I Reinventing Infrastructure Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Operations and Maintanence Syetems for Metro Railways

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF URBAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT OF THE SUB-COMMITTEE ON OPERATIONS AND MAINTANENCE SYETEMS FOR METRO RAILWAYS NOVEMBER 2013 Sub-Committee on Operation & Maintenance Practices Ministry of Urban Development Final Report PREFACE 1) In view of the rapid urbanization and growing economy, the country has been moving on the path of accelerated development of urban transport solutions in cities. The cities of Kolkata, Delhi and Bangalore have setup Metro Rail System and are operating them successfully. Similarly the cities of Mumbai, Hyderabad and Chennai are constructing Metro Rail system. Smaller cities like Jaipur, Kochi and Gurgaon too are constructing Metro Rail system. With the new policy of Central Government to empower cities and towns with more than two million population With Metro Rail System, more cities and towns are going to plan and construct the same. It is expected that by the end of the Twelfth Five Year Plan, India will have more than 400 Km of operational metro rail network (up from present 223 Km Approximate). The National Manufacturing Competitiveness Council (NMCC) has been set up by the Government of India to provide a continuing forum for policy dialogue to energise and sustain the growth of manufacturing industries in India. A meeting was organized by NMCC on May 03, 2012 and one of the agenda items in that meeting was “Promotion of Manufacturing for Metro Rail System in India as well as formation of Standards for the same”. In view of the NMCC meeting and heavy investments planned in Metro Rail Systems, Ministry of Urban Development (MOUD) has taken the initiative of forming a Committee for “Standardization and Indigenization of Metro Rail Systems” in May 2012. -

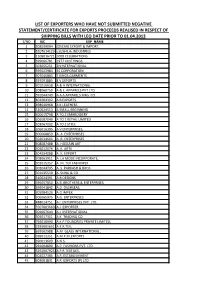

List of Exporters Who Have Not Submitted Negative

LIST OF EXPORTERS WHO HAVE NOT SUBMITTED NEGATIVE STATEMENT/CERTIFICATE FOR EXPORTS PROCEEDS REALISED IN RESPECT OF SHIPPING BILLS WITH LEO DATE PRIOR TO 01.04.2013 S/NO IEC EXP_NAME 1 308039084 (OSCAR) EXPORT & IMPORT, 2 5207014129 ┐SUSHILA┐INDUSTRIES 3 1309016721 1008 CELEBRATIONS 4 399066781 1977 KLOTHINGS 5 303055251 3N INTERNATIONAL 6 399023984 3S CORPORATION 7 307046885 7 KINGS GARMENTS 8 397091885 8 V EXPORTS 9 301016658 A & A INTERNATIONAL 10 308060750 A & L APPARELS PVT LTD 11 591044749 A A A APPARELS MFG. CO. 12 402004302 A B EXPORTS 13 498040968 A K LEATHERS 14 510024513 A SMALL BEGINNING 15 300015798 A TO Z EMBROIDERY 16 306087049 A TO Z RETAIL LIMITED 17 503067032 A TO Z STYLE 18 206016395 A V ENTERPRISES, 19 300068859 A. A. ENTERPRISES 20 304034606 A. B. ENTERPRISES 21 308087488 A. HOSSAIN ART 22 304012076 A. K. ARTS 23 304034088 A. K. EXPORT 24 308063911 A. LA MODE INCORPORATE, 25 303015357 A. M. TEX FAB IMPEX 26 302044795 A. S. PARKASH & BROS 27 301035539 A. SUNIL & CO. 28 310024391 A.B DESIGNS 29 395057850 A.B. BROTHERS & ENTERPRISES 30 399041842 A.D. OVERSEAS, 31 305084526 A.D.IMPEX 32 306065975 A.G. ENTERPRISES 33 488014751 A.I. ENTERPRISES PVT. LTD. 34 3507003660 A.J. EXPORTER 35 304067644 A.J. INTERNATIONAL 36 304017311 A.K. TRADING CO. 37 792010990 A.K.P.FOUNDRIES PRIVATE LIMITED, 38 3295001651 A.K.R.TEX, 39 695002988 A.M. GLASS INTERNATIONAL , 40 399013351 A.M.P.M.EXPORTS 41 390013609 A.N.S. 42 291004890 A.P. FASHIONS PVT. -

Bulletin 27 (1998)

Bulletin of the COUNCIL of UNIVERSITY CLASSICAL DEPARTMENTS Bulletin 27 (1998) Contents Quality Control Christopher Stray Attractive and Nonsensical Classics: Oxford, Cambridge and Elsewhere Christopher Rowe Chairman's Report 1998 Geoffrey Eatough Classics at British Universities, 1997-8: Statistics CUCD Conference Panel, Lampeter 1998: "Graduateness" Charlotte Roueché Greek after Pentecost: The Arguments for Ancient Language 1 Quality Control As anticipated, this has been a busy year for CUCD, and this year's Bulletin for the first time includes a Chairman's Report on the items that have preoccupied us most over the twelve months since Council. As well as a testimony to the energy and efficacy of our current Chair, it reflects CUCD's ever-great enmeshment qua national subject body in the issues of policy and quality we need to influence if we are to defend the things that make our field unique and uniquely resistant to easily assimilation into uniform models of academic structure and outcomes. It remains CUCD strategy here not merely to stay abreast, but where possible to outflank. Even so, the goalposts have been not merely mobile this year but positively skittish, with potentially far-reaching changes in the structures of research funding and academic assessment. We hope that a report from the Chair will help to keep colleagues up to speed with national and subject-specific developments. In this context, the Bulletin retains an especially important role as a forum for current thinking on aims and methods of classical language teaching. Here Charlotte Roueché has recently been pressing a powerfully-argued case for a new role for Greek and Latin as the vehicles for formal language study of a kind largely vanished from the teaching of English and modern languages in schools, but increasingly essential for precisely the new disciplines that are moving towards the centre of the curriculum. -

Can East Asia Weather a US Slowdown?

About the Paper The ongoing slowdown in the economy of the United States (US) has sparked increasing concerns over the short-term growth prospect of East Asia. Using the Oxford Economics’ Global Model, Cyn-Young Park examines the possible impacts on East Asia of a sharper and longer US slowdown than is currently anticipated in the Asian Development Outlook 2007. The simulation results suggest that a US slowdown on its own would not meaningfully derail East Asia's strong growth. However, in case of significant spillovers from the US slowdown through financial instability and a hard landing in investments in the People’s Republic of China, different growth stories of East Asia may unfold. ERD Working Paper ECONOMICS AND RESEARCH DEPARTMENT About the Asian Development Bank SERIES The work of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) is aimed at improving the welfare of the people in Asia and the Pacific, particularly the 1.9 billion who live on less than $2 a day. Despite many success stories, Asia and the Pacific remains home to two thirds of the world’s poor. ADB is a multilateral development No. finance institution owned by 67 members, 48 from the region and 19 from other parts of the globe. ADB’s vision is a region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their citizens. 95 ADB’s main instruments for providing help to its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, technical assistance, grants, guarantees, and equity investments. ADB’s annual lending volume is typically about $6 billion, with technical assistance usually totaling about $180 million a year. -

Internal Paper

BCN IC hPERS AttAlns coMtwsstoil 0F THE EUR0PEAI| coilitutfftEs o 0|REGT0RATE-GEIIERAL ron Ecotloilllc AtIo FltlA]lclAt No. 39 JuLy 1985 AnaLysis of the stabi Lisation mechanisms of macroeconomic modeLs : a comparison of the EuroLink modets A. BUCHER and V- R0SSI InternaL PaPer "Economic Papers" are written by the Staff of the Directorate-GeneraL for Economic and flnanciaL Affairs, or by experts working in association with them. The "Papers" are intended to increase awareness of the technicaI work being done by the staff and to seek comments and suggestions for further anatyses. They may not be quoted without authorisation. Viel'ls expressed represent excLusiveIy the positions of the author and do not necessari Ly correspond with those of the Commission of the European Communities. Comments and enquiries shoutd be addressed to The Directorate-GeneraI for Economic and FinanciaL Affairs, Commission of the European Communities, 200, rue de ta Loi 1049 BrusseLs, BeLgium ECONOMIC PAPERS No. 39 July 1985 Analysis of the stabilisation mechanisms of macroeconomic models : a comparison of the Eurolink models A. BUCHER and V. ROSSI Internal Paper This paper is only available in English II/92/85-EN ( 1) Contents I Introduction II Evaluating the dominant mechanisms of macroeconomic models III The Expansionary process II1.1 Demand component sensitivity 111.2 Generation of income through labour market adjustment IV Neutrality of the distribution of income IV.l Primary distribution: wage-price nexus IV.2 Redistribution: sectoral transfers V Other constraints to growth V.l Domestic constraints V.2 Open economies and external constraints VI Conclusion Appendix 1: Standardised description of models Appendix 2: Detailed simulation results Bibliography I. -

The Crisis Management of the ECB

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Breuss, Fritz Working Paper The Crisis Management of the ECB WIFO Working Papers, No. 507 Provided in Cooperation with: Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), Vienna Suggested Citation: Breuss, Fritz (2016) : The Crisis Management of the ECB, WIFO Working Papers, No. 507, Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/129056 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu ÖSTERREICHISCHES INSTITUT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTSFORSCHUNG WORKING PAPERS The Crisis Management of the ECB Fritz Breuss 507/2016 The Crisis Management of the ECB Fritz Breuss WIFO Working Papers, No. 507 January 2016 Abstract A sequence of crises – the global financial crisis in 2008, the "Great Recession" in 2009 and the subse- quent Euro crisis – constituted a major challenge for policy makers. -

Solent Economic Outlook

Solent LEP Technical annex March 2014 A report prepared for Solent LEP Contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview ..................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Oxford Economics’ suite of models ............................................................ 1 1.3 Local baseline / policy off forecasting......................................................... 2 1.4 Population and migration assumptions ...................................................... 3 2 An overview of the model approach .............................................. 5 2.1 Variable, geographical and time period coverage .............................................................................................................. 5 2.2 Scenario model framework ......................................................................... 6 2.3 An input-output framework ......................................................................... 7 2.4 Direct impacts ............................................................................................. 7 2.5 Indirect and induced effects ....................................................................... 8 2.6 Who takes the jobs? ................................................................................... 8 Solent LEP Technical Annex 1 Introduction 1.1 Overview This report sets out the technical elements of the Solent LEP Forecast Model. It provides insight into the relationships -

Winds SC Diifdngtothewe^T^ This After*

2 ; , 1 0 0 6 V i S J P H IC S = OK 5 1 i ‘ 0 ThleT UT 3 i 1 0 7 gTw in Falls, Ida!laho/91st year, No. 24243' ■. Friday,A\ugust30, tin 1996 m50 ccntj:nts - ''G o o d m oDRNING: Z k ; .'W e a t h e r Vdounners necall (Goodiing atthlete Today; Sunny w ithisbuthwinds SC diifdngtothewe^t^ this after* . B M k noon. in th ei lclow 90s. Lows uestions corm e to fore 50 to 55 degrees. PageA2 ■ Qu ^bolOut crash faatal to 3 M a g ic V a l lu e e y ' ; H ByLizWrijWright. ■ ' . I ic c d ,” - TTieTlmeUw»Wew«’~" " - ---------- • I said Dow)owcIl. D c m a r a y , GOODODING - As mourners I ding T hursda>day remembered high -jriW Countyi cocoro- ll fof o tb a ll p la y e r Clay I t ® ner. “Il’s:t’s not1 ek id s. K naup,p, somc braced for thc ' able questions about the s ru n I crash thaithat killed K naup and two sig n s, otherGocGooding teen-dgers. W hatiiIt if K naup h ad braked on c ra sh the lonel;nely country intersection a l s o ^ 'kkille u i d k e' Abortion polftlcs: PPro-life n and just befocforc m idnight, os policc Clay Knaup M i k 1 1 1 ^ vidence suggested he W ilk inn sc o n , pnniioice booths aattheIWin t ^ failed to do? Apparently, Knaup 18,1 an d B obbiJoM iller,17.T7. -

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS of DEBATES (Proceedings Other Than

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES (Proceedings other than Questions & Answers) ______ Monday, July 14, 2014 / Ashadha 23, 1936 (Saka) ______ *MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 (i) SHRI ASHWINI KUMAR CHOUBEY laid a statement regarding need to provide the allocated share of water of Son River to Bihar under Bansagar agreement and initiate pending work in Kadvan Reservoir Project. (ii) SHRI RAVINDER KUSHAWAHA laid a statement regarding need to repair the bridge over river Ghaghara connecting Deoria district and Ballia district of Uttar Pradesh. (iii) SHRI RAMDAS C. TADAS laid a statement regarding need to provide a special package for providing water for drinking and irrigation purposes in Maharashtra particularly in Wardha Parliamentary Constituency in the state. * Laid on the Table as directed by the Speaker. (iv) DR. MANOJ RAJORIA laid a statement regarding need to implement Chambal Lift Project in Karauli-Dholpur Parliamentary Constituency, Rajasthan. (v) SHRI CHHEDI PASWAN laid a statement regarding need to explore mineral reserves in Sasaram Parliamentary Constituency, Bihar. (vi) SHRIMATI RAMA DEVI laid a statement regarding need to initiate acquisition of land for construction of road along India-Nepal border in Sheohar Parliamentary Constituency, Bihar. (vii) SHRI SANJAY DHOTRE laid a statement regarding need to expedite the gauge conversion of the Ratlam-Fatehabad-Indore-Mhow-Khandwa- Amalkhurd-Akot-Akola Section. (viii) SHRI A.T.NANA PATIL laid a statement regarding need to fix remunerative price of agricultural produce keeping in view the cost of inputs involved. (ix) SHRI DILIPKUMAR MANSUKHLAL GANDHI laid a statement regarding need to improve power situation in Maharashtra State. (x) SHRI KAMLESH PASWAN laid a statement regarding need to declare Dughdeswarnath Temple at Rudrapur in Deoria district, Uttar Pradesh as a tourist place and provide basic facilities at the temple site. -

Lucknow, State Capital of Uttar Ity of the Cases Have Not Been Continued on Page 11 with Her Friends

* # @ / "& ! $!A " $!A " A VRGR $"#(!#1')VCEBRS WWT!Pa!RT%&!$"#1$# 78 (7" +309 +$()(+)& ,+- .$+-/0 & " ( 1 157 5 471/7 *6/76 4E7&**4. 16 D. /74 4 56* *&14 1671 76014 6F7G 7/*O 1**6 *( 7/*016 1D76 6 6 4 16 1& 16/01 /71/6 D/711/ E)1D1/1 4 56 8:9 77& <?> B1 ! 7 1" ! " /- 42/ 44: +9 1 # $#%$ &# &161 Prime Minister Narendra Modi who addressed three more ral- oters of Bihar defied coro- lies in the State on Wednesday Vnavirus as the provisional did not mention Chirag’s name turnout of 54.26 per cent in the or said anything to clear the air first phase of the Assembly among the cadres of the BJP 4 56* may quit Mayawati’s party and polls for 71 seats matched the about speculation that Chirag join the SP. figure of 2015. It is expected enjoys the blessings of the BJP he nomination of BSP can- But an BSP MLA said the that the final percentage could big wigs. Tdidate Ramji Gautam for party has challenged their affi- go still higher as the Election This is the first major elec- the Rajya Sabha was held valid davit, saying the four MLAs Commission is updating the tion being conducted amid the on Wednesday even after four were present at the time of the data with more inputs from 71 raging Covid-19 pandemic in party MLAs claimed that their nomination on Monday. constituencies spread across the country. According to the signatures on it were forged . He said the party had sent 16 districts. -

High Speed Railway Project Development and Regional Accessibility Improvement: the First Experience in India

FACULTY OF CIVIL AND INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING Master Degree in Transport System Engineering Thesis High Speed Railway Project Development and Regional Accessibility Improvement: The First Experience in India Supervisor: Candidate: Prof. Eng. Antonio Musso Amal Kuzhiparambil Purushothaman Co-Supervisor: N° 1722321 Dr. Eng. Cristiana Piccioni Academic Year 2018/2019 2 Table of contents Summary 1. Introduction 1.1 Study purpose 1.2 Research background 1.3 Research methodology 1.4 Key issues 2. The Reference framework 2.1 Definition of high-speed rail 2.2 HSR benefits 2.3 HS Rail around the world 2.3.1 Japan 2.3.2 Italy 2.3.3 France 2.3.4 Germany 2.3.5 Spain 2.3.6 China 3. The accessibility concept 3.1 Definition of accessibility 3.2 Accessibility indicators 3.3 A basic benchmarking exercise 4. Accessibility and HSR projects: an insight into international experiences 4.1 The Madrid-Barcelona HSR case study, Spain 4.2 The China HSR case study 4.3 The Seoul HSR case study, Korea 4.4 Brisbane - Melbourne proposed HSR, Australia 5. Building an accessibility indicators framework 5.1 Identification of Accessibility indicators 5.2 A selection of accessibility indicators 5.2.1 Weighted average travel times (Location indicator) 5.2.2 Economic potential 3 5.2.3 Daily accessibility indicator 5.2.4 Economic accessibility 6. Pilot study: the Mumbai – Ahmedabad HSR project 6.1 HSR project background 6.1.1 Necessity of HSR System in India 6.2 Major cities affected by the project 6.2.1 Mumbai 6.2.2 Surat 6.2.3 Vadodara 6.2.4 Ahmedabad 6.3 HSR Project overview 6.3.1 Basic characteristics 6.3.2 Stations 6.3.3 Train operation plans 6.4 Accessibility assessment 6.4.1 Calculation and evaluation of indicators 6.4.2 Weighted average travel times (location indicator) 6.4.3 Economic potential 6.4.4 Daily accessibility indicator 6.4.5 Economic indicator 7.