OLIVIER WILLEMSEN ROZA Sample Translated by Moshe Gilula in Memory of the Dyatlov Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountain of the Dead: the Dyatlov Pass Incident Ebook

MOUNTAIN OF THE DEAD: THE DYATLOV PASS INCIDENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Keith Mccloskey | 224 pages | 01 Oct 2013 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752491486 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom Mountain of the Dead: The Dyatlov Pass Incident PDF Book I recommend this book for anyone looking into this case. Their goal was to reach mount Otorten literally "don't go there" summit. What drove nine experienced hikers to flee for their lives into the night of bone numbing temperatures by cutting open their own tent from the inside with no signs of an avalanche or attackers? His name would later be given to the area where the tragedy took place, as well as the incident itself. Finally, although early on he points out that Kholat Syakhl means "Dead Mountain" in Mansi a place where nothing lives? Alfred J. What happened that night in February? Want to Read saving…. On the night of February 2, , nine experienced hikers cut open their own tent and fled for their lives, blindly, into a blizzard, half-dressed deep in the Ural Mountains. Andrey Kuryakov told the news conference that investigators were relying on the help of "friends and family of the deceased" as well as modern technology, which was not available at the time. Sort order. Even more perplexing was the fact that the searchers, after inspecting the severely damaged tent, came to the conclusion that the material had been torn from the inside , as if its occupants had been frantic to escape from something that was already sealed in the tent with them or were in such a rush that unclasping the tent from the inside was not an option! Still other such journeys into the unknown end in such unfathomably frightening circumstances that they become the stuff of legend. -

Discovery Channel Heads Deep Into Siberia in Search of Russian Yeti on Sunday, June 1

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: DISCOVERY CHANNEL HEADS DEEP INTO SIBERIA IN SEARCH OF RUSSIAN YETI ON SUNDAY, JUNE 1 American explorer Mike Libecki Investigates Mysterious Deaths of Nine Students and Uncovers Something Truly Horrifying (Los Angeles, Calif.) – On February 2, 1959, nine college students hiked up the icy slopes of the Ural Mountains in the heart of Russia but never made it out alive. Investigators have never been able to give a definitive answer behind who – or what – caused the bizarre crime scene. Fifty-five years later, American explorer Mike Libecki reinvestigates the mystery – known as The Dyatlov Pass incident – but what he uncovers is truly horrifying. RUSSIAN YETI: THE KILLER LIVES, a 2-hour special airing Sunday, June 1 at 9 PM ET/PT on the Discovery Channel, follows Mike as he traces the clues and gathers compelling evidence that suggests the students’ deaths could be the work of a creature thought only to exist in folklore. Based on diary accounts, forensic evidence and files that have just recently been released, Mike pieces together the graphic stories in search of what really happened that evening. According to the investigators at the time, the demise of the group was due to a "compelling natural force." The students’ slashed tent was discovered first with most of their clothing and equipment still inside. Next, the students’ bodies were found scattered across the campsite in three distinct groups, some partially naked and with strange injuries including crushed ribs, a fractured skull, and one hiker mutilated with her eyes gouged out and tongue removed. The mysterious scene left more questions than answers. -

The Welsh Triangle 35 Charles J Hall

A BRAND NEW MAGAZINE ON UFOLOGY & ALTERNATIVE THINKING TOP 10 UFOLOGY MOMENTS Lazar, Arnold & Rendlesham ISSUE #1 NOV/DEC 2017 NICK POPE THE From civil servant to the WELSH MoD’s UFO investigator TO THE STARS TRIANGLE Rockstar Tom Delonge Celebrating the 40th is shaping our future Anniversary of the Pembrokeshire sightings DYATLOV PASS SNOW WHITE The mystery deaths of Does the beloved princess nine Russian hikers in 1959 have Egyptian origins? THE PIRI REIS MAP ENIGMA Could this medieval map really show an ice-free Antarctica? MICHAEL CREMO Why human origins may go back further than we thought S-4 DIGITAL PRESS Plus more great interviews and features inside! EDITOR’S LETTER WELCOME! “Something inside me has always been there… - then I was awake, and I need help.” he above quote was featured feeling your IQ drop in front of the in the trailer for the upcoming television and smartphone watching TStar Wars: The Last Jedi, mind numbing talk shows and the which finds our hero Rey searching endless plague of vacuous ‘reality’ for guidance in helping her make celebrities. And that’s what the sense of her recent ‘awakening’. title itself refers to, the dark hidden The line stuck in our minds as we corners of the subconscious that were compiling this very first issue recognises there is a vast amount of Shadows Of Your Mind magazine, of information hidden just out of and it seemed pretty apt as interest view. Our hope is that Shadows… in what were previously fringe topics will act as the catalyst that fires up is on the rise. -

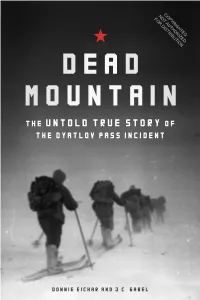

The Untold TRUE Story Of

COPYRIGHTED: NOT FOR AUTHORIZED DISTRIBUTION The Untold TRUE Story o f the Dyatlov Pass Incident Donnie Eichar and J.C. Gabel COPYRIGHTED: NOT FOR AUTHORIZED DISTRIBUTION COPYRIGHTED: NOT FOR AUTHORIZED DISTRIBUTION The Hikers’ Story Рюкзаков, по традиции, легких, Let your backpacks be light, Погоды—хорошей всегда, weather be always fine, Зимой—не слишком морозной, winter be not too cold, А летом —чтоб не жара. and summer without heat GEORGY KRIVONISHCHENKO, excerpt from “New Year’s Poem,” 1959. If one had been able to glimpse inside dormitory 531 on the 23rd of January, 1959, one would have seen the very picture of fellowship, youth and happiness. The room was not particularly attractive or comfortable. The furnishings were serviceable at best, and the room was perpetually drafty, compelling its occupants to wear hats and bulky sweaters indoors for half the year. One might have assumed in observing the room—with its blistered paint, lumpy mattresses and lingering odor of kerosene—that the students who resided in these dormitories must have taken pleasure in things outside material comforts. They must certainly have lived for books, art, friends and nature, interests that could carry them beyond this dingy cupboard. And one would be right. On that third Friday in January, a month 8 COPYRIGHTED: NOT FOR AUTHORIZED DISTRIBUTION before the school term was to begin, the ten friends in 531 were younger sister Tatiana would later attest, his bedroom walls at home engaged in last-minute packing for a trip, one that would take them were plastered with radio panels, homemade receivers, and a short- far away from the confines of college dormitory life, and far beyond wave radio that he would use to communicate with other radio en- their familiar surroundings. -

Authors Russian Fantasy & Science-Fiction Fantasy, Litrpg/Cyberpunk, Postapocalypsis, Romantasy, Space Opera, Young Adult & All Age

Aflatuni, Sukhbat Bochkov, Valery CATALOGUE Burchuladze, Zaza 2017 Danilov, Dmitri Eidman, Igor Grigorenko, Aleksandr Kanovich, Grigori Kochergin, Eduard Lesnyanski, Aleksei Loiko, Sergei Martinovich, Viktor Matveeva, Anna Nikitin, Aleksei Norbekov, Mirzakarim Odnobibl, Mikhail Pavlov, Oleg Rakitin, Aleksei contact Sekisov, Anton Thomas Wiedling Senchin, Roman t | +49-89-62242844 Sharov, Vladimir m | +49-174-2759072 fax | +49-8152-78548 Slapovski, Aleksei [email protected] Slavnikova, Olga wiedling-litag.com Yuzefovich, Leonid fantasy.wiedling-litag.com Zaionchkovski, Oleg news.wiedling-litag.com awards.wiedling-litag.com topseller.wiedling-litag.com Wiedling Literary Agency Pappenheimstrasse 3 80335 Munich, Germany authors Russian Fantasy & Science-Fiction Fantasy, LitRPG/Cyberpunk, Postapocalypsis, Romantasy, Space Opera, Young Adult & All Age Michael Atamanov | Aleksei Bobl | Andrei Levitski | Andrei Livadny | Vasily Mahanenko | H.L. Oldie | Aleksei Osadchuk | Nik Perumov | Dmitri Rus | Vitali Sertakov | Elena Zvezdnaya fantasy.wiedling-litag.com Sukhbat Aflatuni title Poklonenie volkhvov The Adoration of the Magi Novel. Ripol. Moscow 2015. 776 pages The saga of the Triyarski family covers Russian history from the tsars in the middle of the 19th century through the revolution and the red terror to beyond the soviet era. The patriarch of the family, Nikolai, is a progressive architect who associates with enlightened secret societies in St. Petersburg. These are betrayed as being agitators and senten- ced to death. On the 22nd December 1849, they are taken to the scaffold and about to be executed together with Dostoevski, but are surprisingly reprieved at the last second by the Tsar himself. Nikolai is unaware that he has his sister Varvara to thank for the reprieve. -

Using Science to Explore a 60-Year-Old Russian Mystery, the Dyatlov Pass Incident 28 January 2021

Using science to explore a 60-year-old Russian mystery, the Dyatlov Pass incident 28 January 2021 Avalanche Research SLF, had never heard of the case, which the Russian Public Prosecutor's Office had recently resurrected from Soviet-era archives. "I asked the journalist to call me back the following day so that I could gather more information. What I learned intrigued me." A sporting challenge that ended in tragedy On 27 January 1959, a 10-member group consisting mostly of students from the Ural Polytechnic Institute, led by 23-year-old Igor Dyatlov—all seasoned cross-country and downhill skiers—set off on a 14-day expedition to the Gora Otorten mountain, in the northern part of the Soviet Sverdlovsk Oblast. At that time of the year, a route of this kind was classified Category III—the riskiest Configuration of the Dyatlov group's tent installed on a flat surface after making a cut in the slope below a small category—with temperatures falling as low as -30 shoulder. Credit: Gaume/Puzrin degrees C. On January 28, one member of the expedition, Yuri Yudin, decided to turn back. He never saw his classmates again. Researchers from EPFL and ETH Zurich have When the group's expected return date to the conducted an original scientific study that puts departure point at the village of Vizhay came and forth a plausible explanation for the mysterious went, a rescue team set out to search for them. On 1959 death of nine hikers in the Ural Mountains in 26 February, they found the group's tent, badly the former Soviet Union. -

Dyatlov Pass Incident from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Coordinates: 61°45′17″N 59°27′46″E Dyatlov Pass incident From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Dyatlov Pass incident was an event that took the lives of nine hikers in mysterious circumstances on the night of February 2, 1959 in the northern Ural Mountains. The name Dyatlov Pass refers to the name of the group's leader, Igor Dyatlov. The incident involved a group of nine experienced ski hikers from the Ural Polytechnical Institute (Уральский политехнический институт, УПИ) who had set up camp for the night on the slopes of Kholat Syakhl. Investigators later determined that the skiers had torn their tents from the inside out. They fled the campsite, probably to escape an imminent threat. Some of them were barefoot, under heavy snowfall. The bodies showed signs of struggle; Dyatlov had injuries to his right fist, as if he had been in a fist fight. Two victims had fractured skulls and broken ribs. One of the skull fractures was so severe it was determined that he would not have been able to move. Additionally, one woman's tongue Location of Dyatlov Pass, Russia was missing. Soviet authorities determined that an "unknown compelling force" had caused the deaths; access to the region was consequently blocked for hikers and adventurers for three years after the incident. Due to the lack of survivors, the chronology of events remains uncertain, although several possible explanations have been put forward, including an avalanche, a military accident, and a hostile encounter with a yeti or other unknown creature. Contents 1 Background 2 Search and discovery 3 Investigation 3.1 Controversy regarding investigation 4 Aftermath 5 2016 Incident 6 Explanations 6.1 Hypothermia 6.2 Avalanche 6.3 Yeti 6.4 Radford 6.5 Infrasounds 6.6 Military tests 7 In popular culture 8 Further reading 9 References 10 External links Background A group was formed for a ski trek across the northern Urals in Sverdlovsk Oblast. -

The Dyatlov Pass Incident True Crime

true crime The Dyatlov Pass Incident True crime. St. Petersburg 2012. ca. 430 pages including illustrations Publishers: Germany - Random House, Czech Republic - Dobrovsky With an epilogue by Oleg Kashin The Dyatlov Pass incident resulted in the deaths of nine ski hikers in the northern Ural mountains on the night of February 2, 1959. The mountain pass where the incident occurred has since been named Dyatlov Pass after the group‘s leader, Igor Dyatlov. The lack of eyewitnesses has inspired much speculation. Soviet investigators deter- mined only that “a compelling unknown force” had caused the deaths. Access to the area was barred for skiers and other adventurers for three years after the incident. Investigators at the time determined that the hikers tore open their tent from within, departing barefoot into heavy snow and a temperature of −30 °C (−22 °F). Although the corpses showed no signs of struggle, two victims had fractured skulls, two had broken ribs, and one was missing her tongue. Their clothing, when tested, was found to be highly radioactive. THE AUTHOR This book makes a new attempt to analyse all of the information available up until today about the mysterious deaths of the group of Sverdlovsk tourists on the Dyatlov translations Pass in the winter of 1959 and to evaluate them for the first time without any of the 2 languages mystic suppositions that have dogged this unexplained event. In doing so, the author draws on two witnesses still living as well as on archives and on secret files held in Yekaterinburg and elsewhere, files that have been withheld from the public up to samples available now. -

GOVERNMENT INVOLVEMENT in the UFO COVER-UP: CHRONOLOGY (Based on FOIA Papers and Personal Testimony) Version 2

GOVERNMENT INVOLVEMENT IN THE UFO COVER-UP: CHRONOLOGY (Based on FOIA Papers and personal testimony) Version 3.6 COPYRIGHT SEPTEMBER 8, 1988 c. by PEA RESEARCH (updated 11AUG2015). ULTRA MAJIC BBS (no longer in service; 50megs.com no longer updated). Instead go to http://www.iaesr.wordpress.com/ home page. Note: YouTube wasn’t available in 1988, so I’ve added YouTube links available in 2015. (This document; be sure to clear history (CNTRL-H) to see the latest version.) Older v2.09 (no longer updated) Sites that reference PEA Research: The Conspiracy Shack; Societas Montis Solis; Byron Wine; PADRAK; CCO; BeFreeTech; ThinkAboutIt-UFOs; TheAnomaliesChannel This article was partially published 1990 in UFO CRASH SECRETS AT WRIGHT-PATTERSON AFB, p.84. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- DEDICATION TO: LARRY BRYANT He is the crusader in shining armor… Thanks, Larry! without whom much of the Top Secret Declassified documents wouldn’t have been available for this report. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- CLASSIFICATIONS: CE-1 (close visual sighting), CE-2 (physical evidence), CE-3 (Occupants observed), CE-4 (Missing Time), CE-5 (Voluntary direct communication) Alien Bodies Discs .................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Dyatlov Pass Incident 013112.Fdx

THE DYATLOV PASS INCIDENT by Vikram Weet Inspired by True Events WHITE PRODUCTION DRAFT - 01/31/12 Midnight Sun Pictures 73 Market Street Venice, CA 90291 (310) 902-0431 K.JAM Media 2425 Colorado Blvd Suite B-205 Santa Monica, CA 90404 (310) 828-6767 THE DYATLOV PASS INCIDENT 1 EXT. URAL MOUNTAINS - DYATLOV PASS - DAY 1 Helicopter footage of a dozen RESCUE WORKERS searching a snowy pass. An exceptionally tall, desolate MOUNTAIN towers over them to one side, a handful of trees litter the landscape to the other. NEWS ANCHOR (V.O.) This footage emerged from the Ural Mountains of Russia three days ago, where the search is still underway for five missing American students. 2 INT. NEWSROOM - DAY 2 A perfectly coiffed male NEWS ANCHOR speaks to the camera as the footage continues to play in a small window. NEWS ANCHOR Among the missing is the son of real estate magnate John Patrick Halvorsen, who organized and is funding the search. The rescue workers have had no luck locating the Oregon University students - who were making a documentary • recreating another ill-fated trip to the area - although they have uncovered footage from two cameras and a cell phone which they believe were with them. That footage was carefully reviewed by authorities, who decided against releasing it to the public. But today, a group of hackers calling themselves FreedomLeaks gained access to it and posted the footage on their site. The hope was that the tapes might provide an answer to the mysteries surrounding what's known as Dyatlov's Pass.