Playground for the Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Handful of Seeds, Seed Saving Curriculum

A Handful of Seeds S EED-SAVING AND S EED S TUDY FOR E DUCATORS Lessons linked to California Educational Standards Practical Information on Seed Saving for School Gardens History and Lore occidental arts & ecology center www.oaec.org A Handful of Seeds S EED S TUDY AND S EED S AVING FOR E DUCATORS by Tina Poles Occidental Arts and Ecology Center ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Project Manager and Lead Editor: Lisa Preschel Copy Editor: Karen Van Epen Reviewers: Carol Hillhouse, Jeri Ohmart,Abby Jaramillo, Susan McGovern, John Fisher,Yvonne Savio, Susan Stansbury Graphic Design: Daniela Sklan|Hummingbird Design Illustrations: Denise Lussier Photos: Doug Gosling, Jim Coleman, Rivka Mason, and Steve Tanguay The following people at Occidental Arts and Ecology Center contributed significant amounts of time and creativity to help develop the ideas in this publication: Doug Gosling, Brock Dolman, Dave Henson, Adam Wolpert, Michelle Vesser, and Renata Brillinger. Carson Price spun straw into gold by writing compelling grants to fund OAEC’s School Garden Program. Laurel Anderson, of Salmon Creek School, co-developed and taught many sections on seed saving in the School Garden Trainings, and Vanessa Passarelli, teacher and garden educator, shared many of her ideas about meaningful teaching. The following foundations have provided generous support to OAEC’s School Garden Teacher Training & Support Program since 2005: Chez Panisse Foundation, Community Foundation Sonoma County, Compton Foundation, Inc., David B. Gold Foundation, Foundation for Sustainability & Innovation, Grousbeck Family Foundation, Laurence Levine Charitable Fund, Lisa & Douglas Goldman Fund, L.J. Skaggs and Mary C. Skaggs Foundation, Morning Glory Foundation, San Francisco Foundation, Semilla Fund of the Community Foundation Sonoma County, Stuart Foundation,True North Foundation, and the Walter & Elise Haas Fund. -

Vincent Van Gogh Le Fou De Peinture

VINCENT VAN GOGH Le fou de peinture Texte Pascal BONAFOUX lu par l’auteur et Julien ALLOUF translated by Marguerite STORM read by Stephanie MATARD LETTRES DE VAN GOGH lues par MICHAEL LONSDALE © Éditions Thélème, Paris, 2020 CONTENTS SOMMAIRE 6 6 Anton Mauve Anton Mauve The misunderstanding of a still life Le malentendu d’une nature morte Models, and a hope Des modèles et un espoir Portraits and appearance Portraits et apparition 22 22 A home Un chez soi Bedrooms Chambres The need to copy Nécessité de la copie The destiny of the doctors’ portraits Les destins de portraits de médecins Dialogue of painters Dialogue de peintres 56 56 Churches Églises Japanese prints Estampes japonaises Arles and money Arles et l’argent Nights Nuits 74 74 Sunflowers Tournesols Trees Arbres Roots Racines 94 ARTWORK INDEX 94 index des œuvres Anton Mauve 9 /34 Anton Mauve PAGE DE DROITE Nature morte avec chou et sabots 1881 Souvenir de Mauve 1888 Still Life with Cabbage and Clogs Reminiscence of Mauve 34 x 55 cm – Huile sur papier 73 x 60 cm – Huile sur toile Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Pays-Bas Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Pays-Bas 6 7 Le malentendu d’une nature morte 10 /35 The misunderstanding of a still life Nature morte à la bible 1885 Still life with Bible 65,7 x 78,5 cm – Huile sur toile Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Pays-Bas 8 9 Souliers 1888 Shoes 45,7 x 55,2 cm – Huile sur toile The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA 10 11 Vue de la fenêtre de l’atelier de Vincent en hiver 1883 View from the window of Vincent’s studio in winter 20,7 x -

Discovery of the Place Where Van Gogh Painted His Last Masterpiece

This page was exported from - Digital meets Culture Export date: Thu Sep 30 2:46:05 2021 / +0000 GMT Discovery of the place where Van Gogh painted his last masterpiece img. Post card ?rue Daubigny, Auvers-sur-Oise' covered with the painting ?Tree Roots' (1890) by Van Gogh, ©arthénon, courtesy Van Gogh Museum. The discovery of the exact location where Vincent van Gogh painted his last artwork Tree Roots was made by Wouter van der Veen, the scientific director of the Institut van Gogh (Auvers-sur-Oise). Van der Veen found a post card dating from 1900 to 1910 featuring a scene including tree trunks and roots growing on a hillside. He has described and documented his discovery in a book, Attacked at the Roots, written specially for the occasion. Tree Roots is in the collection of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Highly plausible discovery Van der Veen submitted his discovery to Louis van Tilborgh and Teio Meedendorp, senior researchers at the Van Gogh Museum, almost immediately. Bert Maes, a dendrologist specialising in historical vegetation, was also consulted. Based on Van Gogh's working habits and the comparative study of the painting, post card and current condition of the hillside, the experts concluded that it is ?highly plausible' that the correct location has been identified. Wouter van der Veen (scientific director of the Institut van Gogh): ?Every element of this mysterious painting can be explained by observation of the post card and the location: the shape of the hillside, the roots, their relation to each other, the composition of the earth and the presence of a steep limestone face. -

Fall Parks and Programs Guide 2021

Guide FALL 2021 REGISTRATION BEGINS AUGUST 11 WWW.MONMOUTHCOUNTYPARKS.COM Saturday, September 18, 11:00 AM-5:00 PM BAYSHORE WATERFRONT PARK, PORT MONMOUTH Enjoy a day of coastal activities in this celebration of all things water! Get full details at www.MonmouthCountyParks.com. PM SUNDAY, OCTOBER 17, 11:00 AM-5:00 THOMPsoN PARK, LINCROFT An autumn day of funfor the entire family! Get full details at www.MonmouthCountyParks.com. TABLE OF CONTENTS Park System Spotlight 2-3 Adults 44-91 Active Adults 55+ . .44 Mark Your Calendar 4-5 Arts & Crafts . .45-56 Canine Classes . 56-57. Historic Happenings 6-8 Culinary Arts . 57-60. Education & Enrichment . .60-63 Families 9-20 Health & Wellness . 63-67. Arts & Crafts . 9-11 Horticulture . .67-72 Family Fun . 11-12. Nature . 73-77. Horticulture . .12 Outdoor Adventures . .78-82 Nature . 12-18. Performing Arts . 82-84. Outdoor Adventures . .19-20 Sports & Fitness . 84-91. Parent & Child 21-29 Equestrian 92 Arts & Crafts . .21 Culinary Arts . .22 Golf 93-97 Education & Enrichment . .22-23 Nature . .24 Therapeutic Recreation 98-99 Outdoor Adventures . .24-25 Play Groups . 26-29. Trips 99 Sports & Fitness . .29 Park System Locations 100-101 Kids & Teens 30-43 Arts & Crafts . .30-33 Registration Information 102-103 Culinary Arts . .34 Park Partners 104 Education & Enrichment . .35-37 Outdoor Adventures . .37-38 Performing Arts . 39-41. Sports & Fitness . 41-43. To register for programs starting August 11, call 732-842-4000, ext. 1, Monday-Friday from 8:00 AM-4:30 PM. For general information about your Monmouth County parks, call 732-842-4000, ext. -

Vincent Van Gogh Masterpieces of Art PDF Book

VINCENT VAN GOGH MASTERPIECES OF ART PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stephanie Cotela Tanner,Susie Hodge | 128 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | Flame Tree Publishing | 9781783612093 | English | London, United Kingdom Vincent Van Gogh Masterpieces of Art PDF Book Vincent van Gogh's Letters. Buy now. During a stay in the northern village of Nuenen in late through , the painter focused on agrarian scenes of peasants working the soil and weavers plying their craft. Wheatfield with Crows Vincent van Gogh, Dr Julian Beecroft. Vincent van Gogh died at the age of 37 bringing his career as a painter to an end, but beginning his legacy as the great painter of the future who inspired the world. You can learn more about our use of cookies here. The Starry Night. In the foreground of the painting, hyacinths in white, blue, pink and golden hues fill garden boxes that lead to eye toward a distant hillside and a sky filled with white clouds. Home Contact us Help Free delivery worldwide. You follow the on-going search of an artist who was constantly trying to improve himself. Book ratings by Goodreads. His artistic genius is often overshadowed by those who see his paintings as mere visual manifestations of his troubled mind. Written c. The Sower Vincent van Gogh, Book tickets. Nor could he possibly ever have dream that he would be an enduring source of inspiration for subsequent generations of artists. If you became a painter, one of the things that would surprise you is that painting and everything connected with it is quite hard work in physical terms. -

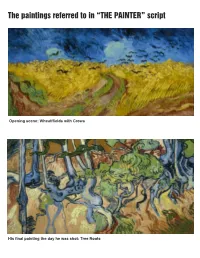

The Paintings Referred to in “THE PAINTER” Script

The paintings referred to in “THE PAINTER” script Opening scene: Wheatffields with Crows His final painting the day he was shot: Tree Roots The YELLOW HOUSE where he died, cafe on first floor Dr. Gachet Theo Photo of Joanna, Theo’s wife and son Sunflowers Irises Starry Night over the Rhone ... to be overlaid with the NYC skyline Signature Vincent was tired of people mispronouncing his last name so he would only sign paintings Self Portrait he liked as “Vincent” The Ravoux Inn, the “yellow house” in Auvers-sur-Oise, France when Vincent stayed and died there ... and same place today. Vincent’s actual room at the Ravoux Inn in Auvers-sur-Oise The FINAL SUMMER of THE PAINTER Vincent spent the last 70 days of his life at the yellow building called the Ravoux Inn. Given to absolute regimen, he would get up every morning at 5 AM and paint all day, coming back to the Inn at his regular time each evening for his dinner at the downstairs café. He would then go up to his room and paint some more. He was charged about 3 francs a night and while there befriended the owners teenage daughter. After con - stant requests, he finally painted the young girl and gave her the canvas as a gift. During that summer he created more than 80 paintings and 64 sketches before the shooting, stumbling back to his room and dying two days later with his brother Theo at his side on July 29, 1890. THE GRAVES: Vincent and Theo after Joanna interred her husband and brought him to Vincent’s side. -

Tragic Destiny in the Life and Death of Vincent Van Gogh By

Tragic Destiny in the Life and Death of Vincent van Gogh By Richard A. Hughes M.B. Rich Professor of Religion Lycoming College 700 College Place Williamsport, PA 17701-5192 USA 2 The aim of this essay is to interpret selected aspects of the life and death of Vincent van Gogh in light of a new biography. On October 18, 2011 two American scholars published a detailed and comprehensive biography of the artist, consisting of nearly 900 pages with small print and correlated with online footnotes (Naifeh and Smith 2011). This magisterial work will surely become the definitive biography of the painter. The authors present new evidence that refutes previous biographies, making them misleading or obsolete. For example, previous studies presumed that van Gogh died by suicide, but that position can no longer be maintained (cf. Blumer 2002; Meissner 1992; Nagera 1967). My interpretation is based upon the work of Leopold Szondi, a Hungarian-Swiss psychiatrist who established a monumental system of psychiatry called Schicksalsanalyse or the “analysis of destiny.” As a psychiatric geneticist, Szondi discovered the familial unconscious and synthesized it with psychopathology, ego psychology, and psychotherapy. He organized his system in terms of the concept of destiny which he defined as “the totality of all inherited existential possibilities” that one chooses and enacts (Szondi 1968: 21). The existential possibilities emerge from the familial unconscious, and the individual selects them either compulsively or relatively freely while acting out a pattern of behavior. The main choices are those of marriage, vocation, friendship, and to a certain extent illness and mode of death. -

Vincent Van Gogh's Christian Faith and How It Influenced His Life And

Vincent van Gogh’s Christian Faith and How it influenced his Life and Art Yongnam Park School of Human Development Dublin City University Supervisors: Dr. Thomas Grenham Dr. Andrew O’Regan Dr. Mary Ivers A dissertation in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Master of Philosophy (MPhil) June 2017 Declaration I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Master of Philosophy is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ID No: 16116887 Date: June 2017 I Acknowledgments I am indebted to many people who have assisted me in different ways because a MPhil thesis is not only my project. Most of all, I would like to express my gratitude and sincere thanks to my supervisors Dr. Thomas Grenham, Dr. Andrew O’Regan, and Dr. Mary Ivers for their excellent guidance and insightful suggestions. Without their help and encouragement the thesis would be diminished. Particularly, I’d like to thank my friend for her help and interest, especially to thank Estelle Feldman who proofread my text with great patience. I would like to thank Rev. Des Bain who taught me what is a real minster’s life and leadership. Without his prayer and help, I can’t do anything in Ireland. -

Van Gogh Lecture Jaap Van Duijn

Vincent and his changing image of God Lecture by Jaap van Duijn, 2019 We will look into the different phases in the life of Vincent van Gogh. His religious experience and his image of God in addition to the artistic development of Vincent van Gogh's work. Sometimes they go together with his change of residence. Emo Verkerk, Vincent and his mother • That Van Gogh still inspires people needs no explanation. For example, look at the painting that modern portrait painter Emo Verkerk made in honor of Van Gogh's 125th year of death. So 2015. The painting is part of a series of Van Gogh portraits and depicts the strictly Reformed mother Anna and Vincent as an art dealer in London (based on one of the few photos known by Vincent). It shows well the relationship between Vincent and his mother. • Vincent's enormous drive and passion for painting is known. Many people, including myself, have traveled all places where Vincent lived and worked out of fascination for the artist. The website vangoghroute.nl was created from this. All places of residence are described on this website. The development was done by Stichting Gifted Art By Judith de Bruijn, art historian. 1 2 Van Gogh family The family: father Theo van Gogh the pastor and mother Anna Carbentus. The children: Vincent, Anna, Theo, Lies, Wil and Cor Vincent's birth certificate First of all, a look at his childhood: • Vincent is born on March 30, 1853. • He lives with his family in the rectory on the Markt in Zundert. -

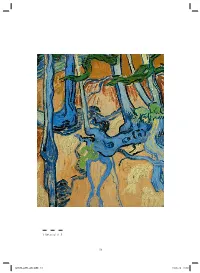

Van Gogh's Tree Roots up Close

1. Detail of ill. 3 54 120046_p001_208.indd 54 31-05-12 13:38 Van Gogh’s Tree roots up close Bert Maes and Louis van Tilborgh Tree roots is undoubtedly the most intriguing painting from Vincent van Gogh’s Auvers period (ills. 1, 3). This close-up view of the bases of trees shows a jungle of twisted roots, trunks, branches and leaves. Enlarging and bringing forward details that had traditionally been relegated to the background had become a stock part of Van Gogh’s visual vocabulary since his discovery of the world of Japanese prints (ill. 2), but unlike a work such as Long grass with butterfl ies (ill. 4), which is also a close-up, the viewer of Tree roots ‘is hard put to identify the subject as a whole’, as Jan Hulsker wrote in 1980.1 The scene is regarded virtually without exception as ‘almost abstract’ due to ‘the extreme stylisation’.2 ‘Ambiguous, stylized, vitalistic, life-affi rming, antinaturalistic yet palpably organic: a kind of prototype for an Art Nouveau frieze’,3 was Ronald Pickvance’s reaction to it. In this he was following Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, who had asserted six years previously that ‘intima- tions of the elegant stylizations of the international Art Nouveau movement’ were ‘obviously present’ in the work.4 It displayed ‘one of the most extraordinary de- grees of a decoratively conceived quasi-abstraction which can be discovered in his total oeuvre’, and it should therefore be ‘celebrated for the prediction of twentieth- century style which it represents’. Whether we should judge art by its value for ‘the Road to Flatness’, as many regard the origins of the history of modern art,5 is very much the question, but leaving that aside, does the signifi cance of Tree roots lie solely in its formal charac- teristics, and are they really that extreme? The scene may look fairly abstract and diffi cult to decipher compared with other works from the same period, but the stylistic devices (the omission of a horizon line due to the extreme close-up, the 55 120046_p001_208.indd 55 31-05-12 13:38 VAN GOGH STUDIES 4 / BERT MAES AND LOUIS VAN TILBORGH 2. -

Press Release Van Gogh, Rousseau, Corot: in the Forest Forest-Filled

Press Release Van Gogh, Rousseau, Corot: In the Forest Forest-filled summer exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum from 7 July to 10 September Amsterdam, 6 July 2017 This summer the Van Gogh Museum is presenting lesser known paintings of woodland views and landscapes by Vincent van Gogh alongside works by French landscape painters such as Théodore Rousseau and Camille Corot in a show titled Van Gogh, Rousseau, Corot: In the Forest. This exhibition explores a neglected aspect of Van Gogh’s oeuvre and shows how his vision of nature was shaped in part by the artists of the School of Barbizon. These innovative painters depicted nature in the loose style characteristic of the landscapes they made in the Forest of Fontainebleau, near the village of Barbizon, just south of Paris. The exhibition Van Gogh, Rousseau, Corot: In the Forest presents 34 works from the Van Gogh Museum and The Mesdag Collection, as well as three exceptional loans: Sunset at Montmajour (the most recently discovered of Van Gogh’s paintings), Pollard Birch from the Van Lanschot Collection and a painting from a private collection, Windswept Trees near Loosduinen, on which Van Gogh’s fingerprints can be seen with the naked eye. Throughout the summer, including the duration of Van Gogh, Rousseau, Corot: In the Forest, the museum is also open on Saturday evenings. Unidealised representation of nature Van Gogh, Rousseau, Corot: In the Forest presents woodland views by Vincent van Gogh in the context of paintings from the School of Barbizon. Until the 1830s it was customary for artists to paint indoors, in the studio; it was mainly sketching that was done outside. -

Van Gogh, Nature, and Spirituality

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Art and Art History Honors in the Major Theses Spring 2021 Van Gogh, Nature, and Spirituality Emma Krall [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.rollins.edu/honors-in-the-major-art Recommended Citation Krall, Emma, "Van Gogh, Nature, and Spirituality" (2021). Art and Art History. 2. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/honors-in-the-major-art/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors in the Major Theses at Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Art History by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VAN GOGH, NATURE, AND SPIRITUALITY APRIL 1, 2021 EMMA KRALL Honors in the Major Thesis Advisor- Dr. Susan Libby 1 Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................ 2 Introduction .................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1- Religion and Family ..................................................................... 7 Chapter 2- The Beginnings of Life as An Artist .......................................... 13 Chapter 3- Turning Towards Nature ............................................................ 21 Chapter 4- Wheat Fields ............................................................................... 26 Chapter 5- Millet and The Sower .................................................................