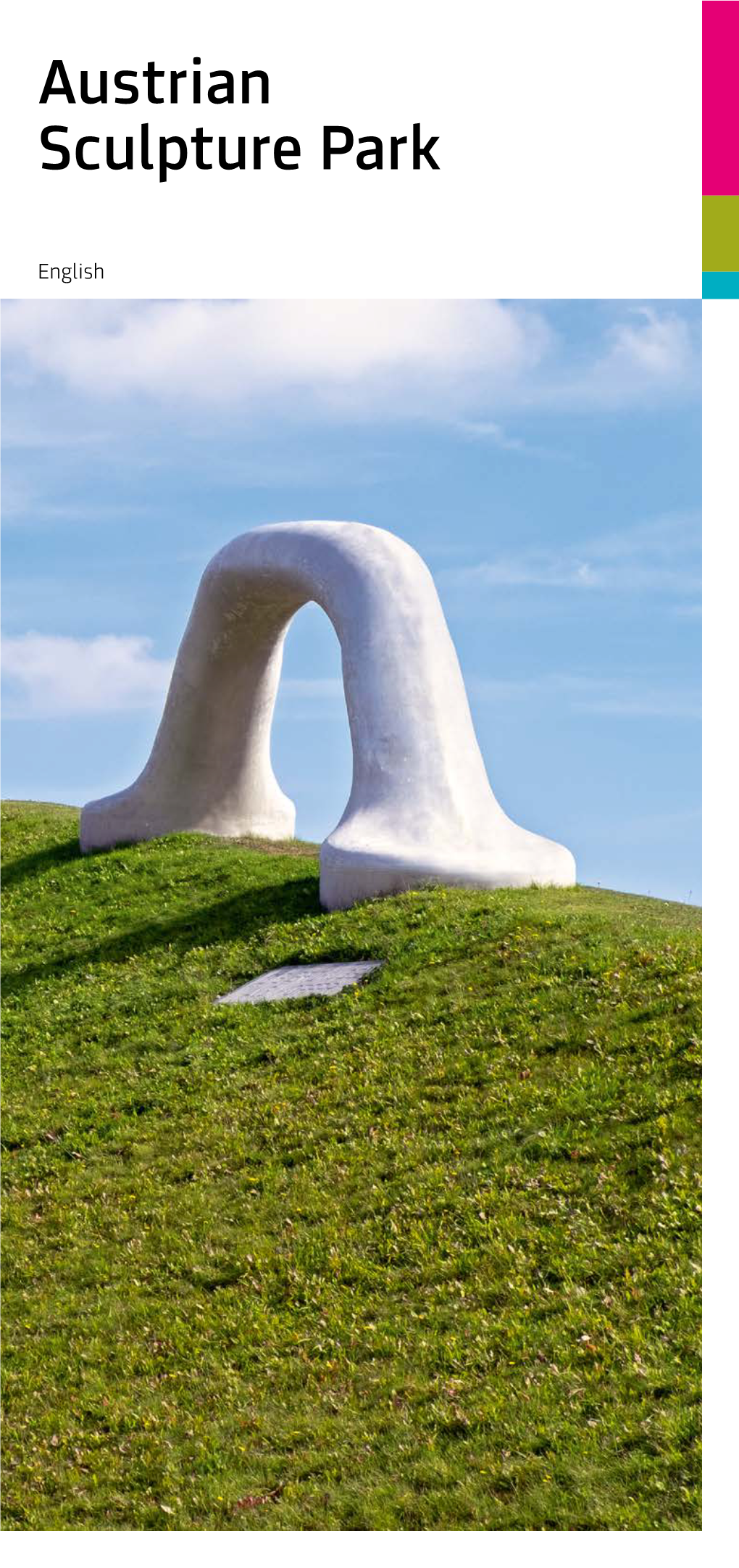

Austrian Sculpture Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kunst Nach 1945 Kunst Nach 1945

kunst nach 1945 kunst nach 1945 Wir laden Sie herzlich zu unserer Verkaufsausstellung vom 9. Mai bis 30. Juni 2018 in die Galerie ein. We cordially invite you to our sales exhibition from 9 May to 30 June 2018 at the gallery. Wir freuen uns auf Ihren Besuch. We are looking forward to your visit. Katharina Zetter-Karner und and Christa Zetter Lobkowitzplatz 1, A-1010 Wien Mo-Fr 10-18 Uhr, Sa 11-14 Uhr T +43/1/513 14 16, F +43/1/513 76 74 [email protected] www.galerie-albertina.at Dieser Katalog erscheint anlässlich der gleichnamigen Ausstellung Herausgeber und Eigentümer: Galerie bei der Albertina · Zetter; Redaktion: Katharina Zetter-Karner, Christa Zetter Texte: Monika Girtler, Sophie Höfer, Maximilian Matuschka, Andrea Schuster, Sophie Weissensteiner Lektorat: Andrea Schuster, Katharina Zetter-Karner; Grafik-Design: Maria Anna Friedl Fotos: Graphisches Atelier Neumann, Wien; Lithografie und Druck: Graphisches Atelier Neumann, Wien © Galerie bei der Albertina · Zetter GmbH, 2018 / Angaben ohne Gewähr v.l.n.r.: Sophie Höfer, Maximilian Matuschka, Katharina Zetter-Karner, Sophie Weissensteiner, Christa Zetter, Andrea Schuster, Monika Girtler Index Attersee Christian Ludwig S. 38 Francis Sam S. 30 Moswitzer Gerhardt S. 102 Avramidis Annemarie S. 72 Freist Greta S. 54-57 Nakajima Osamu S. 108 Avramidis Joannis S. 24 Fronius Hans S. 12-13 Pakosta Florentina S. 84-85 Bäumer Eduard S. 40-43 Gironcoli Bruno S. 86-87 Pichler Traudel S. 68-71 Berger-Maringer Lotte S. 46 Goeschl Roland S. 26-29 Pillhofer Josef S. 20, 32-33 Bertoni Wander S. 8-11 Gruber Gerda S. -

Pressetext Comunicato Stampa.Pdf

Pressetext | Comunicato Stampa JOANNIS AVRAMIDIS 13.07.-20.10.2019 Eröffnung: 12.07.2019 Das Stadtmuseum Bruneck zeigt vom 13. Juli bis zum 20. Oktober 2019 eine Sonderausstellung über den großen Bildhauer Joannis Avramidis (1922-2016). Mit seinen formal strengen, gleichwohl facettenreichen Arbeiten zählt der Künstler Joannis Avramidis zusammen mit Fritz Wotruba zu den Protagonisten der österreichischen Bildhauerei nach 1945. Sein Werk kreist stets um die menschliche Figur als Einzelwesen und soziales Wesen und ist von der Vorstellung eines idealistischen Menschenbildes bestimmt. Joannis Avramidis wird 1922 im russischen Batumi am Schwarzen Meer als Sohn griechischer Einwanderer geboren. 1939 muss er seine Heimat verlassen, da sein Vater im Zuge der stalinistischen Verfolgungen ethnischer Minderheiten 1937 inhaftiert wird und in der Folge umkommt. Von 1939-1943 lebt er mit der Mutter und seinen Geschwistern in Athen, wo der junge Kunststudent mit Gelegenheitsarbeiten für den Unterhalt der Familie sorgt. 1943 wird er, wie viele junge Griechen, von den Nationalsozialisten als Zwangsarbeiter nach Wien verschleppt, wo er bis 1945 in den „Eisenbahnausbesserungswerken Kledering“ Stahlräder für Züge reparieren muss. Nach der Befreiung wird er sofort von den Sowjets als Spion verhaftet und in ein Internierungslager bei Budapest deportiert. Von dort gelingt es ihm zu entkommen und er kehrt nach Wien zurück, wo er an der Akademie der bildenden Künste das Studium der Malerei aufnimmt. Nach dessen Abschluss schreibt er sich in die Klasse für Restauratoren ein und von 1953 bis 1957 besucht er die sagenhafte Bildhauerklasse von Fritz Wotruba. Seinen internationalen Durchbruch hat Avramidis 1962 als er Österreich bei der XXXI. Biennale in Venedig vertritt. -

Joannis Avramidis Metamorphose

JOANNIS AVRAMIDIS METAMORPHOSE 1 JOANNIS AVRAMIDIS METAMORPHOSE MENSCH-BAUM HYBRIDE FIGUR Wir laden Sie herzlich zu unserer Verkaufsausstellung vom 15. März bis 28. April 2018 in die Galerie ein. We cordially invite you to our sales exhibition from 15 March to 28 April 2018 at the gallery. Wir freuen uns auf Ihren Besuch. We are looking forward to your visit. Katharina Zetter-Karner und and Christa Zetter Lobkowitzplatz 1, A-1010 Wien Mo-Fr 10-18 Uhr, Sa 11-14 Uhr T +43/1/513 14 16, F +43/1/513 76 74 www.galerie-albertina.at [email protected] 2 JOANNIS AVRAMIDIS 1958 1992 JOANNIS AVRAMIDIS 1958 1992 Kurzbiografie Österreichischer Förderpreis für Emeritierung Biography Austrian sponsorship award for sculpture Emeritus Bildhauerei 1922 1997 1922 1961 1997 Am 26. September im russischen 1961 Umfangreiche Schenkung von Werken an Born in Batumi on the coast of the Black City of Vienna sponsorship award; Large donation of works to the National Batum am Schwarzen Meer als Sohn Förderpreis der Stadt Wien; Hugo-von- die Nationalgalerie Athen Sea on September 26th to Greek parents, Hugo-von-Montfort prize, Bregenz Gallery of Athens Montfort-Preis, Bregenz griechischer Eltern geboren, die wegen 1998 who fled from Turkey to Russia due to the Prize of the Federation of Austrian Industry 1998 der Unterdrückung von Minderheiten aus Preis der Föderation der österreichischen suppression of minorities Korrespondierendes Mitglied der 1962 Corresponding member of the Academy der Türkei nach Russland geflohen sind Industrie Akademie der Künste Athen 1937 Participates in the Venice Biennale; of Athens 1962 1937 2000 His father becomes a victim of Stalin’s exhibition with Friedensreich Hundert- 2000 Teilnahme an der Biennale in Venedig: Der Vater wird Opfer der ethnischen Korrespondierendes Mitglied der ethnical purifications and dies in prison wasser at the Austrian pavilion. -

Mobile Learning / Fritz Wotruba Fritz Wotruba

mobile learning / fritz wotruba Fritz Wotruba. Hart im Nehmen Fritz Wotruba in seinem Wiener Atelier, 1947/48, © Belvedere, Wien, Dauerleihgabe der Fritz Wotruba Privatstiftung Lerne den Bildhauer Fritz Wotruba (1907–1975) persönlich kennen. Fritz Wotruba war Bildhauer. Ein Bildhauer, der keiner Mode folgte, sondern eigenen persönlichen und künstlerischen Überzeugungen. Es war ihm wichtig, mit ursprünglichen Materialien zu arbei- ten, diese authentisch zu behandeln, um Wahrhaftiges zu schaffen. Der Stein, dessen Härte und Widerstand, war für ihn die ultimative Herausforderung. Geboren und aufgewachsen in Wien, machte er hier auch seine Ausbildung zum Graveur und startete seine Laufbahn als Bildhauer. In einem großen Bekanntenkreis fand Wotruba Freunde und Unterstützer. 1938 musste er Österreich verlassen und mit seiner jüdischen Frau in die Schweiz fliehen. Nach dem Ende des Krieges kehrte er nach Wien zurück, um an der Akademie der bilden- den Künste eine Meisterklasse für Bildhauerei aufzubauen. Wotruba beteiligte sich auf vielfältige Weise am kulturellen Wiederaufbau Österreichs. An der Akademie setzte er sich für eine gute Ausbildung des künstlerischen Nachwuchses ein. Fritz Wotruba arbeitete unermüdlich an seinem eigenen künstlerischen Werk. Er war an vielen Ausstellungen im In- und Ausland beteiligt und übernahm öffentliche und private Aufträge. Dazu zählen beispielsweise die Ausführung eines Figurenreliefs für den Österreichischen Ausstel- lungspavillon 1958 in Brüssel oder die Gestaltung der Kirche zur Heiligsten Dreifaltigkeit in Wien- Mauer, besser bekannt als Wotrubakirche. Der künstlerische und schriftliche Nachlass von Fritz Wotruba ist seit Herbst 2011 im 21er Haus untergebracht. Weiterführende Links http://www.wien.gv.at/kultur/kulturgut/kunstwerke/ mobile learning / fritz wotruba Fritz Wotruba. Hart im Nehmen Diskussion & Aktivitäten Arbeitsblatt 1 Am Beginn die Zeichnung Fritz Wotruba bekam im Schulalter Stifte geschenkt und begann, damit zu zeichnen. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Ulrike Truger. Eine österreichische Bildhauerin im öffentlichen Raum“ Verfasserin Karoline Riebler angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. A 315 Studienblatt: Studienrichtung lt. Diplomstudium Kunstgeschichte Studienblatt: Betreuerin / Betreuer: HR Univ.-Doz. Dr. Werner Kitlitschka Danksagung Hiermit möchte ich mich bei allen Menschen bedanken, die mich bei der Erstellung meiner Diplomarbeit unterstützt haben: In erster Linie möchte ich mich sehr herzlich bei der Künstlerin Ulrike Truger selbst bedanken, welche mich hilfsbereit mit wichtiger Literatur und Bildmaterial versorgte. Sie nahm sich viel Zeit, um mit großer Offenheit meine zahlreichen Fragen zu beantworten. Ich bedanke mich ganz besonders bei meinem Betreuer, Herrn Doz. Dr. Werner Kitlitschka, welcher mich bereits bei der Themenfindung freundlich unterstütze, insbesondere für sein konstruktives Feedback. Mein besonderer Dank gilt meiner Familie, vor allem meinen Eltern Eva und Manfred Riebler, welche mir das Studium erst ermöglicht und mich während der gesamten Studienzeit stets in jeglicher Hinsicht gefördert haben. Meiner Mutter und Mag. Johannes Schmid möchte ich darüber hinaus für ihre orthographische Korrekturlesung danken. Auch meinem Freund Florian Harm möchte ich an dieser Stelle meine herzliche Dankbarkeit für seine Unterstützung und Hilfestellungen aussprechen. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung ................................................................................................. -

Skulpturen in Bad Homburg Und Frankfurt Rheinmain

Bad Homburg – Bad Vilbel – Burg Eppstein – Eschborn – Frankfurt – Hessenpark – Kloster Eberbach – Kronberg 21. Mai – 1. Okt. 2017 Skulpturen in Bad Homburg und Frankfurt RheinMain in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Museum Liaunig, Neuhaus, Österreich Eröffnung / Opening Reception Sonntag / Sunday, 21.05.2017, 11.30 Uhr / a.m. Schmuckplatz [gegenüber / opposite Kaiser-Friedrich-Promenade 55] 61348 Bad Homburg v.d.Höhe Begrüßung / Greeting Alexander W. Hetjes Oberbürgermeister / Mayor of Bad Homburg v.d.Höhe Axel Wintermeyer Staatsminister, Chef der Hessischen Staatskanzlei / Minister of State, Head of the State Chancellery of Hessen Stefan Quandt „Blickachsen“-Förderer, Vorsitzender des Kuratoriums der Stiftung Blickachsen / Blickachsen supporter, Chairman of the Blickachsen Foundation Board of Trustees Christian K. Scheffel Geschäftsführer der Stiftung Blickachsen / Managing Director of the Blickachsen Foundation Gründer und Kurator der „Blickachsen“ / Founder and curator of Blickachsen Einführung / Introduction Dr. Maria Schneider Ko-Kuratorin / Co-curator Veranstalter / Organizers Stiftung Blickachsen gGmbH Magistrat der Stadt Bad Homburg v.d.Höhe Kur- und Kongreß-GmbH Verwaltung der Staatlichen Schlösser und Gärten Hessen in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Museum Liaunig, Neuhaus, Österreich / in collaboration with Museum Liaunig, Neuhaus, Austria HESSEN unter der Schirmherrschaft des Hessischen Ministerpräsidenten Volker Bouffier / under the patronage of the Prime Minister of the State of Hessen, Volker Bouffier 21 May – 1 October 2017 BLICKACHSEN 11 -

Bbm:978-3-211-89112-4/1.Pdf

461 BIOGRAFIE 1931 Am 1 Fe ru r In Meran ge oren . 1940 Aussleellung der Familie nach Inns ruck (Op Ion) 19 5 - 9 Besuch der Gewer eschule lnnsbruck, Abteliung Bildhauerei . Duren cas tranzosische Kultunnstllu In Innsbruck nraozosecne Besat uneszon ) Elnblick In die neue Malerel und Plastik Frankreichs (Hans Hartung, Gerard Schneider. Jean Fautner. Wols. Hans Arp Marc I Duchamp. rranncek Kupka. Pablo Picasso, Ma Ernst). Erste unqepenstancliche Zeichnunqen. Llteran che Arb uen. 1948 Erster Ver uch . Te te als Bildwert zu v rwenden 1 49 Beglnn der Inform lien Malerel und Begrundung d r In ormeuen Plastik sowie ntstehunq der ersten Gerumpelplas iken . 1950 Stucium an der Akaderrue d r Bildenden KLlnste Wlen b I Fntz Wo ruba uno an der Staatkchen Akacerrue In S u t rt bel Willi Baumeister Jewell In Stunde. 1953 S ipendiurn fur emen Pans-Auten hal und Stuoienaufen Ilal In Koln . Be e nung mil der Musik von An on Webern. der s n IIsn Muslk. d r surrealis ischen Oichtun unci Kurzfilmen von Giacomo Balla. Die ersten Fo oblid r en s ehen. 1954 - 56 E:nde der inrorrnellen Malerel und Plastik - Beqmn emer konsequen en gegenstandlicllen Figurenmalerel glelchzeltlg rrut den Anfangen der neuen Figuration In der G qenws rtsrnalerei 1 5 Beqrunder oer ..Permanenten veranoerunq In der Kunst" In dies m Zusarnmenh n Ablehnun Jegllcher S il II ung. 1961 Mit lied des Kul urbeuates d s Land s Tirol. Konzepnon und Orqarus tion von Ausstellun en In Inn bruck. Aufbau der .. Modernen Galerie" irn Tiroler Land srnuseurn F rdinand urn. -

Klimt, Kupka, Picasso, and Others – Form Art

KLIMT, KUPKA, PICASSO, AND OTHERS – FORM ART Lower Belvedere 10 March to 19 June 2016 Series C VIII, 1935 1946 Oil on canvas 97 x 105 cm Thyssen-Bornemisza Collections / © Bildrecht, Vienna, 2015 Photo: © Belvedere, Vienna KLIMT, KUPKA, PICASSO, AND OTHERS – FORM ART In the Habsburg Empire during the second half of the nineteenth century, form was more than merely a descriptive concept. It was the expression of a realization, of a particular consciousness. Ultimately, around 1900, form became the basis for a wide variety of non-representational, often ornamental art. The exhibition Klimt, Kupka, Picasso, and Others Form Art, showing at the Lower Belvedere from 10 March to 19 June 2016, explores intellectual constellations and traditions in science, philosophy, and art in the late Habsburg Monarchy, demonstrating a network of connections within an entire cultural region. The show illustrates the continuities and unique characteristics of art in Austria-Hungary. It places a focus on education, demonstrating the great influence this exerts on a cultural region and its enduring contribution to the development of a collective consciousness. Furthermore, it alludes to the fertile ground that from 1900 gave rise to a whole family tree of related art. This will be the first exhibition to explore the common foundations that linked art in the Habsburg Empire and led to the genesis of non-representational art. Klimt, Kupka, Picasso, and Others Form Art embarks on some cultural historical detective work in the former crownlands of the Habsburg Empire and for the first time juxtaposes Czech Cubism with the form art of the Vienna Secession an extremely new -Arco, Director of the Belvedere and 21er H Featuring an unprecedented array of prominent works, the visitor can appreciate this special view of modernism in the Habsburg Empire. -

Silvie Aigner: on the Position of Stone Sculpture in Contemporary Art - the Austrian Context 1

[kunstwerk] krastal Silvie Aigner: On the position of stone sculpture in contemporary art - the Austrian context 1 S i lvie Aigner: On the position of stone sculpture in contemporary art 1 The Austrian context The new departures brought by Modernism created a new direction for historically pedestal-based sculpture, allowing for a transformation of its purposes. From 1960 onwards, the term ”sculpture” was used to summarise diverse positions which also included other media. While sculpture in America acquired new definitions since the 1950’s, the initial development of modernism in Europe started out from the basic form of the figure, holding fast to historical materials such as stone and cast bronze. In spite of this, sculpture in stone emancipated itself from its decorative and representative roles. In Austria, the journey towards contemporary sculpture and object-based artworks only began after 1945. In the 50’s and 60’s, Austrian sculptors such as Fritz Wotruba, Karl Hoflehner, Roland Goeschl and Karl Prantl, Walter Pichler, Cornelius Kolig, Bruno Gironcoli had set internationally recognised benchmarks for the further development of sculpture in Austria. Alongside sculpture, which was tied to its material and to the object, connections with architecture and crossovers with the processes of design or applied art were established. With the developing significance of avant- garde film-making and of ”expanded cinema” in the late Fifties, the field of sculpture was broadened to encompass film, photography and performance art, and particularly so in Austria. These borderlines were fluid, sculptural objects becoming components in process-related works, which were also incorporated into the public domain. -

Press Release

Belvedere 21 Museum of Contemporary Art Arsenalstraße 1 1030 Vienna Opening Hours: Tue to Sun 11 am to 6 pm Late Nights: Thu & Fri 11 am to 6 pm Mon only open on public holidays Press Downloads: belvedere.at/en/press Press Contact: Irene Jäger +43 1 795 57-185 +43 664 800 141 185 [email protected] Belvedere 21, Photo: Lukas Schaller PRESS RELEASE BELVEDERE 21 – MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART The Belvedere 21 is a place of artistic production, reception, and reflection. Open and generously laid out, the building is a key work of Austrian post-war modernity and serves today as a space for discourse and experimentation, where society is explored and discussed. Austrian art of the 20th and 21st centuries and its integration into the international context stands at the centre of the museum’s exhibition activities. A comprehensive educational program, film screenings, lectures, performances, and artist talks seek to encourage a dialogue with the public. Along with its three exhibition floors, the overall concept for the Belvedere 21 also includes the Blickle Kino, a learning centre, and a sculpture garden. Additionally, the building also houses the Artothek des Bundes as well as the archives of the Austrian sculptor Fritz Wotruba. BUILDING HISTORY The Belvedere 21 is located in one of the most significant post-war era buildings. Awarded the Grand Prix d’Architecture, the museum was initially constructed by Viennese architect Karl Schwanzer for the 1958 Brussels World Expo. Its sleek formal structure, glass halls and use of fresh building materials class the pavilion as a prime example of modern architecture. -

The Eastern Question Or Balkan Nationalism(S)

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 Gunnar Hering Lectures Volume 1 Edited by Maria A. Stassinopoulou The volumes of this series are peer-reviewed. Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 Dimitris Stamatopoulos The Eastern Question or Balkan Nationalism(s) Balkan History Reconsidered V&R unipress Vienna University Press Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available online: http://dnb.d-nb.de. ISSN 2625-7092 ISBN 978-3-8471-0830-6 Publications of Vienna University Press are published by V&R unipress GmbH. Sponsored by the Austrian Society of Modern Greek Studies, the Department for Cultural Affairs of the City of Vienna (MA 7), the Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies and the Faculty of Historical and Cultural Studies at the University of Vienna. © 2018, V&R unipress GmbH, Robert-Bosch-Breite 6, 37079 Göttingen, Germany / www.v-r.de This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International license, at DOI 10.14220/9783737008303. For a copy of this license go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Any use in cases other than those permitted by this license requires the prior written permission from the publisher. Cover image: The cover image is based on a photograph of the sculpture by Joannis Avramidis “Mittlere Sechsfigurengruppe”, 1980, Bronze, 110 cm, from the estate of the artist, photograph by Atelier Neumann, Vienna, courtesy of Julia Frank-Avramidis. -

Press Kit WOTRUBA

Vienna, May 5, 2021 Belvedere 21 Arsenalstraße 1 1030 Vienna Opening hours: Tuesday to Sunday 11 am to 6 pm Monday only open on holidays Press downloads: belvedere.at/en/press Press contact: Désirée Schellerer +43 664 800 141 303 [email protected] Church of the Most Holy Trinity on the Georgenberg in Vienna- Mauer, Photo: Johannes Stoll / Belvedere, Vienna WOTRUBA. HEAVENWARDS The Church on the Georgenberg May 6, 2021 to March 13, 2022 An architectural icon created from concrete blocks. Today, The Church of the Most Holy Trinity is considered a modern landmark in Vienna, but in the beginning, the artistic design by sculptor Fritz Wotruba was the subject of much controversy. His design was implemented in collaboration with architect Fritz Gerhard Mayr between 1974 and 1976, resulting in one of Vienna's most striking sacred buildings. Forty-five years after its consecration, the Belvedere is for the first time presenting an exhibition expressly dedicated to the so-called Wotruba Church. "The church is a landmark, and for many, it has achieved cult status. Until now, little has been known about its genesis and place in the post-war era and art historical narrative. The exhibition seeks to fill this gap and provides a fresh perspective on this beloved building," says Stella Rollig, CEO of the Belvedere. The Church of the Most Holy Trinity was consecrated on October 24, 1976, more than a year after Wotruba's death and thirteen years into a challenging evolutionary process. The initial mandate given to the sculptor in 1965 entailed designing a convent with a church for the Carmelite Sisters in Steinbach near Vienna.