SCOPYRIGHT This Copy Has Been Supplied by the Library of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Article

Quarterly Bulletin of The Ornithological Society of New Zealand Volume 7, Number Seven :January l 958 NOTORNIS In continuation of New Zealand Bird Notes BULLETIN OP THE ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ZBALAND (Incorporated) Registered with the G.P.O., Wellington, as a Magazine Edited by R. B. SIBSON, King's College, Auckland S.E.7 Annual Subscription, 10/- (Juniors, 5/-); Endowment Membership, Cl; Life Membership, E10 (for members over thirty years of age). OFFICERS, 1957 - 58 President - MR P. C. BULL, Lower Hutt. North Island Vice-President - MR E. G. TURBOTT, Christchurcb South Island Vice-President - MRS L. E. WALKER, Dunedin Editor- MR R. B. SIBSON, King's College, Auckland S.E.7 Treasurer - MR H. R. McKENZIE, North Road, Clevedon Secretary - MR G. R. WILLIAMS, Wildlife Division, Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington MRS 0. SANSOM, Invercargill; DR R. A. FALLA, Wellington; MR J. C. DAVENPORT, Auckland Contents of Volume 7, Number 7 : January 1958 Some Notes on Muttonbirding in the North Island- W. J. Phillipps 189 Classified Summarised Notes .................................... 191 Annual Locality Reports for Firth of Thames and Manukau Harbour 201 Obituary: W. R. B. Oliver ....................................205 Short Notes mentioning: S.I. Pied Oystercatcher, White-faced Heron, Spotted Shag, Barn Owl, Spur-winged Plover, Crested Grebe, 'Red- legged ' Herons, Myna in !;.I., Bush-hawk, Weka ................ 206 Review8 .................................................... 2 11 Notices. XIIth International Ornithological Congress ............ 212 Nest Records Scherne Publications for sale Donations NOTORNI S VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER SEVEN : JANUARY NINETEEN FIFTY-EIGHT SOME NOTES ON MUTTONBIRDIING IN THE NORTH ISLAND By W. 1. PHILLIPPS During the period 1919- 1924 odd notes were collected on the occurrence of muttonbirds breeding on Mount Pihanga not far from Lake Rotoaira. -

Rowing Australia Annual Report 2011-12

Rowing Australia Annual Report 2011–2012 Rowing Rowing Australia Office Address: 21 Alexandrina Drive, Yarralumla ACT 2600 Postal Address: PO Box 7147, Yarralumla ACT 2600 Phone: (02) 6214 7526 Rowing Australia Fax: (02) 6281 3910 Website: www.rowingaustralia.com.au Annual Report 2011–2012 Winning PartnershiP The Australian Sports Commission proudly supports Rowing Australia The Australian Sports Commission Rowing Australia is one of many is the Australian Government national sporting organisations agency that develops, supports that has formed a winning and invests in sport at all levels in partnership with the Australian Australia. Rowing Australia has Sports Commission to develop its worked closely with the Australian sport in Australia. Sports Commission to develop rowing from community participation to high-level performance. AUSTRALIAN SPORTS COMMISSION www.ausport.gov.au Rowing Australia Annual Report 2011– 2012 In appreciation Rowing Australia would like to thank the following partners and sponsors for the continued support they provide to rowing: Partners Australian Sports Commission Australian Olympic Committee State Associations and affiliated clubs Australian Institute of Sport National Elite Sports Council comprising State Institutes/Academies of Sport Corporate Sponsors 2XU Singapore Airlines Croker Oars Sykes Racing Corporate Supporters & Suppliers Australian Ambulance Service The JRT Partnership contentgroup Designer Paintworks/The Regatta Shop Giant Bikes ICONPHOTO Media Monitors Stage & Screen Travel Services VJ Ryan -

SENATE Official Committee Hansard

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SENATE Official Committee Hansard ECONOMICS LEGISLATION COMMITTEE (Consideration of Estimates) THURSDAY, 20 NOVEMBER 1997 BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE CANBERRA 1997 CONTENTS THURSDAY, 20 NOVEMBER Department of Industry, Science and Tourism— Program 2—Australian Industrial Property Organisation .......... 740 Program 1—Department of Industry, Science and Tourism—Subprogram 1.5—Industry policy ................. 745 Program 9—Australian Customs Service— Subprogram 9.1—Border management ..................... 745 Subprogram 9.2—Commercial services .................... 765 Program 1—Department of Industry, Science and Tourism— Subprogram 1.5—Industry policy ........................ 767 Subprogram 1.1—AusIndustry .......................... 769 Subprogram 1.2—Industry Liaison ....................... 782 Subprogram 1.5—Industry Policy ........................ 788 Subprogram 1.2—Industry liaison ........................ 792 Subprogram 1.4—Sport and Recreation .................... 795 Program 10—Australian Sports Commission .................. 795 Program 11—Australian Sports Drug Agency ................. 795 Department of The Treasury— Program 1—Treasury— Subprogram 1.4—Taxation ............................. 807 Subprogram 1.8—Financial and currency ................... 844 Subprogram 1.8—Finance and currency .................... 847 Program 7—Insurance and Superannuation Commission—Subprogram 7.4—Superannuation ................................. 851 Thursday, 20 November 1997 SENATE—Legislation E 737 -

Shearing Magazine April 2021

. Shearing Promoting our industry, sport and people Number 105: (Vol 37, No 1) April 2021 ISSN 1179-9455 (online) Last Side Publishing Hamilton, New Zealand Megan Whitehead during her nine-hour, lamb shearing world record of 661 at ShearingCroydon Bush 1 on 14 January 2021. Promoting our industry, sport and people Shearing Number 105: (Vol 37, No 1) April 2021 ISSN 1179 - 9455 (online) UNDER COVER STORY CONTENTS Greetings people and welcome to Shearing magazine No. 3 Heiniger advertisement 105. With 60 pages, this is the largest edition in our 37- 4 NZ Woolclassers’ Association news year history. That’s fifty percent bigger than the printed 5 Harry Hughes – ‘Still out there’ editions and best illustrates one obvious advantage of our having gone exclusively ‘digital’. 7 Lister advertisement Our Contents are perhaps dominated by seven tribute 8 Tribute: Des de Belle stories for industry people who have died over the past few 9 Tahi Ngātahi months, notable among them 95-year-old Ian Hutchings, a 10 Training boost/WOMOLife contractor long associated with the Morrinsville and wider Waikato region. It is our privilege to publish their stories 12 Megan Whitehead – full capacity? and to record the exploits and contributions to our industry 14 Tribute: Brian Morrison for which they are best remembered. 16 TJ Law Shearing Supplies Several other stories have historical themes. We are 17 South Canterbury reunion delighted to finally publish a story about Harry Hughes, 18 Wool Medal for Kevin Gellatly who has been on our ‘radar’ for 20 years or more. Also the legendary Bill Vella, a world record holder and contractor 19 Tribute: Veronica ‘Ronnie’ Goss in the 1930s, while we bring to light the shearing exploits 20 Campaign for Wool of a fighter pilot and prisoner-of-war from the WWII era. -

(No. 15)Craccum-1975-049-015.Pdf

Issue 15 If eUc+eJ +• r vtrWMt 1 5 ;vc «. firm « " ^ * ^ 0 Sabs fiafem7 - < ^ U e g «+ i ®'n'S ** ^•Ofi /n«lpr«C+ice ® r h ' » ' r o / t f c S National’s ‘revolutionary’ industrial relations policy Page 2 rfiffldit i --------- U W I l P ions, we are forced to conclude that the osition to the Bill. 10 ED UCATION O F F IC E R - responsible dances etc are a risk to the safety and sec “ It is incredible that any right-thinking for all matters concerning education. Editor - Mike Rann urity of Students Association property people could seriously suggest, as some (your $28.00 worth). If we are to contin MP’s did, that the Bill would lead to the 11 INTERNATIONS AFFAIRS OFFICER ue providing these services either the van breakdown of New Zealand society or to - all matters concerning Internation Technical Editors - Malcolm Walker • dalism must be prevented or the Executive a disasterous fall in the country’s birth Affairs. and Jeremy Templar. will have to close down the facilities at rate,” Mr. Blincoe continued. “ And for night until it stops. MP’s to talk paternalistically of their com 12CULTURAL AFFAIRS OFFICER- Advertising Manager - Paul Gilmour There has been damage to the pool passion for homosexuals yet deny them responsible for the co-ordinations of room also at night and this has forced the legal right to be what they are is sheer the creative activities of all clubs. Reporter - Rob Greenfield the closing of the pool room after 7 p.m. hypocrisy.” Thanks to Raewyn Stone, as was the case in 1974 when damage Mr. -

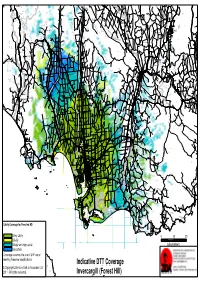

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197

SECTION 6 SCHEDULES Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197 SECTION 6: SCHEDULES SCHEDULE SUBJECT MATTER RELEVANT SECTION PAGE 6.1 Designations and Requirements 3.13 Public Works 199 6.2 Reserves 208 6.3 Rivers and Streams requiring Esplanade Mechanisms 3.7 Financial and Reserve 215 Requirements 6.4 Roading Hierarchy 3.2 Transportation 217 6.5 Design Vehicles 3.2 Transportation 221 6.6 Parking and Access Layouts 3.2 Transportation 213 6.7 Vehicle Parking Requirements 3.2 Transportation 227 6.8 Archaeological Sites 3.4 Heritage 228 6.9 Registered Historic Buildings, Places and Sites 3.4 Heritage 251 6.10 Local Historic Significance (Unregistered) 3.4 Heritage 253 6.11 Sites of Natural or Unique Significance 3.4 Heritage 254 6.12 Significant Tree and Bush Stands 3.4 Heritage 255 6.13 Significant Geological Sites and Landforms 3.4 Heritage 258 6.14 Significant Wetland and Wildlife Habitats 3.4 Heritage 274 6.15 Amalgamated with Schedule 6.14 277 6.16 Information Requirements for Resource Consent 2.2 The Planning Process 278 Applications 6.17 Guidelines for Signs 4.5 Urban Resource Area 281 6.18 Airport Approach Vectors 3.2 Transportation 283 6.19 Waterbody Speed Limits and Reserved Areas 3.5 Water 284 6.20 Reserve Development Programme 3.7 Financial and Reserve 286 Requirements 6.21 Railway Sight Lines 3.2 Transportation 287 6.22 Edendale Dairy Plant Development Concept Plan 288 6.23 Stewart Island Industrial Area Concept Plan 293 6.24 Wilding Trees Maps 295 6.25 Te Anau Residential Zone B 298 6.26 Eweburn Resource Area 301 Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 198 6.1 DESIGNATIONS AND REQUIREMENTS This Schedule cross references with Section 3.13 at Page 124 Desig. -

Beneath the Reflections

Beneath the Reflections A user’s guide to the Fiordland (Te Moana o Atawhenua) Marine Area Acknowledgements This guide was prepared by the Fiordland Marine Guardians, the Ministry for the Environment, the Ministry for Primary Industries (formerly the Ministry of Fisheries and MAF Biosecurity New Zealand), the Department of Conservation, and Environment Southland. This guide would not have been possible without the assistance of a great many people who provided information, advice and photos. To each and everyone one of you we offer our sincere gratitude. We formally acknowledge Fiordland Cinema for the scenes from the film Ata Whenua and Land Information New Zealand for supplying navigational charts for generating anchorage maps. Cover photo kindly provided by Destination Fiordland. Credit: J. Vale Disclaimer While reasonable endeavours have been made to ensure this information is accurate and up to date, the New Zealand Government makes no warranty, express or implied, nor assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, correctness, completeness or use of any information that is available or referred to in this publication. The contents of this guide should not be construed as authoritative in any way and may be subject to change without notice. Those using the guide should seek specific and up to date information from an authoritative source in relation to: fishing, navigation, moorings, anchorages and radio communications in and around the fiords. Each page in this guide must be read in conjunction with this disclaimer and any other disclaimer that forms part of it. Those who ignore this disclaimer do so at their own risk. -

The New Zealand Gazette 1489

5 ,SEPTEMBER THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 1489 Allenton- Onetangi, Community Hall. Creek Road Hall. Ostend, First Aid Room. School. Palm Beach, Domain Hall. Anama School. Rocky Bay, Omiha Hall. Arundel School. Surfdale, Surfdale Hall. Ashburton- Borough Chambers. College, Junior Division, Cameron Street. College, Senior DiviSIon, Cass Street. Courthouse. Hampstead School, Wellington Street. Burkes Pass Public Hall. Avon Electoral District Carew School. Aranui- Cave Public Hall. Public School, Breezes Road. Chamberlain (Albury), Coal Mine Road Comer, Mr M. A. St. James School, Rowan Avenue. Fraser's House. Bromley Public School. Clandeboye School. Burwood- Coldstream, Mr Studholmes Whare. Brethren Sunday School, Bassett Street. Cricklewood Public Hall. Cresswell Motors Garage, New Brighton Road. Ealing Public Hall. Public School, New Brighton Road. Eiffelton SchooL Dallington Anglican Sunday School, Gayhurst Road. Fairlie Courthouse. Linwood North Public School, Woodham Road. Flemington SchooL New Brighton- Gapes Valley Public Hall. Central School, Seaview Road. Geraldine- Freeville Public School, Sandy Avenue. Borough Chambers. Garage, corner Union and Rodney Streets. Variety Trading Co., Talbot Street. North Beach Methodist Church Hall, Marriotts Road. Greenstreet Hall. North New Brighton- Hermitage, Mount Cook, Wakefield Cottage. Peace Memorial Hall, Marine Parade. Hilton SchooL Public School, Leaver Terrace. Hinds SchooL Sandilands Garage, 9 Coulter Street. Kakahu Bush Public Hall. Shirley- Kimbell Old School Building. Garage, 40 Vardon Crescent. Lake Pukaki SchooL Public School, Banks Avenue. Lismore SchooL Rowe Memorial Hall, North Parade. Lowc1iffe SchooL South New Brighton- Maronan Road Hall. Garage, 1 Caspian Street. Mayfield School. Public School, Estuary Road. Milford School. Wainoni- Montalto SchooL Avondale Primary School, Breezes Road. Mount Nessing (Albury) Public Hall. -

Rowing Australia Annual Report 2015 Contents Rowing Australia Limited 2015 Office Bearers

In appreciation Rowing Australia would like to thank the following partners and sponsors for the continued support they provide to rowing: Partners Australian Sports Commission Australian Institute of Sport Australian Olympic Committee Australian Paralympic Committee State Associations and affiliated clubs National Institute Network comprising State Institutes/Academies of Sport Destination New South Wales World Rowing (FISA) Major Sponsors Hancock Prospecting Georgina Hope Foundation Sponsors Croker Oars Sykes Racing JL Racing Filippi Corporate Supporters & Suppliers Australian Ambulance Service The JRT Partnership Designer Paintworks/The Regatta Shop ICONPHOTO Media Monitors Andrew Jones Travel VJ Ryan & Co iSENTIA Sports Link International Sportlyzer Key Foundations National Bromley Trust Olympic Boat Fleet Trust Bobby Pearce Foundation Photo Acknowledgements Getty Images Delly Carr ,FRQSKRWR 2 Rowing Australia Annual Report 2015 Contents Rowing Australia Limited 2015 Office Bearers Rowing Australia Limited 2015 Office Bearers 4 Board of Rowing Australia Company Directors and Chief Executive Officer 6 Rob Scott President (appointed 1 October, 2014) John Boultbee Director (appointed 29 June 2007, resigned 24 May 2015) President’s Report 9 Sally Capp Director (appointed 20 May, 2013) Message from the Australian Sports Commission 13 Andrew Guerin Director (appointed 30 November, 2013) Chief Executive Officer’s Report 14 Flavia Gobbo Director (appointed 19 December, 2012) Merrick Howes Director (appointed 29 May, 2014) Competition Report -

The Archaeology of Otago

The archaeology of Otago Jill Hamel Published by Department of Conservation PO Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand Cover: Stone ruins of cottages at the ill-fated Pactolus Claim in the upper Nevis The pond in the foreground was probably made by a hydraulic elevator This report was prepared for publication by DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit; editing by Jaap Jasperse and Ian Mackenzie, design and layout by Ian Mackenzie, maps by Chris Edkins Publication was approved by the Manager, Science & Research Unit, Science Technology and Information Services, Department of Conservation, Wellington © Copyright May 2001, Department of Conservation ISBN 0478220162 Cataloguing in Publication Hamel, Jill, 1932- The archaeology of Otago / Jill Hamel Wellington, NZ : Dept of Conservation, 2001 xii, 222 p ; 30 cm Includes bibliographical references ISBN 0478220162 1 ArchaeologyNew ZealandOtago Region I Title ii Contents Foreword vii Preface ix Abstract 1 PART 1 THE PREHISTORIC PERIOD 1 In the beginning 4 11 Climate, deforestation, and fire 4 12 The date of the first human settlements 9 2 Natural resources 14 21 Moa hunting 14 The birds themselves 14 The camps and villages of those who hunted moa 15 22 Birds other than moa 20 23 Marine mammals 29 24 Fishing 32 25 Shellfish gathering and seasonality 35 26 Introduced animalskuri and kiore 39 27 Plant foods and ovens 42 28 Stone resources 48 Silcrete and porcellanite 48 Nephrite 51 Other rock types 53 The patterns of rock types in sites 54 29 Rock shelters and rock art 58 3 Settlements 62 31 Defended -

The Effects of Proportional Representation on Election

THE EFFECTS OF PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION ON ELECTION LAWMAKING IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND by Joshua Ferrer A Thesis Submitted to the Politics Programme University of Otago in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts January 2020 ii iii ABSTRACT It is widely recognized that most politicians are self-interested and desire election rules beneficial to their reelection. Although partisanship in electoral system reform is well- understood, the factors that encourage or constrain partisan manipulation of the other democratic “rules of the game”—including election administration, franchise laws, campaign finance, boundary drawing, and electoral governance—has received little scholarly attention to date. Aotearoa New Zealand remains the only established democracy to switch from a non-proportional to a proportional electoral system and thus presents a natural experiment to test the effects of electoral system change on the politics of election lawmaking. Using a longitudinal comparative case study analysis, this thesis examines partisan and demobilizing election reforms passed between 1970 and 1993 under first-past- the-post and between 1997 and 2018 under mixed-member proportional representation (MMP). Although partisan election reforms have not diminished under MMP, demobilizing reforms have become less common. Regression analysis uncovers evidence that partisan election lawmaking is more likely when the effective number of parties in parliament is lower, when non-voters have more leverage, and when reforms are pursued that diminish electoral participation. iv To Arthur Klatsky, with all my love v PREFACE This thesis would not be what it is without the generosity, time, and aroha of countless people. For the sake of the Otago Politics Department’s printing budget, I will attempt to be brief.