The Italian System of Marine Protected Areas Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feral Breeds in Italy

Feral breeds in Italy Daniele Bigi RARE Association University of Bologna 6 feral populations in Italy • Giara Horse • Asinara Donkeys • Asinara Horses • Asinara Goat SARDINIA • Tavolara Goat • Caprera Goat • Molara Goat • Montecristo Goat TUSCANY • Tremiti Goat PUGLIA ? Feral and wild populations on the Asinara Island • Donkeys: – White donkey (Asino dell’Asinara) (150 amimals) – Grey donkey (250 animals) • Goats > 1000 (6000 have been already removed from the Island). • Horses 100 • Mouflons (number unknown) Asinara Island – The Island is 52 km 2 in area. – The name is Italian for "donkey-inhabited“. – The island is located off the north-western tip of Sardinia. – The Island is mountainous in geography with steep, rocky coast. Trees are sparse and low scrub is the predominant vegetation. – It’s part of the national parks system of Italy, in 2002 the island was converted to a wildlife and marine preserve. – In 1885 the island became a Lazaretto and an agricultural penal colony (till 1998). About 100 families of Sardinian farmers and Genoese fishermen who lived on Asinara were obliged to move to Sardinia, where they founded the village of Stintino. Asino dell’Asinara (Asinara Donkey) Origins: - Uncertain but oral records report the presence of white donkeys on the island since the end of XIX century. - the appearance of the white coat in more recent times is probably due to a random mutation that spread to all the population. Morphology: it is small and the size is similar to the Sardinian donkey; the most important difference is the white coat, that probably belongs to a form of incomplete albinism . -

1 Lgbtgaily Tours & Excursions

LGBT 1 OurOur Tour. YourLGBT Pride. Philosophy We have designed a new product line for a desire to be part of the colorful battle for human LGBT publicum, offering more than a simple pride with friends from all over the world, Iwe travel! If you are looking for a special itinerary have the perfect solution for you. in Italy discovering beautiful landscapes and uncountable art and cultural wonders, or if you We want to help in creating a rainbow world. and now choose your LGBT experience... Follow us on: www.GailyTour.com @GailyTour @gailytour Largo C. Battisti, 26 | 39044 - Egna (BZ) - ITALY Tel. (+39) 0471 806600 - Fax (+39) 0471 806700 VAT NUMBER IT 01652670215 Our History & Mission Established in 1997 and privately owned, Last addition to the company’s umbrella is the providing competitive travel services. Ignas Tour has been making a difference to office in Slovakia opened in 2014, consolidating Trust, reliability, financial stability, passion and our client’s group traveling experiences for two Ignas Tour's presence in the Eastern European attention to details are key aspects Ignas Tour decades. market and expanding and diversifying even is known for. In 1999 opening of a sister company in more the product line. The company prides itself on a long-term vision Hungary, adding a new destination to the Ignas Tour maintains an uncompromising and strategy and keeps in sync with the latest company’s portfolio. Since 2001 IGNAS TOUR commitment to offer the highest standards market trends in order to develop new products is also part of TUI Travel plc. -

Tonnare in Italy: Science, History, and Culture of Sardinian Tuna Fishing 1

Tonnare in Italy: Science, History, and Culture of Sardinian Tuna Fishing 1 Katherine Emery The Mediterranean Sea and, in particular, the cristallina waters of Sardinia are confronting a paradox of marine preservation. On the one hand, Italian coastal resources are prized nationally and internationally for their natural beauty as well as economic and recreational uses. On the other hand, deep-seated Italian cultural values and traditions, such as the desire for high-quality fresh fish in local cuisines and the continuity of ancient fishing communities, as well as the demands of tourist and real-estate industries, are contributing to the destruction of marine ecosystems. The synthesis presented here offers a unique perspective combining historical, scientific, and cultural factors important to one Sardinian tonnara in the context of the larger global debate about Atlantic bluefin tuna conservation. This article is divided into four main sections, commencing with contextual background about the Mediterranean Sea and the culture, history, and economics of fish and fishing. Second, it explores as a case study Sardinian fishing culture and its tonnare , including their history, organization, customs, regulations, and traditional fishing method. Third, relevant science pertaining to these fisheries’ issues is reviewed. Lastly, the article considers the future of Italian tonnare and marine conservation options. Fish and fishing in the Mediterranean and Italy The word ‘Mediterranean’ stems from the Latin words medius [middle] and terra [land, earth]: middle of the earth. 2 Ancient Romans referred to it as “ Mare nostrum ” or “our sea”: “the territory of or under the control of the European Mediterranean countries, especially Italy.” 3 Today, the Mediterranean Sea is still an important mutually used resource integral to littoral and inland states’ cultures and trade. -

Measures to Mitigate Adverse Impacts of Fisheries Targeting Large Pelagics

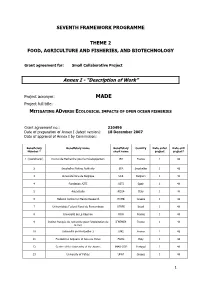

SEVENTH FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME THEME 2 FOOD, AGRICULTURE AND FISHERIES, AND BIOTECHNOLOGY Grant agreement for: Small Collaborative Project Annex I - “Description of Work” Project acronym: MADE Project full title: MITIGATING ADVERSE ECOLOGICAL IMPACTS OF OPEN OCEAN FISHERIES Grant agreement no.: 210496 Date of preparation of Annex I (latest version): 18 December 2007 Date of approval of Annex I by Commission: Beneficiary Beneficiary name Beneficiary Country Date enter Date exit Number * short name project project* 1 (Coordinator) Institut de Recherche pour le Développement IRD France 1 48 2 Seychelles Fishing Authority SFA Seychelles 1 48 3 Université libre de Belgique ULB Belgium 1 48 4 Fundacion AZTI AZTI Spain 1 48 5 Aquastudio AQUA Italy 1 48 6 Hellenic Centre for Marine Research HCMR Greece 1 48 7 Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco UFRPE Brazil 1 48 8 Université de La Réunion RUN France 1 48 9 Institut français de recherche pour l’exploitation de IFREMER France 1 48 la mer 10 Université de Montpellier 2 UM2 France 1 48 11 Fondazione Acquario di Genova Onlus FADG Italy 1 48 12 Centre of the University of the Azores IMAR-DOP Portugal 1 48 13 University of Patras UPAT Greece 1 48 1 Table of contents Part A........................................................................................................................3 A1 Overall budget breakdown for the project .....................................................4 A2 Project summary.........................................................................................5 A3 -

S Italy Is a Contracting Party to All of the International Conventions a Threat to Some Wetland Ibas (Figure 3)

Important Bird Areas in Europe – Italy ■ ITALY FABIO CASALE, UMBERTO GALLO-ORSI AND VINCENZO RIZZI Gargano National Park (IBA 129), a mountainous promontory along the Adriatic coast important for breeding raptors and some open- country species. (PHOTO: ALBERTO NARDI/NHPA) GENERAL INTRODUCTION abandonment in marginal areas in recent years (ISTAT 1991). In the lowlands, agriculture is very intensive and devoted mainly to Italy covers a land area of 301,302 km² (including the large islands arable monoculture (maize, wheat and rice being the three major of Sicily and Sardinia), and in 1991 had a population of 56.7 million, crops), while in the hills and mountains traditional, and less resulting in an average density of c.188 persons per km² (ISTAT intensive agriculture is still practised although land abandonment 1991). Plains cover 23% of the country and are mainly concentrated is spreading. in the north (Po valley), along the coasts, and in the Puglia region, A total of 192 Important Bird Areas (IBAs) are listed in the while mountains and hilly areas cover 35% and 41% of the land present inventory (Table 1, Map 1), covering a total area of respectively. 46,270 km², equivalent to c.15% of the national land area. This The climate varies considerably with latitude. In the south it is compares with 140 IBAs identified in Italy in the previous pan- warm temperate, with almost no rain in summer, but the north is European IBA inventory (Grimmett and Jones 1989; LIPU 1992), cool temperate, often experiencing snow and freezing temperatures covering some 35,100 km². -

Pier Virgilio Arrigoni the Discovery of the Sardinian Flora

Pier Virgilio Arrigoni The discovery of the Sardinian Flora (XVIII-XIX Centuries) Abstract Arrigoni, P. V.: The discovery of the Sardinian Flora (XVIII-XIX Centuries). — Bocconea 19: 7-31. 2006. — ISSN 1120-4060. The history of the floristic exploration of Sardinia mainly centres round the works of G.G. Moris, who in the first half of the XIX century described most of the floristic patrimony of the island. But it is important to know the steps he took in his census, the areas he explored, his publications, motivations and conditions under which he wrote the "Stirpium sardoarum elenchus" and the three volumes of "Flora sardoa", a work moreover which he left incomplete. Merit is due to Moris for bringing the attention of many collectors, florists and taxonomists to the Flora of the Island, individuals who in his foot-steps helped to complete and update the floristic inventory of the island. Research into the history of our knowledge of the Sardinian Flora relies heavily on the analysis of botanical publications, but many other sources (non- botanical texts, chronicles of the period, correspondence) also furnish important information. Finally, the names, dates and collection localities indicated on the specimens preserved in the most important herbaria were fundamental in reconstructing the itineraries of the sites Moris visited. All these sources allowed us to clarify several aspects of the expeditions, floristic col- lections and results of his studies. The "discovery phase" of Sardinian Flora can be considered over by the end of the XIX century with the publication of the "Compendium" by Barbey (1884-1885) and "Flora d'Italia" by Fiori & Paoletti (1896-1908). -

NOVEL UNIVERSAL PRIMERS for METABARCODING Edna SURVEYS of MARINE MAMMALS and OTHER MARINE VERTEBRATES

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/759746; this version posted September 5, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Elena Valsecchi1, Jonas Bylemans2, Simon J. Goodman3, Roberto Lombardi1, Ian Carr4, Laura Castellano5, Andrea Galimberti6, Paolo Galli1,7 NOVEL UNIVERSAL PRIMERS FOR METABARCODING eDNA SURVEYS OF MARINE MAMMALS AND OTHER MARINE VERTEBRATES 1 Department of Environmental and Earth Sciences, University of Milano-Bicocca, Piazza della Scienza 1, 20126 Milan, Italy 2 Fondazione Edmund Mach, Via E. Mach 1, 38010 S. Michele all'Adige (TN), Italy 3 School of Biology, University of Leeds, Woodhouse Lane, Leeds LS2 9JT, United Kingdom 4 Leeds Institute of Molecular Medicine, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds LS9 7TF, United Kingdom 5 Acquario di Genova, Costa Edutainment SPA, Area Porto Antico, Ponte Spinola, 16128 Genoa, Italy 6 Department of Biotechnology and Biosciences, University of Milano-Bicocca, Piazza della Scienza 2, 20126 Milan, Italy 7 MaRHE Center, Magoodhoo Island, Faafu Atoll, Republic of Maldives Corresponding author: [email protected] ORCID ID 0000.0003.3869.6413 Key words: 12S, 16S, cetaceans, pinnipeds, fish, sea turtles Running title: Marine Vertebrate Universal Markers for eDNA Metabarcoding bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/759746; this version posted September 5, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Fulvio Maffucci for providing marine turtles DNAa samples. Giudo Gnone of the Aquarium of Genoa for allowing and supporting collection of controlled environmental eDNA samples. -

Rapporto Isole Sostenibili 2020

Edizione 2020 ENERGIA, ACQUA, MOBILITÀ, ECONOMIA CIRCOLARE, TURISMO SOSTENIBILE. Le sfide per le isole minori e le buone pratiche dal mondo. CNR-IIA Edizione 2020 ENERGIA, ACQUA, MOBILITÀ, ECONOMIA CIRCOLARE, TURISMO SOSTENIBILE. Le sfide per le isole minori e le buone pratiche dal mondo. OSSERVATORIO ISOLE SOSTENIBILI - RAPPORTO 2020 Indice Premessa .................................................................................................................................................................... pg 7 Le................................................................ Sfide Per Le Isole Minori Italiane .................................................................................................... pg 9 La Sostenibilità.......................................................... Nelle Isole Minori Italiane .......................................................................................................... pg 15 Energia.................................................................................................................................................................... pg 15 Acqua.................................................................................................................................................................... pg 19 Rifiuti.................................................................................................................................................................... pg 26 Mobilità................................................................................................................................................................... -

UNIONE TESI Enrico Paliaga Consegna

University of Cagliari DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN SCIENZE DELLA TERRA Ciclo XXVIII UPPER SLOPE GEOMORPHOLOGY OF SARDINIAN SOUTHERN CONTINENTAL MARGIN, APPLICATIONS TO HABITAT MAPPING SUPPORTING MARINE STRATEGY Scientific disciplinary field: GEO/04 Presented by: Dott. Enrico Maria Paliaga PhD coordinator: Prof. Marcello Franceschelli Tutor: Prof. Paolo Emanuele Orrù academic year 2014 - 2015 Enrico M. Paliaga gratefully acknowledges Sardinia Regional Government for the financial support of his PhD scholarship (P.O.R. Sardegna F.S.E. Operational Programme of the Autonomous Region of Sardinia, European Social Fund 2007–2013 —Axis IV Human Resources, Objective l.3, Line of Activity l.3.1.) 2 3 Sommario GEOGRAPHIC LOCALIZATION .................................................................... 7 REGIONAL GEOLOGICAL SETTING ............................................................ 9 2.1 PALEOZOIC METHAMORFIC BASEMENT ..................................... 12 2.2MESOZOIC AND PALAEOGENE COVERS ...................................... 18 2.3 OLIGO-MIOCENE TECTONICS ......................................................... 18 2.3.1 Sardinian Rift Setting ....................................................................... 21 2.4 Upper Miocene – Pliocene ...................................................................... 23 2.5 Pleistocene .............................................................................................. 24 2.6 Holocene ................................................................................................ -

In Compliance with Paragraph 20 of the Action Plan, a Directory of Specialists, Laboratories and Organisations Concerned By

EP United Nations Environment Programme UNEP(DEC)/MED WG.268/6 25 Mai 2005 ANGLAIS ORIGINAL: FRANCAIS MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN Seventh Meeting of the Focal Points for SPAs Seville, 31 May to 3rd of June 2005 EVALUATION REPORT ON IMPLEMENTING THE ACTION PLAN FOR THE CONSERVATION OF MARINE VEGETATION IN THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA UNEP RAC/SPA - Tunis, 2005 UNEP(DEC)/MED WG.268/6 Page 1 EVALUATION REPORT ON IMPLEMENTING THE ACTION PLAN FOR THE CONSERVATION OF MARINE VEGETATION IN THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA Introduction In the context of the Mediterranean Action Plan (MAP), the Contracting Parties to the Barcelona Convention adopted at their Eleventh Ordinary Meeting held in Malta in October 1999 an ‘Action Plan for the conservation of marine vegetation in the Mediterranean Sea’ with an accompanying implementation schedule that ended in 2006. The programme of this Action Plan was as follows: it contained 12 actions ordered in response to both the aims articulated in Article 7, and the priorities stated in Article 8. Programme and schedule for implementing the Action Plan for the conservation of marine vegetation in the Mediterranean Sea Action Deadline 1. Ratifying the new SPA Protocol As quickly as possible First symposium before 2. Mediterranean symposium November 2000, then every four years 3. Guidelines for impact studies October 2000 4. First version of the Mediterranean data bank October 2000 5. First issue of the Directory of specialists, laboratories and organisations concerned by October 2000 marine vegetation in the Mediterranean 6. Launching procedures for the legal protection of Some time in 2001 species at national level 7. -

Capraia (?) S.Pietro Giglio

Valle d'Aosta Piemonte Lombardia Trentino Alto-Adige Veneto Friuli Venezia-Giulia Liguria Emilia Romagna Toscana Umbria Marche Lazio Abruzzo Molise Campania Basilicata Puglia Calabria Sicilia Sardegna Elba Ponziane Eolie Egadi Tremiti Pantelleria Corsica Vallese (CH) Grigioni (CH) Ticino (CH) Malta Istria Slovenia Croazia Alpi Marittime francesi isole minori Sialis fuliginosa Pictet Sialis lutaria (Linnaeus) ? Sialis morio Klingstedt Sialis nigripes Pictet Phaeostigma galloitalicum (A. & A.) ? Phaeostigma italogallicum (A. & A.) Phaeostigma notatum (F.) ? ? ? ? Phaeostigma grandii (Principi) Phaeostigma major (Burmeister) ? Dichrostigma flavipes (Stein) Tjederiraphidia santuzza A., A. & R. Subilla confinis (Stephens) ? ? Subilla principiae Pantaleoni, A., Cao & A. Ornatoraphidia flavilabris (Albarda) ? Turcoraphidia amara (A. & A.) Xanthostigma xanthostigma Schum.? ? ? Xanthostigma corsicum (Hagen) ? Giglio Xanthostigma aloysianum (Costa)? Raphidia oph. ophiopsis Linnaeus ? ? Raphidia mediterranea A., A. & R. ? ? Raphidia ulrikae Aspöck Raphidia ligurica Albarda ? Atlantoraphidia maculicollis Steph. ? Italoraphidia solariana (Navás) Puncha ratzeburgi (Brauer) Calabroraphidia renate R., A. H. & A. U. Venustoraphidia nigricollis Albarda? ? ? Fibla maclachlani (Albarda) ? S.Pietro (?) Parainocellia braueri (Albarda) Parainocellia bicolor (Costa) Inocellia crassicornis (Schummel) Aleuropteryx loewii Klapalek Aleuropteryx juniperi Ohm Aleuropteryx umbrata Zeleny Helicoconis lutea (Wallengren) ? ? Helicoconis hirtinervis Tjeder ? Helicoconis -

Mediterranean Marine Science

Mediterranean Marine Science Vol. 0 MEDLEM database, a data collection on large Elasmobranchs in the Mediterranean and Black seas MANCUSI CECILIA Environmental Protection Agency (ARPAT) BAINO ROMANO Environmental Protection Agency (ARPAT) FORTUNA CATERINA Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA) DE SOLA LUIS GIL IEO MOREY GABRIEL Balearic Islands Government BRADAI MOHAMED INSTM NEJMEDDINE KALLIANOTIS ARGYRIOS N.AG.RE.F SOLDO ALEN University of Split HEMIDA FARID USTHB SAAD ADIB ALI Tishreen University DIMECH MARK Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) PERISTERAKI PANAGIOTAHellenic Center for Marine Research BARICHE MICHEL American University of Beirut CLÒ SIMONA Medsharks DE SABATA ELEONORA Medsharks CASTELLANO LAURA Aquarium of Genoa GARIBALDI FULVIO University of Genoa LANTERI LUCA University of Genoa TINTI FAUSTO University of Bologna PAIS ANTONIO University of Sassari SPERONE EMILIO University of Calabria MICARELLI PRIMO Aquarium of Massa Marittima POISSON FRANCOIS MARBEC, Univ. Montpellier, CNRS, Ifremer, IRD SION LETIZIA University of Bari CARLUCCI ROBERTO University of Bari CEBRIAN-MENCHERO RAC-SPA DANIEL SÉRET BERNARD Ichtyo Consult FERRETTI FRANCESCO Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford University EL-FAR ALAA National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries (NIOF) http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 27/05/2020 16:13:47 | SAYGU ISMET SHAKMAN ESMAIL University of Tripoli BARTOLI ALEX SUBMON – Marine Environmental Services GUALLART JAVIER University of Valencia