Adopting a New Homeland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Travel Ban to Be Lifted

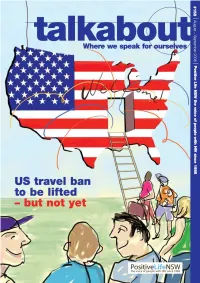

US travel ban to be lifted - ••ut not yet '2 <: 2 ;j :) ~ ...J L1 < :a > no.158 August - September 2008 res 2 Editorial 3 US ban to be lifted 4 Happy Birthday HIV 6 When less is more 7 Too far gone? 8 Behind the land of smiles: Thailand 12 A warm welcome: Kate from Poz Het 14 Prevention beyond condoms: Cover Artwork: Microbicides James Gilmour www.jamespgilmour.com 16 Coming from the space of true love Contributors: James Gilmour, Lance Feeney, Neal Drinnan, 18 Need to talk to someone? Greg Page, Rob Sutherland, Kate Reakes, Kathy Triffit, Kerry Saloner, Trevor Morris, Garry Wotherspoon, Leslie, Kane Matthews, Counselling at ACON John Douglas, Ingrid Cullen, Tim Alderman 20 Dry mouth and HIV 22 It's all in the mind? Mental health 24 Olga's Personals 26 Keeping on being positive: friendships through 729 27 Fear is high, trust is low: Positive sex workers 28 Buenos Aires 30 Working out at home: Health and fitness 32 Comfort food: So can you cook? Talkabout 1 PositiveL t .. NSW the voiceof people with HIV since 1 ~ In this issue CURRENT BOARD President Jason Appleby Vice President Richard Kennedy Treasurer Bernard Kealey Secretary Russell Westacott Directors Rob Lake, Malcolm Leech, Scott Berry, David Riddell, Alan Creighton Staff Representative Hedimo Santana Our cover highlights the welcome news Changes to the time out room Chief Executive Officer (Ex Officio) about changes in the US government's Positive Life NSW has been running the Rob take attitude to HIV positive visitors. We're not CURRENT STAFF time out room at the Mardi Gras (and quite there yet but, as the article on page Chief Executive Officer Rob take usually the Sleaze) Parties for about a three shows, the US is getting closer to a Manager Organisation and Team decade and a half now. -

Etix VVK Stellen

Altenburg Ticketgalerie GmbH Kornmarkt 1 D-04600 Bad Brückenau Mediengruppe Oberfranken Ludwigstraße 12 D-97769 Bad Kissingen Mediengruppe Oberfranken Theresienstr. 21 D-97688 Bad König Reisebüro Reisefenster Bahnhofstraß 12 D-64732 Bad Langensalza KTL Kur und Tourismus Bad Langensalza GmbH Bei der Marktkirche D-99947 Bad Liebenwerda Reisebüro Jaich Rossmarkt 5 D-04924 Bad Liebenwerda Wochenkurier Markt 16 D-04924 Bad Mergentheim Fränkische Nachrichten Verlags GmbH Kapuzinerstraße 4 (am Schloss) D-97980 Bad Salzungen Abokarten Verwaltungs GmbH BT Andreasstr. 11 D-36433 Bamberg bvd Kartenservice Lange Str. 39/41 D-96047 Bamberg Kartenkiosk Bamberg Forchheimer Str. 15 D-96050 Bamberg Mediengruppe Oberfranken Hauptwachstr. 22 D-96047 Bamberg Mediengruppe Oberfranken Gutenbergstr. 1 D-96050 Bamberg Mediengruppe Oberfranken Gutenbergstraße 1 D-96050 Bautzen Intersport Goschwitzstraße 2 D-02625 Bautzen SZ Bautzen Lauengraben 18 D-02625 Bautzen Wochenkurier Hauptmarkt 7 D-02625 Bayreuth Abokarten Verwaltungs GmbH BT - Nordbayerischer Kurier Theodor-Schmidt-Str. 17 D-95448 Bayreuth Theaterkasse Bayreuth Opernstraße 22 D-95444 Berlin Berliner KartenKontor im Forum Steglitz Schloßstr.1 D-12163 Berlin HOLIDAY LAND Reisebüro & Theaterkasse Schnellerstrasse 21 D-12439 Berlin Reisestudio Menzer Treskowallee 86 D-10318 Bitterfeld Reisebüro Bier Brehnaer Straße 34 D-06749 Borna Ticketgalerie GmbH Brauhausstraße 3 D-04552 Bremen Bremer KartenKontor bei Saturn in der Galeria Kaufhof Papenstr. 5 D-28195 Bremen Bremer Kartenkontor Zum Alten Speicher 9 D-28759 -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Leonard Bernstein

chapter one Young American Bernstein at Harvard In 1982, at the age of sixty-four, Leonard Bernstein included in his col- lection of his writings, Findings, some essays from his younger days that prefi gured signifi cant elements of his later adult life and career. The fi rst, “Father’s Books,” written in 1935 when he was seventeen, is about his father and the Talmud. Throughout his life, Bernstein was ever mind- ful that he was a Jew; he composed music on Jewish themes and in later years referred to himself as a “rabbi,” a teacher with a penchant to pass on scholarly learning, wisdom, and lore to orchestral musicians.1 Moreover, Bernstein came to adopt an Old Testament prophetic voice for much of his music, including his fi rst symphony, Jeremiah, and his third, Kaddish. The second essay, “The Occult,” an assignment for a freshman composi- tion class at Harvard that he wrote in 1938 when he was twenty years old, was about meeting Dimitri Mitropoulos, who inspired him to take up conducting. The third, his senior thesis of April 1939, was a virtual man- ifesto calling for an organic, vernacular, rhythmically based, distinctly American music, a music that he later championed from the podium and realized in his compositions for the Broadway stage and operatic and concert halls.2 8 Copyrighted Material Seldes 1st pages.indd 8 9/15/2008 2:48:29 PM Young American / 9 EARLY YEARS: PROPHETIC VOICE Bernstein as an Old Testament prophet? Bernstein’s father, Sam, was born in 1892 in an ultraorthodox Jewish shtetl in Russia. -

Frauenleben in Magenza

www.mainz.de/frauenbuero Frauenleben in Magenza Porträts jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen aus dem Mainzer Frauenkalender seit 1991 und Texte zur Frauengeschichte im jüdischen Mainz Frauenleben in Magenza Frauenleben in Magenza Die Porträts jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen aus dem Mainzer Frauenkalender und Texte zur Frauengeschichte im jüdischen Mainz 3 Frauenleben in Magenza Impressum Herausgeberin: Frauenbüro Landeshauptstadt Mainz Stadthaus Große Bleiche Große Bleiche 46/Löwenhofstraße 1 55116 Mainz Tel. 06131 12-2175 Fax 06131 12-2707 [email protected] www.mainz.de/frauenbuero Konzept, Redaktion, Gestaltung: Eva Weickart, Frauenbüro Namenskürzel der AutorInnen: Reinhard Frenzel (RF) Martina Trojanowski (MT) Eva Weickart (EW) Mechthild Czarnowski (MC) Bildrechte wie angegeben bei den Abbildungen Titelbild: Schülerinnen der Bondi-Schule. Privatbesitz C. Lebrecht Druck: Hausdruckerei 5. überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage Mainz 2021 4 Frauenleben in Magenza Vorwort des Oberbürgermeisters Die Geschichte jüdischen Lebens und Gemein- Erstmals erschienen ist »Frauenleben in Magen- delebens in Mainz reicht weit zurück in das 10. za« aus Anlass der Eröffnung der Neuen Syna- Jahrhundert, sie ist damit auch die Geschichte goge im Jahr 2010. Weitere Auflagen erschienen der jüdischen Frauen dieser Stadt. 2014 und 2015. Doch in vielen historischen Betrachtungen von Magenza, dem jüdischen Mainz, ist nur selten Die Veröffentlichung basiert auf den Porträts die Rede vom Leben und Schicksal jüdischer jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen und auf den Frauen und Mädchen. Texten zu Einrichtungen jüdischer Frauen und Dabei haben sie ebenso wie die Männer zu al- Mädchen, die seit 1991 im Kalender »Blick auf len Zeiten in der Stadt gelebt, sie haben gelernt, Mainzer Frauengeschichte« des Frauenbüros gearbeitet und den Alltag gemeistert. -

How Britain Unified Germany: Geography and the Rise of Prussia

— Early draft. Please do not quote, cite, or redistribute without written permission of the authors. — How Britain Unified Germany: Geography and the Rise of Prussia After 1815∗ Thilo R. Huningy and Nikolaus Wolfz Abstract We analyze the formation oft he German Zollverein as an example how geography can shape institutional change. We show how the redrawing of the European map at the Congress of Vienna—notably Prussia’s control over the Rhineland and Westphalia—affected the incentives for policymakers to cooperate. The new borders were not endogenous. They were at odds with the strategy of Prussia, but followed from Britain’s intervention at Vienna regarding the Polish-Saxon question. For many small German states, the resulting borders changed the trade-off between the benefits from cooperation with Prussia and the costs of losing political control. Based on GIS data on Central Europe for 1818–1854 we estimate a simple model of the incentives to join an existing customs union. The model can explain the sequence of states joining the Prussian Zollverein extremely well. Moreover we run a counterfactual exercise: if Prussia would have succeeded with her strategy to gain the entire Kingdom of Saxony instead of the western provinces, the Zollverein would not have formed. We conclude that geography can shape institutional change. To put it different, as collateral damage to her intervention at Vienna,”’Britain unified Germany”’. JEL Codes: C31, F13, N73 ∗We would like to thank Robert C. Allen, Nicholas Crafts, Theresa Gutberlet, Theocharis N. Grigoriadis, Ulas Karakoc, Daniel Kreßner, Stelios Michalopoulos, Klaus Desmet, Florian Ploeckl, Kevin H. -

Betreuungsangebote - Nach § 45A (1) Nr

Angebote zur Unterstützung im Alltag - Betreuungsangebote - nach § 45a (1) Nr. 1 SGB XI Landkreis Ort Institution Strasse PLZ E-Mail Telefon Altenburger Land Altenburg AWO KV Altenburger Land e.V. "Selbständiges Humboldtstraße 12 04600 selbst.wohnen.abg@awo- 03447/558998 Wohnen im Alter" thueringen.de Altenburger Land Altenburg Gemeinschaftspraxis für Ergotherapie Katrin Jenke Gabelentzstr. 6c 04600 [email protected] 03447/895464 & Kati Kratzsch Altenburger Land Altenburg Horizonte Altenburg gGmbH Carl von Ossietzky Str. 04600 verwaltung@horizonte- 03447/514212 19 altenburg.de Altenburger Land Rositz Familienentlastender und unterstützender Dienst Parkstr. 1 4617 [email protected] 034498/819263 der Lebenshilfe Altenburg Eichsfeld Heiligenstadt Kath. Altenheime Eichsfeld gGmbH Hospitalstraße 1 37308 [email protected] 03606/661445 Eichsfeld Leinefelde - Lebenshilfe Worbis e.V. Ernemannstr. 6 37327 m.toepfer@lebenshilfe- 03605/200993 Worbis worbis.de Eichsfeld Marth Betreuungsdienst "Mit Freude am Leben" Am Anger 1 37318 betreuungsdienst- [email protected] 036081/61325 Erfurt Erfurt Schutzbund der Senioren und Vorrhuheständler Juri-Gagarin-Ring 64 99084 landesverband@seniorenschut 0361/2620735 Thüringen e.V. zbund.org Erfurt Erfurt Volkssolidarität Thüringen gGmbH Sozialstation O.-Schlemmer-Str. 1 99085 thueringen- 0361/654770 Erfurt [email protected] Erfurt Erfurt Deutschordens-Seniorenhaus gGmbH Sozialstation Vilniuser Str. 14 99089 [email protected] 0361-7720 Erfurt Erfurt Caritas Trägergesellschaft "St. Elisabeth" gGmbH Herderstraße 5 99096 st.elisabeth-erfurt@caritas- 0361/34460 Altenpflegezentrum cte.de Erfurt Erfurt Altenhilfe Sophienhaus gGmbH Martin-Luther- Blosenburgstr. 19 99096 [email protected] 0361/60068153 Haus Erfurt Erfurt Christophoruswerk Erfurt gGmbH - Ambulanter Allerheiligenstr. 8 99084 betreuungsdienst@christophor 0361/21001-550 Betreuungsdienst uswerk.de Erfurt Erfurt MIA, (Miteinander-Inklusiv-Anders), offene Brühler Str. -

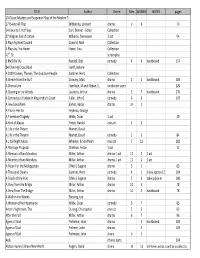

TAG SCRIPT LIBRARY Nov 2013.Xlsx

TITLE Author Genre Men WOMEN NOTES pages 10 Classic Mystery and Suspense Plays of the Modern T 1776‐And All That Wibberley, Leonard drama 98 70 24 Favorite 1 Act Plays Cerf, Bennet ‐ Editor Collection 27 Wagons Full of Cotton Williams, Tennessee 1 act 54 3 Plays by Noel Coward Coward, Noel Collection 3 Plays by Tina Howe Howe, Tina Collection 42nd St. screenplay 6 RMS RIV VU Randall, Bob comedy 4 4 hardbound 157 84 Charring Cross Road Hanff, Helene A 1000 Clowns, Thieves, The Goodbye People Gardner, Herb Collection A Breeze from the Gulf Crowley, Mart drama 2 1 hardbound 184 A Chorus Line Hamlisch, M.and Kleban, E, . conductor score 220 A Clearing in the Woods Laurents, Arthur drama 5 5 hardbound 170 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Fuller, John G. comedy 6 6 147 A Few Good Men Sorkin, Aaron drama 14 1 A Flea in Her Ear Feydeau, George A Florentine Tragedy Wilde, Oscar 1 act 20 A Kind of Alaska Pinter, Harold one act 1 2 A Life in the Theare Mamet, David A Life in the Theatre Mamet, David comedy 2 0 84 A Little Night Music Wheeler, & Sondheim musical 7 11 182 A Marriage Proposal Chekhov, Anton 1 act 12 A Memory of two Mondays Miller, Arthur drama‐1 act 12 2 1 act A Memory of two Mondays Miller, Arthur drama‐1 act 12 2 1 act A Moon For the Misbegotten O'Neill, Eugene drama 3 1 83 A Thousand Clowns Gardner, Herb comedy 4 1 1 boy approx 12 104 A Touch of the Poet O'Neill, Eugene drama 7 3 takes place in 180 A View from the Bridge Miller, Arthur drama 10 3 78 A View From The Bridge Miller, Arthur drama 10 3 hardbound 78 A Walk -

Assisted by Katie Rowan, Accompanist

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Morgan Robertson & Ellie Wise Junior Voice Recital assisted by Katie Rowan, Accompanist Tuesday, April 9, 2013 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performers. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert. Please turn off all pagers and cell phones. PROGRAM I Wish It So from Juno Marc Blitzstein • 1905 - 1964 My Ship from Lady in the Dark Kurt Weill • 1900 - 1950 Ira Gershwin • 1896 - 1983 Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Out There from Hunchback of Notre Dame Stephen Schwarts • b. 1948 Alan Menken • b. 1949 There Won’t Be Trumpets from Anyone Can Whistle Stephen Sondhiem • b. 1930 Ellie Wise, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Take Me to the World from Evening Primrose Stephen Sondheim The Girls of Summer from Marry Me a Little Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Glamorous Life from A Little Night Music Stephen Sondheim My New Philosophy from You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown Clark Gesner • 1938 - 2002 Ellie Wise, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Mr. Snow from Carousel Richard Rodgers • 1902 - 1979 Oscar Hammerstein II • 1895 - 1960 Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist My Party Dress from Henry and Mudge Kait Kerrigan • b. 1981 Brian Loudermilk • b. 1983 Ellie Wise, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist INTERMISSION Always a Bridesmaid from I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change Jimmy Roberts Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Music and the Mirror from A Chorus Line Joe DiPietro • b. -

Association Sunday 2009 Worship Resources

ASSOCIATION SUNDAY 2009 GROWING OUR DIVERSITY ~ WORSHIP RESOURCES ~ TABLE OF CONTENTS Checklist for Organizing Your Service..................................................... 2 Hymns in Singing the Living Tradition and Singing the Journey .............. 3 Opening Words/Call to Worship .............................................................. 4 Chalice Lighting ...................................................................................... 6 Readings .................................................................................................. 8 Prayers & Meditations ........................................................................... 17 Stories for All Ages ............................................................................... 20 Books for Stories for All Ages ............................................................... 23 Sermons ................................................................................................. 25 Words for the Offering ........................................................................... 39 Closing Words/Benedictions .................................................................. 41 Original Music by UU Composers ......................................................... 43 Links to Other Resources ....................................................................... 58 CHECKLIST FOR ORGANIZING YOUR SERVICE □ Put up the Association Sunday Posters. □ Consider doing a pulpit exchange with neighboring congregations. □ Organize the service to include lay participation. -

Lost Generation.” Two Recent Del Sol Quartet Recordings Focus on Their Little-Known Chamber Music

American Masterpieces Chamber Music Americans in Paris Like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, composers Marc Blitzstein and George Antheil were a part of the 1920s “Lost Generation.” Two recent Del Sol Quartet recordings focus on their little-known chamber music. by James M. Keller “ ou are all a lost generation,” Generation” conveyed the idea that these Gertrude Stein remarked to literary Americans abroad were left to chart Y Ernest Hemingway, who then their own paths without the compasses of turned around and used that sentence as the preceding generation, since the values an epigraph to close his 1926 novel The and expectations that had shaped their Sun Also Rises. upbringings—the rules that governed Later, in his posthumously published their lives—had changed fundamentally memoir, A Moveable Feast, Hemingway through the Great War’s horror. elaborated that Stein had not invented the We are less likely to find the term Lost locution “Lost Generation” but rather merely Generation applied to the American expa- adopted it after a garage proprietor had triate composers of that decade. In fact, used the words to scold an employee who young composers were also very likely to showed insufficient enthusiasm in repairing flee the United States for Europe during the ignition in her Model-T Ford. Not the 1920s and early ’30s, to the extent that withstanding its grease-stained origins, one-way tickets on transatlantic steamers the phrase lingered in the language as a seem to feature in the biographies of most descriptor for the brigade of American art- American composers who came of age at ists who spent time in Europe during the that moment.