Caught Between the EU's and Russia's Conditionalities?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ture in the Czech Republic

Brno 15 November 2020 Establishment of the Embassy of Independent Belarusian Cul- ture in the Czech Republic The Centre for Experimental Theatre in Brno (CED), which includes the Husa na Provazku Thea- tre, HaDivadlo and the Teren Platform, is setting up an Embassy of Independent Belarusian Culture in the Czech Republic in Brno. The opening of the embassy is symbolically directed to November 17, which is a national holiday in the Czech Republic and a Day of the Struggle for Freedom and Democracy. The Czechs have experience with both the totalitarian regime and civic protests against un- democratic behaviour and their subsequent repression. Therefore, in recent months, the Centre for Experimental Theatre has been closely following events in Belarus, where people have been fighting for fair elections, freedom and democracy for four months now, despite widespread ar- rests, imprisonment, harsh repression and intimidation. On Tuesday, November 17, 2020, we commemorate the anniversary of the Velvet Revolution and the victory of freedom and democracy in our country. The Centre for Experimental Theatre intends to follow the legacy of Vaclav Havel on this important day, and this time it is going to use the ethos of this day to commemorate what is happening in Belarus these days. „We contemplated what form would be the best to choose and agreed that it is not very useful to organize a one-day debate or similar event, but that most of all it is necessary to continu- ously and consistently inform the general public in the longer term about what is happening in Belarus these days. -

Protecting Democracy During COVID-19 in Europe and Eurasia and the Democratic Awakening in Belarus Testimony by Douglas Rutzen

Protecting Democracy During COVID-19 in Europe and Eurasia and the Democratic Awakening in Belarus Testimony by Douglas Rutzen President and CEO International Center for Not-for-Profit Law House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, Energy, and the Environment September 10, 2020 In April, Alexander Lukashenko declared that no one in Belarus would die of coronavirus.1 To allay concerns, he advised Belarussians to drink vodka, go to saunas, and drive tractors.2 In Hungary, Orban took a different approach. He admitted there was COVID-19, and he used this as an excuse to construct a legal framework allowing him to rule by decree.3 Meanwhile, China is using the pandemic to project its political influence. When a plane carrying medical aid landed in Belgrade, the Serbian President greeted the plane and kissed the Chinese flag. Billboards soon appeared in Belgrade, with Xi Jinping’s photo and the words “Thanks, Brother Xi” written in Serbian and Chinese.4 COVID-19 is not the root cause of Lukashenko’s deceit, Orban’s power grab, or China’s projection of political influence. But the pandemic exposed – and in some countries, exacerbated – underlying challenges to democracy. In my testimony, I will summarize pre-existing challenges to democracy. Second, I will examine how COVID-19 combined with pre-existing conditions to accelerate democratic decline in Europe and Eurasia. Third, I will share attributes of authoritarian and democratic responses to the pandemic. I will conclude with recommendations. Pre-Existing Challenges to Democracy According to Freedom House, 2019 marked the 14th year of decline in democracy around the world.5 The “democratic depression” is particularly acute in Eurasia, where the rule of law and freedom of expression declined more than in any other region.6 Indeed, Freedom House classifies zero countries in Eurasia as “free.” ICNL specializes in the legal framework for civil society, particularly the freedoms of association, peaceful assembly, and expression. -

BELARUS // Investing in Future Generations to Seize a ‘Demographic Dividend’

Realising Children’s Rights through Social Policy in Europe and Central Asia Action Area 2 A Compendium of UNICEF’s Contributions (2014-2020) 60 BELARUS // Investing in Future Generations to Seize a ‘Demographic Dividend’ © UNICEF/UN0218148/Noorani Realising Children’s Rights through Social Policy in Europe and Central Asia 61 A Compendium of UNICEF’s Contributions (2014-2020) Belarus Issue Belarus has made great progress in achieving its SDG aged 65 and older) per working-age adults aged 15-65 years indicators related to children and adolescents early. is 0.46.127 Thus, Belarus has a relatively low dependency ratio Nevertheless, one concern requiring rapid strategic and therefore wise investments in fewer dependents now attention is the exigency of seizing the country’s could effectively enable the next generation of workers to pay ‘demographic dividend’. After a two-year recession, pension contributions and to look after a larger dependent Belarus’ economic situation improved in 2017 and child population. Together, 19% or 138,000 adolescents experience poverty decreased to 10.4% in 2018. This represented an vulnerabilities128 (i.e. substance use, conflicts with the law, improvement on recent years, although the historical low violence, mental health challenges, disability, and living without remains the 9.2% achieved in 2014.125 However, in 2019 the family care or in poverty etc.).129 If not addressed promptly, country again faced an economic slowdown. In the midterm, those vulnerabilities, especially multidimensional ones, will the World Bank (WB) projects GDP growth of around 1%, have adverse impacts on their quality and longevity of life below what is needed to raise living standards. -

Belarus - a Unique Case in the European Context?

Belarus - A Unique Case in the European Context? By Peter Kim Laustsen* Introduction Remaking of World Order2 , where he ex- Federation, Ukraine, Romania, Bosnia and pressed a more pessimistic view. It was Herzegovina, Croatia, the Former Since the end of the Cold War and the claimed that the spreading of liberal de- Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and break-up of the Soviet Union, a guiding mocracy had reached its limits and that Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) did paradigm in the discussions concerning outside its present boundaries (primarily support Huntingtons theory. political changes in Central and Eastern Western Europe) this form of government The development in the latest years has Europe has been a positive and optimis- would not be able to take root. shown progress in all but a few of the tic believe in progress towards the vic- The political development that took above mentioned states. Reading Freedom tory of a liberal democracy. This view was place in the years after the fall of the Ber- Houses surveys on the level of political clearly expressed by Francis Fukuyama in lin Wall and the birth and rebirth of the rights and civil liberties gives hope. his widely discussed book The End of successor states of the Soviet Union, Widely across Europe these rights and lib- History and the Last Man1 . The optimistic Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia did not erties have been and are still expanding view of the political changes was however however support Fukuyamas claim. On and deepening. One state does clearly sepa- challenged by Samuel P. Huntington in the contrary, the political upheaval in, for rate itself from the trends in Eastern and his book The Clash of Civilizations and the instance, Slovakia, Belarus, the Russian Central Europe: Belarus. -

Political Risks of Economic

6 СВІТОВЕ ГОСПОДАРСТВО І МІЖНАРОДНІ ЕКОНОМІЧНІ ВІДНОСИНИ Viljar Veebel 1 POLITICAL RISKS OF ECONOMIC DEPENDENCE FROM RUSSIA: THE EVIDENCE FROM UKRAINE, BELARUS, ARMENIA AND GEORGIA This study focuses on political risks coming together with economic dependence for Belarus, Armenia, Ukraine and Georgia, in case of their attempt to escape the influence of Russia. Based on the assumption that a common pattern exists in Russia’s behaviour during the conflicts in Georgia and Ukraine the economic consequences of a potential change of course towards the EU of these states are assessed. Keywords: Russia; imperialism; political risks; economic dependence; Georgia; Ukraine. Peer-reviewed, approved and placed: 31.01.2017. Вільяр Вібель ПОЛІТИЧНІ РИЗИКИ ЕКОНОМІЧНОЇ ЗАЛЕЖНОСТІ ВІД РОСІЇ: ЗА ДАНИМИ УКРАЇНИ, БІЛОРУСІ, ВІРМЕНІЇ ТА ГРУЗІЇ У статті описано політичні ризики в контексті економічної залежності Білорусі, Вірменії, України та Грузії від Росії, а також у контексті їх спроб мінімізувати вплив цієї країни. Якщо зробити припущення про існування в геополітичній поведінці Росії певних патернів (на прикладах військових конфліктів в Грузії та Україні), можна описати потенційні економічні наслідки євроорієнтації цих країн. Ключові слова: Росія; імперіалізм; політичні ризики; економічна залежність; Грузія; Україна. Рис. 5. Літ. 19. Вильяр Вибель ПОЛИТИЧЕСКИЕ РИСКИ ЭКОНОМИЧЕСКОЙ ЗАВИСИМОСТИ ОТ РОССИИ: ПО ДАННЫМ УКРАИНЫ, БЕЛАРУСИ, АРМЕНИИ И ГРУЗИИ В статье описаны политические риски в контексте экономической зависимости Беларуси, Армении, Украины и Грузии от России, а также в контексте их попыток мини - мизировать влияние данной страны. Если предположить, что в геополитическом поведе - ние России существуют некие паттерны (на примерах военных конфликтов в Грузии и Украине), можно описать потенциальные экономические последствия евроориентации данных стран. Ключевые слова: Россия; империализм; политические риски; экономическая зависимость; Грузия; Украина. -

Georgia's Vulnerability to Russian Pressure Points

MEMO POLICY GEORGIA’S VULNERABILITY TO RUSSIAN PRESSURE POINTS Sergi Kapanadze Since the Association Agreement fallout in Ukraine, it has SUMMARY Georgia is set to sign the Association Agreement become abundantly clear that Russia is prepared to fight to with the EU this month. Given the dramatic protect what it considers its sphere of influence and to block turn of events in Ukraine and the conflicts that the countries in the “common neighbourhood” from moving Georgia’s past Western integration efforts have roused, Tbilisi has good cause to worry. Russia closer to the European Union. This is certainly true of Georgia, has made its disapproval of a European path where Russia has tested a wide range of instruments over the for its small, southern neighbour clear and is last 20 years to retain influence over its former vassal. From likely to utilise whatever means it has to derail economic embargoes, the expulsion of Georgian citizens, Georgia’s European ambitions. and the occupation of Georgia’s territories, to terrorist This paper analyses the various economic, attacks and direct interference in domestic politics, Russia political, and military pressure points that has applied an array of tactics to undermine the Georgian Russia can target. Georgia has decreased its state, intensifying the pressure whenever Georgia attempted dependency on Moscow substantially since its last dramatic conflict with Moscow in 2007. to enhance its relations with the West. However, this memo argues that Russia still has the means to influence Georgia’s foreign- Russia’s leaders have repeatedly made it clear that they will policy choices by attacking strategic bilateral not accept European integration for the Eastern Partnership vulnerabilities that include wine exports, remittances, investment, winter oil supplies, (EaP) countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, domestic divisions, and the occupied regions of Moldova, and Ukraine). -

Box 3 Economic Ties Between Lithuania and Belarus

BOX 3 ECONOMIC TIES BETWEEN LITHUANIA AND BELARUS Trade in services is one of the strongest ties between Lithuania and Belarus. The largest volume of imports of services to Lithuania comes from Belarus – in 2019, it amounted to €0.68 billion (10% of total imports of services). During the same period, Lithuania exported services worth €0.72 billion to Belarus (6% of total imports of services) and, as per this indicator, the neighbouring country was surpassed only by Germany, Russia and France. As transport services account for the bulk of bilateral trade, they are most likely to be affected by the Belarusian economic problems. Some of the largest exporters in the transport sector are Lietuvos Geležinkeliai (Lithuanian Railways) and Klaipėdos Uostas (Port of Klaipėda), thus Belarus uses services of these companies to transport goods. In 2019, almost 12% of rail freight loaded in Lithuania was unloaded in Belarus, and as much as 75% of total rail freight unloaded in Lithuania was loaded in Belarus. In the cargo turnover of the Port of Klaipėda, cargo from Belarus comprises up to a third of its total cargo. Belarus is also important to Lithuania in terms of the tourism sector. Most of the tourists that came to Lithuania in 2019 with an overnight stay were from Belarus. Belarusians are keen on Lithuania not only for tourism, but also for shopping – their spending share here is some of the largest. Last year, visitors from Belarus spent more than €130 million in Lithuania, which comprises 14% of its total tourist spending. As regards trade in goods, Lithuania for Belarus is a transit country through which machinery, equipment and vehicles are transferred from the West. -

PROGRAM 10 Transition and Developed Countries Performance

PROGRAM 10 Transition and Developed Countries 1 Performance Data On track Not on track N/A 2020 Not assessable Discontinued Performance Indicators Baselines Targets Performance Data PIE I.2 Tailored and balanced IP legislative, regulatory and policy frameworks No. of transition countries with 7 countries in the 28 countries 5 baseline countries further updated national updated national laws and biennium laws and regulations: Belarus, Kazakhstan, regulations Poland, Serbia, Ukraine (28 transition countries cumulative) No. of ratifications by transition 535 ratifications by 29 8 additional 4 ratifications: Armenia, Belarus, Serbia, countries to WIPO administered transition countries ratifications/ Turkmenistan (539 ratifications by treaties accessions in the 29 transition countries cumulative end 2020) biennium II.1 Wider and more effective use of the PCT System for filing international patent applications, including by developing countries and LDCs No. of PCT applications 180,370 3.5% annual increase 2020 (preliminary): 179,775 (-0.3%) originating from transition and developed countries % of participants satisfied with 83% 80% of survey 94% (52% highly satisfied; 42% satisfied) the roving seminars respondents are satisfied or highly satisfied II.3 Wider and more effective use of the Hague System, including by developing countries and LDCs No. of Hague System applications 4,438 23% increase (2020) 2020 (preliminary): 4,245 (-0.3%) originating from transition and 9% increase (2021) developed countries II.5 Wider and more effective -

Member States

1/10/19 Total: 193 MEMBER STATES Afghanistan Democratic Republic of the Congo Albania Denmark Algeria Djibouti Andorra Dominica Angola Dominican Republic* Antigua and Barbuda Ecuador Argentina* Egypt* Armenia El Salvador Australia* Equatorial Guinea* Austria Eritrea Azerbaijan Estonia Bahamas Eswatini Bahrain Ethiopia Bangladesh Fiji Barbados Finland* Belarus France* Belgium Gabon Belize Gambia Benin Georgia Bhutan Germany* Bolivia (Plurinational State of) Ghana Bosnia and Herzegovina Greece* Botswana Grenada Brazil* Guatemala Brunei Darussalam Guinea Bulgaria Guinea-Bissau Burkina Faso Guyana Burundi Haiti Cabo Verde Honduras Cambodia Hungary Cameroon Iceland Canada* India* Central African Republic Indonesia Chad Iran (Islamic Republic of) Chile Iraq China* Ireland Colombia* Israel Comoros Italy* Congo Jamaica Cook Islands Japan* Costa Rica* Jordan Côte d'Ivoire* Kazakhstan Croatia Kenya Cuba Kiribati Cyprus Kuwait Czechia Kyrgyzstan Democratic People's Republic of Korea Lao People's Democratic Republic *Council Member State Latvia Rwanda Lebanon Saint Kitts and Nevis Lesotho Saint Lucia Liberia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Libya Samoa Lithuania San Marino Luxembourg Sao Tome and Principe Madagascar Saudi Arabia* Malawi Senegal Malaysia* Serbia Maldives Seychelles Mali Sierra Leone Malta Singapore* Marshall Islands Slovakia Mauritania Slovenia Mauritius Solomon Islands Mexico* Somalia Micronesia (Federated States of) South Africa* Monaco South Sudan Mongolia Spain* Montenegro Sri Lanka Morocco Sudan* Mozambique Suriname Myanmar Sweden -

Countering NATO Expansion a Case Study of Belarus-Russia Rapprochement

NATO RESEARCH FELLOWSHIP 2001-2003 Final Report Countering NATO Expansion A Case Study of Belarus-Russia Rapprochement PETER SZYSZLO June 2003 NATO RESEARCH FELLOWSHIP INTRODUCTION With the opening of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the Alliance’s eastern boundary now comprises a new line of contiguity with the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) as well as another geopolitical entity within—the Union of Belarus and Russia. Whereas the former states find greater security and regional stability in their new political-military arrangement, NATO’s eastward expansion has led Belarus and Russia to reassess strategic imperatives in their western peripheries, partially stemming from their mutual distrust of the Alliance as a former Cold War adversary. Consequently, security for one is perceived as a threat to the other. The decision to enlarge NATO eastward triggered a political-military “response” from the two former Soviet states with defence and security cooperation leading the way. While Belarus’s military strategy and doctrine remain defensive, there is a tendency of perceiving NATO as a potential enemy, and to view the republic’s defensive role as that of protecting the western approaches of the Belarus-Russia Union. Moreover, the Belarusian presidency has not concealed its desire to turn the military alliance with Russia into a powerful and effective deterrent to NATO. While there may not be a threat of a new Cold War on the horizon, there is also little evidence of a consolidated peace. This case study endeavours to conduct a comprehensive assessment on both Belarusian rhetoric and anticipated effects of NATO expansion by examining governmental discourse and official proposals associated with political and military “countermeasures” by analysing the manifestations of Belarus’s rapprochement with the Russian Federation in the spheres of foreign policy and military doctrine. -

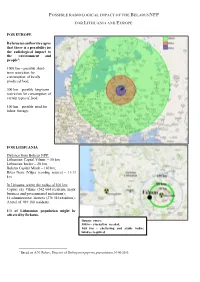

Possible Radiological Impact of the Belarus Npp For

POSSIBLE RADIOLOGICAL IMPACT OF THE BELARUS NPP FOR LITHUANIA AND EUROPE FOR EUROPE Belarusian authorities agree that there is a possibility for the radiological impact to the environment and people 1: 1000 km – possible short- term restriction for consumption of locally produced food; 300 km – possible long-term restriction for consumption of certain types of food; 100 km – possible need for iodine therapy. FOR LITHUANIA Distance from Belarus NPP: Lithuanian Capital Vilnius – 50 km; Lithuanian border – 20 km; Belarus Capital Minsk – 140 km; River Neris (Vilija) (cooling source) – 11-13 km. In Lithuania within the radius of 100 km: Capital city Vilnius (542 664 residents, major business and governmental institutions); 14 administrative districts (276 516 residents); A total of 919 180 residents. 1/3 of Lithuanian population might be affected by Belarus. Danger zones: 30km – evacuation needed; 100 km – sheltering and stable iodine intakes required. 1 Based on A.N. Rykov, Director of Belinipenergoprom, presentation, 16-06-2010. Distances from Belarus NPP site to: Capital of Lithuania Vilnius ~50 km; River Neris (Vilija) (cooling source) - ~11-13 km; Capital of Belarus Minsk ~ 140 km; Capitals within the range of 1000 km: Vilnius (~50 km); Minsk (~140 km); Riga (~300 km); Warsaw (~430 km); Tallinn (~550 km); Kiev (~560 km); Stockholm (~710 km); Copenhagen (~860 km); Berlin (~870 km). The main issues related to the nuclear and environmental safety of Belarus NPP project: Site selection and safety of site. The Espoo Convention requires to assess locational alternatives in the EIA report and to choose the project site as an outcome of the EIA procedure. -

How to Avoid the Iron Curtain Between the Eu and Belarus?

HOW TO AVOID THE IRON CURTAIN BETWEEN THE EU AND BELARUS? Policy brief – January 2008 The EU claims that its priority in relations with Belarus is not to isolate the country despite its harsh policy towards the Lukashenko regime, but instead to “engage with Belarusian society by further strengthening its support for civil society and democratisation” and further, to “intensify and facilitate people-to-people contacts”1. Notwithstanding this, after 1 January of 2008, Belarus is paradoxically the only EU Eastern neighbour whose citizens have to pay €60 for a single entry Schengen visa that approximately equals one third of the average monthly salary there. As the current authoritarian regime of Alyaksander Lukashenka has no sincere interest in maintaining good relations with the EU and the country does not even have a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement with the EU, it wasn’t possible to enter into negotiations with the former on a visa facilitation, in contrast to Moldova, Russia and the Ukraine which have already signed such agreements.2 The way in which the EU will addresses the visa relations with Belarus could well prove to be one of the most important matters concerning the future of Belarus and its citizens. Freedom of travel is a fundamental issue for future relations between the EU and its neighbours in general. The interpersonal relations built during overseas visits result in mutual bonds as well as in different forms of cooperation. Furthermore, they affect perception of the world and cause reflection on the conditions in one’s own country. At the first half of 90’s, that was true for the former Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland, where after years of the division of Europe into East and West, freedom to travel was one of the main factors which led to democratic change and the establishment of free market economies in these countries.