The Trial of Breaker Morant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bruce Beresford's Breaker Morant Re-Viewed

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 30, núm. 1 (2020) · ISSN: 2014-668X The Boers and the Breaker: Bruce Beresford’s Breaker Morant Re-Viewed ROBERT J. CARDULLO University of Michigan Abstract This essay is a re-viewing of Breaker Morant in the contexts of New Australian Cinema, the Boer War, Australian Federation, the genre of the military courtroom drama, and the directing career of Bruce Beresford. The author argues that the film is no simple platitudinous melodrama about military injustice—as it is still widely regarded by many—but instead a sterling dramatization of one of the most controversial episodes in Australian colonial history. The author argues, further, that Breaker Morant is also a sterling instance of “telescoping,” in which the film’s action, set in the past, is intended as a comment upon the world of the present—the present in this case being that of a twentieth-century guerrilla war known as the Vietnam “conflict.” Keywords: Breaker Morant; Bruce Beresford; New Australian Cinema; Boer War; Australian Federation; military courtroom drama. Resumen Este ensayo es una revisión del film Consejo de guerra (Breaker Morant, 1980) desde perspectivas como la del Nuevo Cine Australiano, la guerra de los boers, la Federación Australiana, el género del drama en una corte marcial y la trayectoria del realizador Bruce Beresford. El autor argumenta que la película no es un simple melodrama sobre la injusticia militar, como todavía es ampliamente considerado por muchos, sino una dramatización excelente de uno de los episodios más controvertidos en la historia colonial australiana. El director afirma, además, que Breaker Morant es también una excelente instancia de "telescopio", en el que la acción de la película, ambientada en el pasado, pretende ser una referencia al mundo del presente, en este caso es el de una guerra de guerrillas del siglo XX conocida como el "conflicto" de Vietnam. -

A Study Guide by Robert Lewis

© ATOM 2014 A STUDY GUIDE BY ROBERT LEWIS http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-450-9 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au OVERVIEW In 1902 two Australian soldiers were CURRICULUM arrested for killing prisoners, held in APPLICABILITY prison, allowed access to a lawyer to but his trial and hasty execution was Breaker Morant: The Retrial prepare their defence only one day a cover up for commanding officers is a resource that be used by before the trial started, denied access who issued orders to take no prison- middle and upper secondary to a key witness during the trial, found ers which they later denied. The high students in guilty, and sentenced to death. They command was imposing a program were executed one day after they were of murder and near genocide in a History: told they had been found guilty. campaign to subjugate the local Boer - The development of population in South Africa all for the Australian national identity Could this be a fair trial? purpose of controlling the newly dis- - Federation and the Early covered goldfields. Commonwealth Should an injustice be righted even - Australia and the Boer War after more than 100 years? This was the first war to be filmed by Legal Studies: the newly invented movie camera and - Law and Justice The two soldiers who were treated this the international telegraph meant that way were Lt Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant for the first time events across the Film Studies: and Lt Peter Handcock. world could be on the front page the - Documentary Film next day. The film Breaker Morant The Retrial (Gregory Miller And Nick Bleszynski, In this film fully dramatised scenes 2013, 2 x 52 minute episodes) expos- illustrate the complex story. -

The British Concentration Camp Policy During the Anglo-Boer War

Barbaric methods in the Anglo-Boer War Using Barbaric Methods in South Africa: The British Concentration Camp Policy during the Anglo-Boer War James Robbins Jewell. The Boer War, which is frequently referred to as Britain's Vietnam or Afghanistan, was marked by gross miscalculations on the part of both British military and political leaders. In their efforts to subdue the Boers, Britain used more troops, spent more money, and buried more soldiers than anytime between the Napoleonic wars and World War I - a century during which it had been busy expanding its empire. Despite the miscalculations, lapses in judgement, and blatant stupidity demonstrated throughout the war by the British leaders, historically speaking, one policy remains far more notorious than any other. Unable to bring the war to a conclusion through traditional fighting, the British military, and in particular the two men who were in command, Frederick, Baron Roberts and Herbert, Baron Kitchener, responded to the Boer use of guerilla warfare by instituting a scorched earth combined with a concentration camp policy.! Nearly forty years later, Lord Kitchener's decision to institute a full-scale concentration camp strategy came back to haunt the British. On the eve of the Second World War, when a British ambassador to Gernlany protested Nazi camps, Herman Goering rebuffed the criticism by pulling out an encyclopedia and looking up the entry for concentration camps, which credited the British with being the first to use them in the Boer War.2 Under the scrutiny that comes with the passage of time, the concentration camp policy has rightfully been viewed as not only inhumane, but hopelessly flawed. -

RECONNAISSANCE Autumn 2021 Final

Number 45 | Autumn 2021 RECONNAISSANCE The Magazine of the Military History Society of New South Wales Inc ISSN 2208-6234 BREAKER MORANT: The Case for A Pardon Battle of Isandlwana Women’s Wartime Service Reviews: Soviet Sniper, Villers-Bretonneux, Tragedy at Evian, Atom Bomb RECONNAISSANCE | AUTUMN 2021 RECONNAISSANCE Contents ISSN 2208-6234 Number 45 | Autumn 2021 Page The Magazine of the Military History Society of NSW Incorporated President’s Message 1 Number 45 | Autumn 2021 (June 2021) Notice of Next Lecture 3 PATRON: Major General the Honourable Military History Calendar 4 Justice Paul Brereton AM RFD PRESIDENT: Robert Muscat From the Editor 6 VICE PRESIDENT: Seumas Tan COVER FEATURE Breaker Morant: The Case for a Pardon 7 TREASURER: Robert Muscat By James Unkles COUNCIL MEMBERS: Danesh Bamji, RETROSPECTIVE Frances Cairns 16 The Battle of Isandlwana PUBLIC OFFICER/EDITOR: John Muscat By Steve Hart Cover image: Breaker Morant IN FOCUS Women’s Wartime Service Part 1: Military Address: PO Box 929, Rozelle NSW 2039 26 Service By Dr JK Haken Telephone: 0419 698 783 Email: [email protected] BOOK REVIEWS Yulia Zhukova’s Girl With A Sniper Rifle, review 28 Website: militaryhistorynsw.com.au by Joe Poprzeczny Peter Edgar’s Counter Attack: Villers- 31 Blog: militaryhistorysocietynsw.blogspot.com Bretonneux, review by John Muscat Facebook: fb.me/MHSNSW Tony Matthews’ Tragedy at Evian, review by 37 David Martin Twitter: https://twitter.com/MHS_NSW Tom Lewis’ Atomic Salvation, review by Mark 38 Moore. Trove: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-532012013 © All material appearing in Reconnaissance is copyright. President’s Message Vice President, Danesh Bamji and Frances Cairns on their election as Council Members and John Dear Members, Muscat on his election as Public Officer. -

An Infantry Officer in Court – a Review of Major James Francis Thomas As Defending Officer for Lieutenants Breaker Morant, Pe

An Infantry Officer In Court – A Review of Major James Francis Thomas as Defending Officer for Lieutenants Breaker Morant, Peter Handcock and George Witton – Boer War Commander James Unkles, RANR Introduction Four men from Australia who joined the Boer war were to be connected by destiny in events that still intrigue historians to this day. Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant, Peter Handcock, George Ramsdale Witton and James Francis Thomas were to meet in circumstances that saw Morant and Handcock executed and Witton sentenced to life imprisonment following military Courts Martial in 1902. This article attempts to review the experiences of Major Thomas, a mounted infantry officer from Tenterfield who joined British Forces as a volunteer and ended up defending six officers, including Breaker Morant on charges of shooting Boer prisoners History of the Boer Wars 1880 - 1902 The Boer War commenced on 11 October 1899, and was fought in three distinct phases. During the first phase the Boers were in the ascendancy. In their initial offensive moves, 20,000 Boers swept into British Natal and encircled the strategic rail junction at Ladysmith. In the following weeks, Boer troops besieged the townships of Mafeking and Kimberley. Phase 1 reached its climax in what has become known as ‘Black Week’ – 10 to15 December 1899. In this one week, three British armies, each seeking to relieve the besieged townships, suffered massive and humiliating defeats in the battles of Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso. These defeats shook the British Empire. In response, Britain despatched two regular divisions and replaced the ill-starred General Sir Redvers Buller, with the Empire’s most eminent soldier, Field Marshall Lord Roberts VC, as its commander in South Africa. -

Useful Knowledge 35 Spring 2014

The Magazine of the Mechanics’ Institutes Of Victoria Inc. UsefulNo. Knowledge35 – Spring 2014 PO Box 1080, Windsor VIC 3181 Australia ISSN 1835-5242 Reg No. A0038156G ABN 60 337 355 989 Price: Five Dollars $5 "LEST WE FORGET" There would hardly be a Hall in Victoria or its Some of those who returned formed Soldier adjoining Reserve, or a nearby cenotaph that Settlements, or laboured at community projects, the words ‘Lest we Forget’ are not recorded. like the Great Ocean Road. The phrase is from Rudyard Kipling’s The A hundred years on this is an opportunity for Recessional penned for Queen Victoria’s your Hall, your community to… ‘remember them’. Diamond Jubilee in 1897. This Anzac Day why ‘Lest we forget – Lest we not also remember ‘the forget’ is repeated after going down of the sun’ an entreaty that we will with a lowering of the first four verses as on far off battlefields of Jesus Christ. kick on to a ‘welcome notThose forget threethe sacrifice iconic home’the flag. dance It couldto all localthen words ‘Lest we forget’ service personnel. A are often added at the conclusion of Laurence of Will Longstaff’s Menin Gate at midnight by Will Longstaff Binyon’s famousreflection painting at midnight ‘Menin For the Fallen. Photo from: Collection Database of the Australian ‘They shall not grow old, Gate at Midnight’ when War Memorial under the ID Number: ART09807 as we that are left grow those ghostly legions old/ Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn./ At the going of white crosses or any resting place, with the down of the sun and in the morning,/ We will sounding of The Reveillerise and aagain Roll Call from of district fields remember them. -

A Case Study of the Natal Witness

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF THE NATAL WITNESS by MARYLAWHON Submitted in partial fulfillment ofthe academic requirements for the degree of Master in Environment and Development in the Centre for Environment and Development, School ofApplied Environmental Sciences University ofKwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg 2004 ABSTRACT The media has had a significant impact on spreading environmental awareness internationally. The issues covered in the media can be seen as both representative of and an influence upon the heterogeneous public. This paper describes the environmental reporting in the South African provincial newspaper, the Natal Witness, and considers the results to both represent and influence South African environmental ideology. Environmental reporting In South Africa has been criticised for its focus on 'green' environmental issues. This criticism is rooted in the traditionally elite nature of both the media and environmentalists. However, both the media and environmentalists have been noted to be undergoing transformation. This research tests the veracity of assertions that environmental reporting is elitist, and has found that the assertions accurately describe reporting in the Witness. 'Green' themes are most commonly found, and sources and actors tend to be white and men. However, a broad range of discourses were noted, showing that the paper gives voice to a range of ideologies. These results hopefully will make a positive contribution to the environmental field by initiating debate, further studies, and reflection on the part of environmentalists, journalists, and academics on the relationship between the media and the South African environment. The work described in this dissertation was carried in the Centre for Environment and Development, University ofKwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, from July 2004 to December 2004, under the supervision ofProfessor Robert Fincham. -

A Teaching Guide by William Bigelo W Introduction and Summary of Lessons

Witness Apartheid: A Teaching Guide by William Bigelo w Introduction and Summary of Lessons . 3 Day One: Apartheid Simulation . ?C Day 'bo: Film-Witness to Apartheid . 7 Day Three: Role Play4 New Breed of Children" . 9 Day Four: Role Play4 New Breed of Children" (completion) . 11 Day Five: South Africa Letter Writing. 13 Reference Materials . 14 Additional Reading Suggestions for Student. Reading Suggestions for lkachers Additional Film Suggestions Student Handout #1 Privileged Minority. .......................... 15 Student Handout #2 The Bantustans . 16 Student Handout #3 Human Rights Fact Sheet. 17 Student Handout #4 Learning Was Defiance . 19 Student Handout #5 South African Student . 21 Student Handout #6 Challenging "Gutter Education". 23 a1987 Copyright by William Bigelow Published by The Southern Africa Media Center California Newsreel, 630 Natoma Street, San Francisco, CA 94103, (415) 621-6196 This "Raching Guide" made possible by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Design, typesetting, and production by Allogmph, San Francisco Film, Witness to Apartheid (classroom version): 35 minutes, 1986 Produced and directed by Sharon Sopher Co-produced by Kevin Harris Classroom version of Witness to Apartheid made possible by the Aaron Diamond Foundation. Introduction The story Witness to Apartheid tells is stark: children in South Africa - the same age as students we teach - are today being beaten, detained, even tortured. As one recent human rights report summarizes, the South African government is waging a 'kar against children.'' The images of Witness to Apartheid are not seen on the evening news: a father shares his feelings about the cold-blooded murder of his son by a South African policeman; a young woman describes the hideous torture she experienced while in police custody; a young man mumbles that he doesn't want to go on living - his beatings by security forces have left him permanently disabled. -

The Influence of the Friendly Society Movement in Victoria 1835–1920

The Influence of the Friendly Society Movement in Victoria 1835–1920 Roland S. Wettenhall Post Grad. Dip. Arts A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 24 June 2019 Faculty of Arts School of Historical and Philosophical Studies The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT Entrepreneurial individuals who migrated seeking adventure, wealth and opportunity initially stimulated friendly societies in Victoria. As seen through the development of friendly societies in Victoria, this thesis examines the migration of an English nineteenth-century culture of self-help. Friendly societies may be described as mutually operated, community-based, benefit societies that encouraged financial prudence and social conviviality within the umbrella of recognised institutions that lent social respectability to their members. The benefits initially obtained were sickness benefit payments, funeral benefits and ultimately medical benefits – all at a time when no State social security systems existed. Contemporaneously, they were social institutions wherein members attended regular meetings for social interaction and the friendship of like-minded individuals. Members were highly visible in community activities from the smallest bush community picnics to attendances at Royal visits. Membership provided a social caché and well as financial peace of mind, both important features of nineteenth-century Victorian society. This is the first scholarly work on the friendly society movement in Victoria, a significant location for the establishment of such societies in Australia. The thesis reveals for the first time that members came from all strata of occupations, from labourers to High Court Judges – a finding that challenges conventional wisdom about the class composition of friendly societies. -

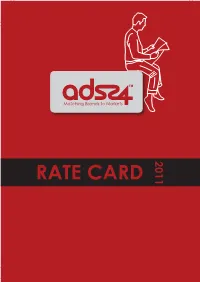

RATE CARD ROP Rates Summary (MON-FRI) 1 Jan - 31 Dec 2011

2011 RATE CARD ROP Rates Summary (MON-FRI) 1 Jan - 31 Dec 2011 Beeld (Mon, Tues) Beeld (Wed, Thurs, Fri) BEELD BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC BEELD BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Beeld Main Body R163.10 R228.60 R228.60 R228.60 Beeld Main Body R169.40 R237.40 R237.40 R237.40 Sake 24 R164.00 R192.00 R230.00 R230.00 Sake 24 R164.00 R192.00 R230.00 R230.00 Sport 24 R163.10 R228.60 R228.60 R228.60 Sport 24 R169.40 R237.40 R237.40 R237.40 BEELD BEELD SUPPLEMENTS BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC BEELD SUPPLEMENTS BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Jip R127.00 R172.50 R172.50 R172.50 Leefstyl R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 Buite Beeld R146.10 R201.60 R201.60 R201.60 Motors R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 Vrydag R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 BEELD Oos Beeld R 46.10 R 64.80 R 64.80 R 64.80 Tshwane Beeld R 86.00 R113.60 R 113.60 R113.60 Mpumalanga Beeld R 42.00 R 60.10 R 60.10 R 60.10 Noordwes Beeld R 42.00 R 60.10 R 60.10 R 60.10 Wes Beeld R 40.90 R 54.60 R 54.60 R 54.60 Huisgids R 86.00 R113.60 R 113.60 R113.60 Die Burger (Mon, Tues) Die Burger (Wed, Thurs, Fri) DIE BURGER Wes BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC DIE BURGER Wes BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Burger Wes Main Body R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Main Body R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Burger Wes Promosies R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Promosies R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Burger Wes Sake 24 R103.00 R119.00 R157.00 R157.00 Burger Wes Sake 24 R103.00 R119.00 R157.00 R157.00 Burger Wes Sport 24 R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Sport 24 R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Jip Wes R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Leefstyl -

Publications Brochure Newspapers

NEWS TRAVEL LIFESTYLE MEN SCIENCE & TECH WOMEN ENTERTAINMENTSPORT 2019 Beeld 3 Rapport 4 The Witness 5 NEWSPAPERS Sunday Sun 6 Daily Sun 7 Die Burger 8 Copyright © 2019 Media24 Volksblad 9 City Press 10 DistrictMail 11 Hermanus Times 12 Paarl Post 13 Weslander 14 Worcester Standard 15 3 Beeld is an award-winning Afrikaans newspaper that’s published six days a week in Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West. TARIFFS Newspapers Cover price Days of Region Monthly the week debit order Beeld Monday - R12.50 Gauteng R231 Monday - Friday Friday issue Beeld Monday - R12.50 Gauteng R280 Monday - Saturday Friday issue Saturday R13.50 Gauteng issue Beeld R12.50 Saturday only Gauteng R50 Saturday only Copyright © 2019 Media24 4 Rapport offers exclusive news on politics, sport and people, 16 pages with opinions, analyses and book reviews in Weekliks, lifestyle news in Beleef, business news in Sake, job opportunities in Loopbane and a newsmaker profile by Hanlie Retief. TARIFFS Newspapers Cover price Days of Region Monthly the week debit order Rapport R12.50 Sunday only National R101 Copyright © 2019 Media24 5 The Witness is a broadsheet morning newspaper that’s published Monday to Friday in KwaZulu-Natal. Weekend Witness is a tabloid which appears on Saturdays and provides a mix of news, commentary, sport, personal finance, entertainment and a popular weekly property sales supplement. TARIFFS Newspapers Cover price Days of Region Monthly the week debit order The Witness Monday - R7.70 KZN R119 Monday - Friday Friday issue The Witness Monday - R7.70 KZN R144 Monday - Saturday Friday issue Saturday R7.90 KZN issue The Witness R7.90 Saturday only KZN R25 Saturday only Copyright © 2019 Media24 6 Sunday Sun is an exciting Sunday tabloid filled with entertainment and lots of celebrity news. -

South African Crime Quarterly 57

The killing fields of KZN Local government elections, violence and democracy in 2016 Mary de Haas* [email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2016/v0n57a456 This article explores the intersections between party interests, democratic accountability and violence in KwaZulu-Natal. It begins with an overview of the legacy of violence in the province before detailing how changes in the African National Congress (ANC) since the 2007 Polokwane conference are inextricably linked to internecine violence and protest action. It focuses on the powerful eThekwini Metro region, including intra-party violence in the Glebelands hostel ward. These events provide a crucial context to the violence preceding the August 2016 local government elections. The article calls for renewed debate about how to counter the failure of local government. In KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), the province dubbed the Glebelands hostel ward. Crucially, it also the ‘killing fields’ in the early 1990s, all post- contextualises the violence that preceded the 1994 elections have been marked by intimidation August 2016 local government elections. and violence. In the past decade intra-party Political violence 1994–2015 conflict, especially over the nomination of local government ward candidates, has increased. The violence that engulfed KZN in the 1980s In 2011 the conflict within the African National and early 1990s continued for several years Congress (ANC) went beyond individual after the 1994 elections, with an estimated competition and was symptomatic of increasing