Serbian Chant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTES. JOURNAL of MUSICOLOGY Vol

“GEORGE ENESCU” NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ARTS IAŞI FACULTY OF PERFORMANCE, COMPOSITION AND MUSIC THEORY STUDIES RESEARCH CENTER “THE SCIENCE OF MUSIC” DOCTORAL SCHOOL – MUSIC FIELD ARTES. JOURNAL OF MUSICOLOGY vol. 23-24 ARTES 2021 RESEARCH CENTER “THE SCIENCE OF MUSIC” ARTES. JOURNAL OF MUSICOLOGY Editor-in-chief – Prof. PhD Laura Vasiliu, “George Enescu” National University of Arts, Iași, Romania Senior editor – Prof. PhD Liliana Gherman, “George Enescu” National University of Arts, Iași, Romania SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Prof. PhD Gheorghe Duțică, “George Enescu” National University of Arts, Iași, Romania Prof. PhD Maria Alexandru, “Aristotle” University of Thessaloniki, Greece Prof. PhD Valentina Sandu-Dediu, National University of Music Bucharest, Romania Prof. PhD Pavel Pușcaș, “Gheorghe Dima” National Music Academy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Prof. PhD Mirjana Veselinović-Hofman, University of Arts in Belgrade, Serbia Prof. PhD Victoria Melnic, Academy of Music, Theatre and Fine Arts, Chișinău, Republic of Moldova Prof. PhD Violeta Dinescu, “Carl von Ossietzky” Universität Oldenburg, Germany Prof. PhD Nikos Maliaras, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece Lect. PhD Emmanouil Giannopoulos, “Aristotle” University of Thessaloniki, Greece EDITORS Assoc. Prof. PhD Irina Zamfira Dănilă, “George Enescu” National University of Arts, Iași, Romania Assoc. Prof. PhD Diana-Beatrice Andron, “George Enescu” National University of Arts, Iași, Romania Lect. PhD Rosina Caterina Filimon, “George Enescu” National University of Arts, Iași, Romania Assoc. Prof. PhD Gabriela Vlahopol, “George Enescu” National University of Arts, Iași, Romania Assist. Prof. PhD Mihaela-Georgiana Balan, “George Enescu” National University of Arts, Iași, Romania ISSN 2344-3871 ISSN-L 2344-3871 Translators: PhD Emanuel Vasiliu Assist. Prof. Maria Cristina Misievici DTP Ing. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures by Sean Delaine Griffin 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle by Sean Delaine Griffin Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Gail Lenhoff, Chair The monastic chroniclers of medieval Rus’ lived in a liturgical world. Morning, evening and night they prayed the “divine services” of the Byzantine Church, and this study is the first to examine how these rituals shaped the way they wrote and compiled the Povest’ vremennykh let (Primary Chronicle, ca. 12th century), the earliest surviving East Slavic historical record. My principal argument is that several foundational accounts of East Slavic history—including the tales of the baptism of Princess Ol’ga and her burial, Prince Vladimir’s conversion, the mass baptism of Rus’, and the martyrdom of Princes Boris and Gleb—have their source in the feasts of the liturgical year. The liturgy of the Eastern Church proclaimed a distinctively Byzantine myth of Christian origins: a sacred narrative about the conversion of the Roman Empire, the glorification of the emperor Constantine and empress Helen, and the victory of Christianity over paganism. In the decades following the conversion of Rus’, the chroniclers in Kiev learned these narratives from the church services and patterned their own tales of Christianization after them. The ii result was a myth of Christian origins for Rus’—a myth promulgated even today by the Russian Orthodox Church—that reproduced the myth of Christian origins for the Eastern Roman Empire articulated in the Byzantine rite. -

November 1: Registration and Welcome Reception at the Hilton Hotel Boston Downtown Financial District

November 1: Registration and Welcome Reception at the Hilton Hotel Boston Downtown Financial District November 2 - 4: Panels, Registration and Book Exhibits will take place at Hellenic College Holy Cross campus November 2 - 3: Coaches to Hellenic College Holy Cross campus depart each morning at 8:00 a.m. from the Hilton Downtown Financial District only. Coaches for the return trip to the Hilton Downtown Financial District will depart in front of the Archbishop Iakovos Library Building after the end of the receptions. On Saturday, coaches to take participants to the Cathedral Center will depart at 1:00 p.m., also from the Archbishop Iakovos Library Building. November 2 - 4: A small exhibition of Greek, Roman and Byzantine objects from the Archbishop Iakovos Collection, curated by the Very Reverend Dr. Joachim (John) Cotsonis and Dr. Maria Kouroumali, will be on display in the Archbishop Iakovos Museum, Third Floor, Archbishop Iakovos Library Building. Opening hours of exhibition: 10:00 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. (Fri - Sat.); 10:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m. (Sun) Thursday, November 1, 2012 Hilton Hotel Boston Downtown Financial District 5:00 p.m. - 8.00 p.m. Registration Hilton Lobby 6:30 p.m. - 7:30 p.m. The Mary Jaharis Center for Byzantine Art and Culture Informal Welcome Reception Kellogg Ballroom 8:00 - 10:00 p.m. BSANA Governing Board Meeting William Fly Room Friday, November 2, 2012 Hellenic College Holy Cross campus Continental Breakfast: 8:00 a.m. - 9.00 a.m. Maliotis Cultural Center Lobby Registration and Book Exhibits (all day) Maliotis Cultural Center Upper Wing 9:00 a.m. -

OCTOECHOS – DAY of the WEEK Tone 1 – 1St Canon – Ode 3

OCTOECHOS – DAY OF THE WEEK Tone 1 – 1st Canon – Ode 3 – Hymn to the Theotokos You conceived God in your womb through the Holy Spirit, and yet remained unconsumed, O Virgin. The bush unconsumed by the fire clearly foretold you to the lawgiver Moses for you received the Fire that cannot be endured. Monday – Vespers / Tuesday - Matins: Aposticha – Tone 1 O VIRGIN, WORTHY OF ALL PRAISE: MOSES, WITH PROPHETIC EYES, BEHELD THE MYSTERY THAT WAS TO TAKE PLACE IN YOU, AS HE SAW THE BUSH THAT BURNED, YET WAS NOT CONSUMED; FOR, THE FIRE OF DIVINITY DID NOT CONSUME YOUR WOMB, O PURE ONE. THEREFORE, WE PRAY TO YOU AS THE MOTHER OF GOD, // TO ASK PEACE, AND GREAT MERCY FOR THE WORLD. Tone 2 – Saturday Vespers & Friday Vespers (repeated) – Dogmaticon Dogmatic THE SHADOW OF THE LAW PASSED WHEN GRACE CAME. AS THE BUSH BURNED, YET WAS NOT CONSUMED, SO THE VIRGIN GAVE BIRTH, YET REMAINED A VIRGIN. THE RIGHTEOUS SUN HAS RISEN INSTEAD OF A PILLAR OF FLAME.// INSTEAD OF MOSES, CHRIST, THE SALVATION OF OUR SOULS. Tone 3 – Wed Matins – 2nd Aposticha ON THE MOUNTAIN IN THE FORM OF A CROSS, MOSES STRETCHED OUT HIS HANDS TO THE HEIGHTS AND DEFEATED AMALEK. BUT WHEN YOU SPREAD OUT YOUR PALMS ON THE PRECIOUS CROSS, O SAVIOUR, YOU TOOK ME IN YOUR EMBRACE, SAVING ME FROM ENSLAVEMENT TO THE FOE. YOU GAVE ME THE SIGN OF LIFE, TO FLEE FROM THE BOW OF MY ENEMIES. THEREFORE, O WORD, // I BOW DOWN IN WORSHIP TO YOUR PRECIOUS CROSS. Tone 4 – Irmos of the First Canon – for the Resurrection (Sat Night/Sun Morn) ODE ONE: FIRST CANON IRMOS: IN ANCIENT TIMES ISRAEL WALKED DRY-SHOD ACROSS THE RED SEA, AND MOSES, LIFTING HIS HAND IN THE FORM OF THE CROSS, PUT THE POWER OF AMALEK TO FLIGHT IN THE DESERT. -

THO 3347 (H 2015) – Glossary of Terms

THO 3347 (H 2015) – Glossary of Terms Akathist Literally, “not standing.” A hymn dedicated to our Lord, the Theotokos, a saint, or a holy event. Aposticha The stichera sung with psalm verses at the end of Vespers and Matins. These differ from the stichera at Psalm 140 (Vespers) and at the Praise Psalms (Matins), which are sung with fixed psalms, in that the psalm verses used (pripivs) vary with the day or feast, and do not end the singing of the whole psalm. See also stichery na stichovnych. Archieratikon Тhе book containing texts and rubrics for the solemn Hierarchical (a.k.a. Pontifical) Divine Liturgy. The Archieratikon also contains the sacrament of Ноlу Orders and special blessings and consecrations. Canon A system of nine odes (the Second Ode is sung only during Great Lent) sung at Matins after Psalm 50 and before the Praises. Each ode is connected traditionally with a scriptural canticle (see below for the nine scriptural canticles) and consists of an Irmos, a variable number of troparia and, on feasts, a katavasia. After the Third Ode a sidalen is usually sung, and after the Sixth Ode a kontakion and ikos, and after the Ninth Ode, the Svitelen is sung. The Canon has its own system of eight tones. Domatikon A theotokion sung after “Now…” (or “Glory… Now…”) at the end of Psalms 140, 141, 129, and 116 at Vespers on Friday and Saturday evenings, and on the eve of a Polyeleos saint or saints with a vigil in the same tone as the last sticheron of the saint (at “Glory…”). -

Russian Orthodoxy and Women's Spirituality In

RUSSIAN ORTHODOXY AND WOMEN’S SPIRITUALITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA* Christine D. Worobec On 8 November 1885, the feast day of Archangel Michael, the Abbess Taisiia had a mystical experience in the midst of a church service dedicated to the tonsuring of sisters at Leushino. The women’s religious community of Leushino had recently been ele vated to the status of a monastery.1 Conducting an all-women’s choir on that special day, the abbess became exhilarated by the beautiful refrain of the Cherubikon hymn, “Let us lay aside all earthly cares,” and envisioned Christ surrounded by angels above the iconostasis. She later wrote, “Something was happening, but what it was I am unable to tell, although I saw and heard every thing. It was not something of this world. From the beginning of the vision, I seemed to fall into ecstatic rapture Tears were stream ing down my face. I realized that everyone was looking at me in astonishment, and even fear....”2 Five years later, a newspaper columnistwitnessedasceneinachurch in the Smolensk village of Egor'-Bunakovo in which a woman began to scream in the midst of the singing of the Cherubikon. He described “a horrible in *This book chapter is dedicated to the memory of Brenda Meehan, who pioneered the study of Russian Orthodox women religious in the modern period. 1 The Russian language does not have a separate word such as “convent” or nunnery” to distinguish women’s from men’s monastic institutions. 2 Abbess Thaisia, 194; quoted in Meehan, Holy Women o f Russia, 126. Tapestry of Russian Christianity: Studies in History and Culture. -

TYPIKON (Arranged by Rev

TYPIKON (Arranged by Rev. Taras Chaparin) March 2016 Sunday, March 26 4th Sunday of Great Lent Commemoration of Saint John of the Ladder (Climacus). Synaxis of the Holy Archangel Gabriel. Tone 4. Matins Gospel I. Liturgy of St. Basil the Great. Bright vestments. Resurrection Tropar (Tone 4); Tropar of the Annunciation; Tropar of St. John (4th Sunday); Glory/Now: Kondak of the Annunciation; Prokimen, Alleluia Verses of Resurrection (Tone 4) and of the Annunciation. Irmos, “In You, O Full of Grace…” Communion Hymn of Resurrection and of the Annunciation. Scripture readings for the 4th Sunday of Lent: Epistle: Hebrew §314 [6:13-20]. Gospel: Mark §40 [9:17-31]. In the evening: Lenten Vespers. Monday, March 27 Our Holy Mother Matrona of Thessalonica. Tuesday, March 28 Our Venerable Father Hilarion the New; the Holy Stephen, the Wonderworker (464). Wednesday, March 29 Our Venerable Father Mark, Bishop of Arethusa; the Deacon Cyril and Others Martyred during the Reign of Julian the Apostate (360-63). Dark vestments. Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. Scripture readings for the 5th Wednesday of Lent: Genesis 17:1-9; Proverbs 15:20-16:9. Thursday, March 30 Our Venerable Father John Climacus, Author of The Ladder of Divine Ascent (c. 649). Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete. Friday, March 31 Our Venerable Father Hypatius, Bishop of Gangra (312-37). Dark vestments. Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. Scripture readings for the 5th Friday of Lent: Genesis 22:1-18; Proverbs 17:17-18:5. April 2016 Saturday, April 1 5th Saturday of Lent – Saturday of the Akathist Hymn Our Venerable Mother Mary of Egypt (527-65). -

Program Booklet

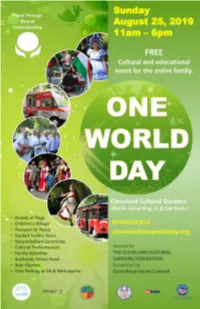

The Irish Garden Club Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians Murphy Irish Arts Association Proud Sponsors of the Irish Cultural Garden Celebrate One World Day 2019 Italian Cultural Garden CUYAHOGA COMMUNITY COLLEGE (TRI-C®) SALUTES CLEVELAND CULTURAL GARDENS FEDERATION’S ONE WORLD DAY 2019 PEACE THROUGH MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING THANK YOU for 74 years celebrating Cleveland’s history and ethnic diversity The Italian Cultural Garden was dedicated in 1930 “as tri-c.edu a symbol of Italian culture to American democracy.” 216-987-6000 Love of Beauty is Taste - The Creation of Beauty is Art 19-0830 216-916-7780 • 990 East Blvd. Cleveland, OH 44108 The Ukrainian Cultural Garden with the support of Cleveland Selfreliance Federal Credit Union celebrates 28 years of Ukrainian independence and One World Day 2019 CZECH CULTURAL GARDEN 880 East Blvd. - south of St. Clair The Czech Garden is now sponsored by The Garden features many statues including composers Dvorak and Smetana, bishop and Sokol Greater educator Komensky – known as the “father of Cleveland modern education”, and statue of T.G. Masaryk founder and first president of Czechoslovakia. The More information at statues were made by Frank Jirouch, a Cleveland czechculturalgarden born sculptor of Czech descent. Many thanks to the Victor Ptak family for financial support! .webs.com DANK—Cleveland & The German Garden Cultural Foundation of Cleveland Welcome all of the One World Day visitors to the German Garden of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens The German American National congress, also known as DANK (Deutsch Amerikan- ischer National Kongress), is the largest organization of Americans of Germanic descent. -

"Lord, I Have Cried ...", 6 Stichera: 3 for the Apostle, in Tone IV: Spec

THE 1st DAY OF THE MONTH OF OCTOBER COMMEMORATION OF THE HOLY APOSTLE ANANIAS OF THE SEVENTY COMMEMORATION OF OUR VENERABLE FATHER ROMANUS THE MELODIST AT VESPERS On "Lord, I have cried ...", 6 stichera: 3 for the apostle, in Tone IV: Spec. Mel.: "Called from on high ...": When, at the behest of the Most High, Saul was blinded * and held fast in darkness, * he came unto thee, * begging divine cleansing, * O thou who hadst received divine illumination; * then, as a wise hierarch, O most blessed one, * thou didst make him a son by adoption through baptism, * and he later adopted the whole world. * Wherefore, we bless thee with him * as an apostle of Christ, * O divinely wise Ananias: * Pray ye, that we be saved! Having all-gloriously learned things divine, * thundering forth, O blessed one, * thou didst rouse those sleeping in the graves of vanity, * who cast off mortality; * and thou didst sound the clarion * of the saving Word of God, * Who dwelt among mortals * and hath transformed those held fast in Hades, * whom thou hast made precious vessels * of Jesus the Master * and Savior of our souls, * Who hath slain death. As a bearer of light, * as preacher of God, * as a divinely chosen witness * to the sufferings of Christ * and a fellow heir and partaker * of the glory which is to come, * in that thou art with the Master, * ever delighting in the effulgence which floweth forth * from the never-waning Light, * O divinely eloquent Ananias, * by thy supplications deliver from dark misfortunes * those who now celebrate thy splendid feast. -

At the Margins of the Habsburg Civilizing Mission 25

i CEU Press Studies in the History of Medicine Volume XIII Series Editor:5 Marius Turda Published in the series: Svetla Baloutzova Demography and Nation Social Legislation and Population Policy in Bulgaria, 1918–1944 C Christian Promitzer · Sevasti Trubeta · Marius Turda, eds. Health, Hygiene and Eugenics in Southeastern Europe to 1945 C Francesco Cassata Building the New Man Eugenics, Racial Science and Genetics in Twentieth-Century Italy C Rachel E. Boaz In Search of “Aryan Blood” Serology in Interwar and National Socialist Germany C Richard Cleminson Catholicism, Race and Empire Eugenics in Portugal, 1900–1950 C Maria Zarimis Darwin’s Footprint Cultural Perspectives on Evolution in Greece (1880–1930s) C Tudor Georgescu The Eugenic Fortress The Transylvanian Saxon Experiment in Interwar Romania C Katherina Gardikas Landscapes of Disease Malaria in Modern Greece C Heike Karge · Friederike Kind-Kovács · Sara Bernasconi From the Midwife’s Bag to the Patient’s File Public Health in Eastern Europe C Gregory Sullivan Regenerating Japan Organicism, Modernism and National Destiny in Oka Asajirō’s Evolution and Human Life C Constantin Bărbulescu Physicians, Peasants, and Modern Medicine Imagining Rurality in Romania, 1860–1910 C Vassiliki Theodorou · Despina Karakatsani Strengthening Young Bodies, Building the Nation A Social History of Child Health and Welfare in Greece (1890–1940) C Making Muslim Women European Voluntary Associations, Gender and Islam in Post-Ottoman Bosnia and Yugoslavia (1878–1941) Fabio Giomi Central European University Press Budapest—New York iii © 2021 Fabio Giomi Published in 2021 by Central European University Press Nádor utca 9, H-1051 Budapest, Hungary Tel: +36-1-327-3138 or 327-3000 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ceupress.com An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched (KU). -

3 Cappella Romana Presents VENICE in the EAST: Renaissance Crete

Cappella Romana presents VENICE IN THE EAST: Renaissance Crete & Cyprus Wednesday, 8 May 2019, 7:30 p.m. Touhill Performing Arts Center, University of Missouri, Saint Louis Friday, 10 May 2019 at 7:30 p.m. Alexander Lingas Christ Church Cathedral, Vancouver, British Columbia Founder & Music Director Presented by Early Music Vancouver Saturday, 11 May 2019 at 8:00 p.m. St. Ignatius Parish, San Francisco Spyridon Antonopoulos John Michael Boyer Kristen Buhler PROGRAM Aaron Cain Photini Downie Robinson PART I David Krueger Emily Lau From the Byzantine and Venetian Commemorations of the Paschal Triduum Kerry McCarthy The Crucifixion and Deposition Mark Powell Catherine van der Salm Venite et ploremus Johannes de Quadris David Stutz soloists: Aaron Cain, Mark Powell Liber sacerdotalis (1523) of Alberto Castellani Popule meus Liber sacerdotalis soloist: Kerry McCarthy Sticherón for the Holy Passion: Ἤδη βάπτεται (“Already the pen”) 2-voice setting (melos and “ison”) Manuel Gazēs the Lampadarios (15th c.) soloists: Spyridon Antonopoulos, MS Duke, K. W. Clark 45 John Michael Boyer Traditional Melody of the Sticherarion Mode Plagal 4 Cum autem venissent ad locum de Quadris Liber sacerdotalis soloists: Aaron Cain, Mark Powell O dulcissime de Quadris Liber sacerdotalis soloists: Photini Downie Robinson, Kerry McCarthy Verses of Lamentation for the Holy Passion “Corrected by” Angelos Gregoriou MS Duke 45, Mode Plagal 2 Sepulto Domino de Quadris Liber sacerdotalis The Resurrection Attollite portas (“Lift up your gates”) Liber sacerdotalis celebrant: Mark Powell Ἄρατε πύλας (“Lift up your gates”) Anon. Cypriot (late 15th c.?), MS Sinai Gr. 1313 Attollite portas … Quem queritis … Liber sacerdotalis Χριστὸς ἀνέστη (“Christ has risen”) Cretan Melody as transcribed by Ioannis Plousiadenós (ca. -

A Byzantine Christmas

VOCAL ENSEMBLE 26th Annual Season October 2017 Tchaikovsky: All-Night Vigil October 2017 CR Presents: The Byrd Ensemble November 2017 Arctic Light II: Northern Exposure December 2017 A Byzantine Christmas January 2018 The 12 Days of Christmas in the East February 2018 Machaut Mass with Marcel Pérès March 2018 CR Presents: The Tudor Choir March 2018 Ivan Moody: The Akáthistos Hymn April 2018 Venice in the East A Byzantine Christmas: Sun of Justice 1 What a city! Here are just some of the classical music performances you can find around Portland, coming up soon! JAN 11 | 12 FEB 10 | 11 A FAMILY AFFAIR SOLO: LUKÁŠ VONDRÁCˇEK, pianist Spotlight on cellist Marilyn de Oliveira Chopin, Smetana, Brahms, Scriabin, Liszt with special family guests! PORTLANDPIANO.ORG | 503-228-1388 THIRDANGLE.ORG | 503-331-0301 FEB 16 | 17 | 18 JAN 13 | 14 IL FAVORITO SOLO: SUNWOOK KIM, pianist Violinist Ricardo Minasi directs a We Love Our Volunteers! Bach, Beethoven, Schumann, Schubert program of Italy’s finest composers. n tns to our lol volunteers o serve s users ste re o oe ersonnel osts PORTLANDPIANO.ORG | 503-228-1388 PBO.ORG | 503-222-6000 or our usns or n ottee eers n oe ssstnts Weter ou re ne to JAN 15 | 16 FEB 21 us or ou ve een nvolve sne te ennn tn ou or our otent n nness TAKÁCS QUARTET MIRÓ QUARTET WITH JEFFREY KAHANE “The consummate artistry of the Takács is Co-presented by Chamber Music Northwest ou re vlue rt o te O l n e re rteul simply breathtaking” The Guardian and Portland’5 Centers for the Arts FOCM.ORG | 503-224-9842 CMNW.ORG | 503-294-6400 JAN 26-29 FEB 21 WINTER FESTIVAL: CONCERTOS MOZART WITH MONICA Celebrating Mozart’s 262nd birthday, Baroque Mozart and Michael Haydn string quartets DEC 20 concertos, and modern concertos performed by Monica Huggett and other PDX VIVALDI’S MAGNIFICAT AND GLORIA CMNW.ORG | 503-294-6400 favorites.