The Philosophical Brothel Author(S): Leo Steinberg Source: October, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Modernist Iconography of Sleep. Leo Steinberg, Picasso and the Representation of States of Consciousness

60 (1/2021), pp. 53–73 The Polish Journal DOI: 10.19205/60.21.3 of Aesthetics Marcello Sessa* The Modernist Iconography of Sleep. Leo Steinberg, Picasso and The Representation of States of Consciousness Abstract In the present study, I will consider Leo Steinberg’s interpretation of Picasso’s work in its theoretical framework, and I will focus on a particular topic: Steinberg’s account of “Picas- so’s Sleepwatchers.” I will suggest that the Steinbergian argument on Picasso’s depictorial modalities of sleep and the state of being awake advances the hypothesis of a new way of representing affectivity in images, by subsuming emotions into a “peinture conceptuelle.” This operation corresponds to a shift from modernism to further characterizing the post- modernist image as a “flatbed picture plane.” For such a passage, I will also provide an overall view of Cubism’s main phenomenological lectures. Keywords Leo Steinberg, Pablo Picasso, Cubism, Phenomenology, Modernism 1. Leo Steinberg and Picasso: The Iconography of Sleep The American art historian and critic Leo Steinberg devoted relevant stages of his career to the interpretation of Picasso’s work. Steinberg wrote several Picassian essays, that appear not so much as disjecta membra but as an ac- tual corpus. In the present study, I will consider them in their theoretical framework, and I will focus on a particular topic: Steinberg’s account of “Pi- casso’s Sleepwatchers” (Steinberg 2007a). I will suggest that the Steinber- gian argument on Picasso’s depictorial modalities of sleep and the -

Leonide Massine: Choreographic Genius with A

LEONIDE MASSINE: CHOREOGRAPHIC GENIUS WITH A COLLABORATIVE SPIRIT A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN'S UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF DANCE COLLEGE OF HEALTH, PHYSICAL EDUCATION AND RECREATION BY ©LISA ANN FUSILLO, D.R.B.S., B.S., M.A. DENTON, TEXAS Ml~.Y 1982 f • " /, . 'f "\ . .;) ;·._, .._.. •. ..._l./' lEXAS WUIVIAI'l' S UNIVERSITY LIBRAR't dedicated to the memories of L.M. and M.H.F. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express her appreciation to the members of her committee for their guidance and assistance: Dr. Aileene Lockhart, Chairman; Dr. Rosann Cox, Mrs. Adrienne Fisk, Dr. Jane Matt and Mrs. Lanelle Stevenson. Many thanks to the following people for their moral support, valuable help, and patience during this project: Lorna Bruya, Jill Chown, Mary Otis Clark, Leslie Getz, Sandy Hobbs, R. M., Judy Nall, Deb Ritchey, Ann Shea, R. F. s., and Kathy Treadway; also Dr. Warren Casey, Lynda Davis, Mr. H. Lejins, my family and the two o'clock ballet class at T.C.U. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION • • • . iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . iv LIST OF TABLES • . viii LIST OF FIGURES . ix LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . X Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 Purpose • • • • • • • . • • • • 5 Problem • • . • • • • • . • • • 5 Rationale for the Study • • • . • . • • • • 5 Limitations of the Study • • . • • • • • 8 Definition.of Terms • . • • . • . • • 8 General Dance Vocabulary • • . • • . • • 8 Choreographic Terms • • • • . 10 Procedures. • • • . • • • • • • • • . 11 Sources of Data • . • • • • • . • . 12 Related Literature • . • • • . • • . 14 General Social and Dance History • . • . 14 Literature Concerning Massine .• • . • • • 18 Literature Concerning Decorative Artists for Massine Ballets • • • . • • • • • . 21 Literature Concerning Musicians/Composers for Massine Ballets • • • . -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

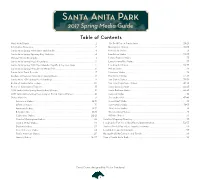

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

André Derain's

ANDRÉ DERAIN’S ‘TREES BY A LAKE: LE PARC DE CARRIÈRES-SAINT-DENIS THE COURTAULD COLLECTIONS: CONSERVATION AND ART HISTORICAL ANALYSIS WORKS FROM THE COURTAULD GALLERY PROJECT By Cleo Nisse and Francesca WhitluM-Cooper CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 ‘TREES BY A LAKE’: FORMAL AND TECHNICAL ANALYSIS 4 WHAT LIES BENEATH: A PAINTING BELOW ‘TREES BY A LAKE’ 7 TEXTURE, SCULPTURE AND DERAIN’S COLLECTION 10 ROGER FRY, LONDON AND THE COURTAULD GALLERY 14 CONCLUDING REMARKS: THE FUTURE OF ‘TREES BY A LAKE’ 17 IMAGES 19 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY 32 2 INTRODUCTION Although The Courtauld Institute of Art is renowned for both its art historical and conservation departments, these two strands of its academic activity are not always particularly integrated. Indeed, the layout of the Institute within Somerset House speaks volumes about this distinction: housed in separate wings, on either side of William Chambers’ arched entrance vestibule, the departments seem to typify the all-too-common separation between art historical and technical inquiry. In January 2012, a collaboration between The Courtauld Gallery and The Courtauld Institute of Art sought to bridge this divide. Bringing together a PhD art history student and a postgraduate in the conservation of easel paintings, it sought both to encourage collaboration between the Institute’s two halves and to shed light on one of its paintings: André Derain’s Trees by a Lake: Le Parc de Carrières-Saint-Denis. Dark in appearance and difficult to read, the painting had previously been subject to little technical or art historical analysis. Dating from 1909, it falls between the two most studied periods of Derain’s career, namely his early Fauvist period (ca. -

Motivation of the Sign 261 Discussion 287

Picasso and Braque A SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZED BY William Rubin \ MODERATED BY Kirk Varnedoe PROCEEDINGS EDITED BY Lynn Zelevansky THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK Contents Richard E. Oldenburg Foreword 7 William Rubin and Preface and Acknowledgments 9 Lynn Zelevansky Theodore Reff The Reaction Against Fauvism: The Case of Braque 17 Discussion 44 David Cottington Cubism, Aestheticism, Modernism 58 Discussion 73 Edward F. Fry Convergence of Traditions: The Cubism of Picasso and Braque 92 Discussion i07 Christine Poggi Braque’s Early Papiers Colles: The Certainties o/Faux Bois 129 Discussion 150 Yve-Alain Bois The Semiology of Cubism 169 Discussion 209 Mark Roskill Braque’s Papiers Colles and the Feminine Side to Cubism 222 Discussion 240 Rosalind Krauss The Motivation of the Sign 261 Discussion 287 Pierre Daix Appe ndix 1 306 The Chronology of Proto-Cubism: New Data on the Opening of the Picasso/Braque Dialogue Pepe Karmel Appe ndix 2 322 Notes on the Dating of Works Participants in the Symposium 351 The Motivation of the Sign ROSALIND RRAUSS Perhaps we should start at the center of the argument, with a reading of a papier colle by Picasso. This object, from the group dated late November-December 1912, comes from that phase of Picasso’s exploration in which the collage vocabulary has been reduced to a minimalist austerity. For in this run Picasso restricts his palette of pasted mate rial almost exclusively to newsprint. Indeed, in the papier colle in question, Violin (fig. 1), two newsprint fragments, one of them bearing h dispatch from the Balkans datelined TCHATALDJA, are imported into the graphic atmosphere of charcoal and drawing paper as the sole elements added to its surface. -

138904 09 Juvenilefilliesturf.Pdf

breeders’ cup JUVENILE FILLIES TURF BREEDERs’ Cup JUVENILE FILLIES TURF (GR. I) 6th Running Santa Anita Park $1,000,000 Guaranteed FOR FILLIES, TWO-YEARS-OLD ONE MILE ON THE TURF Weight, 122 lbs. Guaranteed $1 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Friday, November 1, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Al Thakhira (GB) Sheikh Joaan Bin Hamad Al Thani Marco Botti B.f.2 Dubawi (IRE) - Dahama (GB) by Green Desert - Bred in Great Britain by Qatar Bloodstock Ltd Chriselliam (IRE) Willie Carson, Miss E. Asprey & Christopher Wright Charles Hills B.f.2 Iffraaj (GB) - Danielli (IRE) by Danehill - Bred in Ireland by Ballylinch Stud Clenor (IRE) Great Friends Stable, Robert Cseplo & Steven Keh Doug O'Neill B.f.2 Oratorio (IRE) - Chantarella (IRE) by Royal Academy - Bred in Ireland by Mrs Lucy Stack Colonel Joan Kathy Harty & Mark DeDomenico, LLC Eoin G. -

January 2002 CAA News

s CUNY's Graduate Center. From 1969 to gela's Last Paintings (Oxford University CONFERENCE 1971, he was a CAA Board member, and Press, 1975); Borromini's Sari Carlo aIle was appo:inted Benjamin Frankl~ Quattro Fontane: A Study in Multiple Form SESSION Professor of the History of Art at the and Architectural Symbolism (Garland, University of Pennsylvania in Philadel 1977); The Sexuality of Christ in Renais HONORS phia in 1975. He retired in 1991, after sance Art and in Modern Oblivion (Univer teaching a semester as the Meyer sity of Chicago Press, 1983; the second Schapiro Chair at Columbia University :in edition:in 1996 was revised and doubled LEO New York. :in size by a "Retrospect" that responds to Steinberg has published and lectured critics); Ei1counters with Rauschenberg STEINBERG widely on Renaissance, Baroque, and (University of Chicago Press, 1999); and, most recently, Leonardo's Incessant Last he CAA Distinguished Scholar's Supper (Zone, 2001). Other writings Session was inaugurated in 2001 include studies of Filippo Lippi, T to engage senior scholars in the Mantegna, Michelangelo, Pontormo, Annual Conference and celebrate their Guercino, Rembrandt, Steen, VeHtzquez, contributions to art history. But its aim is and Picasso. Nonprofit Organization greater: At a time of great methodologi In addition to a prolific writing u.s. Postage cal shifts in the field, this session will career, Steinberg'S academic life has also foster dialogue within and among the been a full one. In 1982, he delivered the Paid different generations of art historians. s A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts at NewYork,N.Y. -

The Painted Word a Bantam Book / Published by Arrangement with Farrar, Straus & Giroux

This edition contains the complete text of the original hardcover edition. NOT ONE WORD HAS BEEN OMITTED. The Painted Word A Bantam Book / published by arrangement with Farrar, Straus & Giroux PUBLISHING HISTORY Farrar, Straus & Giroux hardcover edition published in June 1975 Published entirely by Harper’s Magazine in April 1975 Excerpts appeared in the Washington Star News in June 1975 The Painted Word and in the Booh Digest in September 1975 Bantam mass market edition / June 1976 Bantam trade paperback edition / October 1999 All rights reserved. Copyright © 1975 by Tom Wolfe. Cover design copyright © 1999 by Belina Huey and Susan Mitchell. Book design by Glen Edelstein. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-8978. No part o f this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information address: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 19 Union Square West, New York, New York 10003. ISBN 0-553-38065-6 Published simultaneously in the United States and Canada Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, a division of Random House, Inc. Its trademark, consisting of the words “Bantam Books” and the portrayal of a rooster, is Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada. Bantam Books, New York, New York. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BVG 10 9 I The Painted Word PEOPLE DON’T READ THE MORNING NEWSPAPER, MAR- shall McLuhan once said, they slip into it like a warm bath. -

Stein Portraits

74,'^ The Museum of Modern Art NO. 133 (D) U West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modemart PORTRAITS OF THE STEIN FAMILY The following portraits of the Steins are included in the show FOUR AMERICANS IN PARIS: THE COLLECTIONS OF GERTRUDE STEIN AND HER FAMILY. Christian Berard. "Gertrude Stein," 1928. Ink on paper (13% x 10%"). Eugene Berman. "Portrait of Alice B. Toklas," ca. I95O. India ink on paper (22 x 17"). Jo Davidson. "Gertrude Stein," ca. I923. Bronze (7 ^/k" high). "Jo Davidson too sculptured Gertrude Stein at this time. There, all was peaceful, Jo was witty and amusing and he pleased Gertrude Stein." —Gertrude Stein, Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas Jacques Lipchitz. "Gertrude Stein," I920. Bronze (I3 3/8"). "He had just finished a bust of Jean Cocteau and he wanted to do her. She never minds posing, she likes the calm of it and although she does not like sculpture and told Lipchitz so, she began to pose. I remember it was a very hot spring and Lipchitz*s studio was appallingly hot and they spent hours there. "Lipchitz is an excellent gossip and Gertrude Stein adores the beginning and middle and end of a story and Lipchitz was able to supply several missing parts of several stories. "And then they talked about art and Gertrude Stein rather liked her portrait and they were very good friends and the sittings were over." --Gertrude Stein, Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas Louis Marcoussis. "Gertrude Stein," ca. I953. Engraving (ik x 11"). Henri Matisse. -

Vente De Yearlings Mardi 19 Août Deauville

WOOTTON BASSETT 2014 2008 (IFFRAAJ ET BALLADONIA PAR PRIMO DOMINIE) GAGNANT DE GROUPE 1 ET INVAINCU À 2 ANS MEILLEUR 2 ANS FRANÇAIS DE SA GÉNÉRATION Vente de Yearlings Mardi 19 août Deauville Vente de Yearlings Vente Après la réussite aux ventes de ses premiers foals en 2013, ne manquez pas ses premiers yearlings en 2014, POUR PRÉPARER LES COURSES DE 2 ANS EN 2015 ! www.haras-etreham.fr La passion de l’élevage NICOLAS DE CHAMBURE : 06 24 27 06 42 FRANCK CHAMPION : 06 07 23 36 46 370 La Motteraye Consignment 370 Roberto Bob Back Toter Back BIG BAD BOB Marju (FR) Fantasy Girl N. Persian Fantasy Nureyev Peintre Célèbre M.b. 18/02/2013 RAFINE Peinture Bleue 2005 (GB) La Belga Roy 1998 La Baraca Qualifié F.E.E. - Breeders' Cup - Owners' Premiums in France BIG BAD BOB (2000), 8 vict., Furstenberg-Rennen (Gr.3), Prix Ridgway (L.), Autumn St.(L.), 2e Dee St.(Gr.3). Haras en 2006. Père de BERG BAHN, Brownstown St.Gr.3, BIBLE BELT, Dance Design S.Gr.3, BRENDAN BRACKAN, Solonaway St.Gr.3, BIBLE BLACK, Star Appeal St.L., BOB LE BEAU, Martin Molony St.L.,BACKBENCH BLUES, Moment of Weakness, Blaze Brightly, Banksters Bonus, 1re mère RAFINE, 7 places à 2 et 3 ans, 2e Prix du Château de Blandy-les-Tours à Fontainebleau, 4e Prix de Mogador à Longchamp. Mère de : N., (f.2012, Big Bad Bob). N., (voir ci-dessus), son troisième produit. 2e mère LA BELGA (ARG), 3 vict., GP Eliseo Ramirez (Gr.1), GP Saturnino J Unzue (Gr.1), de Potrancas (Gr.1), Carrera de las Estrellas 2yo Fillies (Gr.1), Clasico Carlos P Rodriguez (Gr.2), Sibila (Gr.2), 3e Clasico Eudoro J Balsa (Gr.3). -

The Flatbed Picture Plane

Excerpt from Other Criteria: The Flatbed Picture Plane LEO STEINBERG (1920-) I borrow the term from the flatbed printing press—‘a horizontal bed on which a horizontal printing surface rests’ (Webster). And I propose to use the word to describe the characteristic picture plane of the 1960s—a pictorial surface whose angulation with respect to the human posture is the precondition of its changed content. It was suggested earlier that the Old Masters had three ways of conceiving the picture plane. But one axiom was shared by all three interpretations, and it remained operative in the succeeding centuries, even through Cubism and Abstract Expressionism: the conception of the picture as representing a world, some sort of worldspace which reads on the picture plane in correspondence with the erect human posture. The top of the picture corresponds to where we hold our heads aloft; while its lower edge gravitates to where we place our feet. Even in Picasso’s Cubist collages, where the Renaissance worldspace concept almost breaks down, there is still a harking back to implied acts of vision, to something that was once actually seen. A picture that harks back to the natural world evokes sense data which are experienced in the normal erect posture. Therefore the Renaissance picture plane affirms verticality as its essential condition. And the concept of the picture plane as an upright surface survives the most drastic changes of style. Pictures by Rothko, Still, Newman, de Kooning, and Kline are still addressed to us head to foot—as are those of Matisse and Miró. They are revelations to which we relate visually as from the top of a columnar body; and this applies no less to Pollock’s drip paintings and the poured and Unfurls of Morris Louis.