Visionary Africa: Art & Architecture at Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Word of Welcome from the Conference Organizer

A word of welcome from the conference organizer Dear conference delegates, Welcome to the Nordic Africa Days 2014 in Uppsala! The Nordic Africa Days (NAD) is the biennial conference which for the past six years has been organized rotatively in each of the Nordic countries. Already since 1969 the Nordic Africa Institute has organised this regular gathering of Nordic scholars studying African issues, and the event has for the past 15 years been formalized under the name of the Nordic Africa Days. The theme of this year’s conference is Misbehaving States and Behaving Citizens? Questions of Governance in African States. We are proud to host two distinguished keynote speakers, Dr Mo Ibrahim and Associate Professor Morten Jerven, addressing the theme from different angles in their speeches entitled “Why Governance Matters” and “Africa by Numbers: Knowledge & Governance”. The conference is funded by long-standing and committed support from the Swedish, Finnish, Norwegian and Icelandic governments. This year, we are also particularly pleased to be able to facilitate participation of about 25 researchers based on the African continent through a generous contribution from Sida (The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency). Providing a platform for Nordic and African researchers to meet and cooperate at NAD is becoming ever more important, in addition to creating a prime meeting place for researchers on Africa within the Nordic region. The main conference venue is Blåsenhus, one of the newest campuses within Uppsala University, situated opposite the Uppsala Castle and surrounded by the Uppsala Botanical Gardens. This particular area of Uppsala has a historical past that goes back 350 years in time and offers many interesting places to visit. -

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 18:33 Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Résumé de l'article Volume 21, numéro 2, 2011 Cet article livre des réflexions générales sur quelques défis auxquels les compositeurs africains de musique de concert sont confrontés. Le point de URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar départ spécifique se trouve dans une anthologie qui date de 2009, Piano Music DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar of Africa and the African Diaspora, rassemblée par le pianiste et chercheur ghanéen William Chapman Nyaho et publiée par Oxford University Press. Aller au sommaire du numéro L’anthologie offre une grande panoplie de réalisations artistiques dans un genre qui est moins associé à l’Afrique que la musique « populaire » urbaine ou la musique « traditionnelle » d’origine précoloniale. En notant les avantages méthodologiques d’une approche qui se base sur des compositions Éditeur(s) individuelles plutôt que sur l’ethnographie, l’auteur note l’importance des Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal rencontres de Steve Reich et György Ligeti avec des répertoires africains divers. Puis, se penchant sur un choix de pièces tirées de l’anthologie, l’article rend compte de l’héritage multiple du compositeur africain et la façon dont cet ISSN héritage influence ses choix de sons, rythmes et phraséologie. Des extraits 1183-1693 (imprimé) d’oeuvres de Nketia, Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi et Osman servent d’illustrations à cet 1488-9692 (numérique) article. Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Agawu, K. -

Can African States Conduct Free and Fair Presidential Elections? Edwin Odhiambo Abuya

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 8 | Issue 2 Article 1 Spring 2010 Can African States Conduct Free and Fair Presidential Elections? Edwin Odhiambo Abuya Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Edwin Odhiambo Abuya, Can African States Conduct Free and Fair Presidential Elections?, 8 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 122 (2010). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol8/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2010 by Northwestern University School of Law Volume 8, Issue 2 (Spring 2010) Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Can African States Conduct Free and Fair Presidential Elections? Edwin Odhiambo Abuya* Asiyekubali kushindwa si msihindani.1 I. INTRODUCTION ¶1 Can African States hold free and fair elections? To put it another way, is it possible to conduct presidential elections in Africa that meet internationally recognized standards? These questions can be answered in the affirmative. However, in order to safeguard voting rights, specific reforms must be adopted and implemented on the ground. In keeping with international legal standards on democracy,2 the constitutions of many African states recognize the right to vote.3 This right is reflected in the fact that these states hold regular elections. The right to vote is fundamental in any democratic state, but an entitlement does not guarantee that right simply by providing for elections. -

Yale: Focus on Africa - Fall 2017

Yale: Focus on Africa - Fall 2017 SHARE: Join Our Email List In this edition of Focus on Africa we present an array of highlights showcasing notable speakers and visitors on campus, faculty news, student and alumni profiles and educational programs on the continent. We also bring you a snapshot of the various activities on campus that serve as an invaluable platform for substantive inquiry and discourse on Africa. Over the last few months, we have been pleased to welcome several alumni to campus, including renowned human rights lawyer Pheroze Nowrojee '74 LLM and novelist Deji Olukotun '00 B.A. We hope you enjoy this issue. - Eddie Mandhry, Director for Africa Faculty Research Faculty Awarded Two Grants to Support Health System in Liberia Faculty at the Yale School of Medicine have been awarded two grants by the World Bank and the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to support and strengthen medical education and health management in Liberia. The Yale Team will be led by Dr. Asghar Rastegar, professor of medicine and director of the Office of Global Health in the Department of Medicine, and will include Onyema Ogbuagu, assistant professor of infectious diseases, and Dr. Kristina Talbert-Slagle, assistant professor of general internal medicine. More >> Kate Baldwin Appointed the Strauss Assistant Professor of Political Science Kate Baldwin was newly named as the Peter Strauss Family Assistant Professor of Political Science. She focuses her research on political accountability, state building, and the politics of development, with a regional focus on sub-Saharan Africa. Baldwin is the author of the book https://myemail.constantcontact.com/Yale--Focus-on-Africa---Fall-2017.html?soid=1114503266644&aid=I29nYbCBV5o[6/17/21, 3:37:29 PM] Yale: Focus on Africa - Fall 2017 "The Paradox of Traditional Chiefs in Democratic Africa," which received an Honorable Mention for the Riker Award recognizing the best book in political economy published in the previous three years. -

Journal of African Elections

JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS Volume 17 Number 1 June 2018 remember to change running heads VOLUME 17 NO 1 i Journal of African Elections EDITOR Denis Kadima ARTICLES BY Zefanias Matsimbe Nelson Domingos John Rabuogi Ahere Moses Nderitu Nginya Adriano Nuvunga Joseph Hanlon Emeka C. Iloh Michael E. Nwokedi Cornelius C. Mba Kingsley O. Ilo Atanda Abdulwaheed Isiaq Oluwashina Moruf Adebiyi Adebola Rafiu Bakare Joseph Olusegun Adebayo Nicodemus Minde Sterling Roop Kjetil Tronvoll Volume 17 Number 1 June 2018 i ii JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS Published by EISA 14 Park Road, Richmond, Johannesburg, South Africa P O Box 740, Auckland Park, 2006, South Africa Tel: +27 (0) 11 381 6000 Fax: +27 (0) 11 482 6163 e-mail: [email protected] © EISA 2018 ISSN: 1609-4700 (Print) ISSN 2415-5837 (Online) v. 17 no. 1: 10.20940/jae/2018/v17i1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher Printed by: Corpnet, Johannesburg Cover photograph: Reproduced with the permission of the HAMILL GALLERY OF AFRICAN ART, BOSTON, MA, USA For electronic back copies of JAE visit www.eisa jae.org.za remember to change running heads VOLUME 17 NO 1 iii EDITOR Denis Kadima, EISA, Johannesburg MANAGING EDITOR Heather Acott EDITORIAL BOARD Chair: Denis Kadima, EISA, South Africa Cherrel Africa, Department of Political Studies, University of the Western Cape, South Africa Jørgen -

Lost Wax: an Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Kevin Bell SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2009 Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Kevin Bell SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Art Practice Commons Recommended Citation Bell, Kevin, "Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal" (2009). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 735. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/735 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Bell, Kevin Academic Director: Diallo, Souleye Project Advisor: Diop, Issa University of Denver International Studies Africa, Senegal, Dakar Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Senegal Arts and Culture, SIT Study Abroad, Fall 2009 Table of Contents ABSTRACT: ................................................................................................................................................................1 I. LEARNING GOALS: .........................................................................................................................................2 I. RESOURCES AND METHODS: ......................................................................................................................3 -

The State and Politicization of Governance in Post 1990 Africa:A

International Journal of Political Science (IJPS) Volume 2, Issue 2, 2016, PP 23-38 ISSN 2454-9452 http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-9452.0202003 www.arcjournals.org The State and Politicization of Governance in Post 1990 Africa: A Political Economy 1Luke Amadi, 2Imoh –Imoh-Itah, 3 Roger Akpan 1,3Department of Political and Administrative Studies, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria 2Department of Public Administration, Akwa Ibom State University, Obio Akpa Campus Abstract: Novel expectations for democratization re-emerged at the Post- Cold War Africa following the return to multi -party elections and the dismantling of one party authoritarian regime. What remains largely unclear and poorly studied is the dynamics of the State and Governance at Post -Cold War Africa .This paper deployed the Marxian political economy framework and examined the State and governance nexus in Africa’s nascent democracy in the period 1990 to 2014. It argued that the State in Africa remains increasingly elitist and predatory despite the end to one party autocratic regime and multi -party elections. The substantial strategy has been “the politicization of governance”. It conceptualized this theoretical model to demonstrate how the State and governance deploy coercive instrumentalities to appropriate political power . The salient dimensions are explored to demonstrate that the State has remained a “derisive apparatus” in naked pursuit of power. In particular, it demonstrates how political patronage is fought for, resisted or propagated and how this has increasingly resulted in failure of governance and development. Keywords: The State , Politics, Governance, Democracy, Development, Africa 1. INTRODUCTION Since the emergence of modern State, relationships and interactions among actors within the State orbit have ever been more important to explore the study of governance as a mode of theoretical and empirical inquiry and as activity of people in government. -

Global Heritage Assemblages and Modern Architecture in Africa

Rescuing Modernity: Global Heritage Assemblages and Modern Architecture in Africa Citation for published version (APA): Rausch, C. (2013). Rescuing Modernity: Global Heritage Assemblages and Modern Architecture in Africa. Universitaire Pers Maastricht. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20131018cr Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2013 DOI: 10.26481/dis.20131018cr Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Five Takes on African Art a Study Guide

FIVE TAKES ON AFRICAN ART A STUDY GUIDE TAKE 1 considers materiality, and the elements used to make aesthetic objects. It also considers the connections that materials have to the people who originally crafted them, and furthermore, their ties to new generations of crafters, interpreters, and collectors of African works. The objects in this collection challenge our notions of “African art” in that they were not formed for purely aesthetic purposes, but rather were created from raw, natural materials, carefully refined, and then skillfully handcrafted to serve particular needs in homes and communities. It is fascinating to consider that each object featured here bears a characteristic that identifies it as belonging to a distinct region or group of people, and yet is nearly impossible to unearth the narratives of the individual artists who created them. Through these works, we can consider the bridge between materiality and diaspora—objects of significance with “genetic codes” that move from one hand to the next, across borders, and oceans, with a dynamism that is defined by our ever-shifting world. Here, these “useful” objects take on a new function, as individual parts to an entire chorus of voices—each possessing a unique story in its creation and journey. What makes these objects ‘collectors’ items’? Pay close attention to the shapes, forms, and craftsmanship. Can you find common traits or themes? The curator talks about their ‘genetic codes’. Beside the object’s substance, specific to the location of its creation, it may carry traces of other accumulated materials, such as food, skin, fiber, or fluids. -

Contemporary Africa Arts

CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN ARTS MAPPING PERCEPTIONS, INSIGHTS AND UK-AFRICA COLLABORATIONS 2 CONTENTS 1. Key Findings 4 2. Foreword 6 3. Introduction 8 4. Acknowledgements 11 5. Methodology 12 6. What is contemporary African arts and culture? 14 7. How do UK audiences engage? 16 8. Essay: Old Routes, New Pathways 22 9. Case Studies: Africa Writes & Film Africa 25 10. Mapping Festivals - Africa 28 11. Mapping Festivals - UK 30 12. Essay: Contemporary Festivals in Senegal 32 13. What makes a successful collaboration? 38 14. Programming Best Practice 40 15. Essay: How to Water a Concrete Rose 42 16. Interviews 48 17. Resources 99 Cover: Africa Nouveau - Nairobi, Kenya. Credit: Wanjira Gateri. This page: Nyege Nyege Festival - Jinja, Uganda. Credit: Papashotit, commissioned by East Africa Arts. 3 1/ KEY FINDINGS We conducted surveys to find out about people’s perceptions and knowledge of contemporary African arts and culture, how they currently engage and what prevents them from engaging. The first poll was conducted by YouGov through their daily online Omnibus survey of a nationally representative sample of 2,000 adults. The second (referred to as Audience Poll) was conducted by us through an online campaign and included 308 adults, mostly London-based and from the African diaspora. The general British public has limited knowledge and awareness of contemporary African arts and culture. Evidence from YouGov & Audience Polls Conclusions Only 13% of YouGov respondents and 60% of There is a huge opportunity to programme a much Audience respondents could name a specific wider range of contemporary African arts and example of contemporary African arts and culture, culture in the UK, deepening the British public’s which aligned with the stated definition. -

Au Echo 2021 1 Note from the Editor

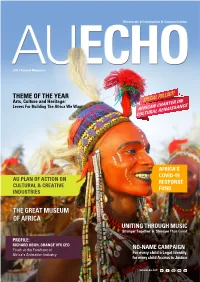

Directorate of Information & Communication 2021 Annual Magazine THEME OF THE YEAR Arts, Culture and Heritage: Levers For Building The Africa We Want AFRICAN CHARTER ON CULTURAL RENAISSANCE AFRICA’S COVID-19 AU PLAN OF ACTION ON RESPONSE CULTURAL & CREATIVE FUND INDUSTRIES THE GREAT MUSEUM OF AFRICA UNITING THROUGH MUSIC ‘Stronger Together’ & ‘Stronger Than Covid’ PROFILE: RICHARD OBOH, ORANGE VFX CEO Youth at the Forefront of NO-NAME CAMPAIGN Africa’s Animation Industry For every child a Legal Identity, for every child Access to Justice www.au.int AU ECHO 2021 1 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR he culture and creative industries (CCIs) generate annual global revenues of up to US$2,250 billion dollars and Texports in excess of US$250 billion. This sector currently provides nearly 30 million jobs worldwide and employs more people aged 15 to 29 than any other sector and contributes LESLIE RICHER up to 10% of GDP in some countries. DIRECTOR Directorate of Information & In Africa, CCIs are driving the new economy as young Africans Communication tap into their unlimited natural resource and their creativity, to create employment and generate revenue in sectors traditionally perceived as “not stable” employment options. taking charge of their destiny and supporting the initiatives to From film, theatre, music, gaming, fashion, literature and art, find African solutions for African issues. On Africa Day (25th the creative economy is gradually gaining importance as a May), the African Union in partnership with Trace TV and All sector that must be taken seriously and which at a policy level, Africa Music Awards (AFRIMA) organised a Virtual Solidarity decisions must be made to invest in, nurture, protect and grow Concert under the theme ‘Stronger Together’ and ‘Stronger the sectors. -

OCPA NEWS No174

Observatory of Cultural Policies in Africa The Observatory is a Pan African international non-governmental organization. It was created in 2002 with the support of African Union, the Ford Foundation and UNESCO with a view to monitor cultural trends and national cultural policies in the region and to enhance their integration in human development strategies through advocacy, information, research, capacity building, networking, co-ordination and co-operation at the regional and international levels. OCPA NEWS No174 O C P A 12 February 2007 This issue is sent to 8485 addresses * VISIT THE OCPA WEB SITE http://www.ocpanet.org * 1 Are you planning meetings, research activities, publications of interest for the Observatory of Cultural Policies in Africa? Have you heard about such activities organized by others? Do you have information about innovative projects in cultural policy and cultural development in Africa? Do you know interesting links or e-mail address lists to be included in the web site or the listserv? Please send information and documents for inclusion in the OCPA web site! * Thank you for your co-operation. Merci de votre coopération. Máté Kovács, editor: [email protected] *** New Address: OCPA Secretariat 725, Avenida da Base N'Tchinga, Maputo, Mozambique Postal address; P. O. Box 1207 E-mail: [email protected] or Lupwishi Mbuyamba, director: [email protected] *** You can subscribe to OCPA News via the online form at http://ocpa.irmo.hr/activities/newsletter/index-en.html. Vous pouvez vous abonner ou désabonner à OCPA News, via le formulaire disponible à http://ocpa.irmo.hr/activities/newsletter/index-fr.html * Previous issues of OCPA News are available at Lire les numéros précédents d’OCPA News sur le site http://www.ocpanet.org/ 2 ××× In this issue – Dans ce numéro A.