Change Management for Organizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stenographer (Post Code-01)

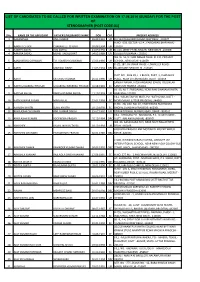

LIST OF CANDIDATES TO BE CALLED FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION ON 17.08.2014 (SUNDAY) FOR THE POST OF STENOGRAPHER (POST CODE-01) SNo. NAME OF THE APPLICANT FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME DOB CAT. PRESENT ADDRESS 1 AAKANKSHA ANIL KUMAR 28.09.1991 UR B II 544 RAGHUBIR NAGAR NEW DELHI -110027 H.NO. -539, SECTOR -15-A , FARIDABAD (HARYANA) - 2 AAKRITI CHUGH CHARANJEET CHUGH 30.08.1994 UR 121007 3 AAKRITI GOYAL AJAI GOYAL 21.09.1992 UR B -116, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110008 4 AAMIRA SADIQ MOHD. SADIQ BHAT 04.05.1989 UR GOOSU PULWAMA - 192301 WZ /G -56, UTTAM NAGAR NEAR, M.C.D. PRIMARY 5 AANOUKSHA GOSWAMI T.R. SOMESH GOSWAMI 15.03.1995 UR SCHOOL, NEW DELHI -110059 R -ZE, 187, JAI VIHAR PHASE -I, NANGLOI ROAD, 6 AARTI MAHIPAL SINGH 21.03.1994 OBC NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI -110043 PLOT NO. -28 & 29, J -1 BLOCK, PART -1, CHANAKYA 7 AARTI SATENDER KUMAR 20.01.1990 UR PLACE, NEAR UTTAM NAGAR, DELHI -110059 SANJAY NAGAR, HOSHANGABAD (GWOL TOLI) NEAR 8 AARTI GULABRAO THOSAR GULABRAO BAKERAO THOSAR 30.08.1991 SC SANTOSHI TEMPLE -461001 I B -35, N.I.T. FARIDABAD, NEAR RAM DHARAM KANTA, 9 AASTHA AHUJA RAKESH KUMAR AHUJA 11.10.1993 UR HARYANA -121001 VILL. -MILAK TAJPUR MAFI, PO. -KATHGHAR, DISTT. - 10 AATIK KUMAR SAGAR MADAN LAL 22.01.1993 SC MORADABAD (UTTAR PRADESH) -244001 H.NO. -78, GALI NO. 02, KHATIKPURA BUDHWARA 11 AAYUSHI KHATRI SUNIL KHATRI 10.10.1993 SC BHOPAL (MADHYA PRADESH) -462001 12 ABHILASHA CHOUHAN ANIL KUMAR SINGH 25.07.1992 UR RIYASAT PAWAI, AURANGABAD, BIHAR - 824101 VILL. -

CHAPTER VI (Contd.) Section-II Review of Economic Activities and Financial Position of the State

( 283) CHAPTER VI (Contd.) Section-II Review of Economic Activities and Financial Position of the State The economy of the Princely State of Gooch Behar, some scholars held, was of a static semi-feudal nature, heavily dependent upon traditional agriculture in pre-British days. The minimum daily needs of the people could be met with the meagre resource available to them within the State.' But there was merely subsistence living and no economic prosperity and social mobility in the State. There was a lack of transport and communication and no foreign contact. Hence no trade and commerce could develop either within the State or with the outside world.' With the conclusion of a treaty between the Coach Behar State and the English East India Company in 1773 (which was in the latter's favour), this intercourse began to generate its impact on the traditional economic set up of this region and the consequent change followed the logic of history. The reign of Harendra Narayan (1783 -1839) had set the stage for change. The State of Coach Behar came into direct contact with the British administration. From then onwards the land tenure system and land revenue settlement began to be geared into motion and the traditional agrarian economy of the state started shaking off its age old slumber.3 Before the arrival of the English East India Company and at the initial period of their rule the economy of Bengal was mainly dependent on agriculture and artisan industry.' But British policy brought about a commercial revolution, estalished a new economy and bound India's economy to the heels of the British economy, the process of deindustrialisation commenced' and gradually India was converted into a centre for the supply of raw-materials for British industries and a market for the import of British manufactured articles. -

Lions Clubs International

GN1067D Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Only - (President, Secretary or Treasure) District 322C2 District Club Club Name Title (Missing) District 322C2 26074 BERHAMPUR GJM President District 322C2 26074 BERHAMPUR GJM Secretary District 322C2 26074 BERHAMPUR GJM Treasurer District 322C2 30428 BALASORE President District 322C2 30428 BALASORE Secretary District 322C2 30428 BALASORE Treasurer District 322C2 32568 RAYAGADA President District 322C2 32568 RAYAGADA Secretary District 322C2 32568 RAYAGADA Treasurer District 322C2 37621 TITILAGARH President District 322C2 37621 TITILAGARH Secretary District 322C2 37621 TITILAGARH Treasurer District 322C2 38219 GANJAM President District 322C2 38219 GANJAM Secretary District 322C2 38219 GANJAM Treasurer District 322C2 38735 PATNAGARH President District 322C2 38735 PATNAGARH Secretary District 322C2 38735 PATNAGARH Treasurer District 322C2 38834 KANTABANJI President District 322C2 38834 KANTABANJI Secretary District 322C2 38834 KANTABANJI Treasurer District 322C2 39318 BARIPADA President District 322C2 39318 BARIPADA Secretary District 322C2 39318 BARIPADA Treasurer District 322C2 40058 DHENKANAL President District 322C2 40058 DHENKANAL Secretary District 322C2 40058 DHENKANAL Treasurer District 322C2 45961 NOWRANGPUR President District 322C2 45961 NOWRANGPUR Secretary District 322C2 45961 NOWRANGPUR Treasurer District 322C2 45963 SURADA President District 322C2 45963 SURADA Secretary District 322C2 45963 SURADA Treasurer District 322C2 50300 KALUNGA President Run 7/2/2007 -

View Entire Book

Orissa Review * April-May - 2009 Integration of Princely States Under Dr. Harekrushna Mahtab Balabhadra Ghadai The Constitution of Orissa Order-1936 got the different parts of the Princely States in Orissa. In approval of the British king on 3rd March, 1936. 1938 Praja Mandals (People's Association) were It was announced that the new province would formed and under their banner, struggle began come into being on 1st April, 1936 with Sir John for securing democratic rights. In the Princely State Austin Hubback, I.C.S. as the Governor. On the of Talcher a movement against feudal exploitation appointed day in a solemn ceremony held at the made significant advance. There was unrest at Ravenshaw College Hall, Cuttack, Sir John Austin Dhenkanal also where the Ruler tried his best to Hubback was administered the oath of office by suppress it. In October 1938, six persons including Sir Courtney Terrel, the Chief Justice of Bihar a 12 year old boy named Baji Rout died as a and Orissa High Court. The Governor read out result of firing. In Ranpur there was an out-break the message of goodwill received from the king- of lawlessness and the situation became serious emperor George VI and the Viceroy of India in January 1939 when the Political Agent Major Lord Linlithgow, for the people of Orissa. Thus, R.L. Bazelgatte was messacred by the mob on 5 the long cherished dream of the Oriya speaking January, 1939 at Ranpur. The troops were sent people of years at last became a reality. to crush the people's movement. -

L&T Sambalpur-Rourkela Tollway Limited

July 24, 2020 Revised L&T Sambalpur-Rourkela Tollway Limited: Rating upgraded Summary of rating action Previous Rated Amount Current Rated Amount Instrument* Rating Action (Rs. crore) (Rs. crore) [ICRA]A-(Stable); upgraded Fund based - Term Loans 990.98 964.88 from [ICRA]BBB+(Stable) Total 990.98 964.88 *Instrument details are provided in Annexure-1 Rationale The upgrade of the rating assigned to L&T Sambalpur-Rourkela Tollway Limited (L&T SRTL) takes into account the healthy improvement in toll collections since the commencement of tolling in March 2018 along with regular receipt of operational grant from the Odisha Works Department, Government of Odisha (GoO), and reduction in interest rate which coupled with improved toll collections has resulted in an improvement in its debt coverage indicators. The rating continues to draw comfort from the operational stage of the project, and the attractive location of the project stretch between Sambalpur and Rourkela (two prominent cities in Odisha) connecting various mineral-rich areas in the region with no major alternate route risk, and strong financial flexibility arising from the long tail period (balance concession period post debt repayment) which can be used to refinance the existing debt with longer tenure as well as by virtue of having a strong and experienced parent—L&T Infrastructure Development Project Limited (L&T IDPL, rated [ICRA]AA(Stable)/[ICRA]A1+)—thus imparting financial flexibility to L&T SRTL. ICRA also draws comfort from the presence of structural features such as escrow mechanism, debt service reserve (DSR) in the form of bank guarantee equivalent to around one quarter’s debt servicing obligations, and reserves to be built for major maintenance and bullet payment at the end of the loan tenure. -

Official Website of Bargarh

Official Website of Bargarh District http://bargarh.nic.in/freedomfighters.htm Home | History | Culture | Tourism | Geography | Personalities | Photo Album | Sitemap | Feedback 1:52:28 PM FREEDOM FIGHTERS District at a Glance Right to Information FREEDOM FIGHTERS 1857 Saheed Madho Singh of Ghess in Bargarh district is one of those martyrs DM/Collector who have fought against the British during the first War of Indian Independence, Govt. Departments 1857 to drive them out from the Indian soil. He was hanged un to death on 31 st Census December 1858. The Government of Orissa in I & P R Department are celebrating Telephone Directory this day as Veerata Divas at State level. Madho Singh was joined in this struggle by Red Cross (IRCS) his four sons named Hate Singh, Kunjal Singh, Bairi Singh and Airi Singh who had also to sacrifice their lives for the same cause. His son-in-law named Narayan Singh People Representatives also had to meet the same fate for the same cause. It is a rare example in the DRDA Activities history of the Freedom Struggle of the country when an entire family of the father, ZP / Panchayat Samiti all the four sons and the only son-in-law has sacrificed their lives for the cause of DISC the freedom of the motherland. However, the history of Indian Freedom Struggle has failed to record the heroic deeds of and the great sacrifice made by these OMGI martyrs. MPLAD/MLALAD When Veer Surendra Sai arrived at Sambalpur in October 1857, consequent NREGA on the breaking open of the Hajaribagh Jail by the revolutionaries, he was joined by ROR View (e-Bhulekh) Madho Singh and others in this great struggle. -

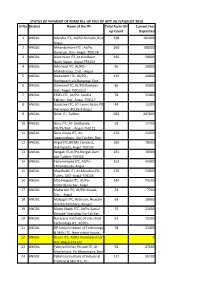

ANGUL Adarsha ITC, At/PO-Rantalei,Dist- 338 101400 Angul 2 ANGUL Akhandalmani ITC , At/Po

STATUS OF PAYMENT OF FORM FILL-UP FEES OF AITT JULY/AUGUST 2018 Sl No District Name of the ITI Total Form fill- Current fees up Count Deposited 1 ANGUL Adarsha ITC, At/PO-Rantalei,Dist- 338 101400 Angul 2 ANGUL Akhandalmani ITC , At/Po. 360 108000 Banarpal, Dist- Angul- 759128 3 ANGUL Aluminium ITC,At-Kandasar, 196 58800 Nalco Nagar, Angul-759122 4 ANGUL Ashirwad ITC, At/PO - 96 28800 Mahidharpur, Dist.- Angul 5 ANGUL Biswanath ITC, At/PO - 136 40800 Budhapank,via-Banarpal, Dist.- 6 ANGUL Diamond ITC, At/PO-Rantalei, 86 25800 Dist- Angul-759122,0 7 ANGUL ESSEL ITC, At/PO- Kaniha 78 23400 Talcher, Dist.-Angul-759117 8 ANGUL Gayatree ITC, AT-Laxmi Bazar,PO- 44 13200 Vikrampur,FCI,Dist-Angul 9 ANGUL Govt. ITI, Talcher 692 207600 10 ANGUL Guru ITC, At- Similipada, 59 17700 PO/PS/Dist. - Angul-759122 11 ANGUL Guru Krupa ITC, At- 170 51000 Jagannathpur, Via-Talcher, Dist- 12 ANGUL Angul ITC,(RCMS Campus), 260 78000 Hakimpada, Angul-759143 13 ANGUL Rengali ITI,At/Po-Rengali Dam 261 78300 site,Talcher-759105 14 ANGUL Kaminimayee ITC, At/Po- 153 45900 Chhendipada, Angul 15 ANGUL Maa Budhi ITI, At-Maratira,PO- 176 52800 Tubey, DIST-Angul-759145 16 ANGUL Maa Hingula ITC, At/Po- 244 73200 talabrda,talcher, Angul 17 ANGUL Maharishi ITC, At/PO-Kosala, 24 7200 Dist. - Angul 18 ANGUL Malyagiri ITC, Batisuan, Nuasahi 63 18900 Dimiria Pallahara, Anugul 19 ANGUL Matru Shakti ITC, At/Po-Samal 72 21600 Barrage Township,Via-Talcher, 20 ANGUL Narayana Institute of Industrial 51 15300 Technology ITC, At/PO- 21 ANGUL OP Jindal Institute of Technology 78 23400 & Skills ITC, Near cricuit house, 22 ANGUL Orissa ITC, At/Po-Panchamahala 0 Dist-Angul-759122 23 ANGUL Pabitra Mohan Private ITI, At- 92 27600 Manikmara, Po-Dharampur, Dist- 24 ANGUL Pallahara Institute of Industrial 117 35100 Training & Skill ITC, At - 25 ANGUL Pathanisamanta ITC,S-2/5 191 57300 Industrial Estate, Hakimpada, 26 ANGUL Satyanarayan ITC, At-Boinda, PO- 0 Kishoreganj, Dist-Angul – 27 ANGUL Shreedhriti ITC, Jagannath 114 34200 Nagar, Po-Banarpal, Dist-Angul- 28 ANGUL Shivashakti ITC, At -Bikashnagar, 0 Tarang, Dist. -

Review Article

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 9, Issue, 06, pp.52316-52318, June, 2017 ISSN: 0975-833X REVIEW ARTICLE TRANSPORT SYSTEM AND MODES OF CONVEYANCE IN COASTAL ODISHA: A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW *Dr. Gokulananda Patro Lecturer in History, K.M.Science College, Narendrapur, Ganjam (Odisha) India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: System of Transport and conveyance constitutes an amazing chapter in the economic history of Received 09th March, 2017 Odisha. No study on the economic history of Odisha can be completed without the reference of the Received in revised form means of transport and conveyance. Hence, an attempt has been made in this paper to discuss various 18th April, 2017 means of transport and conveyance in medieval Odisha. th Accepted 29 May, 2017 th Published online 20 June, 2017 Key words: Transport and conveyance constitutes. Copyright©2017, Dr. Gokulananda Patro. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Citation: Dr. Gokulananda Patro, 2017. “Transport system and modes of conveyance in coastal Odisha: A historical overview”, International Journal of Current Research, 9, (06), 52316-52318. INTRODUCTION flat-bottomed and able to carry about 25 tons of burdens. The palanquin being carried by four to six persons were used for Coastal Odisha comprised the four undivided districts i.e. conveyance. The lorries, trucks and buses were introduced in Balasore, Cuttack, Puri and Ganjam lying on the shore of the Orissa for transportation after the 30’s of the 20th century, but Bay of Bengal. -

List of Colleges Affiliated to Sambalpur University

List of Colleges affiliated to Sambalpur University Sl. No. Name, address & Contact Year Status Gen / Present 2f or Exam Stream with Sanctioned strength No. of the college of Govt/ Profes Status of 12b Code (subject to change: to be verified from the Estt. Pvt. ? sional Affilia- college office/website) Aided P G ! tion Non- WC ! (P/T) aided Arts Sc. Com. Others (Prof) Total 1. +3 Degree College, 1996 Pvt. Gen Perma - - 139 96 - - - 96 Karlapada, Kalahandi, (96- Non- nent 9937526567, 9777224521 97) aided (P) 2. +3 Women’s College, 1995 Pvt. Gen P - 130 128 - 64 - 192 Kantabanji, Bolangir, Non- W 9437243067, 9556159589 aided 3. +3 Degree College, 1990 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 055 128 - - - 128 Sinapali, Nuapada aided (03-04) 9778697083,6671-235601 4. +3 Degree College, Tora, 1995 Pvt. Gen P-2005 - 159 128 - - - 128 Dist. Bargarh, Non- 9238773781, 9178005393 Aided 5. Area Education Society 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2002 12b 066 64 - - - 64 (AES) College, Tarbha, Aided Subarnapur, 06654- 296902, 9437020830 6. Asian Workers’ 1984 Pvt. Prof P 12b - - - 64 PGDIRPM 136 Development Institute, Aided 48 B.Lib.Sc. Rourkela, Sundargarh 24 DEEM 06612640116, 9238345527 www.awdibmt.net , [email protected] 7. Agalpur Panchayat Samiti 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 003 128 64 - - 192 College, Roth, Bolangir Aided 06653-278241,9938322893 www.apscollege.net 8. Agalpur Science College, 2001 Pvt. Tempo - - 160 64 - - - 64 Agalpur, Bolangir Aided rary (T) 9437759791, 9. Anchal College, 1965 Pvt. Gen P 12 b 001 192 128 24 - 344 Padampur, Bargarh Aided 6683-223424, 0437403294 10. Anchalik Kishan College, 1983 Pvt. -

GIPE-017791-Contents.Pdf (2.126Mb)

OFFICIAL AG~NTS . FOR THE SALE OF GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. In India. MESSRS. THA.CXBK, SPINK & Co., Calcutta and Simla. · MESSRS. NEWKA.N & Co., Calcutta. MESSRS. HIGGINBOTHA.M & Co., Madras. MESSRS. THA.Ci:BB & Co., Ln., Bombay. MESSRS . .A.. J. CoHBRIDGB & Co., Bombay. THE SUPERINTENDENT, .A.M:ERICA.N BA.l'TIS'l MISSION PRESS, Ran~toon. Mas. R.l.DHA.BA.I ATKARA.M SA.aooN, Bombay. llissas. R. CA.HBRA.Y & Co., Calcutta. Ru SA.HIB M. GuL&B SINGH & SoNs, Proprietors of the Mufid.i-am Press, Lahore, Punjab. MEsSRS. THoMPSON & Co., Madras. MESSRS. S. MuRTHY & Co., Madras. MESSRS. GoPA.L NA.RA.YEN & Co., Bombay. AhssRs. B. BuiERlEB & Co., 25 Cornwallis Street,· Calcutta. MBssas. S. K. LA.HlRI & Co., Printers and Booksellers, College Street, Calcutta. MESSRS. V. KA.LYA.NA.RUIA. IYER & Co., Booksellers, &c., Madras. MESSRS. D. B. TA.RA.POREVA.LA., SoNs & Co., Booksellers, Bombay. MESSRS. G. A; NA.TESON & Co., Madras. MR. N. B. MA.THUR, Superintendent, Nazair Kanum Hind Press, AJlahabad. - TnB CA.LCUTTA. ScHOOL Boox SociETY. MR. SUNDER PA.NDURA.NG, Bombay. MESSRs. A.M. A.ND J. FERGusoN, Ceylon. MEssRsrTEMPI.B & Co., Madras. · MEssRs. CoHBRIDGB & Co., Madras •. MESSRS. A. R. PILLA.I & Co., Trivandrum. ~bssRs. A. CHA.ND &-Co., Lahore, Punjab. ·- .·· BA.Bu S. C. T.A.LUXDA.B, Proprietor, Students & Co., Ooocli Behar. ------' In $ng~a»a.~ AIR. E. A. • .ARNOLD, 41 & 43 -M.ddo:x:• Street, Bond Street, London, W. , .. MESSRS. CoNSTA.BLB & Co., 10 Orange· Sheet, Leicester Square, London, W. C. , MEssRs. GaiNDLA.Y & Co., 64. Parliament Street, London, S. -

Tahasildar, Talcher

IN RESPECT OF BANABASPUR SAND BED FOR WINING OF RIVER SAND OVER AN AREA OF 17.18 ACRES OR 6.872 HECTARES IN VILLAGE- BANABASPUR, TAHASIL-TALCHER OF ANGUL DISTRICT, ODISHA PREPARED FOR & ON BEHALF OF TAHASILDAR, TALCHER DISTRICT-ANGUL, ODISHA APPENDIX 1 FORM – I (I) Basic Information SL.NO. ITEM DETAILS 1 Name of the Project/s Banabaspur sand Quarry (Singharha jor River) 2 SL. No. in the Schedule Project Activity 1(a) (i) Mining of Minerals. Propose Capacity/ area/ length/ Proposed Production Capacity – tonnage to be handled/command About 12500 Cum of Sand will be 3 area/ lease area/number or wells produced during the Plan Period to be drilled Total Lease Area- 17.18 Acres or 6.872 Ha 4 New/Expansion/Modernization New 5 Existing Capacity/Area etc. Not Applicable, since it is a new project. Category of Project i.e. 'A' or 'B' It is a category ‘B’ project. (<25 Ha all the minor mineral mining lease areas are considered as B2, as per 6 MoEF, GoI, Office Memorandum No. J-13012/12/2013-IA-II ( I), d a t e d : 24-12-2013). non coal mine lease) Does it attract the general 7 No Condition? If yes, please specify. 8 Does it attract the specific Condition? If yes, please specify No The applied area over 6.872 hectares is located in village- Banabaspur and is bounded by 20°59I15.3II N to Location 20°59I40.7II N and 85°02I22.0II E to 85°02I49.8II E. 9 Plot No.- 61, Khata No.- 106 Plot/Survey/Khasra No. -

Mental Health Care and Human Rights

Mental Health Care and Human Rights Editors D Nagaraja Pratima Murthy National Human Rights Commission New Delhi National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences Bangalore Title: Mental Health Care and Human Rights D Nagaraja Pratima Murthy Technical and Editorial Assistance Y S R Murthy, Director (Research), NHRC Utpal Narayan Sarkar, AIO, NHRC Joint copyright: National Human Rights Commission, New Delhi and National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Bangalore. First Edition: 2008 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holders ISBN- 978-81-9044117-5 Published by: National Human Rights Commission Faridkot House, Copernicus Marg New Delhi 110 001, India Tel: 23385368 Fax: 23384863 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.nhrc.nic.in Design and printed by Rajika Press Services Pvt. Ltd. Cover: Biplab Kundu Table of Contents Editors and Contributors............................................................... 5 Foreword........................................................................................ 7 Preface............................................................................................ 9 Editors’ Introduction.................................................................... 11 Section 1 Human rights in mental health care: ........................................... 15 an introduction Lakshmidhar