Book: World Religions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Butcher, W. Scott

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project WILLIAM SCOTT BUTCHER Interviewed by: David Reuther Initial interview date: December 23, 2010 Copyright 2015 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Dayton, Ohio, December 12, 1942 Stamp collecting and reading Inspiring high school teacher Cincinnati World Affairs Council BA in Government-Foreign Affairs Oxford, Ohio, Miami University 1960–1964 Participated in student government Modest awareness of Vietnam Beginning of civil rights awareness MA in International Affairs John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies 1964–1966 Entered the Foreign Service May 1965 Took the written exam Cincinnati, September 1963 Took the oral examination Columbus, November 1963 Took leave of absence to finish Johns Hopkins program Entered 73rd A-100 Class June 1966 Rangoon, Burma, Country—Rotational Officer 1967-1969 Burmese language training Traveling to Burma, being introduced to Asian sights and sounds Duties as General Services Officer Duties as Consular Officer Burmese anti-Indian immigration policies Anti-Chinese riots Ambassador Henry Byroade Comment on condition of embassy building Staff recreation Benefits of a small embassy 1 Major Japanese presence Comparing ambassadors Byroade and Hummel Dhaka, Pakistan—Political Officer 1969-1971 Traveling to Consulate General Dhaka Political duties and mission staff Comment on condition of embassy building USG focus was humanitarian and economic development Official and unofficial travels and colleagues November -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Social Entrepreneurship – Creating Value for the Society Dr

Prabadevi M. N., International Journal of Advance Research, Ideas and Innovations in Technology. ISSN: 2454-132X Impact factor: 4.295 (Volume3, Issue2) Available online at www.ijariit.com Social Entrepreneurship – Creating Value for the Society Dr. M. N. Prabadevi SRM University [email protected] Abstract: Social entrepreneurship is the use of the techniques by start-up companies and other entrepreneurs to develop, fund and implement solutions to social, cultural, or environmental issues. This concept may be applied to a variety of organizations with different sizes, aims, and beliefs. Social Entrepreneurship is the attempt to draw upon business techniques to find solutions to social problems. Conventional entrepreneurs typically measure performance in profit and return, but social entrepreneurs also take into account a positive return to society. Social entrepreneurship typically attempts to further broad social, cultural, and environmental goals often associated with the voluntary sector. At times, profit also may be a consideration for certain companies or other social enterprises. Keywords: Social Entrepreneurship, Values, Society. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Defining social entrepreneurship Social entrepreneurship refers to the practice of combining innovation, resourcefulness, and opportunity to address critical social and environmental challenges. Social entrepreneurs focus on transforming systems and practices that are the root causes of poverty, marginalization, environmental deterioration and accompanying the loss of human dignity. In so doing, they may set up for-profit or not-for-profit organizations, and in either case, their primary objective is to create sustainable systems change. The key concepts of social entrepreneurship are innovation, market orientation and systems change. 1.2 Who are Social Entrepreneurs? A social entrepreneur is a society’s change agent: pioneer of innovations that benefit humanity Social entrepreneurs are drivers of change. -

Jain Reality Or Existence - by Pravin K

Jain Reality or Existence - By Pravin K. Shah Structural View of the Universe Jain Philosophy does not give credence to the theory that God is a creator, survivor, or destroyer of the universe. On the contrary, it asserts that the universe has always existed and will always exist in exact adherence to the laws of the cosmos. There is nothing but infinity both in the past and in the future. The world of reality or universe consists of two classes of objects: · Living beings - conscious, soul, chetan, or jiva · Non-living objects - unconscious, achetan, or ajiva Non-living objects are further classified into five categories; Matter (Pudgal), Space (Akas), Medium of motion (Dharmastikay), Medium of rest (Adharmastikay), Time (Kal or Samay). The five non-living entities together with the living being, totaling six are aspects of reality in Jainism. They are known as six universal entities, or substances, or realities. These six entities of the universe are eternal but continuously undergo countless changes. During the changes, nothing is lost or destroyed. Everything is recycled into another form. Concept of Reality A reality or an entity is defined to have an existence, which is known as Sat or truth. Each entity continuously undergoes countless changes. During this process the old form (size, shape, etc.) of an entity is destroyed, the new form is originated. The form of a substance is called Paryaya. In the midst of modification of a substance, its certain qualities remain unchanged (permanence). The unchanged qualities of a substance are collectively known as Dravya. Hence, each entity (substance) in the universe has three aspects: · Origination - Utpada · Destruction - Vyaya · Permanence - Dhruvya Both Dravya (substance) and Paryaya (mode or form) are inseparable from an entity. -

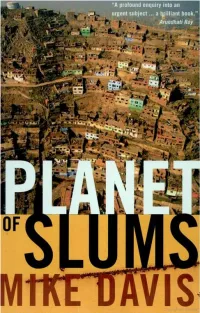

Mike Davis, Planet of Slums

- Planet of Slums • MIKE DAVIS VERSO London • New York formy dar/in) Raisin First published by Verso 2006 © Mike Davis 2006 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 357910 864 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F OEG USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014 -4606 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN 1-84467-022-8 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset in Garamond by Andrea Stimpson Printed in the USA Slum, semi-slum, and superslum ... to this has come the evolution of cities. Patrick Geddes1 1 Quoted in Lev.isMumford, The City inHistory: Its Onj,ins,Its Transf ormations, and Its Prospects, New Yo rk 1961, p. 464. Contents 1. The Urban Climacteric 1 2. The Prevalence of Slums 20 3. The Treason of the State 50 4. Illusions of Self-Help 70 5. Haussmann in the Tropics 95 6. Slum Ecology 121 .7. SAPing the Third World 151 ·8. A Surplus Humanity? 174 Epilogue: Down Vietnam Street 199 Acknowledgments 207 Index 209 1 The U rhan Climacteric We live in the age of the city. The city is everything to us - it consumes us, and for that reason we glorify it. Onookome Okomel Sometime in the next year or two, a woman will give birth in the Lagos slum of Ajegunle, a young man will flee his viJlage in west Java for the bright lights of Jakarta, or a farmer will move his impoverished family into one of Lima's innumerable pueblosjovenes . -

Plan for Irrc in G-15 (Islamabad) Ahkmt-E-Guard Initiative

INTEGRATED RESOURCE RECOVERY CENTRE G/15 ISLAMABAD Recycining center Dhaka Bangladesh Presented By Dr. Akhtar Hameed Khan Memorial Trust PLAN FOR IRRC IN G-15 (ISLAMABAD) AHKMT-E-GUARD INITIATIVE JKCHS Plan for IRRC Private Initiative 1.5 Kanal land by JKCHS Total 4600 plots 3-5 ton capacity IRRC 2200 HH are residing now UN-Habitat and UNESCAP Secondary collection system provided financial support was not available and waste concern and CCD provided technical support for AHKMT the IRRC Primary collection service is providing to almost 1500 hh through mutual agreement Primary collection will be extended gradually within 5 years PARTNERSHIP ARRANGEMENTS SITUATION IN ISLAMABAD As per survey in 2014 total population is 1.67 million and waste amount was 800 tons p/day Landfill site is still required Secondary collection and waste transportation requires huge funds Recyclables and organic material is not being utilized Mostly Housing societies of Zone II and Zone V have not proper waste collection and disposal system Present Situation Mixed Waste Waste Bins Demountable Transfer Containers Stations Landfill PROBLEMS Water Pollution Spread of Disease Vectors Green House Gas Emission Odor Pollution More Land Required for Landfill What is Integrated Resource Recovery Center (IRRC)? IRRC is a facility where significant portion (80-90%) of waste can be composted/recycled and processed in a cost effective way near the source of generation in a decentralized manner. IRRC is based on 3 R Principle. Capacity of IRRC varies from 2 to -

Persian Royal Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY PERSIAN ROYAL ANCESTRY Achaemenid Dynasty from Greek mythical Perses, (705-550 BC) یشنماخه یهاشنهاش (Achaemenid Empire, (550-329 BC نايناساس (Sassanid Empire (224-c. 670 INTRODUCTION Persia, of which a large part was called Iran since 1935, has a well recorded history of our early royal ancestry. Two eras covered are here in two parts; the Achaemenid and Sassanian Empires, the first and last of the Pre-Islamic Persian dynasties. This ancestry begins with a connection of the Persian kings to the Greek mythology according to Plato. I have included these kind of connections between myth and history, the reader may decide if and where such a connection really takes place. Plato 428/427 BC – 348/347 BC), was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. King or Shah Cyrus the Great established the first dynasty of Persia about 550 BC. A special list, “Byzantine Emperors” is inserted (at page 27) after the first part showing the lineage from early Egyptian rulers to Cyrus the Great and to the last king of that dynasty, Artaxerxes II, whose daughter Rodogune became a Queen of Armenia. Their descendants tie into our lineage listed in my books about our lineage from our Byzantine, Russia and Poland. The second begins with King Ardashir I, the 59th great grandfather, reigned during 226-241 and ens with the last one, King Yazdagird III, the 43rd great grandfather, reigned during 632 – 651. He married Maria, a Byzantine Princess, which ties into our Byzantine Ancestry. -

Europe: 400 to 301 B.C. 9/13/11 3:16 PM

Europe: 400 to 301 B.C. 9/13/11 3:16 PM Connexions You are here: Home » Content » Europe: 400 to 301 B.C. Europe: 400 to 301 B.C. Module by: Jack E. Maxfield. Europe Back to Europe: 500 to 401 B.C. (http://cnx.org/content/m17852/latest/) SOUTHERN EUROPE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN ISLANDS In the last third of this century, all these islands were conquered by the men of Alexander the Great, but his control was short-lived. By 323 B.C. Rhodes was independent again and Cyprus belonged to Egypt until Demetrius Poliocertes, aspirant to the throne of Macedon, took Cyprus again. Then in 307 he besieged Rhodes, using 30,000 men to build siege towers and engines, but all of this failed. (Ref. 38 (http://cnx.org/content/m17805/latest/#threeeight) , 222 (http://cnx.org/content/m17805/latest/#twotwotwo) ) GREECE Throughout the peninsula there was endless conflict between the slaves and the ruined proletarian masses who demanded that the state support them. Up until about 378 B.C. the police force of Athens consisted of about 300 state-owned Scythian slaves. At the beginning of the century Sparta, having won the Peloponnesian War with the help of subsidies from Persia, dominated southern Greece; then, by forming an "Arcadian League", Thebes took over control from about 370 to 360 B.C.; then Athens, with growing special- ization of professional soldiers and generals, professional orators and financial experts be- came supreme for awhile. But in the last part of the century the unity which the Greeks could not find among themselves was forced on them by Philip of Macedon. -

The Jaina Response to Samavaya

Chapter-10 The Jaina Response to Samavaya. I The Jaina outlook on ontology and its philosophy of knowledge can be comprehended under realism, and in this regard, it shares a lot of views and ideas with Nyaya-Vai5e$ika and realist schools. A schematic representation of Jainism may be given below in order to put its perspective amongst other philosophical views. Knowledge I Realism Idealism Direct Presentation Represent tion I Nyaya Mlmamsa Jaina Samkhya Sautantrika Vedanta Yogacara Jainism is distinguished by having its sources in the Bhagavati, and Agama literature. It is classified as a non-Vedic or heterodox school of thought, but nonetheless Jainism is a mok?asastra, the science of salvation. The path for spiritual progress, aiming at the final goal of liberation is the central tone of the Agamas. The Jainas arrange the knowledge of the world under two pairs of contrasted alternatives, jiva and ajiva. These are complementary aspects of reality, each of which suggests the other by a dialectical necessity and combines with the other into one more complex conception. These two contrasted alternatives are but two conditions of thought: all thinking implies a subject which thinks, the cogitative principle or soul. But as all thinking is thinking of something, it means that it requires a material on which the thought activity is exercised, it implies an object which is discriminated and understood by thought. The Jainas speak of knowledge in five different forms: (a) Mati or that form of knowledge by which a jiva cognizes an object through the operation of the sense-organs, all hindrances to the formation of such knowledge being removed. -

Jain Philosophy and Practice I 1

PANCHA PARAMESTHI Chapter 01 - Pancha Paramesthi Namo Arihantänam: I bow down to Arihanta, Namo Siddhänam: I bow down to Siddha, Namo Äyariyänam: I bow down to Ächärya, Namo Uvajjhäyänam: I bow down to Upädhyäy, Namo Loe Savva-Sähunam: I bow down to Sädhu and Sädhvi. Eso Pancha Namokkäro: These five fold reverence (bowings downs), Savva-Pävappanäsano: Destroy all the sins, Manglänancha Savvesim: Amongst all that is auspicious, Padhamam Havai Mangalam: This Navakär Mantra is the foremost. The Navakär Mantra is the most important mantra in Jainism and can be recited at any time. While reciting the Navakär Mantra, we bow down to Arihanta (souls who have reached the state of non-attachment towards worldly matters), Siddhas (liberated souls), Ächäryas (heads of Sädhus and Sädhvis), Upädhyäys (those who teach scriptures and Jain principles to the followers), and all (Sädhus and Sädhvis (monks and nuns, who have voluntarily given up social, economical and family relationships). Together, they are called Pancha Paramesthi (The five supreme spiritual people). In this Mantra we worship their virtues rather than worshipping any one particular entity; therefore, the Mantra is not named after Lord Mahävir, Lord Pärshva- Näth or Ädi-Näth, etc. When we recite Navakär Mantra, it also reminds us that, we need to be like them. This mantra is also called Namaskär or Namokär Mantra because in this Mantra we offer Namaskär (bowing down) to these five supreme group beings. Recitation of the Navakär Mantra creates positive vibrations around us, and repels negative ones. The Navakär Mantra contains the foremost message of Jainism. The message is very clear. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

ANTONIJE SHKOKLJEV SLAVE NIKOLOVSKI - KATIN PREHISTORY CENTRAL BALKANS CRADLE OF AEGEAN CULTURE Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69