Expansion Report 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moor Park, Blackpool

Moor Park, Blackpool SuDS used Swales Basins Benefits Control of runoff to greenfield runoff rate. Wetland features manage runoff to ensure clean water enters the natural drainage system. Significantly lower cost of installation over a conventional piped or underground drainage. Massive biodiversity potential. Engagement with school staff and students. Anticipated involvement of local people and potentially Moor Park Friends Group. 1. Location Junction of Bispham Road and Bristol Avenue, north of Blackpool town centre, Lancashire, next to the former TVR car factory. 2. Description The Moor Park development is a large healthcare building, incorporating leisure and library uses as well as new play areas and a multi-use games area. It is set in the north-west corner of an existing park, Moor Park, in the residential neighbourhood of Bispham. The building is served by a large (200 space) car parking area. It lies at roughly 10m AOD and is broadly flat, falling to the south. The development site is around 3.4ha, including the surrounding earthworks and ‘soft’ play areas. Surface water drainage is to a combined sewer running underneath the site (pre-existing drainage). Soils are mixed, but incorporate a high proportion of sands. 1 Case study www.susdrain.org Figure 1 Moor Park masterplan (David Singleton) 2 Case study www.susdrain.org Figure 2 Building layout (David Singleton) 3 Case study www.susdrain.org 3. Main SuDS used From the very early stages of the project, the proposed location of such a large development in a designated green space demanded a high level of sensitivity and a landscape led approach. -

Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool and Lancashire Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (Local Strategy)

Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool and Lancashire Appendix 5(c) Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (Local Strategy) For more information about the Lancashire and Blackpool Flood Risk Management Strategy please contact:- Flood Risk Management Teams Lancashire County Council Cuerden Offices Highways Department Cuerden Way Preston PR5 6BS Blackpool Council Bickerstaffe Hose Blackpool FY1 1AD [email protected] Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool and Lancashire Appendix 5(c) Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (Local Strategy) CONTENTS Executive Summary to be completed at the end Introduction Flood and Water Management Act Objectives & Measures Past & Future A Joint Local Strategy Other Sources of Flooding Our Vision for Local Flood Risk Management 1. Theme One - Roles and Responsibilities for Managing Flood Risk 2. Theme Two – Understanding Risk – Local Flood Risk within Lancashire 3. Theme Three – Sustainable Flood Risk Management Spatial Planning and Sustainable Drainage 4. Theme Four – Communication and Involvement 5. Theme Five – Funding 6. Theme 6 – Achieving a Nation of Climate Champions Summary Moving Forward – Implementing and Reviewing our Strategy Appendix 1 Glossary Business Plan Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool and Lancashire Appendix 5(c) Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (Local Strategy) Lancashire Strategic Partnership Exec Summary to be completed and signed by Members of all 3 authorities Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool and Lancashire Appendix 5(c) Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (Local Strategy) Figure 1 - Typical Flooding from local sources By courtesy of Cumbria County Council Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool and Lancashire Appendix 5(c) Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (Local Strategy) Introduction Flood & Water Management Act The Flood and Water Management Act 2010 (FWMA) has put many of the recommendations made by the Pitt Review into legislation and as a result County Councils and Unitary Authorities have been designated as Lead Local Flood Authorities (LLFAs). -

Name of Deceased

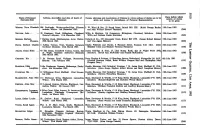

Name of Deceased Names, addresses and descriptions of Persons to whom notices of claims arc to be given Date before which Address, description and date of death of Deceased notices of claims (Surname first) and names, in parentheses, of Personal Representatives to be given BINDER, Walter George Oakleigh, Cryers Hill, Hughenden, near High Lloyds Bank Limited, Executor and Trustee Department, P.O. Box 116, 165 The 6th May 1969 Wycombe, Bucks, Timber Merchant (Retired). 7th Parade, Watford, Kent's (Ref. BD BW/76591/5), or Reynolds, Parry-Jones & (654) February 1969. Crawford, 10 Easton Street, High Wycombe, Bucks, Solicitors. (Lloyds Bank Limited, Florence Alice Binder, Walter Edward Binder and Alan George Binder.) READ, Thomas Alfred ... 25 Angerstein Road, North End, Portsmouth, Hants, Goodman and Kent, 21 Hampshire Terrace, Portsmouth, Solicitors. (Peter Goodman 6th May 1969 Lieutenant Commander, Royal Navy, Retired. 27th and Stanley Styles.) (655) g November 1968. DYHOUSE, George Mark 23 Harold Road, Southsea, Portsmouth, Hants, Goodman and Kent, 21 Hampshire Terrace, Portsmouth, .Solicitors. (Sheila Robertson 6th May 1969 £ Coppersmith, H.M. Dockyard, Retired. 19th Dec- and Frederick Arthur Bellman.) (656) g ember 1968. STEPHENSON, Dora Braeburn House, Moor Lane, Eastfield, Scarborough, Midland Bank Executor and Trustee Company 'Limited, United House, P.O. Box 7, 8th May 1969 i Yorkshire, Spinster. 25th January 1969. Piccadilly, York, YO1 1XL. (657) Q LAKING, Frank 2 Brumby Grove Cottages, Scotter Road, Scunthorpe, William Bains, 205-207 High Street, Scunthorpe, Lines, Solicitors. (Elsie Maud 7th May 1969 Lines, Builder. 15th April 1968. Laking.) (658) 8 BENNETT, Alice Jane ... 140 High Street, Wootton Bassett, Swindom, Wilt- H. -

BOAR's HEAD V. PORTSMOUTH

OFFICIAL PROGRAMME FOR FIRST FOOTBALL EVENING NEWS] f RESULTS see the special KEY-CODE in the EVENING Specie/ NEWS on sale here, and link it with the SCOREBOARD before you leave the ground KEY-CODE the end of the game. MOTF The teams selected by The l^i w I t Evening News onnot'be Che Vol. XXI—No. 36 SATURDAY, MARCH 6th, 1954 Price 3d. SERVICE uname or in the same order as those chosen for the half-time scores in she Club programme wmm V HALF-TIME SCORES v. PORTSMOUTH Matches for Saturday, March 6th, 1954 First name opposite the letter represents the home team. W signifies match CLUB NOTES abandoned. Key for to-day's matches is as follows: — Making their second visit to The WATCH PETER HARRIS. Half Valley within six weeks are Ports Throughout the years, Portsmouth Half CLUBS CLUBS Time Time mouth, who, readers will recall, de have only once been defeated at The feated Charlton here during extra Valley in League or Cup, and a time in the third round replay of BOLTON WANDERERS . WEST BROMWICH A... player who always seems to do well the F.A. Cup on January 14. In the against Charlton is Peter Harris, SUNDERLAND SHEFFIELD UNITED .. next round, Portsmouth had three the brilliant Pompey outside-right. BURNLEY FULHAM games with Scunthorpe before they Peter hag been in great form of late, B ARSENAL L BLACKBURN ROVERS. earned a fifth round ticket, and and was selected for the England then, after drawing at Bolton, they "B" team against Scotland at Sun LIVERPOOL LEEDS UNITED lost 2—1 to the Wanderers at Fratton derland on Wednesday, but unfor HUDDERSFIELD TOWN . -

Dwfitness Club & Smyths Toys Unit

DW FITNESS CLUB & SMYTHS TOYS UNIT VICARAGE LANE, BLACKPOOL, LANCASHIRE, FY4 4NB SECURE, LONG LET LEISURE AND RETAIL WAREHOUSE INVESTMENT WITH FIXED UPLIFTS DW FITNESS CLUB & SMYTHS TOYS UNIT VICARAGE LANE, BLACKPOOL, LANCASHIRE, FY4 4NB SECURE, LONG LET LEISURE AND RETAIL WAREHOUSE INVESTMENT WITH FIXED UPLIFTS INVESTMENT CONSIDERATIONS ■ City Fringe Gym Investment and Retail Warehouse ■ Total area of 54,857 sqft (5,096.2 sq m) ■ Site area of 4.3 acres (1.74 hectares) Investment situated on the busy Vicarage Lane ■ Fully let to the strong covenants of Dave Whelan ■ The vendor is seeking offers in excess of£4,750,000 within close proximity to Blackpool city centre Sports Limited and Smyths Toys UK Limited (Four Million Seven Hundred and Fifty Thousand ■ The town has an extensive catchment population ■ Attractive average weighted unexpired lease term Pounds) subject to contract and exclusive of VAT. and benefits fromexcellent accessibility with the of 14.4 years (12.8 years to break) Based on this level of pricing, the net initial yield A583 & A5230 linking Blackpool to the M55 and reflects 7.5%, assuming standard purchasers costs. ■ A584 coast road, which connects the city to the Producing a total rent of £377,257 pa, equating affluent Lytham St. Anne’s. to a low passing rent of £6.88 psf YIELD PROFILE ■ Freehold April 2021 8.57% April 2026 9.87% ■ Benefits from on-site car parking for approximately 200 cars. *based on forecast RPI at 2.5% Pen rose Av e D A O R E E R T Y R R E H DW FITNESS CLUB & SMYTHS TOYS UNIT VICARAGE LANE, BLACKPOOL, -

With Vivian Beiswenger © 2014 Cunard Lines

SNOWBIRDS - SKIP THE WINTER 2015 or 2016 Full or Partial World Cruises on the Three Queens EUROPE & BLACKPOOL 2015 Up to 121 days. January-April 2015 or 2016 include: ® QUEEN MARY 2 Transatlantic Crossings to/from 13-day Australia/New Zealand 3/12/15 the 90th Blackpool Dance Festival (5/21/15-5/29/15) 16-day Yokohama (Tokyo) to Singapore 3/18/15 NYC to Southampton 5/10/15-5/17/15 and/or 8-Day Hong Kong to Singapore 3/26/15 (includes Vietnam, Cambodia & Thailand) Southampton to NYC 5/27/15-6/3/15 10-day Singapore to Dubai 4/3/15 5/17/15 10-day British Isles w/overnight in Liverpool 12-Day Fort Lauderdale to Southampton Transatlantic 4/21/15 for Cunard 175th Anniversary Celebration & Blackpool 25-day Cape Town to Sydney 1/27/16 2016 early MEDITERRANEAN MIX AND MATCH 10-day Hong Kong to Yokohama 3/10/16 booking deals expire ® 10-day Yokohama to Hong Kong 3/20/16 2/28/15 QUEEN VICTORIA 18-day Cape Town to Southampton 4/22/16 Combine 7-, 14-, 16-Day Cruises to Spain, Italy, France, ® Greece and the Black Sea (May- Nov. 2015/16) South Pacific QUEEN VICTORIA 19-Day San Francisco to Sydney 2/19/15 ROUND TRIP NEW YORK CRUISES 48-day roundtrip Los Angeles 2/17/15 QUEEN MARY 2® South America QUEEN MARY 2® Halifax and Boston 5-Day Getaway 7/30/15 15-day Rio de Janeiro to Valparaiso 2/2/16 7– or 14-Day Canada/New England 9/27/15 PANAMA CANAL (book early; some options wait-listed) (Double overnight in Quebec) ® 13-Day Caribbean 11/12/15 QUEEN ELIZABETH 1/18/15 18-day (or 15-day) New York (or Fort Lauderdale) to Los Angeles (or San Francisco) ® NORTHERN EUROPE QUEEN VICTORIA 2/2/15 15-day (or 17- day) Fort ® QUEEN ELIZABETH Lauderdale to LA (or San Francisco) or 4/6/15 15-day (or 19-day) Baltics 14-days 6/30/15 or 8/9/15 LA to Fort Lauderdale (or New York) or 1/22/16 16-day Fort Iceland 12-day 7/14/15 Lauderdale to San Francisco “Many 2015 cruises almost sold-out or wait-listed. -

Lancashire, Blackpool, and Blackburn with Darwen: Local Restrictions - GOV.UK GOV.UK

04/10/2020 Lancashire, Blackpool, and Blackburn with Darwen: local restrictions - GOV.UK GOV.UK 1. Home (https://www.gov.uk/) 2. Coronavirus (COVID-19) (https://www.gov.uk/coronavirus-taxon) Guidance Lancashire, Blackpool, and Blackburn with Darwen: local restrictions Find out what you can and cannot do if you live, work or travel in affected local areas. Published 22 August 2020 Last updated 2 October 2020 — see all updates From: Department of Health and Social Care (https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-of-health- and-social-care) Contents Affected local areas Business and venue closures Social contact restrictions Travel restrictions Shielding Team sport and physical activity Weddings and funerals Religious ceremonies and places of worship Going to work Financial support – furlough and self-isolation Childcare Schools and colleges (face coverings) Universities and higher education Moving home An outbreak of coronavirus (COVID-19) has been identified in parts of Lancashire, Blackpool, and Blackburn with Darwen. The government and relevant local authorities are acting together to control the spread of the virus. Restrictions apply to the specified areas below. Affected local areas Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council area, with additional guidance and support applying in the following wards: Audley & Queen’s Park https://www.gov.uk/guidance/north-west-england-local-restrictions 1/13 04/10/2020 Lancashire, Blackpool, and Blackburn with Darwen: local restrictions - GOV.UK Bastwell & Daisyfield Billinge & Beardwood Blackburn -

Address, Description and Date of Death of Deceased Names, Addresses and Descriptions of Persons

o Date before which I—* Name of Deceased Address, description and date of death of Names, addresses and descriptions of Persons to whom notices of claims are to be notices of claims o (Surname first) Deceased given and names, in parentheses, of Personal Representatives to be given WRIGHT, Nora Elizabeth 68F Parklands, Wotton-under-Edge, Glouces- J. W. Ward & Son, 52 Broad Street, Bristol BS1 2EP. (Keith George Barber 15th June 1983 tershire, Widow. 8th December 1982. and John William Edward Thatcher.) (264) NEWTON, John 38 Roseberry Road, Billingham, Cleveland, Willis & Harrison, 116 Queensway, Billingham, Cleveland, Solicitors. (John 15th June 1983 General Labourer, llth December 1982. Willis and Graham Foster Harrison.) (265) SKINNER, Barbara 7 Dursley Road, Shirehampton, Avon, Widow. Roberts & Co., 352 Gloucester Road, Bristol BS7 8TP. (James Robert Skinner 15th June 1983 Florence. 29th March 1983. and Una Agnes Skinner.) (266) HOWE, Richard Charles 3 Jubilee Terrace, Trull, Taunton, Somerset, Clarke Willmott and Clarke, 6 Hammet Street, Taunton TA1 1RG. (John 24th June 1983 Gardener (Retired). 23rd March 1983. Matthew Close and Michael Terrance Newport.) (105) ADAMS, Grace Ellen ... 43 The Green, Crossfield Avenue, Cowes, Isle James Eldridge & Sons, 17 Lind Street, Ryde, Isle of Wight PO33 2NS^ 30th June 1983 of Wight, Secretary (Solicitor) (Retired). Solicitors. (Sarah Ann McKendry and Francis McKendry.) (106) 28th March 1983. GREGSON, Iris 2 St. Georges Road, Wallasey, Merseyside, Percy Hughes & Roberts, 19 Hamilton. Square, Birkenhead, Merseyside L41 6AY_ 6th July 1983 Spinster, llth February 1983. (Gordon Harrison Nichol, Brian William Gregson Bird and Christopher John (107) Gregson Gray.) HADFIELD, Elsie Little Gatehouse, Outseats, Hathersage, Derby- Keeble Hawsons, Old Cathedral Vicarage, 7 St. -

Name of Deceased

O i—* Name of Deceased Names, addresses and descriptions of Persons to whom notices of claims are to be Date on or before which Address, description and date of death of Deceased notices of claim to be ON (Surname first) given and names, in parentheses, of Personal (Representatives given FENSOM, Sydney Walter The Cottage, Seaview Road, Peacehaven, Sussex, Barclays Bank Ltd., 37, King William Street, E.C.4 25th April, 1950 formerly of 55, Abbotshall Road, London, S.E.6, (332) Administrative Commandant of U.N.RjR.A. (formerly Garage Proprietor). 2nd January, 1950. WOOD, Joseph 16, Wheeler Street, (Lozells, Birmingham, Butcher. Thomas F. Walker, 109, Colmore Row, Birmingham J, Solicitor. (Joseph Henry 30th April, 1950 2nd September, 1949. Wood and Bernard Wood.) (333) KING, Samuel Isaac 230, Hagley Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham, Estate Win. 'Bache & Sons, 23, New 'Street, West Bromwioh, Solicitors, or Douglas Michael 24th April! 1950 Agent. 3rd February, 1944. King, 327, Hagley IRoad, Bdfeba&ton, Birmingham. (Sarah King, Derek Moss King! (334) and Cyril George King.) GINNS, George 70, Seagrave Road, Sileby, Leicestershire, Hosiery Stone & Co., 4, Welford Place, Leicester, Solicitors. (Mary Imelda Ginns) 25th April, 1950 Manufacturer. 10th October, 1949. (335) WATSON, Thomas Pearcy Amotherby, near Malton, Yorkshire, Grocer. 22nd Pearsons & 'Ward, Malton, Yorks, Solicitors. (Walter Watson and Herbert Watson) ... 24th April, 1950 October, 1949. (336) CHAbwiCit, Frances 30, St. Heliers Road, Blackpool, Widow. 3rd Roland W. Robinson Son & Co., 27, Burley Street, (Blackpool, Solicitors. (Madeline 30th April, 1950 January, 1950. Kaye.) (337) STEELE, Mary Ann 843, Anlaby Road, Kingston-upon-Hull, Widow. 13th (Ma-inprize, (Rignall1 & WhittwoTth, Yorkshire Insurance 'Buildings, Lowgate, Hull, 28th April, 1950 December, 1949. -

The Most Deprived LSOA, and of 32844Th the Least Deprived;

The English Indices of Deprivation 2015 Blackpool Position Report Introduction The 2015 English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) was released on 30th September 2015, updating the 2010 Index. It is made up of indicators covering 7 topics, or “domains”, which are weighted according to their perceived contribution towards deprivation as follows: Individual indicators within the index are subject to change depending on the availability of the data, but DCLG treats the different iterations of the index as comparable. The indices therefore show change over time in relative deprivation levels. The index ranks four different geographies: . Lower Super Output Areas (LSOAs) – these are units of geography smaller than Council wards and contain around 1500 residents. A rank of 1 indicates the most deprived LSOA, and of 32844th the least deprived; . Local Authority (LA) level, based on an aggregated version of the LSOA data, where a rank of 1 indicates the most deprived local authority area, and 326th indicates the least deprived; . LEP area (ranked from 1-39); . CCG area (ranked from 1-209). This report covers the headline LSOA level and LA level rankings. There are several ways of measuring deprivation in all of these types of area. Explanations of the different rankings are provided throughout the report. Indices of Deprivation 2015 - Corporate Development and Engagement Team Key Findings . All overall measures at the Local Authority level show Blackpool has become relatively more deprived since 2004; . The 2015 index ranks Blackpool as the most deprived of 326 Local Authority areas in England, based on both the average LSOA score and concentration of deprivation measures; . -

Report Template

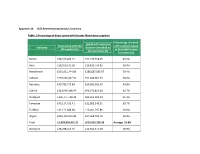

Appendix 3b CLES Benchmarking Analysis Summary Table 1:Percentage of direct spend with Greater Manchester suppliers Percentage of spend Spend with suppliers Total spend with top with suppliers based Authority based or branched in 30 suppliers (£) or branched in own own boundary (£) boundary (%) Bolton £68,330,289.71 £31,179,554.05 45.6% Bury £38,026,372.58 £10,810,750.81 28.4% Manchester £235,031,744.89 £186,687,585.67 79.4% Oldham £133,590,437.30 £91,644,381.53 68.6% Rochdale £70,793,775.84 £30,995,001.50 43.8% Salford £143,909,248.95 £90,276,813.00 62.7% Stockport £126,771,768.29 £82,563,092.39 65.1% Tameside £45,117,493.41 £22,863,548.01 50.7% Trafford £41,171,484.94 £15,062,797.86 36.6% Wigan £101,115,819.30 £57,568,701.76 56.9% Total £1,003,858,435.21 £619,652,226.58 Average 53.8% Blackpool £38,298,252.35 £14,912,671.29 38.9% Cheshire East £142,693,938.72 £56,321,917.66 39.5% Conclusion and Recommendations This final section of the report presents some concluding commentary on the analysis detailed in previous sections before proffering recommendations for the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities. Concluding commentary This research and report has sought to do two things in relation to a baseline position for the Greater Manchester Social Value Procurement Framework. First, it has sought to understand the extent to which the ten Greater Manchester authorities spend with suppliers based or with a branch in the Greater Manchester boundary (together with an understanding of Blackpool and Cheshire East Councils in their own respective boundaries). -

NAEST Operational and Management- MCA Approved Training Providers NAEST Operational Approved Training Providers

NAEST Operational and Management- MCA Approved Training Providers Training Providers: If you are an approved MCA course provider and not on this list or if your details need updating please email: [email protected]. If you hold pilot approval you will need to wait until full approval is granted by an MCA surveyor before being listed below. Seafarers: If you have undertaken or are about to undertake MCA approved training and it is not listed below, please email [email protected] to ensure it is MCA approved. NAEST Operational: Provided you undertook NAEST Operational (formally NARAS Operational) after 1 January 2005, you will have covered the use of Electronic Chart Display Information Systems (ECDIS) required by the STCW Code. If you have not covered the ECDIS requirements, you will need to complete a standalone MCA approved ECDIS course. NAEST Management: If you have not covered the ECDIS requirements, your NAEST Management course will be extended to include the ECDIS training required by the STCW Code. NAEST Operational Approved Training Providers Company Location Address Contact Details Website Blackpool and Fylde Fleetwood, Fleetwood Nautical Campus, Broadwater, Tel: 01253 779123 www.blackpool.ac.uk/nautical College Lancashire Fleetwood, Lancashire, FY7 8JZ Email: [email protected] City of Glasgow Glasgow, Scotland 21 Thistle Street, Glasgow, G5 9XB Tel: 01413 755572 www.cityofglasgowcollege.ac.uk College Email: [email protected] East Coast College Lowestoft, Suffolk St. Peter’s Street, Lowesoft, Suffolk, NR32 2NB Tel: 01502 525055 www.eastcoast.ac.uk Email: [email protected] Glasgow Maritime Glasgow, Scotland 101 Abercromby Business Centre, 279 Tel: 01415 542248 www.glasgowmaritimeacademy.