Gert-Matthias Wegner: a Personal Encounter with India, Its Music and Its Food Though Utterly Personal, Based on My Own Experien

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swaroop Sampradaya 1 ______

The Swaroop Sampradaya 1 _______________________________________________________________________________________ The Swaroop Sampradaya Akkalkot Niwasi Shree Swami Samarth “This book attempts to showcase the life of the exalted masters of the Swaroop Sampradaya and gives a brief outlook of the tremendous humanitarian work undertaken by the followers of this sect for the spiritual and material upliftment of the common man” The Swaroop Sampradaya 2 _______________________________________________________________________________________ Copyright 2003 Shree Vitthalrao Joshi charities Trust First Edition All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or transmitted by any means - electronic or otherwise -- including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without the express permission in writing from: Shree Vitthalrao Joshi Charities Trust, C-28, 'Suyash'/ 'Parijat', 2nd Floor, Near Amar Hind Mandal, Gokhale Road (North), Dadar (West), Mumbai, Pin Code: 400 028, Maharashtra State, INDIA. Shree Vitthalrao Joshi Charities Trust The Swaroop Sampradaya 3 _______________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Swaroop-Sampradaya........................................................................................................... 5 Lord Dattatreya..................................................................................................................... 6 Shrimad Nrusimha Saraswati - Incarnation of Lord Dattareya .......................................... -

The Face of God a Most Soul Stirring Biography of a Living God

The Face of God A Most Soul Stirring Biography of a Living God Yogi Mahajan THE FACE OF GOD YOGI MAHAJAN MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED, DELHI Contents Sr.No. Particulars Page No. 1 An Ancient Prophecy Comes True 7 2 The Shalivahanas 10 3 Childhood 14 4 Freedom Struggle 17 5 Marriage 20 6 A Young Enterprise 28 7 Opening the Thousand Petalled Lotus 30 8 Sahaja Yoga 34 9 Spreading on the Wings of Love 41 10 Meeting with 'Gagangiri Maharaj' 50 11 A Born Architect 51 12 A Legal Battle 62 13 Agriculture 68 14 Divine Economist 70 15 A Great Patron of Music 74 16 "With the Sun and the Moon Under Her Feet" 78 17 75th Birthday 82 18 Shri Kalki 86 19 Appendix 89 Writer's Note "If there is a God, what does He look like?" To see the face of God is the seeker's burning desire. But God does not reveal Himself. In the annals of human record, it happened once, in the era of the Mahabharata, when Shri Krishna revealed His Divine form to Prince Arjuna on the battlefield. Moses is said to have heard the commandments of God, but he could not see His face amidst blinding light. Mohammed the Prophet also did not see the face of God, although he had Divine revelations. But God loves His children so much so, that in His compassion He manifests among human beings in their hour of need, as did Shri Rama, Shri Krishna and the son of God - Jesus Christ. -

Parliamentary Information

The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LlV NO.3 SEPTEMBER 2008 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CBS Publishers & Distributors ] ], Darya Ganj, New Delhi-2 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor P.D. T. Achary Secretary-General Lok Sabha Associate Editors N.K. Sapra Additional Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Dr. Ravinder Kumar Chadha Joint Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Assistant Editors Smt. Renu SadaIfa Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Smt. Swapna Bose Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Smt. Neelam Sethi Joint Director II Lok Sabha Secretariat o Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi EDITORIAL NOTE The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association is an association of Commonwealth parliamentarians united by the pursuit of the high ideals of parliamentary democracy. The CPA has within its fold a large number of national, state, provincial and territorial Parliaments and Legislatures. Three years from now, the Association will be completing 100 years of its fruitful existence. During its long and chequered history, the CPA has played a laudable role in upholding parliamentary democracy by enhancing knowledge and understanding of democratic governance. Through its endeavours, Parliaments and peoples of the Commonwealth from diverse backgrounds, have forged close links and mutually benefited in various areas related to governance. The CPA has also been encouraging Regional Conferences among its Branches to devote special attention to matters of regional interest. The CPA Branches of the North-East region of India have been organizing Regional Conferences every year since 1997. These Conferences have provided a forum for legislators of this Region to discuss issues of common concem and also the problems and prospects of parliamentary democracy in the region. -

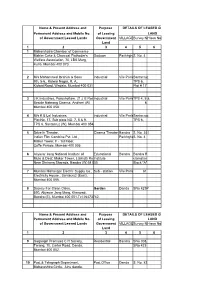

Name & Present Address and Purpose DETAILS of LEASED

INFORMATION ON LEASED GOVERNEMNT LANDS IN MUMBAI SUB DISTRICT TALUKA : ANDHERI Name & Present Address and Purpose DETAILS OF LEASED GOVERNMENT Permanent Address and Mobile No. of Leasing LAND of Government Leased Lands Government VILLAGESurvey No.Hissa No. Land 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 Maharshatra Chamber of Commerce Mahim Coke & Charcoal Flathoder's Godown ParikhgharS. No. 4 Welfare Association, 70, LBS Marg, Kurla, Mumbai 400 070. 2 M/s Mohammed Ibrahim & Sons Industrial Vile ParleSantacruz 9th, 5-6,, Kidwai Nagar, R. A., TPS 6, Kidwai Road, Wadala, Mumbai 400 031 Plot # 17 3 J K Industries, Purushottam, 21,J B RoadIndustrial Vile ParleTPS 4, 5 & Beside Nabrang Cinema, Andheri (W) 6 Mumbai 400 058. 4 M/s K B Lal Industries, Industrial Vile ParleSantacruz Plot No. 17, Sub plots NO. 7, 8 & 9. TPS 6, TPS 6, Santacruz (W), Mumbai 400 054. 5 Drive In Theatre, Cinema Theatre Bandra S. No. 341 Indian Film Combine Pvt. Ltd., ParkhgharS. No. 4 Maker Tower, F - 1st Floor, Cuffe Parade, Mumbai 400 005. 6 Aliyavar Jang National Institute of Educational Bandra Bandra Re Mute & Deaf, Maker Tower, Labhatti Road,Institute clamation Near Shrirang Sharada, Bandra (W) M 050 Block "A" 7 Mumbai Mahangar Electric Supply Co., Sub - station Vile Parle 61 Electricity House., Santacruz (East), Mumbai 400 055. 8 Society For Clean Cities, Garden Danda SNo 423P 590, Aliyavar Jang Marg, Kherwadi, Bandra (E), Mumbai 400 051.Tel 26473742. Name & Present Address and Purpose DETAILS OF LEASED GOVERNMENT Permanent Address and Mobile No. of Leasing LAND of Government Leased Lands Government VILLAGESurvey No.Hissa No. -

Chapter 2: the Guru Darshan (From the Eternal One)

Chapter 2: The Guru Darshan Searching for the Sadguru with total devotion and longing leads to success in locating Him. In this chapter, amongst other details, I will also describe the circumstances under which various devotees met Bhagavan Nityananda and realized that he was their Guru. Pitfalls in the path Once, a lady visited our home at Vajreshwari. She appeared to be very pious and her looks resembled an ascetic. She wore an ochre saree, left her hair loose and adorned her forehead with a very large vermilion tika. The ladies of my house were pleased at her impressive presence and got overwhelmed by her elaborate sermons. Her entry into our house was instantaneous and the members of the family treated her with the respect due to a visiting saint. She performed some miracles, including materializing kumkum in her palm. All the womenfolk were mesmerized by her charisma and surrendered to her demands. However, one fine morning the lady disappeared as dramatically as she had appeared, and so did some of our valuables. There was no trace of her. The family was saddened that a stranger could dupe them so easily. Within no time, our family rushed to have the darshan of Bhagavan Nityananda. Baba was staying at Vaikuntha at that time. The moment they stepped inside the hall, Baba muttered, “Bunch of fools. Trusting all and sundry! Blindly watching a magic show!” They all felt ashamed. After having a Guru of Baba’s stature, it was indeed very stupid to get carried away by someone who performed so called ‘miracles’. -

142 Tourism Resources and Sustainable

I J R S S I S, Vol. V (1), Jan 2017: 142-148 ISSN 2347 – 8268 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCHES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND INFORMATION STUDIES © VISHWASHANTI MULTIPURPOSE SOCIETY (Global Peace Multipurpose Society) R. No. MH-659/13(N) www.vmsindia.org TOURISM RESOURCES AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF TOURISM IN KOLHAPUR DISTRICT: A GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS Shubhangi S. Kale and Sambhaji D. Shinde P.D.V.P. Mahavidyalaya, Shivaji University, Tasgaon, Dist. Sangli Kolhapur Abstract Tourism is an e ver growing se rvice industry with underlying immense potential growth. It is an ancient phenomenon which has been exists in social communities since long back. Present day it has become a social and economical phenomenon. Kolhapur is one of the leading tourist district can be develop in the state of Maharashtra (India). Healthy atmosphe re of the Kolhapur district located at South Western part of Maharashtra attracts tourists from all corne rs of the country, in the present pape r an attempt has been made to classify tourist destinations in Kolhapur district, for that are assessing present status and classification of tourism. Stress is also given on untapped classification of tourism as an industry. It is obse rved that there are lots of tourist’s attractions in and around the district of Kolhapur. Similarly the district of Kolhapur is enriched with a rich biodiversity making it one of the 35 biodiversity hotspots in the world. It is observed that there are lots of tourist’s attractions in and around the district of Kolhapur. Keywords : Observations, Tourist Destinations, Physiographical Setup, Classification and Tourism Potential Growth. -

Small Industries Development Bank of India

Small Industries Development Bank of India Actual disbursement of subsidy to Units will be done by banks after fulfillment of stipulated terms & conditions Date of issue 18-07-2014 vide sanction order No. 22/CLTUC/RF-1/SIDBI/14-15 (Amount in Rs.) Sl.no Amount of NAME OF THE UNIT ADDRESS sanctioned subsidy 1 JAY POLY PET JULELAL COLONY,FULCHUR ROAD,GONDIA 174879 2 PERFECT ENTERPRISE 59, MAHADEV ESTATE-4, CTM-RAMOL ROAD, AHMEDABAD- 224000 380026 3 Standard Auto General Muzaffarnagar Road Shamli(UP)-247776 1500000 Engineering 4 Uttarakhand Packaging F-249, Prashant Vihar, Rohini, Delhi 1200000 5 POLYLUX FOAM INDUSTRIES 1, SARDAR ESTATE, NR JAY AMBEY MILL, PALDI ROAD, VISNAGAR 481950 6 JOEL STUDIO AND GOOD HOPE PLAZA, NEAR POST OFFICE, PIRAVOM 239000 MEENCHIRAPADATH IT 7 NEELKANTH PACKAGING PLOT NO: 3, SHUBHLAKSHMI ESTATE, SARKHEJ BABULAL 157500 HIGHWAY, MORIYA, TK. SANAND 8 S.G. Print -N- Pack Industries Plot No13,4th Phase, Industrial Area, Gamaharia,District-Saraikela 607000 Kharswan (Jharkhand) 9 NICHE REPROGRAPHICS Vrindavanam, Udiyankulangara, Amaravila PO 279843 10 Khyati Tin Poster Company 1320 Akhunj Gali, Raipur, Gomtipur, Ahmedabad 375000 11 GURU OFFSHORE AND MARINE PLOT NO 1-210/A,GIDC-2,DEDIYASAN,GUJARAT 1486972 ENGINEERS 12 MS HETVI FASHIONS UNIT-1019,INDRAJIT SOCIETY,MAHAVIR NAGAR,B/H-NAVRATNA 455400 CHAMBER,OPP DIAMOND MILL COMPOUND,NIKOL 13 Guru Woodern Laser Dies Plot No 11/12 Parsottram estate B/H Sardar Estate , Ajwa road 392332 14 SUDARSHAN MARMO PVT LTD NH-8,VILLAGE-MORCHANA,DIST-RAJSMAND 1325926 15 SRINISONS WIRING -

Shree Maharaj Biography Part1

A Short Biography of Shree Sadguru Digambardas Maharaj 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ A short biography of “Shree Sadguru Digambardas Maharaj” A Short Biography of Shree Sadguru Digambardas Maharaj 2 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Copyright ? 2002 Shree Vitthalrao Joshi charities Trust First Edition All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or transmitted by any means - electronic or otherwise -- including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without the express permission in writing from: Shree Vitthalrao Joshi charities Trust, C-28, 'Suyash'/ 'Parijat', 2nd Floor, Near Amar Hind Mandal, Gokhale Road (North), Dadar (West), Mumbai, Pin Code: 400 028, Maharashtra State, INDIA. Shree Vitthalrao Joshi Charities Trust A Short Biography of Shree Sadguru Digambardas Maharaj 3 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Anantakoti Brahmanda Nayaka Rajadhiraj Yogiraj Shree Sadguru Digambardas Maharaj Ki Jai A Short Biography of Shree Sadguru Digambardas Maharaj 4 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Part I Preface...........................................................................................................................6 Konkan-Land of Saints - birthplace............................................................................12 -

Synergistic Financial Networks Private Limited E

SYNERGISTIC FINANCIAL NETWORKS PRIVATE LIMITED E-WASTE RECYCLING POLICY The Information and Communication revolution has brought enormous changes in the way we organize our lives, our economies, industries and institutions. These spectacular developments in modern times have undoubtedly enhanced the quality of our lives, but at the same time, have led to manifold problems including the problem of massive amount of hazardous waste and other waste generated from electric products. Such waste poses a serious threat to human health and environment. The issue of proper management of such hazardous E-Waste is therefore critical to the protection of livelihood, health and environment. To deal with this ever-rising problem of E-Waste, the government of India, through its Ministry of Environment and forest, formulated the E-Waste (Management and Handling) Rules in 2016. SYNERGISTIC FINANCIAL NETWORKS PRIVATE LIMITED STANDS COMMITTED TO IMPLEMENT THE E-WASTE RULES. The Basel Convention defines wastes as- “Substances or objects, which are disposed of or are intended to be disposed of or are required to be disposed of by the provisions of national laws”. E waste has been defined as- “Waste electrical and electronic equipment, whole or in part or rejects from their manufacturing and repair process, which are intended to be discarded.” Whereas, Electrical and electronic equipment has been defined as "Equipment which is dependent on electrical currents or electro-magnetic fields to fully functional". Like hazardous waste, the problem of e-waste has become an immediate and long-term concern as its unregulated accumulation and recycling can lead to major environmental problems endangering human health. -

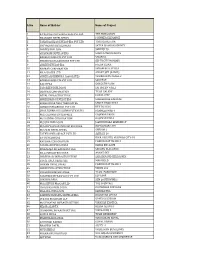

S No Name of Builder Name of Project 1 E-City Projects Constructions Pvt

S No Name of Builder Name of Project 1 E-City Projects Constructions Pvt. Ltd. THE BUNGLOWS 2 NIJANAND DEVELOPERS PUSHKER ELEGANCE 3 TAKSHASHILA DEVELOPERS PVT LTD TAKSHSHILA AIR 4 SATYAGRAH DEVELOPERS SATYA GRAH RESIDENCY 5 SHREEJI BUILCON SHREEJI 78 6 SHARNAM DEVELOPERS SHRII NAND HEIGHTS 7 BAKERI PROJECTS PVT LTD SIVANTA 8 SHRINIVAS ORGANISORS PVT LTD SUPERCITY HONOUR 9 SHREE DEVELOPERS PALAK ELINA 10 NIRMAN CORPORATION SHYAM BELLEVILLE 11 NILA SPACES LTD ANANT SKY (RANIP) 12 SHREE SADHIKRUPA ASSOCIATES VRUNDAVAN PEARL 2 13 BAKERI PROJECTS PVT LTD SARVESH 14 RAJ INFRA SANGATH PALM 15 SAI GREEN BUILDCON SAI GREEN VALLY 16 UDAYRAJ CORPORATION TULSI GALAXY 17 ROYAL INFRASTRUCTURE ROYAL CITY 18 SHREEDHAR DEVELOPERS SHREEDHAR PARIVAR 19 SHREE DHAR NEST ASSOCIATES SHREE DHAR NEST 20 SOHAM INFRABUILD PVT LTD DEV PRAYAG 21 SHAILESHBHAI KALUBHAI VEKARIYA PARMESHWAR 6 22 M/S GAJANAN ENTERPRISE GAJANAN PRIDE 23 M/S RIDDHI CORPORATION GAJANAN VILLA 24 M/S JDR INFRACON JASHU DHARA RESIDENCY 25 M/S DIVYAJIVAN INFRASTRUCTURE DIVYAJIVAN CITY 26 M/S M M DEVELOPERS SHIVAM 2 27 TATHYA INFRASPACE PVT LTD ASHRAY 10 28 B.V DEVELOPERS DIVA HEIGHTS, VISHWAS CITY-10 29 KAVISHA CORPORATION PABBLE BAY PHASE 2 30 DARSHAN DEVELOPERS MANSI ENCLAVE 31 MAHARAJA INFRASTRUCTURE SARANG ELEGANCE 32 NILA INFRASTRUCTURE ANANT SKY 33 SHREE HARI INFRASTRUCTURE SAHAJANAND HELICONYA 34 SAFAL GALA REALITIES MARIGOLD 35 SHIVAM DEVELOPERS PABBLE BAY PHASE 2 36 SHREE INFRASTRUCTURE VIVAN 101 37 TULSI INFRASTRUCTURE TULSI PARKVIEW 38 PARSHWA INFRASPACE PVT LTD RJ PRIME 39 SUN BUILDERS -

Kolhapur District Tourism Plan Kolhapur District Tourism Plan 2012

KOLHAPUR DISTRICT TOURISM PLAN KOLHAPUR DISTRICT TOURISM PLAN 2012 Total Estimated Expenditure Rs. 520 crore District Collector, Kolhapur 2 CONTENTS PART - A Introduction 1 - 4 Survey – Survey method 5 Classification of Tourist Destinations 6 - 7 Domestic and Foreign Visitors 8 Classification of Tourist Destinations as per their importance 9 Class ‘C’ Pilgrimage and religious places 10 Actual Observation Charts 11 - 21 SWOT Analysis 22 - 26 Classification – Discussion 27 – 30 Maps – As per classification 31 - 35 Brief Information of Tourist Destinations (All Talukas) 36 - 63 Intra city Tourism of kolhapur 64 - 67 Tourist Destinations in Kolhapur City 68 - 75 New Projects 76 - 87 Directions for Intra-city Tourism 88 Directions for transport/ Hotel professionals 88 Do’s and Don’t’s for historical places 89 Hunar Se Rojagar 90 - 112 Packages for Tourists 113 - 114 Funding Agencies 115 -119 ANNEXURE Bed and Breakfast Maharashtra Tourism Policy G. R. of Maharashtra Government G. R. of Maharashtra Government – Eco tourism PART - B Particulars of Development Work New Projects 3 Introduction In today’s busy, fast stressful life the need to get away from it all has become an essential part of life. As a result the number of people opting out for travelling to far away tourist destinations is on the rise. People have a varied purpose during their trips like visiting religious places, historical monuments, sightseeing on new locations, entertainment, etc. Thus tourism has become an important industry, contributing to income source for the local population and adding to the per capita income and GDP in general. There are a lot of tourist attractions in and around the district of Kolhapur. -

KONKAN DARSHAN Day 1 : Early Morning Departure from A

KONKAN DARSHAN Day 1 : Early morning departure from a convenient location or your doorstep. Stop for breakfast at Nagothane, the gateway to the Alphonso Belt. Proceed to Lord Parshuram Temple, Parashurama a Brahmin, the sixth avatar of Vishnu, belongs to the Treta yug, and is the son of Jamadagani and Renuka. Parashu means axe, hence his name literally means Rama-with-the-axe. He received an axe after undertaking a terrible penance to please Shiva, from whom he learned the methods of warfare and other skills. He fought the advancing ocean back thus saving the lands of Konkan and Malabar. The coastal area of Kerala state along with the Konkan region, i.e., coastal Maharashtra and Karnataka, is also sometimes called Parashurama Kshetra (Parashurama's country). Parashurama is said to be a "warrior Brahman", the first warrior saint. His mother is descended from the Kshatriya Suryavansham clan that ruled Ayodhya. Lunch. Check – in at Sawantwadi. (BLED) Day 2 : Have Breakfast and proceed to Amboli / Sawantwadi sightseeing . Stay at Sawantwadi. (BLED) Day 3 : Have Breakfast and proceed to Devbaug Sangam. Have Lunch and proceed for Scuba Diving & Snorkelling. Visit Jay Ganesh Temple, Situated at Malvan Jay Ganesh temple is now on a ‘must see’ list of tourists. The temple is built by Shri Jayantrao Salgaonkar, an astrologer of repute and creator of very popular almanac ‘Kalnirnay’. Situated in Medha locality of Malvan on ancestral family land of Salgaonkars, the temple has been constructed as per the holy principles of temple architecture in India. Shri Jayantrao personally supervised the construction. The presiding deity in the temple is Lord Ganesha, much revered Elephant God of Maharashtra.