SUNDAY 6Pm PST VERSION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTRODUCED CORELLA ISSUES PAPER April 2014

INTRODUCED CORELLA ISSUES PAPER April 2014 City of Bunbury Page 1 of 35 Disclaimer: This document has been published by the City of Bunbury. Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this document is made in good faith and on the basis that the City of Bunbury, its employees and agents are not liable for any damage or loss whatsoever which may occur as a result of action taken or not taken, as the case may be, in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to herein. Information pertaining to this document may be subject to change, and should be checked against any modifications or amendments subsequent to the document’s publication. Acknowledgements: The City of Bunbury thanks the following stakeholders for providing information during the drafting of this paper: Mark Blythman – Department of Parks and Wildlife Clinton Charles – Feral Pest Services Pia Courtis – Department of Parks and Wildlife (WA - Bunbury Branch Office) Carl Grondal – City of Mandurah Grant MacKinnon – City of Swan Peter Mawson – Perth Zoo Samantha Pickering – Shire of Harvey Andrew Reeves – Department of Agriculture and Food (WA) Bill Rutherford – Ornithological Technical Services Publication Details: Published by the City of Bunbury. Copyright © the City of Bunbury 2013. Recommended Citation: Strang, M., Bennett, T., Deeley, B., Barton, J. and Klunzinger, M. (2014). Introduced Corella Issues Paper. City of Bunbury: Bunbury, Western Australia. Edition Details: Title: Introduced Corella Issues Paper Production Date: 15 July 2013 Author: M. Strang, T. Bennett Editor: M. Strang, B. Deeley Modifications List: Version Date Amendments Prepared by Final Draft 15 July 2013 M. -

Cockatiels Free

FREE COCKATIELS PDF Thomas Haupt,Julie Rach Mancini | 96 pages | 05 Aug 2008 | Barron's Educational Series Inc.,U.S. | 9780764138966 | English | Hauppauge, United States How to Take Care of a Cockatiel (with Pictures) - wikiHow A cockatiel is a popular choice for a pet bird. It is a small parrot with a variety of color patterns and a head crest. They are attractive as well as friendly. They are capable of mimicking speech, although they can be difficult to understand. These birds are good at whistling and you can teach them to sing along to tunes. Life Expectancy: 15 to 20 years with proper care, and sometimes as Cockatiels as 30 years though this is rare. In their native Australia, cockatiels are Cockatiels quarrions or weiros. They primarily live in the Cockatiels, a region of the northern part of the Cockatiels. Discovered inthey are the smallest members of the cockatoo family. They exhibit many of the Cockatiels features and habits as the larger Cockatiels. In the wild, they live in large flocks. Cockatiels became Cockatiels as pets during the s. They are easy to breed in captivity and their docile, friendly personalities make them a natural fit for Cockatiels life. These birds can Cockatiels longer be trapped and exported from Australia. These little birds are gentle, affectionate, and often like to be petted and held. Cockatiels are not necessarily fond of cuddling. They simply want to be near you and will be very happy to see you. Cockatiels are generally friendly; however, an untamed bird might nip. You can prevent bad Cockatiels at an early age Cockatiels ignoring bad behavior as these birds aim to please. -

The Avicultural Society of New South Wales Inc. (ASNSW) Black Cockatoos

The Avicultural Society of New South Wales Inc. (ASNSW) (Founded in 1940 as the Parrot & African Lovebird Society of Australia) Black Cockatoos (ASNSW The Avicultural Review - Volume 15 No. 3 April/May 1993) Among the most fascinating and majestic of our birds are the black cockatoos. The six species that fall into this descriptive group have colonised almost every area of Australia, adapting to a wide range of climates and landscapes. Few sights are more rewarding to the naturalist than seeing a party of these birds circling and wheeling high in the air, before descending on a stand of eucalypts or casuarinas. Introduction The black cockatoos are divided into three genera — Probisciger, Calyptorhynchus and Callocephalon. All are characterised by a dark or black body, strong beak and legs and feet well adapted for gripping. Nesting is carried out high in a tree, in a hollow limb, where one or two eggs are laid. Incubation is undertaken by the female, who is fed by the male during her time at the nest. The young, when they hatch, are naked and helpless, and will stay in the nest for about 10-12 weeks before venturing into the outside world. Large numbers of black cockatoos were taken for the pet trade before controls were introduced. Generally, the young were removed from the nest and raised by hand. If the nest was inaccessible, then the whole tree was cut down — a practice which effectively diminished the supply of nesting sites for future seasons. Today, the black cockatoos are fully protected, but destruction of habitat is still a threat as more areas are cleared for agriculture. -

Cockatiels by Catherine Love, DVM Updated 2021

Cockatiels By Catherine Love, DVM Updated 2021 Natural History Cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus) are a species of small-medium parrots native to arid regions of Australia. They are the smallest members of the cockatoo family and the only species in their genus. Wild cockatiels live in small groups or pairs, but large flocks may gather around a single water source. These birds prefer relatively open environments, including dry grasslands and sparse woodlands. They are nomadic, traveling great distances to forage for food and water. Cockatiels are the most popular pet bird in the US, and one of the most popular pet birds in the world. They are considered “Least Concern” by the IUCN. Characteristics and Behavior Cockatiels are cute, charismatic, and relatively small. This makes them desirable in the pet trade. Wild-type cockatiels are grey with a yellow head and orange-red cheeks, but there are numerous morphs that have been developed in captivity. Cockatiels possess a set of long feathers on their head called a crest, which will change position in response to their mood. Alert or curious birds will stick their crest straight up, whereas defensive birds will flatten their crest to their head and hiss with an open beak. Cockatiels generally bond strongly with their owner, but often do not take well to strangers. Rather than squawking, cockatiels tend to whistle and chirp. Males are known to be more inclined to talk or whistle than females, but both sexes can learn to mimic sounds to some extent. Cockatiels are generally considered quieter than many other parrot species, but they are still capable of making a great deal of noise. -

Western Australian Bird Notes Quarterly Newsletter of the Western Australian Branch of Birdlife Australia No

Western Australian Bird Notes Quarterly Newsletter of the Western Australian Branch of BirdLife Australia No. 143 September 2012 Our Great Western Woodlands. See article, page 4. birds are in our nature Mulga Parrot, Eyre Mistletoebird at a (see report p34). nightshade plant see Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo, Twin Creeks Photo by Malcolm report p16). Photo Reserve, Albany (see report, p28). Photo by John and Fay Abbott by Barry Heinrich Dart First year Western Gerygone (see report, p18). Photos by Bill Rutherford The moult limit in the greater No moult limit is detectable in coverts of this 1st year Western this 1st year Western Gerygone Gerygone is discernible by the but note the contrast in the Shelduck duckling on longer length of greater coverts feather colour of the tertials its way to earth (see 1 and 2. and secondaries. report p23). Photo by John Nilson See corella report p22. Tags such as these are being used to help track corella movements. Photo by Jennie Corella wing tags are easy to spot, and are helping us learn about Stock flock movements. Photos by Jennie Stock Front cover (clockwise): 1. Gilbert’s Whistler, a species which has had a contraction of range in the wheatbelt, but still occurs in the Great Western Woodlands. Photo by Chris Tzaros (2) Woodlands in the vicinity of the Helena and Aurora Range. Photo by Cheryl Gole (3) Location of the Great Western Woodlands. See report, page 4 Page 2 Western Australian Bird Notes, No. 143 September 2012 Executive Committee 2012 Western Australian Branch of Chair: Suzanne Mather holds this position and was elected at BirdLife Australia the AGM in 2011. -

Cockatoo Care Introduction and Species Cockatoos Are a Very

[email protected] http://www.aeacarizona.com Address: 7 E. Palo Verde St., Phone: (480) 706-8478 Suite #1 Fax: (480) 393-3915 Gilbert, AZ 85296 Emergencies: Page (602) 351-1850 Cockatoo Care Introduction and Species Cockatoos are a very diverse group of birds, comprising five genuses. Members include (with currently recognized subspecies): Ducorp’s, Galah, Gang-gang, Goffin’s, Major Mitchell’s, Palm, Philippine Red-vented, Red-tailed, Salmon-crested Moluccan, Long-billed Corella, Glossy, Blue-eyed, Black (Funereal and White-tailed), White Umbrella, Little Corella (Bare-eyed and Sanguinea Sanguinea), Lesser Sulfur-crested (Sulphurea Sulphurea and Citron-crested), and Greater Sulfur-crested (Galerita Galerita–GG, Fitzroyi–F, Triton–T, and Eleonora–E). To further confuse the issue, many of these species and sub-species have more than one common name (i.e. Major Mitchell’s = Leadbeater), or will be recognized by only part of it (White Umbrella = White or Umbrella). They can be white with various touches of yellow, pink, or orange in the crest; or black with touches of pink, red, yellow, or white in body, head, or tail feathers. Sizes range from 12 to 28 inches from head to tip of tail. Some are very endangered, while others are considered pests in their native lands. Fortunately (or unfortunately), many of these species are not commonly encountered here in the United States as pets, so further discussion will only involve the six more common species: Moluccan, Umbrella, Bare-eyed, Goffin’s, Lesser-crested, and Greater-crested Cockatoos. • The Moluccan is a large white bird (20 inches) with a pinkish feather tinge, particularly in its large crest, and a black beak. -

Observations of Behaviour of Sulphur-Crested

OSEAIOS O EAIOU O SUUCESE COCKAOOS Ct lrt I SUUA SYEY KAREN BAYLY prtnt f ll Sn, Mr Unvrt, Sth Wl, Atrl 20 Received: 21 August 1998 A ppltn f Slphrrtd Ct Ct lrt t Ahfld, Sth Wl, brvd vr fr r prd. h brd r ntntnll hbttd t hn brvr nd ntt th hn ptvl rnfrd. h hbttn pr lld bhvr pttrn t b brvd t dtn f 0. hh lr thn thr td n frrnn Slphrrtd Ct. v prvl ndrbd bhvr pttrn r ntd — pr bln, pn, ll bln, ll llprnn nd hrn. h rthp dpl dffrd trnl fr prv drptn. Othr brvd bhvr pttrn r lr t prv drptn fr Ct p. INTRODUCTION shops, major roads and quiet suburban streets. However, there is a considerable amount of 'green space' in the form of parks and Considering that the Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Ct churchyards where a number of native trees, predominantly Eucalyptus lrt common bird, there have been surprisingly few haemostoma and Syncarpia glomulifera, have been preserved. published studies on its behaviour. To date, the major In addition, numerous native plants, including Melaleuca spp., descriptive work on the social and vocal behaviour of wild Callistemon spp. and Grevillea spp., have been planted as street trees, populations of these birds was carried out by Noske (1982) and many residents' gardens contain a variety of fruit and nut-bearing as part of an investigation into the pest status of Sulphur- species such as plane trees Plantanus spp., cypress Cupressus spp. and camphor laurel Cinnamonum camphora. crested Cockatoos on agricultural crops. -

How Cockatoos Evolved Is the Cockatiel a Member of the Cockatoo Family? by Linda S

How Cockatoos Evolved Is the Cockatiel a Member of the Cockatoo Family? By Linda S. Rubin RESEARCH STUDY Researchers at the University INTRODUCTION of California at Davis; David M. In the discussion of cocka- Brown, a Ph.D. student at UCLA; too evolution, it appears a long and Dr. Catherine A. Toft, pro- debate has been answered that fessor at the Center for Popula- would shed light on the cocka- tions Biology at UC Davis, con- too’s family structure, including ducted the study, “A Cockatoo’s the order and relationship of var- Who’s Who: Determining Evo- ious genera to one another and lutionary Relationships Among just how closely they are related. the Cockatoos.” The study was Pivotal to this exploration and published in volume 11, No. 2 of an adjunct to the question of the Exotic Bird Report in the Psit- cockatoo ancestry is whether the tacine Research Project of the Australian Cockatiel is an actual Department of Avian Sciences member of the cockatoo family. at the University of California at This is an important question Davis, and highlighted intrigu- not limited to cockatiel enthusi- ing new findings. asts. Should it be found that the © avian resources/steve Duncan To start, Brown and Toft Red-tailed Black Cockatoo cockatiel is indeed a cockatoo— acknowledged a lengthy history and the genera to which it is of the exhaustive work by other related is identified—perhaps some par- reproduction and various health issues researchers identifying 350 species of par- allels might be drawn that could prove (for example, weight gain can prompt a rots, beginning with Linnaeus in 1758, beneficial to cockatoo culture at large, or propensity for growing tumors and other and which revealed the following facts to some species of the cockatoo family. -

The Land of Cockatoos

As a breeder specializing in cocka The tour group consisted of ten toos, I was greatly excited by the people including the Monarch guide, The Land announcement in th~ Jun/Jul issue of Bill Martin, a long-time Australian Watchbird regarding Terra Psitta park ranger. His contacts and know corum, The Land of Parrots. This was ledge of the parks we visited were to of a tour conducted by Monarch Tours, add greatly to the success of the trip. of Australia. It was to visit many The people on the tour were all Cockatoos birding areas, bird attractions and Americans, ranging from parrot Australian breeders. fanciers to bird watchers of the Audu by Eric Nolan I contacted Monarch immediately, bon persuasion. One couple raised Brownsburg, Indiana not being able to wait for the "further show chickens and wallabies. Most information" promised for the were from California, but Seattle, OJ following issue. I signed up, but to my Pennsylvania, and Indiana (myself) c :J disappointment, the tour was can were also represented. o en celled due to several factors beyond OJ The trip was oriented primarily to .f6c the control of Monarch. They were, the national parks along the east .cro however, able to offer me an alter coast of Australia. We began with o > nate selection. I signed on for their Lamington ational Park in the hills .0 o birding and wildlife trip scheduled (5 above the Gold Coast, just south of .c 0... for early October. I also started Brisbane. After a flight north to dropping none too subtle hints in my Townsville, the tour spent several contacts with Monarch, that the spot days in the Atherton Tablelands ting of cockatoos in the wild was my before visiting Cairns and spending a idea ofan Australian wildlife outing. -

Forest Black Cockatoo (Baudin’S Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus Baudinii and Forest Red- Tailed Black Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus Banksii Naso) Recovery Plan 2007 – 2016

Forest Black Cockatoo (Baudin’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus baudinii and Forest Red- tailed Black Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus banksii naso) Recovery Plan 2007 – 2016 Wildlife Management Program No. 42 WESTERN AUSTRALIAN WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT PROGRAM NO. 42 FOREST BLACK COCKATOO (BAUDIN’S COCKATOO Calyptorhynchus baudinii AND FOREST RED-TAILED BLACK COCKATOO Calyptorhynchus banksii naso) RECOVERY PLAN 2007 – 2016 January 2007 Department of Environment and Conservation Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre WA 6983 i. FOREWORD Recovery Plans are developed within the framework laid down in Department of Environment and Conservation Policy Statements Nos 44 and 50. Recovery Plans outline the recovery actions that are required to address those threatening processes most affecting the ongoing survival of threatened taxa or ecological communities, and begin the recovery process. Recovery Plans delineate, justify and schedule management actions necessary to support the recovery of threatened species and ecological communities. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds necessary to implement actions is subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery Plans do not necessarily represent the views or the official position of individuals or organisations represented on the Recovery Team. This Recovery Plan was approved by the Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia. Approved Recovery Plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in status of the taxon or ecological community and the completion of recovery actions. The provision of funds identified in this Recovery Plan is dependent on budgetary and other constraints affecting the Department, as well as the need to address other priorities. -

Chbird 21 Previous Page, a Blue and Yellow Macaw (Ara Ararauna)

itizing Watch Dig bird Parrots in Southeast Asian Public Collections Aviculture has greatly evolved during the past 50 years, from keeping a collection of colorful birds to operating captive breeding programs to sustain trade and establish a viable captive population for threatened species. Many bird families are now fairly well represented in captivity, but parrots have a special place. Story and photography by Pierre de Chabannes AFA Watchbird 21 Previous page, a Blue and Yellow Macaw (Ara ararauna). Above, a bizarre version of a Black Lory, maybe Chalcopsitta atra insignis. hat makes parrots so attractive colorful species to be found there and the Southeast Asia, the Philippines and the four to both professional breeders, big areas of unexplored forests, both inland main Islands of western Indonesia, namely Wbirdwatchers and zoo visitors is and insular, that could provide the discov- Borneo, Sumatra, Java and Bali, along with a combination of many factors, including erer with many new bird varieties like it did their satellite islands. Here, the forests are their bright colors, their conspicuousness, recently in Papua New Guinea. mostly to be qualifi ed as tropical wet rain- their powerful voice coupled with complex Th e diversity and distribution of parrots forests with a much more humid climate behaviour that allows them to be spotted in this region follows a pattern described throughout the year and less important sea- easily in the fi eld and, most important of all, by Alfred Russel Wallace in the 19th Cen- sonal variations. their ability to interact with humans and tury with the clear separation from the Finally, Wallacea is really a transitional even “learn” new kinds of behaviours from Asian and the Australian zoogeographical zone which has characteristics of both Asian them. -

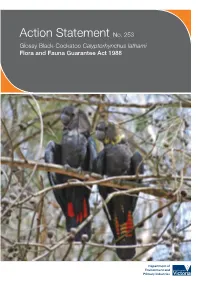

Action Statement No

Action Statement No. 253 Glossy Black-Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus lathami Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, Department of Environment and Primary Industries, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne, December 2013 © The State of Victoria Department of Environment and Primary Industries 2013 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Print managed by Finsbury Green December 2013 ISBN 978-1-74326-682-3 (Print) ISBN 978-1-74326-683-0 (pdf) Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please telephone DEPI Customer Service Centre 136186, email [email protected], via the National Relay Service on 133 677 www.relayservice.com.au This document is also available on the internet at www.depi.vic.gov.au Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Cover photo: Glossy Black-Cockatoo pair (Jill Dark) Action Statement No. 253 Glossy Black-Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus lathami Description Distribution The Glossy Black-Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami The Glossy Black-Cockatoo is endemic to mainland Australia (Christidis and Boles 2008)) is the smallest of the black- (Higgins 1999). Schodde et al. (1993) and Higgins (1999) cockatoos, reaching 48 cm in length.