Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical Inspirations

Follow us on www.twitter.com/easterneye • www.easterneye.eu • September 21, 2012 Entertainment 23 By Pooja Chaudhary Watch: The latest By Gin and Rees movie from multi- Musical inspirations award-winning di- rector Madhur Our Bhandarkar is this week’s big Bollywood release Heroine, re- volving around the rise and fall of a top actress. Lead star Kareena Kapoor stars alongside Arjun Rampal and Ran- deep Hooda. Appreciate: Those who like literature or as- piring writers should head over to Asia House in London next Tuesday (25) for an evening with award-winning authors Kish- war Desai and Anjali Joseph. They will be discussing their second books and why they are driven to write about controversial sub- jects. Log onto www.asiahouse.org for more. Buy: One of the biggest classical music festi- vals of the year starts next Thursday (27) and runs until next Sunday (30). The Darbar Fes- tival in London will see established stars of the Indian classical music scene and up-and coming talents take to the stage for four days of incredible music, illuminating discussions and interesting demonstrations. You can buy tickets for individual events or can get a fes- tival pass. Visit www.southbankcentre.co.uk and www.darbar.org to find out more. Sing-along: There will be a chance to sing along to some of the biggest Bollywood hits of the past few years this weekend with su- FROM a young age, our parents and dhol players like Johnny Kalsi with our culture and our music. We bhangra. It was also an honour to per singers Mohit Chauhan and Shafqat used to take us to the temple for would always take our full atten- gained knowledge of our traditional take music lessons from Ustad Nir- Amanat Ali’s not-to-be-missed concerts. -

The Sikh Diaspora Global Diasporas Series Editor: Robin Cohen

The Sikh diaspora Global diasporas Series Editor: Robin Cohen The assumption that minorities and migrants will demonstrate an exclusive loyalty to the nation-state is now questionable. Scholars of nationalism, international migration and ethnic relations need new conceptual maps and fresh case studies to understand the growth of complex transnational identities. The old idea of “diaspora” may provide this framework. Though often conceived in terms of a catastrophic dispersion, widening the notion of diaspora to include trade, imperial, labour and cultural diaporas can provide a more nuanced understanding of the often positive relationships between migrants’ homelands and their places of work and settlement. This book forms part of an ambitious and interlinked series of volumes trying to capture the new relationships between home and abroad. Historians, political scientists, sociologists and anthropologists from a number of countries have collaborated on this forward-looking project. The series includes two books which provide the defining, comparative and synoptic aspects of diasporas. Further titles, of which The Sikh diaspora is the first, focus on particular communities, both traditionally recognized diasporas and those newer claimants who define their collective experiences and aspirations in terms of a diasporic identity. This series is associated with the Transnational Communities Programme at the University of Oxford funded by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council. Already published: Global diasporas: an introduction Robin Cohen New diasporas Nicholas Van Hear Forthcoming books include: The Italian labour diaspora Donna Gabaccia The Greek diaspora: from Odyssey to EU George Stubos The Japanese diaspora Michael Weiner, Roger Daniels, Hiroshi Komai The Sikh diaspora The search for statehood Darshan Singh Tatla © Darshan Singh Tatla 1999 This book is copyright under the Berne Convention. -

THE BAND Initially, It Was the Love of Bhangra and the Desire to Perform Live Music That Brought CMY Together This Group of Talented Friends

ENKARMA_MEDIA_lowquality.pdf 1 10-02-09 7:28 PM C M Y CM MY CY THE BAND Initially, it was the love of Bhangra and the desire to perform live music that brought CMY together this group of talented friends. In 2007, finding the need to flex their creative K muscle, En Karma began writing and recording their own style of Bhangra music. Now ready for the release of their debut album, and having vastly toured across North America and Europe,En Karma have embarked on a journey that has lead them to be the pioneers of Global Live Bhangra! They have accompanied and shared the stage with many famous North American and International artists such as Malkit Singh, Sam Roberts just mention a few. Solid musicianship, genuine friendship, and a collective vision have always remained the cornerstones of En Karma’s success. Since the beginning, En Karma has maintained creative control over their music by writing, playing, and producing all of the music themselves. In a few short years these talented musicians have established themselves in Vancouver’s growing global music scene, and have gained Hugh recognition across Europe and India. The music of En Karma captures the perfect balance of traditional Bhangra and contemporary fusion. Although there are elements of reggae, R&B, and rock n’ roll in En Karma’s music, they have remained firmly planted in their Bhangra roots. En Karma seems to especially strike a cord with their young South Asian fans. Audience members – who like the band members may have been born outside of India, will feel a connection with the music of Punjab when En Karma takes the stage (no matter where they were born). -

Gendering Dance

religions Article Gendering Dance Anjali Gera Roy Department of Humanities & Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, Kharagpur 721302, India; [email protected] Received: 27 January 2020; Accepted: 15 April 2020; Published: 18 April 2020 Abstract: Originating as a Punjabi male dance, bhangra, reinvented as a genre of music in the 1980s, reiterated religious, gender, and caste hierarchies at the discursive as well as the performative level. Although the strong feminine presence of trailblazing female DJs like Rani Kaur alias Radical Sista in bhangra parties in the 1990s challenged the gender division in Punjabi cultural production, it was the appearance of Taran Kaur Dhillon alias Hard Kaur on the bhangra rap scene nearly a decade and a half later that constituted the first serious questioning of male monopolist control over the production of Punjabi music. Although a number of talented female Punjabi musicians have made a mark on the bhangra and popular music sphere in the last decade or so, Punjabi sonic production continues to be dominated by male, Jat, Sikh singers and music producers. This paper will examine female bhangra producers’ invasion of the hegemonic male, Sikh, Jat space of bhangra music to argue that these female musicians interrogate bhangra’s generic sexism as well as the gendered segregation of Punjabi dance to appropriate dance as a means of female empowerment by focusing on the music videos of bhangra rapper Hard Kaur. Keywords: hypermasculinity; misogyny; sexism; good girl; bad girl; bhangra; rap; Hard Kaur 1. Introduction “Munde bhangra paunde te kudian giddha paawan [Boys dance to the steps of bhangra and girls to those of giddha],” Sukhbir’s chartbusting bhangra song of the 1990s, provides a glimpse into the segregated space of Punjabi dance with its generic gendered boundaries (Sukhbir 1996). -

![Aaja Nach Lai [Come Dance] Performing and Practicing Identity Among Punjabis in Canada Nicola Mooney](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3570/aaja-nach-lai-come-dance-performing-and-practicing-identity-among-punjabis-in-canada-nicola-mooney-9163570.webp)

Aaja Nach Lai [Come Dance] Performing and Practicing Identity Among Punjabis in Canada Nicola Mooney

Document generated on 09/29/2021 4:59 p.m. Ethnologies Aaja Nach Lai [Come Dance] Performing and Practicing Identity among Punjabis in Canada Nicola Mooney Danse au Canada Article abstract Dance in Canada This article discusses the performance of Punjabi folk dances bhangra and Volume 30, Number 1, 2008 giddha in some Canadian contexts. After introducing a notion of Punjabi identity, the article provides a brief description of these dance forms, their URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/018837ar agrarian origins and their gendered natures, as well as of the types of events at DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/018837ar which these dances are performed among Canadian Punjabis, and specifically, Jat Sikhs. I argue that not only do these dances express and maintain Punjabi identity in diasporic contexts, but that these identities refer to a Jat “rural See table of contents imaginary” that is actively constructed through dance and music in response to the displacement of urban and transnational migration. This rural imaginary is usurped by bhangra’s increasing Westernization and popularity in the non-Jat Publisher(s) South Asian diaspora, thus raising challenges to Jat centrality, meaning, and identity. Association Canadienne d'Ethnologie et de Folklore ISSN 1481-5974 (print) 1708-0401 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Mooney, N. (2008). Aaja Nach Lai [Come Dance]: Performing and Practicing Identity among Punjabis in Canada. Ethnologies, 30(1), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.7202/018837ar Tous droits réservés © Ethnologies, Université Laval, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. -

Bhangranation New Meanings of Punjabi Identity in the Twenty First Century

111 Anjali Roy: Bhangra Nation and Punjabi Identity BhangraNation New Meanings of Punjabi Identity in the Twenty First Century Anjali Gera Roy Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur ________________________________________________________________ Punjabi identity, punjabiyat, has been fissured several times by religious, linguistic and national boundaries in the last century or so. Historians, anthropologists and religious studies scholars have turned their attention in the recent years to recover the meaning of punjabiyat in the everyday lives of people. Their research has uncovered a shared Punjabi place differentiated by region, religion, and caste with porous, fluid, multiple boundaries. The construction of formal religious boundaries, reinforced by linguistic, resulted in their closure, which was completed through the division of Punjab in 1947. Even though a literal return to the shared Punjabi place might not be possible, ordinary Punjabis have resisted its reinscription and division through new cartographies by returning to the memory of the Undivided Punjabi place. Advanced travel and communication technologies have opened new possibilities of contact between dispersed Punjabi groups enabling virtual, if not real, reconstructions of punjabiyat in cyberspace. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Those of you who do not belong to my generation will live to see Punjab’s identity overcome the effects of the religious divide of 1947 and enjoy the fruit of a prosperous and happy Punjab which transcends the limitation of a geographical map. (Khizar Hayat Tiwana, Minister of the Punjab Union 1947, in 19641) Several attempts to carve out a distinctive Punjabi identity have been made before and after the 1947 Partition, including ethno-linguistic constructions such as Azad Punjab and Punjabi suba movements or ethno-religious ones such as the movement for Khalistan or the Sikh Nation. -

![Aaja Nach Lai [Come Dance]: Performing and Practicing Identity Among Punjabis in Canada"](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2354/aaja-nach-lai-come-dance-performing-and-practicing-identity-among-punjabis-in-canada-9942354.webp)

Aaja Nach Lai [Come Dance]: Performing and Practicing Identity Among Punjabis in Canada"

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Érudit Article "Aaja Nach Lai [Come Dance]: Performing and Practicing Identity among Punjabis in Canada" Nicola Mooney Ethnologies, vol. 30, n° 1, 2008, p. 103-124. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/018837ar DOI: 10.7202/018837ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 10 février 2017 06:23 AAJA NACH LAI [COME DANCE] Performing and Practicing Identity among Punjabis in Canada Nicola Mooney University of the Fraser Valley At Arjun’s tenth birthday, celebrated in high style at a banquet hall, his elder female relatives put on an energetic giddha performance. Running around with his cousins in the hall’s forecourt, he apparently wasn’t that enthralled by their dancing, but his father and uncles seemed to enjoy seeing their wives and sisters-in-law in this traditional guise. -

The Heritage of British Bhangra: Popular Music Heritage, Cultural Memory, and Cultural Identity

The Heritage of British Bhangra: Popular music heritage, cultural memory, and cultural identity. Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Gurdeep John Singh Khabra. September 2014. In memory of Charan Singh & Nasib Kaur. Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Ethnography ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Music Analysis .................................................................................................................................. 13 Reflexivity and Ethics ....................................................................................................................... 17 Chapter 1: Contextualising British Bhangra music heritage ................................................................. 20 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 20 Defining BrAsian ............................................................................................................................. -

'Essence' of Bhangra Through Panjabi

University of Huddersfield Repository Sahota, Hardeep The Search for the ‘Essence’ of Bhangra through Panjabi heritage Original Citation Sahota, Hardeep (2011) The Search for the ‘Essence’ of Bhangra through Panjabi heritage. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/17518/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ The Search for the ‘Essence’ of Bhangra through Panjabi heritage. Hardeep Singh Sahota A portfolio consisting of a performance DVD, a hardcopy of an interactive timeline and Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Research. University of Huddersfield 2011 Abstract This research examines the concept of Bhangra from my perspective as a practitioner and supported by ethnographic research. -

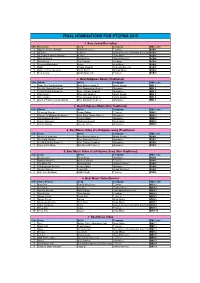

Final Nominations for Ptcpma 2015

FINAL NOMINATIONS FOR PTCPMA 2015 1. Best Sound Recording S.No Recordist Song Company SMS code 1 Dipesh Sharma Batalwi Mitti Di Khushboo T Series BSR 1 2 Dr Zeus Judaa 2 Speed Records & Rhythm Boyz Ent BSR 2 3 Gurjinder & Akash Bambar Ik Saal Sony Music BSR 3 4 Nick Dhammu Patiala Peg Speed Records BSR 4 5 Pav Dharia Teri Yaadan Lokdhun BSR 5 6 Praveen Muralidhar Naina Zee Music BSR 6 7 PBN Phatte Chuk Di Vvanjhali Records BSR 7 8 Sameer Charegaonkar Kamli Ramli Wadali Music BSR 8 9 Tom Lowry Singh Naal Jodi T Series BSR 9 2. Best Religious Album (Traditional) S.No. Album Artist Company SMS code 1 Deen Duni Da Paatshah Bhai Baldev Singh Ji Amritt Saagar BRL 1 2 Gur Ka Shabad Pachaan Bhai Gagandeep Singh Ji Shemaroo BRL 2 3 Ke Datta Maha Daan Ho Bhai Tajinder Singh Ji Shemaroo BRL 3 4 Main Naahi Bhai Lalit Singh Ji Amritt Saagar BRL 4 5 Meri Patian Bhai Jaskaran Singh Ji Amritt Saagar BRL 5 6 Santho Prabhmerasda Dayala Bhai Amarjeet Singh Ji Shemaroo BRL 6 3. Best Religious Album (Non Traditional) S.No. Album Artist Company SMS code 1 Gurmukh Pyareo Geeta Zaildar T Series BNR 1 2 Saiyan Tu Mukhda Na Modien Sant Baba Piaara Singh Ji Shemaroo BNR 2 3 Sahibzadean Da Viah Inderjit Nikku Shemaroo BNR 3 4 Singh Shaheed Ravinder Grewal Amar Audio BNR 4 5 Singh Saviour Various Artists Shemaroo BNR 5 4. Best Music Video of a Religious Song (Traditional) S.No. Song Artist Company SMS code 1 Bhale Se Vanjarey Bhai Baldev Singh Ji Amritt Saagar BVR 1 2 Gur Hath Dhariyo Bhai Gurpreet Singh Ji Shemaroo BVR 2 3 Ke Datta Maha Daan Ho Bhai Tajinder Singh Ji Shemaroo BVR 3 4 Sach Sahib Mera Bibi Arvind Pal Kaur Ji Shemaroo BVR 4 5.