Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ashton Patriotic Sublime.5.Pdf (9.823Mb)

commercial spaces like theaters, and to performances spanning the gamut from the solemn, to the joyous. This diversity encompassed celebrations outside the expected calendar of national days. Patriotic sentiment was even a key feature of events celebrating the economic and commercial expansion of the new nation. The commemorative celebration for the laying of the foundation-stone of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the “great national work which is intended and calculated to cement more strongly the union of the Eastern and the Western States,” took place on July 4, 1828.1 It beautifully illustrated the musical ties that bound different spaces together – in this case a parade route, a temporary outdoor civic space, and the permanent space of the Holliday Street Theatre. Organizers chose July Fourth for the event, wishing to signal civic pride and affective patriotism. Baltimore filled with visitors in the days before the celebration, so that on the morning of the Fourth the “immense throng of spectators…filled every window in Baltimore-street, and the pavement below….fifty thousand spectators, at least, must have been present.” The parade was massive and incorporated a great diversity of groups, including “bands of music, trades, and other bodies.” One focal point was a huge model, “completely rigged,” of a naval vessel, the “Union,” complete with uniformed sailors. Bands playing patriotic tunes were interspersed amongst the nationalist imagery on display: militia uniforms, banners emblazoned with patriotic verse, national flags, eagle figures, shields, and more. Charles Carrollton, one of the last surviving signers of the Declaration of Independence, gave the main public address at the site, accompanied by a march composed for the occasion, the “Carrollton March” (see Figure 2.4). -

Policy Making Through a Public Prism Tony Stoller Thursday 1 November

Policy making through a public prism Tony Stoller Chair, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Joseph Rowntree Housing Trust Thursday 1 November 2012 - Gresham College For a good deal of the past 40 years, I have variously observed, participated in, tried to influence, been impressed by, been appalled by, the way in which public policy has been made in the UK. Over that time, I have noted a significant shift in the relationship between the making of public policy and the way in which public discourse on policy issues is conducted. Over the next 40 minutes, I want to describe the new paradigm which has emerged to replace what we have all understood as the norm for making public policy and hearing public opinion. We no longer inhabit the age of mere „Government by spin‟. What we have now is a completely new paradigm for public policy-making, dominated and managed by what we can call the „new elite‟.1 It is a coalition of politicians, policy wonks, commentators, journalists and media owners, who both shape and comment upon policy. They are the masters now, and they jointly take part in a symbiotic dance, which the public is encouraged to believe they are part of, but from which they are in reality consciously excluded. I am going to look first this evening at the way in which that new nexus has emerged; at the consequent new policy paradigms, and the nature of the public interest within that. I will then consider a range of examples from three different sectors to illustrate how this changed way of making public policy has had its effect. -

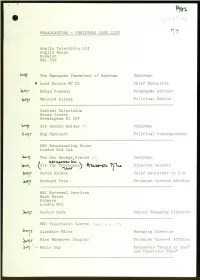

Kuoci-In Director General David Holmes� Chief Assistant to D/G

BROADCAS ING - CHRISTMAS CARD LIST Anglia Television Ltd Anglia House Norwich NR1 3JG The Marquess Townshend of Raynham Chairman * Lord Buxton MC DL Chief Executive -64-r- Brian Connell Programme Adviser Malcolm Allsop Political Editor Central Television Broad Street Birmingham Bl 2JP 1,11 Sir Gordon Hobday Chairman Reg Harcourt Political Correspondent BBC Broadcasting House London W1A IAA The Hon George Howard Chairman 10'r tanrtaVu.t (Sir Ian Trethowar) kuoci-iN Director General David Holmes Chief Assistant to D/G Bernard Tate Producer Current Affairs BBC External Services Bush House Aldwych London WC2 Austen Kark De,outy Managing Director BBC Television Contre Alasdair Milne M,,,,-nging Director ;:iss Margaret Dougla'.= Producer Current Affairs 4-1") Robin Day Presenter "World at One" aud "Question Time" • Border Television Television Centre Carlisle CA1 3NT 4.117 Professor Esmond Wright Chairman 1411 Sir John Burgess OBE TD DL JP Vice Chairman 1 James Bredin Managing Director Grampian Television Queen's Cross Aberdeen AB9 2XJ TT Cabtain lain Tennant JP Chairman Granada Television 36 Golden Square London W1R 4AH )3411 Alex Bernstein Deputy Chairman 104-41-1Sir Denis Forman OBE Chairman 14-r\1David Plowright Joint M/D 1411 Donald Harker Director of Public Affairs 1 Barrie Heads M/D Granada Intn'l HTV Wales Television Centre Cardiff CF1 9XL The Rt Hon Lord Harlech KCMG Chairman IBA 70 Brombton Road London SW3 lEY Lord Thomson of Monifieth Chalrman Sir Brian Yours,' Director General 1)7 David Glencross ITN News Ltd ITN House 48 Wells -

Britain in World Affairs: British Foreign Policy from 1945 to the Present

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Department of History HIST 292 -- Fall 2012 Britain in World Affairs: British foreign policy from 1945 to the present Prof. Klaus Larres 2 3 4 Our class meets twice a week: Tuesdays & Thursdays, 12.30-1.45pm Office hours in Room 416 Hamilton Hall: Tuesdays: 3.00-4.00pm Wednesdays: 4.00-5.00pm or by appointment Email: [email protected] (also: [email protected]) 5 BRIEF COURSE DESCRIPTION: The course provides an historical, political, and socio-economic framework for understanding British history and politics in the 20th and 21st centuries. While we will also assess important turning points in domestic British politics ― including the establishment of the welfare state, the Thatcher “revolution,” and the politics of Tony Blair’s “New Labour” ― our main focus will be on British foreign relations and the UK’s role in the world during both the Cold War and the post- Cold War years. We will also try to assess the legacy of the Blair/Browns governments and evaluate the performance of the Conservative/Lib Dem coalition government within the context of the global economic and financial crisis and the Euro crisis which have had a considerable impact on the UK. Particular attention will be paid to the following: 1. the legacies of Britain’s imperial past and the repercussions of Britain’s victory in World War II on the country’s post-1945 role in the world; 2. Britain’s economic performance and the mismatch between resources and “punching above” the country’s weight in world politics; 3.