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amjad Ali Khan & Sharon Isbin

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

Riis's How the Other Half Lives

How the Other Half Lives http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/title.html HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVES The Hypertext Edition STUDIES AMONG THE TENEMENTS OF NEW YORK BY JACOB A. RIIS WITH ILLUSTRATIONS CHIEFLY FROM PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN BY THE AUTHOR Contents NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1890 1 of 1 1/18/06 6:25 AM Contents http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/contents.html HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVES CONTENTS. About the Hypertext Edition XII. The Bohemians--Tenement-House Cigarmaking Title Page XIII. The Color Line in New York Preface XIV. The Common Herd List of Illustrations XV. The Problem of the Children Introduction XVI. Waifs of the City's Slums I. Genesis of the Tenements XVII. The Street Arab II. The Awakening XVIII. The Reign of Rum III. The Mixed Crowd XIX. The Harvest of Tare IV. The Down Town Back-Alleys XX. The Working Girls of New York V. The Italian in New York XXI. Pauperism in the Tenements VI. The Bend XXII. The Wrecks and the Waste VII. A Raid on the Stale-Beer Dives XXIII. The Man with the Knife VIII.The Cheap Lodging-Houses XXIV. What Has Been Done IX. Chinatown XXV. How the Case Stands X. Jewtown Appendix XI. The Sweaters of Jewtown 1 of 1 1/18/06 6:25 AM List of Illustrations http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/illustrations.html LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. Gotham Court A Black-and-Tan Dive in "Africa" Hell's Kitchen and Sebastopol The Open Door Tenement of 1863, for Twelve Families on Each Flat Bird's Eye View of an East Side Tenement Block Tenement of the Old Style. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

SA-Bio-4.2017.Pdf

Scott Amendola: Drummer/Composer/Bandleader/Educator “Amendola’s music is consistently engaging, both emotionally and intellectually, the product of a fertile and inventive musical imagination.” Los Angeles Times “If Scott Amendola didn't exist, the San Francisco music scene would have to invent him.” Derk Richardson, San Francisco Bay Guardian “Amendola has complete mastery of every piece of his drumset and the ability to create a plethora of sounds using sticks, brushes, mallets, and even his hands.”Steven Raphael, Modern Drummer “...drummer/signal-treater Scott Amendola is both a tyrant of heavy rhythm and an electric-haired antenna for outworldly messages (not a standard combination).” Greg Burk, LA Weekly For Scott Amendola, the drum kit isn’t so much an instrument as a musical portal. As an ambitious composer, savvy bandleader, electronics explorer, first-call accompanist and capaciously creative foil for some of the world’s most inventive musicians, Amendola applies his wide-ranging rhythmic virtuosity to a vast array of settings. His closest musical associates include guitarists Nels Cline, Jeff Parker, Charlie Hunter, Hammond B-3 organist Wil Blades, violinists Jenny Scheinman and Regina Carter, saxophonists Larry Ochs and Phillip Greenlief, and clarinetist Ben Goldberg, players who have each forged a singular path within and beyond the realm of jazz. While rooted in the San Francisco Bay Area scene, Amendola has woven a dense and far-reaching web of bandstand relationships that tie him to influential artists in jazz, blues, rock and new music. A potent creative catalyst, the Berkeley-based drummer is the nexus for a disparate community of musicians stretching from Los Angeles and Seattle to Chicago and New York. -

“The First Thing You Notice About David Breskin Is That He's Got Chops up The

“The first thing you notice about David Breskin is that he’s got chops up the wazoo and is fabulously intelligent. It may take longer to start seeing through his fierce and faceted eye or to notice how many of our lived-in worlds it sees in all their dazzle of simultaneity and fact. This is poetry in which the intimate and public worlds do not exclude each other but mutually refract their signs and lights, and where even the self on which the world imposes its unrelenting politics can earn, with ingenuity and effort, its meed of radiance.” —Rafi Zabor, author of The Bear Comes Home, PEN/Faulkner Award Winner “In David Breskin’s Escape Velocity, ferocity and speed don’t preclude clarity of critique, and the tectonic instabilities of metaphor’s capacity for disruption is married to a clarity of focus, producing a vivid, Baroque pageantry that defies chronology in favor of synchronicity, that gives us panoramas of wrecks. Rare to find poetry that is so confrontational, so avid to go to the hot spots, to risk being brutal in the service of truth while preserving such formal elegance. Unflinching, these poems roar like Cassandra with disastrous moment: it’s a transfixing sound.” —Dean Young, author of Skid “David Breskin’s Escape Velocity is torqued with rage at the world as he finds it, ‘a micro avalanche of each soul’s presence.’ With formal precison and clarity, he elucidates the sorrows of our times, an unflinching and brave indictment of the spoils of life’s wars, both personal and political. -

Neg(Oti)Ating Fusion: Steely Dan's Generic Irony by Ethan Krajewski A

Neg(oti)ating Fusion: Steely Dan’s Generic Irony by Ethan Krajewski A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2018 © 2018 Ethan Patrick Krajewski To my parents for music and language Acknowledgements My biggest thanks go to my advisor, Professor Julian Levinson, as a teacher, mentor, and friend, for helping me think, talk, write, and (most importantly, I think) laugh about seventies rock music. You’ve helped make this project fun in all of its rigor and relaxed despite all of the stress that it’s caused. I’d also like to thank Professor Gillian White for leading our cohort toward discipline, and for keeping us all grounded. Also for her spirited conversations and anecdotes, which proved invaluable in the early stages of my thinking. I wouldn’t be here writing this if it weren’t for Professor Supriya Nair, who pushed me to apply for the program and helped me develop the intellectual curiosity that led to this project. The same goes for Gina Brandolino, who I count among my most important teachers and role models. To the cohort: thank you for all of your help over the course of the year. You’re all so smart, and so kind, and I wish you all nothing but the best. To Ashley: if you aren’t the best non-professional line editor at large in the world, then you’re at least second or third. I mean it sincerely when I say that this project would be infinitely worse without your guidance. -

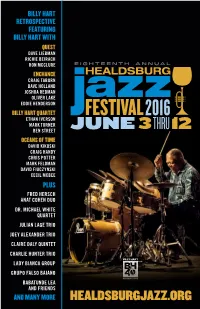

Billy Hart Retrospective Featuring Billy Hart with Plus and Many More

BILLY HART RETROSPECTIVE FEATURING BILLY HART WITH QUEST DAVE LIEBMAN RICHIE BEIRACH RON MCCLURE ENCHANCE CRAIG TABORN DAVE HOLLAND JOSHUA REDMAN OLIVER LAKE EDDIE HENDERSON BILLY HART QUARTET ETHAN IVERSON MARK TURNER BEN STREET OCEANS OF TIME DAVID KIKOSKI CRAIG HANDY CHRIS POTTER MARK FELDMAN DAVID FIUCZYNSKI CECIL MCBEE PLUS FRED HERSCH ANAT COHEN DUO DR. MICHAEL WHITE QUARTET JULIAN LAGE TRIO JOEY ALEXANDER TRIO CLAIRE DALY QUINTET CHARLIE HUNTER TRIO LADY BIANCA GROUP GRUPO FALSO BAIANO BABATUNDE LEA AND FRIENDS AND MANY MORE So many great jazz masters have had tributes to their talent and contributions, I felt one for Billy was way overdue. He is truly one of the greatest drummers in jazz history. He has been on thousands of recordings over his 50-year career and, in turn, has enhanced the careers of several exceptional musicians. He has also been a true friend to Healdsburg Jazz Festival, performing here 11 out of the past 17 years. Many people do not know his deep contributions to jazz and the vast number of musicians he has performed and recorded with over the years as leader, sideman and collaborator: Shirley Horn, Wes Montgomery, Betty Carter, Jimmy Smith, McCoy Tyner, Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Stan Getz, and so many more (see the Billy Hart discography on our website). When he began to lead his own bands in 1977, they proved to be both disciplined and daring. For this tribute, we will take you through his musical history, and showcase his deep passion for jazz and the breadth of his achievements. -

We Offer Thanks to the Artists Who've Played the Nighttown Stage

www.nighttowncleveland.com Brendan Ring, Proprietor Jim Wadsworth, JWP Productions, Music Director We offer thanks to the artists who’ve played the Nighttown stage. Aaron Diehl Alex Ligertwood Amina Figarova Anne E. DeChant Aaron Goldberg Alex Skolnick Anat Cohen Annie Raines Aaron Kleinstub Alexis Cole Andrea Beaton Annie Sellick Aaron Weinstein Ali Ryerson Andrea Capozzoli Anthony Molinaro Abalone Dots Alisdair Fraser Andreas Kapsalis Antoine Dunn Abe LaMarca Ahmad Jamal ! Basia ! Benny Golson ! Bob James ! Brooker T. Jones Archie McElrath Brian Auger ! Count Basie Orchestra ! Dick Cavett ! Dick Gregory Adam Makowicz Arnold Lee Esperanza Spaulding ! Hugh Masekela ! Jane Monheit ! J.D. Souther Adam Niewood Jean Luc Ponty ! Jimmy Smith ! Joe Sample ! Joao Donato Arnold McCuller Manhattan TransFer ! Maynard Ferguson ! McCoy Tyner Adrian Legg Mort Sahl ! Peter Yarrow ! Stanley Clarke ! Stevie Wonder Arto Jarvela/Kaivama Toots Thielemans Adrienne Hindmarsh Arturo O’Farrill YellowJackets ! Tommy Tune ! Wynton Marsalis ! Afro Rican Ensemble Allan Harris The Manhattan TransFerAndy Brown Astral Project Ahmad Jamal Allan Vache Andy Frasco Audrey Ryan Airto Moreira Almeda Trio Andy Hunter Avashai Cohen Alash Ensemble Alon Yavnai Andy Narell Avery Sharpe Albare Altan Ann Hampton Callaway Bad Plus Alex Bevan Alvin Frazier Ann Rabson Baldwin Wallace Musical Theater Department Alex Bugnon Amanda Martinez Anne Cochran Balkan Strings Banu Gibson Bob James Buzz Cronquist Christian Howes Barb Jungr Bob Reynolds BW Beatles Christian Scott Barbara Barrett Bobby Broom CaliFornia Guitar Trio Christine Lavin Barbara Knight Bobby Caldwell Carl Cafagna Chuchito Valdes Barbara Rosene Bobby Few Carmen Castaldi Chucho Valdes Baron Browne Bobby Floyd Carol Sudhalter Chuck Loeb Basia Bobby Sanabria Carol Welsman Chuck Redd Battlefield Band Circa 1939 Benny Golson Claudia Acuna Benny Green Claudia Hommel Benny Sharoni Clay Ross Beppe Gambetta Cleveland Hts. -

Uptown Conversation : the New Jazz Studies / Edited by Robert G

uptown conversation uptown conver columbia university press new york the new jazz studies sation edited by robert g. o’meally, brent hayes edwards, and farah jasmine griffin Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © 2004 Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Uptown conversation : the new jazz studies / edited by Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-231-12350-7 — ISBN 0-231-12351-5 1. Jazz—History and criticism. I. O’Meally, Robert G., 1948– II. Edwards, Brent Hayes. III. Griffin, Farah Jasmine. ML3507.U68 2004 781.65′09—dc22 2003067480 Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 contents Acknowledgments ix Introductory Notes 1 Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin part 1 Songs of the Unsung: The Darby Hicks History of Jazz 9 George Lipsitz “All the Things You Could Be by Now”: Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus and the Limits of Avant-Garde Jazz 27 Salim Washington Experimental Music in Black and White: The AACM in New York, 1970–1985 50 George Lewis When Malindy Sings: A Meditation on Black Women’s Vocality 102 Farah Jasmine Griffin Hipsters, Bluebloods, Rebels, and Hooligans: The Cultural Politics of the Newport Jazz Festival, 1954–1960 126 John Gennari Mainstreaming Monk: The Ellington Album 150 Mark Tucker The Man 166 John Szwed part 2 The Real Ambassadors 189 Penny M. -

Who Cycles Into Our Valley

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English Spring 5-10-2012 Who Cycles Into Our Valley Benjamin M. Solomon Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Recommended Citation Solomon, Benjamin M., "Who Cycles Into Our Valley." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 WHO CYCLES INTO OUR VALLEY STORIES by BENJAMIN SOLOMON Under the direction of Sheri Joseph ABSTRACT The twelve stories in this collection chart a course between the United States and India. Some are set wholly in one country, while others form a bridge between the two. Uniting them is a shared attention to memory, isolation, and loss. In their own idiosyncratic ways, each of the characters in these small fictions is struggling for human connection in a hostile and lonely world. INDEX WORDS: Fiction, India, Isolation, Loss, Short stories 2 WHO CYCLES INTO OUR VALLEY STORIES by BENJAMIN SOLOMON A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in the College of Arts and Sciences Georgia State University 2012 3 Copyright by Benjamin Solomon 2012 4 WHO CYCLES INTO OUR VALLEY STORIES by BENJAMIN SOLOMON Committee Chair: Sheri Joseph Committee: Josh Russell John Holman Electronic Version Approved: Office of Graduate Studies College of Arts and Sciences Georgia State University May 2012 iv Acknowledgements My sincere gratitude to Sheri Joseph, Josh Russell, and John Holman. -

Henry Kaiser-Ray Russell

Bio information: HENRY KAISER & RAY RUSSELL Title: THE CELESTIAL SQUID (Cuneiform Rune 403) Format: CD / DIGITAL Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American & world radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / AVANT-JAZZ / IMPROV Uncaged Session Ace Ray Russell Makes Long-Awaited Return to Guitar's Outer Limits Alongside Experimental Guitarist Henry Kaiser on The Celestial Squid Guitar summits don't ascend higher than when legendary British free-jazz pioneer and longtime session ace Ray Russell meets the brilliant California avant-improv overachiever and Antarctic diver Henry Kaiser in the realm of The Celestial Squid. An album as cosmically evocative as its title, The Celestial Squid marks both a promising new partnership and a return to the outer-limits sensibility that informed Russell's earliest work. With sixteen albums as a leader and more than countless session performances to his credit, including the early James Bond film scores, Russell is returning to his bone-rattling, noise-rocking roots for the first time since 1971. You'll be shaken and stirred as Kaiser, Russell, and eight super friends deliver a no-holds-barred, free-range sonic cage match. They evoke improvised music's past, present, and future while proving that free jazz can still be good, clean, liberating fun. Russell created some of the early '70s' most outrageously outside music. Live at the ICA: June 11th 1971 is a particularly hallmark work of guitar shock-and-awe. Russell's "stabbing, singing notes and psychotic runs up the fretboard have nothing to do with scalular architecture," wrote All Music's Thom Jurek, "but rather with viscera and tonal exploration." Russell anticipated the wildest and most intrepid vibrations of Terje Rypdal, Dave Fuzinski, Sonic Youth, Keiji Haino, Tisziji Muñoz, Alan Licht (who contributes liner notes), and their boundary-dissolving ilk. -

The Ultimate Listening-Retrospect

PRINCE June 7, 1958 — Third Thursday in April The Ultimate Listening-Retrospect 70s 2000s 1. For You (1978) 24. The Rainbow Children (2001) 2. Prince (1979) 25. One Nite Alone... (2002) 26. Xpectation (2003) 80s 27. N.E.W.S. (2003) 3. Dirty Mind (1980) 28. Musicology (2004) 4. Controversy (1981) 29. The Chocolate Invasion (2004) 5. 1999 (1982) 30. The Slaughterhouse (2004) 6. Purple Rain (1984) 31. 3121 (2006) 7. Around the World in a Day (1985) 32. Planet Earth (2007) 8. Parade (1986) 33. Lotusflow3r (2009) 9. Sign o’ the Times (1987) 34. MPLSound (2009) 10. Lovesexy (1988) 11. Batman (1989) 10s 35. 20Ten (2010) I’VE BEEN 90s 36. Plectrumelectrum (2014) REFERRING TO 12. Graffiti Bridge (1990) 37. Art Official Age (2014) P’S SONGS AS: 13. Diamonds and Pearls (1991) 38. HITnRUN, Phase One (2015) ALBUM : SONG 14. (Love Symbol Album) (1992) 39. HITnRUN, Phase Two (2015) P 28:11 15. Come (1994) IS MY SONG OF 16. The Black Album (1994) THE MOMENT: 17. The Gold Experience (1995) “DEAR MR. MAN” 18. Chaos and Disorder (1996) 19. Emancipation (1996) 20. Crystal Ball (1998) 21. The Truth (1998) 22. The Vault: Old Friends 4 Sale (1999) 23. Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic (1999) DONATE TO MUSIC EDUCATION #HonorPRN PRINCE JUNE 7, 1958 — THIRD THURSDAY IN APRIL THE ULTIMATE LISTENING-RETROSPECT 051916-031617 1 1 FOR YOU You’re breakin’ my heart and takin’ me away 1 For You 2. In Love (In love) April 7, 1978 Ever since I met you, baby I’m fallin’ baby, girl, what can I do? I’ve been wantin’ to lay you down I just can’t be without you But it’s so hard to get ytou Baby, when you never come I’m fallin’ in love around I’m fallin’ baby, deeper everyday Every day that you keep it away (In love) It only makes me want it more You’re breakin’ my heart and takin’ Ooh baby, just say the word me away And I’ll be at your door (In love) And I’m fallin’ baby.