Becoming Sonny Rollins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 11/09/2011 04:57 Pm

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 11/09/2011 04:57 pm WNCU 90.7 FM Format: Jazz North Carolina Central University (Raleigh - Durham, NC) This Period (TP) = 11/02/2011 to 11/08/2011 Last Period (TP) = 10/25/2011 to 11/01/2011 TP LP Artist Album Label Album TP LP +/- Rank Rank Year Plays Plays 1 2 Jeff McLaughlin Quartet Blocks Owl Studios 2011 11 12 -1 2 27 Christian McBride Big The Good Feeling Mack Avenue 2011 9 3 6 Band 3 308 Pat Martino Undeniable: Live At Blues HighNote 2011 8 0 8 Alley 4 4 Dr. Michael White Adventures In New Basin Street 2011 7 9 -2 Orleans Jazz Pt. 1 4 8 Stefon Harris, David Ninety Miles Concord Picante 2011 7 8 -1 Sanchez, Christian Scott 4 14 Warren Wolf Warren Wolf Mack Avenue 2011 7 6 1 4 308 Houston Person So Nice HighNote 2011 7 0 7 8 4 Jay Ashby & Steve Davis Mistaken Identity MCG Jazz 2011 6 9 -3 8 10 Orrin Evans Freedom Posi-Tone 2011 6 7 -1 10 1 Roy Haynes Roy-Alty Dreyfus 2011 5 13 -8 10 3 Cedar Walton The Bouncer High Note 2011 5 10 -5 10 8 Afro Bop Alliance Una Mas OA2 2011 5 8 -3 10 20 Alan Leatherman Detour Ahead AJL 2011 5 4 1 10 20 Dave Valentin Pure Imagination HighNote 2011 5 4 1 10 43 Sir Roland Hanna Colors From A Giant's Kit IPO 2011 5 2 3 10 43 Denise Donatelli What Lies Within Savant 2008 5 2 3 17 4 Bill O'Connell Triple Play Plus Three Zoho 2011 4 9 -5 17 10 John Stein Hi Fly Whaling City Sound 2011 4 7 -3 17 18 Gerald Beckett Standard Flute Summit 2011 4 5 -1 17 20 Denise Donatelli When Lights Are Low Savant 2010 4 4 0 17 27 Sammy Figueroa Urban Nature -

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": an Analytical Approach to Jazz

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": An Analytical Approach to Jazz Styles and Influences Nicholas Vincent DiSalvio Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation DiSalvio, Nicholas Vincent, "Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": An Analytical Approach to Jazz Styles and Influences" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. CHARLES RUGGIERO’S “TENOR ATTITUDES”: AN ANALYTICAL APPROACH TO JAZZ STYLES AND INFLUENCES A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Nicholas Vincent DiSalvio B.M., Rowan University, 2009 M.M., Illinois State University, 2013 May 2016 For my wife Pagean: without you, I could not be where I am today. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my committee for their patience, wisdom, and guidance throughout the writing and revising of this document. I extend my heartfelt thanks to Dr. Griffin Campbell and Dr. Willis Delony for their tireless work with and belief in me over the past three years, as well as past professors Dr. -

![Eric Dolphy Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6248/eric-dolphy-collection-finding-aid-library-of-congress-226248.webp)

Eric Dolphy Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Eric Dolphy Collection Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2014 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu014006 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2014565637 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Collection Summary Title: Eric Dolphy Collection Span Dates: 1939-1964 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1960-1964) Call No.: ML31.D67 Creator: Dolphy, Eric Extent: Approximately 250 items ; 6 containers ; 5.0 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Eric Dolphy was an American jazz alto saxophonist, flautist, and bass clarinetist. The collection consists of manuscript scores, sketches, parts, and lead sheets for works composed by Dolphy and others. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Dolphy, Eric--Manuscripts. Dolphy, Eric. Dolphy, Eric. Dolphy, Eric. Works. Selections. Mingus, Charles, 1922-1979. Works. Selections. Schuller, Gunther. Works. Selections. Subjects Composers--United States. Jazz musicians--United States. Jazz--Lead sheets. Jazz. Music--Manuscripts--United States. Saxophonists--United States. Form/Genre Scores. Administrative Information Provenance Gift, James Newton, 2014. Accruals No further accruals are expected. Processing History The Eric Dolphy Collection was processed by Thomas Barrick in 2014. Thomas Barrick coded the finding aid for EAD format in October 2014. -

BROWNIE the Complete Emarcy Recordings of Clifford Brown Including Newly Discovered Essential Material from the Legendary Clifford Brown – Max Roach Quintet

BROWNIE The Complete Emarcy Recordings of Clifford Brown Including Newly Discovered Essential Material from the Legendary Clifford Brown – Max Roach Quintet Dan Morgenstern Grammy Award for Best Album Notes 1990 Disc 1 1. DELILAH 8:04 Clifford Brown-Max RoaCh Quintet: (V. Young) Clifford Brown (tp), Harold Land (ts), Richie 2. DARN THAT DREAM 4:02 Powell (p), George Morrow (b), Max RoaCh (De Lange - V. Heusen) (ds) 3. PARISIAN THOROUGHFARE 7:16 (B. Powell) 4. JORDU 7:43 (D. Jordan) 5. SWEET CLIFFORD 6:40 (C. Brown) 6. SWEET CLIFFORD (CLIFFORD’S FANTASY)* 1:45 1~3: Los Angeles, August 2, 1954 (C. Brown) 7. I DON’T STAND A GHOST OF A CHANCE* 3:03 4~8: Los Angeles, August 3, 1954 (Crosby - Washington - Young) 8. I DON’ T STAND A GHOST OF A CHANC E 7:19 9~12: Los Angeles, August 5, 1954 (Crosby - Washington - Young) 9. STOMPIN’ AT TH E SAVOY 6:24 (Goodman - Sampson - Razaf - Webb) 10. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU 7:36 (C. Porter) 11. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU* 8:29 * Previously released alternate take (C. Porter) 12. I’ LL STRING ALONG WITH YOU 4:10 (Warren - Dubin) Disc 2 1. JOY SPRING* 6:44 (C. Brown) Clifford Brown-Max RoaCh Quintet: 2. JOY SPRING 6:49 (C. Brown) Clifford Brown (tp), Harold Land (ts), Richie 3. MILDAMA* 3:33 (M. Roach) Powell (p), George Morrow (b), Max RoaCh (ds) 4. MILDAMA* 3:22 (M. Roach) Los Angeles, August 6, 1954 5. MILDAMA* 3:55 (M. Roach) 6. -

Relatório De Músicas Veiculadas

Relatório de Programação Musical Razão Social: Fundação de Ensino e Tecnologia de Alfenas CNPJ: 17878554001160 Nome Fantasia: Rádio Universidade FM Dial: 106,7 Cidade: Alfenas UF: MG Execução Data Hora Descrição Intérprete Compositor Gravadora Ao Vivo Mecânico 01/12/2017 00:01:25 Fechamento da Emissora CAMILO ZAPONI X 01/12/2017 07:00:00 Hino Nacional Brasileiro ABERTURA Francisco Manuel da Silva e Osório Duque X Estrada 01/12/2017 07:03:33 Abertura da Emissora CAMILO ZAPONI X 01/12/2017 07:04:51 Prefixo Reinaldo Amâncio X 01/12/2017 07:05:26 Carinhoso CAMILO ZAPONI X 01/12/2017 07:05:46 Sofres Porque Queres Altamiro Carrilho Pixinguinha e Benedito Lacerda Movie Play X 01/12/2017 07:09:04 Lamentos Altamiro Carrilho Pixinguinha e Vinícius de Moraes Movie Play X 01/12/2017 07:12:22 Na Cadência do Samba Waldir Azevedo Ataulfo Alves e Paulo Gesta Continental X 01/12/2017 07:15:00 Camondongo Waldir Azevedo Waldir Azevedo e Moacyr M. Gomes Continental X 01/12/2017 07:17:19 O Violão da Viola do Cerrado Carrapa do Cavaquinho e a Cia de Música Carrapa do Cavaquinho Zen Records X 01/12/2017 07:20:19 Dobradinha Brasileira Carrapa do Cavaquinho e a Cia de Música Carrapa do Cavaquinho Zen Records X 01/12/2017 07:22:25 Nunca Benedito Costa e Seu Conjunto Lupicínio Rodrigues Brasidisc X 01/12/2017 07:25:08 Pedacinhos do Céu Benedito Costa e Seu Conjunto Waldir Azevedo Brasidisc X 01/12/2017 07:28:15 Levanta Poeira Orlando Silveira Zequinha de Abreu EMI X 01/12/2017 07:30:50 Sururu na Cidade Orlando Silveira Zequinha de Abreu EMI X 01/12/2017 07:33:37 -

Top 10 Albums Rhythm Section Players Should Listen to 1

Top 10 Albums Rhythm Section Players Should Listen To 1. Money Jungle by Duke Ellington Duke Ellington-Piano Charles Mingus-Bass Max Roach-Drums RELEASED IN 1963 Favorite Track: Caravan 2. Monk Plays Duke by Thelonious Monk Thelonious Monk- Piano Oscar Pettiford-Bass Kenny Clarke-Drums RELEASED IN 1956 Favorite Track: I Let A Song Out of My Heart 3. We Get Request by Oscar Peterson Trio Oscar Peterson-Piano Ray Brown-Bass Ed Thigpen-Drums RELEASED IN 1964 Favorite Track: Girl from Ipanema 4. Now He Sings, Now He Sobs by Chick Corea Chick Corea-Piano Miroslav Vitous-Bass Roy Haynes-Drums RELEASED IN 1968 Favorite Track: Matrix 5. We Three by Roy Haynes Phineas Newborn-Piano Paul Chambers-Bass Roy Haynes-Drums RELEASED IN 1958 Favorite Track(s): Sugar Ray & Reflections 6. Soul Station by Hank Mobley Hank Mobley-Tenor Sax Wynton Kelly-Piano Paul Chambers-Bass Art Blakey-Drums RELEASED IN 1960 Favorite Track: THE ENTIRE ALBUM! 7. Free for All by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Freddie Hubbard-Trumpet Curtis Fuller-Trombone Wayne Shorter-Tenor Saxophone Cedar Walton-Piano Reggie Workman-Bass Art Blakey-Drums RELEASED IN 1964 Favorite Track: THE ENTIRE ALBUM 8. Live at the IT Club by Thelonious Monk Charlie Rouse-Alto Saxophone Thelonious Monk-Piano Larry Gales-Bass Ben Riley-Drums RECORDED IN 1964; RELEASED IN 1988 Favorite Track: THE ENTIRE ALBUM 9. Clifford Brown & Max Roach by Clifford Brown & Max Roach Clifford Brown-Trumpet Harold Land-Tenor Saxophone Richie Powell-Piano George Morrow-Bass Max Roach-Drums RELEASED IN 1954 Favorite Track(s): Jordu, Daahoud, and Joy Spring 10. -

Jazzpress 0615

CZERWIEC 2015 Gazeta internetowa poświęcona muzyce improwizowanej ISSN 2084-3143 ISSN TOP NOTE PeGaPoFo – Świeżość REAKTYWACJA! Bartłomiej Rozmowy: Oleś Piotr Schmidt Jestem uzależniony Asia Czajkowska-Zoń od brzmienia Charles Gayle Majerczyk Kuba fot. Oleś, Bartłomiej dziękujemy! < Od Redakcji Udało się! Reaktywacja RadioJAZZ.FM stała się faktem – a wszystko dzięki Wam! Zorga- nizowana na portalu Wspieram.to zbiórka społecznościowa zakończyła się sukcesem. Zebraliśmy ponad dwa razy więcej pieniędzy, niż przewidywaliśmy, co umożliwi nam lepszy start oraz zapewni stabilne działanie! Jesteśmy teraz w stu procentach pewni, że już niedługo będziemy mogli ruszyć z nadawaniem muzyki – planujemy start na wrze- sień bieżącego roku. Teraz przed nami sporo pracy, aby przygotować sprzęt do naszych jazzowych potrzeb, stworzyć elegancką i przejrzystą stronę internetową oraz aplikację, dzięki której każdy będzie mógł słuchać prezentowanej przez nas muzyki przez komór- kę – na spacerze, na wyjeździe, w komunikacji miejskiej czy w samochodzie. Dziękujemy Wam, drodzy słuchacze RadioJAZZ.FM i czytelnicy JazzPRESSu. To dzię- ki Waszemu zaangażowaniu i Waszym wpłatom nasza akcja się powiodła, a my bę- dziemy mogli z pełną mocą ruszyć i dumnie działać jako jedyne w Polsce radio jazzo- we! Dziękujemy także wszystkim tym, którzy tak pięknie bawili się hasłem #jazzdoit i przysyłali do nas pomysłowe zdjęcia. Z tego miejsca chcemy podziękować także wszystkim naszym ambasadorom oraz przyjaciołom, którzy mają jazz w sercu i pomogli nam rozpowszechnić informację -

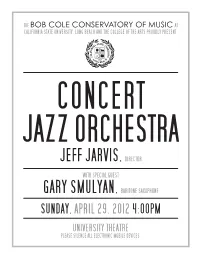

Jeff Jarvis,Director

CONCERT JAZZ ORCHESTRA JEFF JARVIS, DIRECTOR WITH SPECIAL GUEST GARY SMULYAN, BARITONE SAXOPHONE SUNDAY, APRIL 29, 2012 4:00PM UNIVERSITY THEATRE PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. TONIGHT’S PROGRAM GENTLY / Bob Mintzer This well-crafted original is the title track of a recording of the Bob Mintzer Big Band. This recording project was unique in that the horn section stood in a circle surrounding a specially designed ribbon microphone that was extremely sensitive and accurate. This microphone would not accept loud dynamic levels, so Bob Mintzer wrote material that showcased the band playing at softer dynamics, which resulted in frequent use of muted brass, flugelhorns, and woodwinds. Today’s soloists include Josh Andree (tenor sax) and Will Brahm (guitar). THEN AND NOW / George Stone This terrific original composition and arrangement is featured on a recent recording of the George Stone Big Band entitled “The Real Deal”, performed by a collection of Southern California’s finest studio musicians. George’s music is frequently featured at our concerts because of its superior quality, both from a compositional standpoint and also in terms of orchestration. This piece has it all—melodic integrity, intense rhythms, lush harmonies, and sufficient solo space. Today’s soloists include Eun young Koh (piano), Josh Andree (tenor sax), Will Brahm (guitar), and Daniel Hutton (alto sax). CHINA BLUE / Jeff Jarvis Originally composed as a commission for a big band in Williamsburg VA, the work features a winding trumpet melody supported by muted trombone parts, warm flugelhorn lines, and beautiful woodwind parts played by the saxophone section. The piece proves challenging since the musicians are faced with executing exposed parts with delicacy and restraint.