The Writings in Prose and Verse of Rudyard Kipling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pennsylvania Lion Or Panther

T he A l to o n a T ri b u n e Pu bl i shi n g Co . A LTO O N A , P E N N A . l 9 l 7 C O PY R I G H T E D A L L R I G H T S R E S E RV E D H O N . C L E MA N . S O B E R O K , F o r 2 1 ea r n n i i o Y s a M e m b e r of th e P e n sy l va a G a m e C o m m i ss n . — o r R e n o n e h o t I n ti m t F ri n a ro H l W ld w d S a e e d of A n a l . Pre face H istory Description Habits Early Prevalence The Great S laughter The Biggest Panther Diminish ing Numbers The Last Phase 44 - 48 - — R e Introduction " Sporting. Possibilities 49 52 Superstitions 53—57 Tentative List o f Panthers Killed in Pennsylvania S ince 1 860 I I I f X . Ode to a Stu fed Panther I . PREFACE . H E obj ect o f this pamphlet is to produce a narra tive blending the history and romance of the once plenti ful Lion of Pennsylvania . While pages have been written in natural histories describing ’ this animal s unpleasant characteristics , not a word has been said in its favor . -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

Downbeat.Com March 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. DOWNBEAT.COM MARCH 2014 D O W N B E AT DIANNE REEVES /// LOU DONALDSON /// GEORGE COLLIGAN /// CRAIG HANDY /// JAZZ CAMP GUIDE MARCH 2014 March 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 3 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Kathleen Costanza Design Intern LoriAnne Nelson ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene -

Radio 4 Listings for 29 February – 6 March 2020 Page 1 of 14

Radio 4 Listings for 29 February – 6 March 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 29 FEBRUARY 2020 Series 41 SAT 10:30 The Patch (m000fwj9) Torry, Aberdeen SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000fq5n) The Wilberforce Way with Inderjit Bhogal National and international news from BBC Radio 4 The random postcode takes us to an extraordinary pet shop Clare Balding walks with Sikh-turned-Methodist, Inderjit where something terrible has been happening to customers. Bhogal, along part of the Wilberforce Way in East Yorkshire. SAT 00:30 The Crying Book, by Heather Christle Inderjit created this long distance walking route to honour Torry is a deprived area of Aberdeen, known for addiction (m000fq5q) Wilberforce who led the campaign against the slave trade. They issues. It's also full of dog owners. In the local pet shop we Episode 5 start at Pocklington School, where Wilberforce studied, and discover Anna who says that a number of her customers have ramble canal-side to Melbourne Ings. Inderjit Bhogal has an died recently from a fake prescription drug. We wait for her Shedding tears is a universal human experience, but why and extraordinary personal story: Born in Kenya he and his family most regular customer, Stuart, to help us get to the bottom of it how do we cry? fled, via Tanzania, to Dudley in the West Midlands in the early - but where is he? 1960s. He couldn’t find anywhere to practice his Sikh faith so American poet Heather Christle has lost a dear friend to suicide started attending his local Methodist chapel where he became Producer/presenter: Polly Weston and must now reckon with her own depression. -

IMPOSSIBLE LANDSCAPES (First Edit)

Delta Green Impossible Landscapes ©2020 The Delta Green Partnership IMPOSSIBLE LANDSCAPES A CAMPAIGN OF WONDER, HORROR, AND CONSPIRACY, FOR DELTA GREEN: THE ROLE-PLAYING GAME BY DENNIS DETWILLER ARC DREAM PUBLISHING PRESENTS DELTA GREEN: IMPOSSIBLE LANDSCAPES BY DENNIS DETWILLER DEVELOPERS & EDITORS DENNIS DETWILLER & SHANE IVEY ART DIRECTOR & ILLUSTRATOR DENNIS DETWILLER GRAPHIC DESIGNER SIMEON COGSWELL COPY EDITOR LISA PADOL DELTA GREEN CREATED BY DENNIS DETWILLER, ADAM SCOTT GLANCY & JOHN SCOTT TYNES All writing and art ©2019 Dennis Detwiller. “Is the darkness/Ours to take?/Bathed in lightness/Bathed in heat/All is well/As long as we keep spinning/Here and now/Dancing behind a wall/Hear the old songs/And laughter within/All forgiven/Always and never been true.” 1 Delta Green Impossible Landscapes ©2020 The Delta Green Partnership IMPOSSIBLE LANDSCAPES 1 THIS BOOK HAS TEETH… 19 INTRODUCTION 20 CAMPAIGN STRUCTURE 20 IN THE FIELD: TRANSIT BETWEEN OPERATIONS 20 OPERATIONAL SUMMARIES AND STRUCTURE 21 The Night Floors 21 A Volume of Secret Faces 21 Like a Map Made of Skin 21 The End of the World of the End 22 DISINFORMATION: MENTAL ILLNESS AND THE KING IN YELLOW 22 PART ONE: THE KING IN YELLOW 23 DISINFORMATION: CARCOSA, THE KING IN YELLOW, AND HASTUR 23 THE BOOK, THE NIGHT WORLD, AND CARCOSA 24 IN THE FIELD: THEMES OF THE KING IN YELLOW 24 DELTA GREEN AND THE KING IN YELLOW 25 THE FIRST KNOWN OUTBREAK OF LE ROI EN JAUNE (1895) 26 DISINFORMATION: TRUE ORIGINS 26 THE RED BOOK (1951) 26 OPERATION LUNA (1952) 27 DISINFORMATION: EMMET MOSEBY M.I.A. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Project # Category

Project # J0101 Category: Animal Biology - Jr Student: Amy Figueroa Grade: 8 G: F School: South Gate Middle School Title: Anemon-EATS My question is, "How can temperature change affect the eating habits of Actiniaria?" In my experiment, I feed Actiniaria in different seawater temperatures. The temperatures were 7,13, and 22 degrees Celsius. My hypothesis is: If the water temperature is lower than 13°C, the anemones will consume more to maintain their body temperatures. If my hypothesis is supported, this will emphasize the importance of protecting the planet. Global warming is not just warming the Earth but it is causing the Earth to experience extreme temperatures. There is a higher chance of consuming plastic with harmful chemicals that were not intended for digesting if they eat more. With higher water temperatures, body temperatures will also rise, meaning anemones will eat less. The independent variables of my experiment are the water temperatures. The dependent factors are my recorded data points which is how long it takes for them to react to food. All throughout my experiment, I kept the food and timer the same so I could get reliable data. I fed and timed them 50 different times in each water treatment. I saw the anemones react quicker in lower temperatures. This supports my hypothesis. A factor that could have affected my results was that some anemones might have not been hungry. I also observed the anemones had a delayed reaction in the warmest temperature. My experiment can be expanded in many ways but this will provide so much information on the effect of temperature change on the eating habits of Actiniaria. -

Columbia Poetry Review Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Poetry Review Publications Spring 4-1-2002 Columbia Poetry Review Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Poetry Review" (2002). Columbia Poetry Review. 15. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Poetry Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLUMBIA poetry review 1 3 > no. 15 $6.00 USA $9.00 CANADA o 74470 82069 7 COLUMBIA POETRY REVIEW Columbia College Chicago Spring 2002 Columbia Poetry Review is published in the spring of each year by the English Department of Columbia College, 600 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60605. Submissions are encouraged and should be sent to the above address from August 15 to January 1. Subscriptions and sample copies are available at $6.oo an issue in the U.S.; $9.00 in Canada and elsewhere. The magazine is edited by students in the un dergraduate poetry program and distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Periodicals. Copyright (c) 2002 by Columbia College. ISBN: 0-932026-59-1 Grateful acknowledgment is made to Garnett Kilberg-Cohen, Chair of the English Department; Dr. Cheryl Johnson-Odim, Dean of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Steven Kapelke, Provost; and Dr. -

February 2006

FREE January 2011 www.sandiegotroubadour.com Vol. 10, No. 4 what’s inside Welcome Mat ………3 Mission Contributors The Macaroni Club Brian Baynes Full Circle.. …………4 ’60 at 50 Recordially, Lou Curtiss Front Porch... ………6 Jazz Night at El Take It Easy Folding Mr. Lincoln Parlor Showcase …8 Michael Rennie Ramblin’... …………10 Bluegrass Corner Zen of Recording Hosing Down Radio Daze Stages Highway’s Song. …12 Robby Krieger Of Note. ……………13 The Heavy Guilt Christopher Dale Duo LaRé Skid Roper River City ‘Round About ....... …14 January Music Calendar The Local Seen ……15 Photo Page see it at Monica’s at the Park thru January, 1735 Adams Ave., University Heights JANUARY 2011 SAN DIEGO TROUBADOUR welcome mat RSAN ODUIEGBO ADOUR Come Together Alternative country, Americana, roots, folk, Tblues, gospel, jazz, and bluegrass music news by Will Edwards about what I’m supposed to be doing MISSION CONTRIBUTORS photos: Bryan Heil with my music.” After years of develop - ing, producing, and promoting his own To promote, encourage, and provide an FOUNDERS alternative voice for the great local music that Ellen and Lyle Duplessie hen there’s a will there is a music, Aaron switched gears. “My thing is generally overlooked by the mass media; Liz Abbott way... In a town brimming is to help people,” he says. namely the genres of alternative country, Kent Johnson with creative artists of every As is the case with many an artist, Americana, roots, folk, blues, gospel, jazz, and W PUBLISHERS description, Aaron and Kate Bowen saw a Aaron found his hometown to have its bluegrass. -

Financial Aid Explains • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • in an Interview That I Had with Mr

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Innovator Student Newspapers 1-17-1978 Innovator, 1978-01-17 Student Services Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/innovator Recommended Citation Governors State University Student Services, Innovator (1978, January 17). http://opus.govst.edu/innovator/114 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Innovator by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. One Hundred Dollars Reward Cnlyn Greer Robbery of several items occurred at G.S.U. during the Christmas break. The Dean of CCS, The Innovator and Paul Schranz's offices, were vandalized. Missing from the In novator was a typewriter, a camera which was the personal property of a student, a light meter, and a tape recorder. Taken from Paul Schranz's office was $1,400.00 worth of cameras and lighting systems. Strangely enough the robbers did not bother personal property of both professorBracken and professor Schranz. Various items were taken from the Dean of CCS office, including a clock. The robbery is not covered by insurance because according to Richard Strutters of the Business Office, "The state does not allow us to insure equipment." The items taken will have to be replaced from the budget somewhere and this willtake some time." Meanwhile the robberyhas hurt the students because they no longer have these items to learn from. A work-study job no longer exists becauseof damage to a dark room where a student worked. -

2 April 2021 Page 1 of 18 SATURDAY 27 MARCH 2021 Astrazeneca's CEO Faces Scrutiny As His Company's Vaccine, Presenter: Nikki Bedi and Its Roll Out, Comes Under Fire

Radio 4 Listings for 27 March – 2 April 2021 Page 1 of 18 SATURDAY 27 MARCH 2021 AstraZeneca's CEO faces scrutiny as his company's vaccine, Presenter: Nikki Bedi and its roll out, comes under fire. Mark Coles explores the life Presenter: Suzy Klein SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000tg6y) and career one of big pharma's biggest names. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. The oldest of four boys, Pascal Soriot grew up in a working class area of Paris. He took the helm at AZ in 2012 after years SAT 10:30 Mitchell on Meetings (m000tmpd) in top jobs across the world. One of his first challenges was to The Brainstorm SAT 00:30 One Two Three Four - The Beatles In Time by fight off a takeover from Pfizer. The AZ vaccine, currently not- Craig Brown (m000tg70) for-profit, was hailed as a life saver for millions. But with David Mitchell started the series as a meetings sceptic. Has he Episode 5 accusations of confusing drug trial data, dishonest dealings with been converted? In the last episode in the series, David is joined the EU and safety fears, has the AstraZeneca CEO lost his by Professor Margaret Macmillan to tackle one of history's Craig Brown presents a series of kaleidoscopic glimpses of The shine? biggest meetings - the 1919 Paris Conference. We learn there's Beatles through time. Drawing on interviews, diaries, anecdotes, Presenter: Mark Coles nothing new about management away-days or brainstorming memoirs and gossip, he offers an entertaining series of vignettes Researcher: Matt Murphy sessions - they were being used a hundred years ago. -

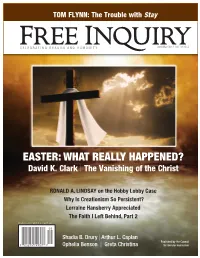

The Trouble with Stay

TOM FLYNN: The Trouble with Stay CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY April/May 2014 Vol. 34 No.3 EASTER: WHAT REALLY HAPPENED? David K. Clark | The Vanishing of the Christ RONALD A. LINDSAY on the Hobby Lobby Case Why Is Creationism So Persistent? Lorraine Hansberry Appreciated The Faith I Left Behind, Part 2 Introductory Price $4.95 U.S. / $4.95 Can. Shadia B. Drury | Arthur L. Caplan Published by the Council Ophelia Benson | Greta Christina for Secular Humanism April/May 2014 Vol. 34 No. 3 CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY Easter: What Really Happened? 16 Introduction 28 Why I Am Not a Member . of Anything Robert F. Allen Tom Flynn 17 Betting on Jesus: 30 Leaving Unholy Mother Church The Vanishing of the Christ William F. Nolan David K. Clark 31 Why Is Creationism So Persistent? The Faith I Left Behind, Part 2 Lawrence Wood 24 Why I Am Not a 38 Faith: A Disappearing Concept Fundamentalist Christian Mark Rubinstein Celeste Rorem 60 New Laureates Elected to 26 Why I Am Not a Muslim The Academy of Humanism Kylie Sturgess EDITORIAL LETTERS REVIEWS 4 To What Extent Should We 12 56 Stay: A History of Suicide and Accommodate Religious Beliefs? the Philosophies Against It Ronald A. Lindsay DEPARTMENTS by Jennifer Michael Hecht Reviewed by Tom Flynn 46 Church-State Update OP-EDS School Rankings and Vouchers: 7 Dead Is Dead Connecting the Dots 61 Just Babies: The Origins of Arthur L. Caplan Edd Doerr Good and Evil by Paul Bloom 8 What Would Happen If 48 Great Minds Reviewed by Wayne L.