Morality and the Rule of Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hayek's the Constitution of Liberty

Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty An Account of Its Argument EUGENE F. MILLER The Institute of Economic Affairs contenTs The author 11 First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Foreword by Steven D. Ealy 12 The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Summary 17 Westminster Editorial note 22 London sw1p 3lb Author’s preface 23 in association with Profile Books Ltd The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve public 1 Hayek’s Introduction 29 understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society, by analysing Civilisation 31 and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Political philosophy 32 Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2010 The ideal 34 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a PART I: THE VALUE OF FREEDOM 37 retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. 2 Individual freedom, coercion and progress A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. (Chapters 1–5 and 9) 39 isbn 978 0 255 36637 3 Individual freedom and responsibility 39 The individual and society 42 Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or to reprint should be sought from the Limiting state coercion 44 Director General at the address above. -

Catholics, Slaveholders, and the Dilemma of American Evangelicalism, 1835–1860 / W

Catholics, Slaveholders, and the Dilemma of American Evangelicalism, 1835 –1860 W. J ASON WALLACE University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana © 2010 University of Notre Dame Press Copyright © 2010 by University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 www.undpress.nd.edu All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wallace, William Jason. Catholics, slaveholders, and the dilemma of American evangelicalism, 1835–1860 / W. Jason Wallace. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-268-04421-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-268-04421-X (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. United States—Church history—19th century. 2. Evangelicalism— United States—History—19th century. 3. Catholic Church— United States—History—19th century. 4. Slavery—United States— History—19th century. 5. Christianity and politics—United States— History—19th century. I. Title. BR525.W34 2010 282'.7509034—dc22 2010024340 ∞ The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. © 2010 University of Notre Dame Press Introduction Between 1835 and 1860, evangelical pulpits and religious journals in the North aggressively attacked slaveholders and Catholics as threats to American values. Criticisms of these two groups could often be found in the same northern evangelical journal, if not on the same page. Words such as “despotism” and “tyranny” described both the theological condi- tion of the Catholic Church and the political condition of the South. Slavery and Catholicism were labeled incompatible with republican insti- tutions and bereft of the virtues necessary to sustain a democratic people. -

Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (In a Constitutional Democracy)

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) Imer Flores Georgetown Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-161 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1115 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2156455 Imer Flores, Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy), in LAW, LIBERTY, AND THE RULE OF LAW 77-101 (Imer B. Flores & Kenneth E. Himma eds., Springer Netherlands 2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Chapter6 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) lmer B. Flores Tse-Kung asked, saying "Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one's life?" K'ung1u-tzu said: "Is not reciprocity (i.e. 'shu') such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not ckJ to others." Confucius (2002, XV, 23, 225-226). 6.1 Introduction Taking the "rule of law" seriously implies readdressing and reassessing the claims that relate it to law and liberty, in general, and to a constitutional democracy, in particular. My argument is five-fold and has an addendum which intends to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western civilizations, -

United Nations Convention Documents in Light of Feminist Theory

Michigan Journal of Gender & Law Volume 8 Issue 1 2001 United Nations Convention Documents in Light of Feminist Theory R. Christopher Preston Brigham Young University Ronald Z. Ahrens Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjgl Part of the International Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation R. C. Preston & Ronald Z. Ahrens, United Nations Convention Documents in Light of Feminist Theory, 8 MICH. J. GENDER & L. 1 (2001). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjgl/vol8/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Gender & Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION DOCUMENTS IN LIGHT OF FEMINIST THEORY P, Christopher Preston* RenaldZ . hrens-* INTRODUCTION • 2 I. PROMINENT FEMINIST THEORIES AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL LAW • 7 A Liberal/EqualityFeminism 7 B. CulturalFeminism . 8 C. DominanceFeminism • 9 1. Reproductive Capacity • 11 2. Violence . 12 3. Traditional Male Domination of Society • 12 II. WOMEN'S RIGHTS IN INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTS • 13 A. United Nations Charter • 14 B. UniversalDeclaration of Human Rights • 15 C. The Two InternationalCovenants • 15 1. International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights • 16 2. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights • 16 D. Convention on the Elimination ofAll Forms of DiscriminationAgainst Women • 17 E. The NairobiForward Looking Strategies • 18 F. -

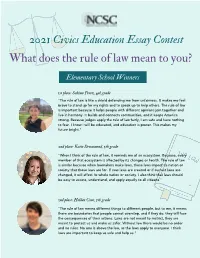

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Rule-Of-Law.Pdf

RULE OF LAW Analyze how landmark Supreme Court decisions maintain the rule of law and protect minorities. About These Resources Rule of law overview Opening questions Discussion questions Case Summaries Express Unpopular Views: Snyder v. Phelps (military funeral protests) Johnson v. Texas (flag burning) Participate in the Judicial Process: Batson v. Kentucky (race and jury selection) J.E.B. v. Alabama (gender and jury selection) Exercise Religious Practices: Church of the Lukumi-Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah (controversial religious practices) Wisconsin v. Yoder (compulsory education law and exercise of religion) Access to Education: Plyer v. Doe (immigrant children) Brown v. Board of Education (separate is not equal) Cooper v. Aaron (implementing desegregation) How to Use These Resources In Advance 1. Teachers/lawyers and students read the case summaries and questions. 2. Participants prepare presentations of the facts and summaries for selected cases in the classroom or courtroom. Examples of presentation methods include lectures, oral arguments, or debates. In the Classroom or Courtroom Teachers/lawyers, and/or judges facilitate the following activities: 1. Presentation: rule of law overview 2. Interactive warm-up: opening discussion 3. Teams of students present: case summaries and discussion questions 4. Wrap-up: questions for understanding Program Times: 50-minute class period; 90-minute courtroom program. Timing depends on the number of cases selected. Presentations maybe made by any combination of teachers, lawyers, and/or students and student teams, followed by the discussion questions included in the wrap-up. Preparation Times: Teachers/Lawyers/Judges: 30 minutes reading Students: 60-90 minutes reading and preparing presentations, depending on the number of cases and the method of presentation selected. -

Birth & Reconstruction of Equality in the United States Nascimento E

BIRTH & RECONSTRUCTION OF EQUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES NASCIMENTO E RECONSTRUÇÃO DA IGUALDADE NOS ESTADOS UNIDOS Alexander Tsesis Loyola University School of Law (Chicago, IL, USA) Recebimento: 13 jan. 2020 Aceitação: 26 jan. 2020 Como citar este artigo / How to cite this article (informe a data atual de acesso / inform the current date of access): TSESIS, Alexander. Birth & reconstruction of equality in the United States. Revista da Faculdade de Direito UFPR, Curitiba, PR, Brasil, v. 64, n. 3, p. 75-106 set./dez. 2019. ISSN 2236-7284. Disponível em: <https://revistas.ufpr.br/direito/article/view/72128>. Acesso em: 11 mar. 2020. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/rfdufpr.v64i3.72128. ABSTRACT The United States was born of a normative and political aspiration asserted in its declaration of independence. The document did not simply contain a list of reasons for ending colonialization, but established equality as key ideal which remained imbedded in the nation’s ethos and is central for the U.S. representative democracy. Despite the normative statements of human rights, the status of the United States was deeply tainted because the framers of the Constitution retained protections for the institution of slavery. But many other legal and cultural anomalies also existed from the inception of nationhood, including the subjugation of women and the retention of propertied privileges as qualifications for voting and obtaining political offices. Amendments that were made to the Constitution after the Civil War (1861-1865) significantly advanced the rule of law but simultaneously required greater sincerity in abiding to the founding testament. Reconstruction in the United States was achieved through amendment of the original Constitution rather than the enactment of a new document. -

Equal Right of Men and Women to the Enjoyment of the Rights Set Forth in the Covenant

CCPR General Comment No. 18: Non-discrimination Adopted at the Thirty-seventh Session of the Human Rights Committee, on 10 November 1989 1. Non-discrimination, together with equality before the law and equal protection of the law without any discrimination, constitute a basic and general principle relating to the protection of human rights. Thus, article 2, paragraph 1, of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights obligates each State party to respect and ensure to all persons within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction the rights recognized in the Covenant without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Article 26 not only entitles all persons to equality before the law as well as equal protection of the law but also prohibits any discrimination under the law and guarantees to all persons equal and effective protection against discrimination on any ground such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. 2. Indeed, the principle of non-discrimination is so basic that article 3 obligates each State party to ensure the equal right of men and women to the enjoyment of the rights set forth in the Covenant. While article 4, paragraph 1, allows States parties to take measures derogating from certain obligations under the Covenant in time of public emergency, the same article requires, inter alia, that those measures should not involve discrimination solely on the ground of race, colour, sex, language, religion or social origin. -

Rule of Law Freedom Prosperity

George Mason University SCHOOL of LAW The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywick 02-20 LAW AND ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id= The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywicki* After decades of neglect, interest in the nature and consequences of the rule of law has revived in recent years. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered renewed interest in the nature of the rule of law in the Anglo-American tradition. Meanwhile, economists have increasingly come to realize the importance of political and legal institutions, especially the presence of the rule of law, in providing the foundation of freedom and prosperity in developing countries. The emerging economies of Eastern Europe and the developing world in Latin America and Africa have thus sought guidance on how to grow the rule of law in these parts of the world that traditionally have lacked its blessings. This essay summarizes the philosophical and historical foundations of the rule of law, why Bush v. Gore can be understood as a validation of the rule of law, and explores the consequences of the presence or absence of the rule of law in developing countries. I. INTRODUCTION After decades of neglect, the rule of law is much on the minds of legal scholars today. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered a renewed interest in the Anglo-American tradition of the rule of law.1 In the emerging democratic capitalist countries of Eastern Europe, societies have struggled to rediscover the rule of law after decades of Communist tyranny.2 In the developing countries of Latin America, the publication of Hernando de Soto’s brilliant book The Mystery of Capital3 has initiated a fervor of scholarly and political interest in the importance and the challenge of nurturing the rule of law. -

A Theory of Equality Before the Law∗

A Theory of Equality Before the Law Daron Acemoglu Alexander Wolitzky MIT MIT September 11, 2020 Abstract We propose a simple model of the emergence of equality before the law. A society can support effort (“cooperation”, “pro-social behavior”) using the carrot of future cooperation or the stick of coercive punish- ment. Community enforcement relies only on the carrot and involves low coercion, low inequality, and low effort. A society in which elites control the means of violence supplements the carrot with the stick, and involves high coercion, high inequality, and high effort. In this regime, elites are privileged by both laws and norms: because they are not subject to the same punishments as non-elites, norms are also more favorable for them. Nevertheless, it may be optimal– even from the elites’perspective– to establish equality before the law, where all agents are subject to the same coercive punishments and norms are more equal. The key mechanism is that equality before the law increases elites’effort, which improves the carrot of future cooperation and thus encourages even higher effort from non-elites. Equality before the law combines high coercion and low inequality. Factors that make equality before the law more likely to emerge include limits on the extent of coercion, greater marginal returns to effort, increases in the size of the elite group, greater political power for non-elites, and under some additional conditions, lower economic inequality. Keywords: rule of law, social norms, repeated games, community enforcement, coercion, inequality. JEL Classification: D70, P16, P51, K10, C73. We thank Bob Gibbons, Gillian Hadfield, Rachel Kranton, Suresh Naidu, Jean Tirole, John Wallis, the anonymous referees, and seminar participants at Georgetown, MIT, Northwestern, the 2018 NBER Organizational Economics meetings, and the 2019 CIFAR Institutions, Organizations, and Growth meetings for useful discussions and comments. -

Roberto Unger, the Catholic Bishops and Distributive Justice Gerard F

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 2 Article 13 Issue 1 Symposium on the Economy February 2014 Critical Legal Bishops: Roberto Unger, the Catholic Bishops and Distributive Justice Gerard F. Powers Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Gerard F. Powers, Critical Legal Bishops: Roberto Unger, the Catholic Bishops and Distributive Justice, 2 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 201 (1987). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol2/iss1/13 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT COMMENTS CRITICAL LEGAL BISHOPS: ROBERTO UNGER, THE CATHOLIC BISHOPS AND DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE GERARD F. POWERS* The second draft of the bishops' pastoral letter on the economy calls for a new "experiment in securing economic rights."' The bishops assert that "economic rights should be granted a status in the cultural and legal traditions of this na- tion analogous to that held by the civil and political rights to freedom of religion, speech, and assembly." 2 This assertion of the importance of economic rights provides substance to the normative demands of a "preferential option for the poor." s While it has descriptive and hortatory meaning,4 as a principle of distributive justice,5 the option for the poor gives * A.B. 1980, Princeton University; J.D., M.A. -

Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law John A

Washington University Jurisprudence Review Volume 9 | Issue 1 2016 Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law John A. Bruegger Follow this and additional works at: http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Theory Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation John A. Bruegger, Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law, 9 Wash. U. Jur. Rev. 081 (2016). Available at: http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Jurisprudence Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREEDOM, LEGALITY, AND THE RULE OF LAW JOHN A. BRUEGGER ABSTRACT There are numerous interactions between the rule of law and the concept of freedom. We can see this by looking at Fuller’s eight principles of legality, the positive and negative theories of liberty, coercive and empowering laws, and the formal and substantive rules of law. Adherence to the rules of formal legality promotes freedom by creating stability and predictability in the law, on which the people can then rely to plan their behaviors around the law—this is freedom under the law. Coercive laws can actually promote negative liberty by pulling people out of a Hobbesian state of nature, and then thereafter can be seen to decrease negative liberty by restricting the behaviors that a person can perform without receiving a sanction. Empowering laws promote negative freedom by creating new legal abilities, which the people can perform.