St. Kilda East - HO6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Port Phillip Flag Protocol

PORT PHILLIP CITY COUNCIL FLAG PROTOCOL The Australian national flag, will be flown at mast head from the highest flagpole on every day of the year from the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls in accordance with the Flag Act 1953, with the following exceptions subject to the advice of the Chief Executive Officer: UNITED NATIONS DAY The United Nations flag will be flown all day on United Nations Day (24 October) at mast head from the highest flagpole at the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls. As part of an agreement made by the Australian Government as a member of the United Nations, the United Nations flag is to be flown in the position of honour all day on United Nations Day, displacing the Australian National flag for that day. SORRY DAY The Australian Aboriginal flag will be flown at mast head from the highest flagpole at the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls (displacing the Australian National flag) during and the week leading up to Sorry Day (26 May). NATIONAL ABORIGINAL AND ISLANDERS’ DAY OBSERVANCE COMMITTEE (NAIDOC WEEK) The Australian Aboriginal flag will be flown at mast head from the highest flagpole at the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls (displacing the Australian National flag) during and the week leading up to NAIDOC Week (first week of July). PRIDE MARCH The Rainbow Flag will be flown at mast head from the highest flagpole at the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls (displacing the Australian National flag) during and the week leading up to Pride March (January, nominated week). -

Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria: Stage One

Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria: Stage One Volume 1: Contextual Overview, Methodology, Lists & Appendices Prepared for Heritage Victoria October 2008 This report has been undertaken in accordance with the principles of the Burra Charter adopted by ICOMOS Australia This document has been completed by David Wixted, Suzanne Zahra and Simon Reeves © heritage ALLIANCE 2008 Contents 1.0 Introduction................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Context ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Project Brief .................................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Acknowledgements....................................................................................................................... 6 2.0 Contextual Overview .................................................................................................................. 7 3.0 Places of Potential State Significance .................................................................................... 35 3.1 Identification Methodology .......................................................................................................... 35 3.2 Verification of Places .................................................................................................................. 36 3.3 Application -

General Order Dated 16 May 2005 Pdf 212.13 KB

ADMINISTRATION OF ACTS General Order 2005 I, Stephen Phillip Bracks, Premier of Victoria, state that the following administrative arrangements for responsibility for the following Acts, provisions of Acts and functions will operate in place of the arrangements in operation immediately before the date of this Order: 1 General Order 2005 Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Aboriginal Lands Act 1970 Archaeological and Aboriginal Relics Preservation Act 1972 2 General Order 2005 Minister for Aged Care Health Services Act 1988 – • Sections 99, 100, 101 and 103 • Sections 11, 102, 110 and 119 in so far as they relate to supported residential services (the sections are otherwise administered by the Minister for Health) • Part 5, jointly and severally administered with the Minister for Health except for section 119 (The Act is otherwise administered by the Minister for Health) 3 General Order 2005 Minister for Agriculture Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals (Control of Use) Act 1992 Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals (Victoria) Act 1994 Agricultural Industry Development Act 1990 Biological Control Act 1986 Broiler Chicken Industry Act 1978 Conservation, Forests and Lands Act 1987 – • In so far as it relates to the exercise of powers for the purposes of the Fisheries Act 1995 (The Act is otherwise administered by the Minister for Environment and the Minister for Planning) Control of Genetically Modified Crops Act 2004 Dairy Act 2000 Domestic (Feral and Nuisance) Animals Act 1994 Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Act 1981 – • Part 4A (The -

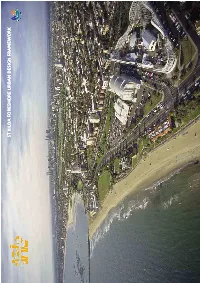

St Kilda Foreshore Urban Design Framework Acknowledgements

ST KILDA FORESHORE URBAN DESIGN FRAMEWORK ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Department of Infrastucture Pride of Place program City of Port Phillip Phillip Loone, Project Manager Joint working group—steering committee Consultants 4D Form Urbanism & Architecture David Lock Associates Integrated Urban Management Macroplan TTM Consulting Historic photographs and maps State Library of Victoria City of Port Phillip March Cover image: Oblique aerial photograph of St Kilda, 2000. Revised December CONTENTS ST KILDA FORESHORE URBAN DESIGN FRAMEWORK ................................................. 1 WHAT IS AN URBAN DESIGN FRAMEWORK? .................................................................................................................... 1 WHY AN URBAN DESIGN FRAMEWORK FOR ST KILDA FORESHORE? ...................................................................... 1 AN INTEGRATED APPROACH ................................................................................................................................................ 2 HOW TO READ THIS DOCUMENT ........................................................................................................................................ 2 THE TERMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT.............................................................................................................................. 2 PLANNING CONTEXT OF ST KILDA FORESHORE URBAN DESIGN FRAMEWORK ...... 3 POLICY CONTEXT .................................................................................................................................................................. -

City of Port Phillip Heritage Review

City of Port Phillip Heritage Review Place name: B.A.L.M. Paints Factory Citation No: Administration Building 8 (former) Other names: - Address: 2 Salmon Street, Port Heritage Precinct: None Melbourne Heritage Overlay: HO282 Category: Factory Graded as: Significant Style: Interwar Modernist Victorian Heritage Register: No Constructed: 1937 Designer: Unknown Amendment: C29, C161 Comment: Revised citation Significance What is significant? The former B.A.L.M. Paints factory administration building, to the extent of the building as constructed in 1937 at 2 Salmon Street, Port Melbourne, is significant. This is in the European Modernist manner having a plain stuccoed and brick façade with fluted Art Deco parapet treatment and projecting hood to the windows emphasising the horizontality of the composition. There is a tower towards the west end with a flag pole mounted on a tiered base in the Streamlined Moderne mode and porthole motif constituting the key stylistic elements. The brickwork between the windows is extended vertically through the cement window hood in ornamental terminations. Non-original alterations and additions to the building are not significant. How is it significant? The former B.A.L.M. Paints factory administration building at 2 Salmon Street, Port Melbourne is of local historic, architectural and aesthetic significance to the City of Port Phillip. City of Port Phillip Heritage Review Citation No: 8 Why is it significant? It is historically important (Criterion A) as evidence of the importance of the locality as part of Melbourne's inner industrial hub during the inter-war period, also recalling the presence of other paint manufacturers at Port Melbourne including Glazebrooks, also in Williamstown Road. -

City of Port Phillip Heritage Review

City of Port Phillip Heritage Review Place name: Houses Citation No: Other names: - 2409 Address: 110-118 Barkly Street & 2-6 Heritage Precinct: None Blanche Street, St Kilda Heritage Overlay: Recommended Category: Residential: Houses Graded as: Significant Style: Federation/Edwardian Victorian Heritage Register: No Constructed: 1910-1912 Designer: James Downie Amendment: C161 Comment: New citation Significance What is significant? The group of eight houses, including two pairs of semi-detached houses and one detached house at 110- 118 Barkly Street and a terrace of three houses at 2-6 Blanche Street, St Kilda, constructed from 1910 to 1912 by builder James Downie, is significant. The high timber picket fences on each property are not significant. Non-original alterations and additions to the houses and the modern timber carport at 2a Blanche Street are not significant. How is it significant? The houses 110-118 Barkly Street and 2-6 Blanche Street, St Kilda are of local historic, representative and aesthetic significance to the City of Port Phillip. Why is it significant? The group is of historical significance for their association with the residential development of St Kilda after the economic depression of the 1890s. Built between 1910 and 1912, at a time of increased population growth and economic recovery, they are representative of Edwardian-era speculative housing development on the remaining vacant sites in St Kilda. (Criterion A) They are representative examples of Federation/Edwardian housing built as an investment by a single builder using standard designs to ensure the houses could be built efficiently and economically, but with City of Port Phillip Heritage Review Citation No: 2409 variations in detailing to achieve individuality and visual interest and avoid repetition. -

General Order 22 April 2013

ADMINISTRATION OF ACTS General Order I, Denis Napthine, Premier of Victoria, state that the following administrative arrangements for responsibility for the following Acts of Parliament, provisions of Acts and functions will operate in substitution of the arrangements in operation immediately before the date of this Order: - 1 - Assistant Treasurer Accident Compensation Act 1985 – Except: • Division 1 of Part III (this Division is administered by the Attorney-General) • Division 7 of Part IV (this Division is administered by the Treasurer) Accident Compensation (Occupational Health and Safety) Act 1996 Accident Compensation (WorkCover Insurance) Act 1993 Asbestos Diseases Compensation Act 2008 Casino Control Act 1991 – • Section 128K(2) (The Act is otherwise administered by the Minister for Liquor and Gaming Regulation and the Minister for Planning) Coal Mines (Pensions) Act 1958 Crown Land (Reserves) Act 1978 – • In so far as it relates to the land shown as: o Crown Allotments 2A, 3 and 4 of Section 5, City of Melbourne, Parish of Melbourne North (Parish Plan No. 5514C) and known as the Treasury Reserve o Crown Allotments 4A and 4B on Certified Plan 111284 lodged with the Central Plan Office and to be known as the Old Treasury Building Reserve (The Act is otherwise administered by the Minister for Corrections, the Minister for Environment and Climate Change, the Minister for Health, the Minister for Major Projects, the Minister for Ports and the Minister for Sport and Recreation) Dangerous Goods Act 1985 Equipment (Public Safety) Act -

Understanding Port Melbourne: Accounting For, and Interrupting, Social Order in an Australian Suburb

Understanding Port Melbourne: Accounting for, and interrupting, social order in an Australian suburb Tracey Michelle Pahor http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8276-3751 Doctor of Philosophy February 2016 The School of Social and Political Sciences The University of Melbourne Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree Abstract Understanding may be a process rather than an end point, but any account of a place or people relies on the imposition of order. In this thesis, I use methods and concepts drawn from the work of Jacques Rancière to configure an ethnographic account of Port Melbourne, a bayside inner-suburb of Melbourne, Australia. That account, presented in three parts, demonstrates how processes through which social order is experienced, imposed and interrupted in the places people live can be studied ethnographically. In Part I, I analyse the material and social geographies described in accounts people offer of Port Melbourne, making use of the suburb’s distinctive built history to discuss what was protected in the past development and more recent planning decisions for some of Port Melbourne’s housing estates. In exploring how some people in Port Melbourne map a social geography onto the material geography, I mobilise Rancière’s conceptualisation of the imposed nature of order and argue for an understanding of this as always premised on social order. In Part II, stories and characters that I, and others, came to learn about in Port Melbourne are analysed to reveal such order to only ever be imposed, not inherent. When new arrivals, through learning the stories of Port Melbourne, enacted membership of the community of those who ‘know’ that place, they were simultaneously demonstrating the capacity to exceed the identity they had been accorded in the prevailing order. -

Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria

SURVEY OF POST-WAR BUILT HERITAGE IN VICTORIA STAGE TWO: Assessment of Community & Administrative Facilities Funeral Parlours, Kindergartens, Exhibition Building, Masonic Centre, Municipal Libraries and Council Offices prepared for HERITAGE VICTORIA 31 May 2010 P O B o x 8 0 1 9 C r o y d o n 3 1 3 6 w w w . b u i l t h e r i t a g e . c o m . a u p h o n e 9 0 1 8 9 3 1 1 group CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Background 7 1.2 Project Methodology 8 1.3 Study Team 10 1.4 Acknowledgements 10 2.0 HISTORICAL & ARCHITECTURAL CONTEXTS 2.1 Funeral Parlours 11 2.2 Kindergartens 15 2.3 Municipal Libraries 19 2.4 Council Offices 22 3.0 INDIVIDUAL CITATIONS 001 Cemetery & Burial Sites 008 Morgue/Mortuary 27 002 Community Facilities 010 Childcare Facility 35 015 Exhibition Building 55 021 Masonic Hall 59 026 Library 63 769 Hall – Club/Social 83 008 Administration 164 Council Chambers 85 APPENDIX Biographical Data on Architects & Firms 131 S U R V E Y O F P O S T - W A R B U I L T H E R I T A G E I N V I C T O R I A : S T A G E T W O 3 4 S U R V E Y O F P O S T - W A R B U I L T H E R I T A G E I N V I C T O R I A : S T A G E T W O group EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this survey was to consider 27 places previously identified in the Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria, completed by Heritage Alliance in 2008, and to undertake further research, fieldwork and assessment to establish which of these places were worthy of inclusion on the Victorian Heritage Register. -

Appendix 1 Citations for Proposed New Precinct Heritage Overlays

Southbank and Fishermans Bend Heritage Review Appendix 1 Citations for proposed new precinct heritage overlays © Biosis 2017 – Leaders in Ecology and Heritage Consulting 183 Southbank and Fishermans Bend Heritage Review A1.1 City Road industrial and warehouse precinct Place Name: City Road industrial and warehouse Heritage Overlay: HO precinct Address: City Road, Queens Bridge Street, Southbank Constructed: 1880s-1930s Heritage precinct overlay: Proposed Integrity: Good Heritage overlay(s): Proposed Condition: Good Proposed grading: Significant precinct Significance: Historic, Aesthetic, Social Thematic Victoria’s framework of historical 5.3 – Marketing and retailing, 5.2 – Developing a Context: themes manufacturing capacity City of Melbourne thematic 5.3 – Developing a large, city-based economy, 5.5 – Building a environmental history manufacturing industry History The south bank of the Yarra River developed as a shipping and commercial area from the 1840s, although only scattered buildings existed prior to the later 19th century. Queens Bridge Street (originally called Moray Street North, along with City Road, provided the main access into South and Port Melbourne from the city when the only bridges available for foot and wheel traffic were the Princes the Falls bridges. The Kearney map of 1855 shows land north of City Road (then Sandridge Road) as poorly-drained and avoided on account of its flood-prone nature. To the immediate south was Emerald Hill. The Port Melbourne railway crossed the river at The Falls and ran north of City Road. By the time of Commander Cox’s 1866 map, some industrial premises were located on the Yarra River bank and walking tracks connected them with the Sandridge Road and Emerald Hill. -

City of Port Phillip Heritage Review 10

Citation No: City of Port Phillip Heritage Review 10 Identifier Petrol filling station and Industrial premises Formerly Petrol filling station Heritage Precinct Overlay None Heritage Overlay(s) HO283 Address Cnr. Salmon St and Williamstown Rd. Category Industrial PORT MELBOURNE Constructed 1938 Designer unknown Amendment C 32 Comment Map corrected Significance The petrol filling station and industrial premises of W. Rodgerson at the NW. corner of Salmon Street and Williamstown Road were built in 1938. They are aesthetically important as a rare surviving building of their type in the Streamlined Moderne mode (Criteria B and E), being enhanced by their intact state. Primary Source Andrew Ward, City of Port Phillip Heritage Review, 1998 Other Studies Description A petrol filling station and two storeyed industrial premises at the rear in the Streamlined Moderne manner with curved canopy and centrally situated office beneath with curved and rectangular corner windows symmetrically arranged. At the rear the industrial premises are of framed construction with dark mottled brick cladding enclosing steel framed window panels at ground floor level and plain stuccoed panels above. Condition: Sound. Integrity: High. History Crown land was released for sale at Fishermen's Bend in the 1930’s. William Rodgerson purchased lot 1 of Section 67C on the north west corner of Williamstown Road and Salmon Street. It comprised one acre. In 1938, Rodgerson built a service station on the site, which twenty years later he was still operating. From the early 1960’s, Rodgerson began a business as a cartage contractor. He worked out of the same premises as W.Rodgerson Pty Ltd. -

St. Kilda Branch. St

VICTORIA REGINJE. No. DCCLXXXIV. An Act to authorize the Melbourne Tramway and Omnibus Company Limited to construct Tramway Branches in the Cities of Fitzroy Collingwood Richmond and South Melbourne and the Boroughs of St. Kilda Kew and Hawthorn and for other purposes. [3rd November 1883.] HEREAS the making of the Tra in ways hereinafter particularly Preamble, w described with their appurtenances and other works connected therewith would be of great public and local advantage: And whereas the Melbourne Tramway and Omnibus Company Limited is a Company duly incorporated under and in conformity with the provisions of " The Companies Statute 1864?7: And whereas the said Company is willing and it is expedient that it should be authorised to construct the said Tramways appurtenances and other works: Be it therefore enacted by the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty by and with the advice and consent of the Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly of Victoria in this present Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same as follows (that is to say) : — 1. This Act shall be called and may be cited as " The Melbourne short title. Tramway and Omnibus Company's Branches Act 1883." 2. Subject to the provisions of this Act the Melhourne Tramway Subject to Act and Omnibus Company Limited may construct and maintain all or any No-765- of the Tramway branches mentioned in Schedule One of this Act, and this Act shall lie read and construed for all purposes except as herein otherwise provided as part of Act DCCLXV. being " The Melhourne Tram/way and Omnibus Company's Act 1883." SCHEDULES.