Empowering Community Resilience to Climate Change in Cameroon Using Technology-Enhanced Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modele-Mc2-Depliant.Pdf

Pourqoui les MC² • La pauvreté est essentiellement rurale (plus de 60% de la population) ; • Plus de 50% des pauvres (personnes vivant avec moins d’un dollar par jour) vivent en Afrique • Les populations rurales n’ont presque pas accès aux services financiers qui permettraient d’améliorer leurs conditions de vie et développer leur communauté. Le grenier de la communauté • Les zones rurales regorgent d’un grand potentiel en ressources naturelles, agropastorales, etc. encore très peu valorisées Le bien-être de la famille par la femme Listes des MC² opérationnelles au cameroun au 31 octobre 2018 1. MC² de Baham 25. MC² Fongo-Tongo 49. MC² de Baré 73. MC² de Fundong 97. MC² de Mindif 2. MC² de Manjo 26. MC² de Njombé 50. MC² de Bertoua 74. MC² de Tibati 98. MC² Bamenkombo 3. MC² de Melong 27. MC² de Mbankomo 51. MC² de Banyo 75. MC² de Mbang 99. MC² Kedjom Keku 4. MC² Penka-Michel 28. MC² Kribi- Campo 52. MC² de Mokolo 76. MC² de Belo 100. MC² de Ngong 5. MC² de Bandjoun 29. MC² de Loum 53. MC² de Makak 77. MC² de Okola 101. MC² de Bangoua Le modèle MC² 6. MC² de Badjouma 30. MC² Esse-Awae 2 54. MC² de Bangang 78. MC² Tongo Gandima 102. MC² de Tonga 7. MC² de Bafia 31. MC² de Ekondo Titi 55. MC² de Santa 79. MC² Abong-Mbang 103. MC² de Ngoro Une approche endogène 8. MC² de Bamendjou 32. MC² de Kekem 56. MC² de Bamena 80. MC² de Yabassi 104. MC² de Ndziih 9. -

Project : Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2

PROJECT : TRANSPORT SECTOR SUPPORT PROGRAMME PHASE 2 COUNTRY : REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Joseph Kouassi N’GUESSAN, OITC.1/CMFO Chief Transport Engineer Jean-Pierre KALALA, Chief OITC1/CDFO Socio-Economist Modeste KINANE, Principal ONEC.3 Environmentalist Jean Paterne MEGNE EKOGA, OITC.1 Team Members Senior Transport Economist Project Samuel MBA, Senior Transport OSHD.2/CMFO Team Engineer S. KEITA, Principal Financial OITC1 Management Specialist C. DJEUFO, Procurement ONEC.3 Specialist Sector Division Manager J. K. KABANGUKA OITC.1 Resident Representative R. KANE CMFO Sector Director A. OUMAROU OITC Regional Director M. KANGA ORCE SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Programme Name : Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2 SAP Code: P-CM-DB0-015 Country : Cameroon Department : OITC Division : OITC-1 1. INTRODUCTION This document is a summary of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of the Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2 which involves the execution of works on the Yaounde-Bafoussam-Bamenda road. The impact assessment of the project was conducted in 2012. This assessment seeks to harmonize and update the previous one conducted in 2012. According to national regulations, the Yaounde-Bafoussam-Babadjou road section rehabilitation project is one of the activities that require the conduct of a full environmental and social impact assessment. This project has been classified under Environmental Category 1 in accordance with the African Development Bank’s Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) of July 2014. This summary has been prepared in accordance with AfDB’s environmental and social impact assessment guidelines and procedures for Category 1 projects. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

Prevalence of Geo-Helminths And

ISSN: 2643-461X Cedric et al. Int J Trop Dis 2020, 3:036 DOI: 10.23937/2643-461X/1710036 Volume 3 | Issue 2 International Journal of Open Access Tropical Diseases RESEARCH ARTICLE Prevalence of Geo-Helminths and Evaluation of Single Dose of Albendazole (400 mg) among School Children in Poumougne, Western Region, Cameroon Yamssi Cedric1*, Kamga Simo Sabrina Lynda2, Noumedem Anangmo Christelle Nadia3 and Check for Vincent Khan Payne2 updates 1Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Bamenda, P.O. Box 39 Bambili, Cameroon. 2Department of Animal Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Dschang, P.O. Box 067, Dschang, Cameroon 3Department of Microbiology, Hematology and Immunology Faculty of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Dschang, P.O. Box 96, Dschang, Cameroon *Corresponding author: Yamssi Cedric, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Bamenda, PO Box 39 Bambili, Cameroon, Tel: (237)-677413547 Abstract and trichuriasis. This study may contribute to the fight against intestinal helminthiasis among school age children Background: Soil Transmitted Helminths (STHs) also in Bandjoun. called Geo-helminths are endemic in rural areas of devel- oping countries. This study was conducted to determine Keywords the prevalence of Geo helminths, their risk factors and an evaluation of a single dose of Albendazole 400 mg among STH, Prevalence, Infection, Intensity, Poumougne, Alben- infected School Children. dazole, School age children Methodology: Three High schools and Colleges, three Pri- Abbreviations mary schools and a Nursery School were selected at ran- ALB: Albendazole; CR: Cure Rate, EPG: Egg per gram of dom for sample collection. Stool was collected from each faeces; ERR: Egg Reduction Rate; NTDs: Neglected Tropi- subject and analyzed using floatation technique and Mc- cal Disease; SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Science; Master method respectively. -

Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Trifoliate Yam (Dioscorea

Siadjeu et al. BMC Plant Biology (2018) 18:359 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1593-x RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Genetic diversity and population structure of trifoliate yam (Dioscorea dumetorum Kunth) in Cameroon revealed by genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) Christian Siadjeu* , Eike Mayland-Quellhorst and Dirk C. Albach Abstract Background: Yams (Dioscorea spp.) are economically important food for millions of people in the humid and sub- humid tropics. Dioscorea dumetorum (Kunth) is the most nutritious among the eight-yam species, commonly grown and consumed in West and Central Africa. Despite these qualities, the storage ability of D. dumetorum is restricted by severe postharvest hardening of the tubers that can be addressed through concerted breeding efforts. The first step of any breeding program is bound to the study of genetic diversity. In this study, we used the Genotyping-By- Sequencing of Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (GBS-SNP) to investigate the genetic diversity and population structure of 44 accessions of D. dumetorum in Cameroon. Ploidy was inferred using flow cytometry and gbs2ploidy. Results: We obtained on average 6371 loci having at least information for 75% accessions. Based on 6457 unlinked SNPs, our results demonstrate that D. dumetorum is structured into four populations. We clearly identified, a western/ north-western, a western, and south-western populations, suggesting that altitude and farmers-consumers preference are the decisive factors for differential adaptation and separation of these populations. Bayesian and neighbor- joining clustering detected the highest genetic variability in D. dumetorum accessions from the south-western region. This variation is likely due to larger breeding efforts in the region as shown by gene flow between D. -

Programmation De La Passation Et De L'exécution Des Marchés Publics

PROGRAMMATION DE LA PASSATION ET DE L’EXÉCUTION DES MARCHÉS PUBLICS EXERCICE 2021 JOURNAUX DE PROGRAMMATION DES MARCHÉS DES SERVICES DÉCONCENTRÉS ET DES COLLECTIVITÉS TERRITORIALES DÉCENTRALISÉES RÉGION DE L’OUEST EXERCICE 2021 SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de Montant des N° Désignation des MO/MOD N° Page Marchés Marchés 1 Services déconcentrés régionaux 14 526 746 000 3 2 Communauté Urbaine de Bafoussam 18 9 930 282 169 5 Département des Bamboutos 3 Services déconcentrés 6 177 000 000 7 4 Commune de Babadjou 12 350 710 000 7 5 Commune de Batcham 8 250 050 004 9 6 Commune de Galim 6 240 050 000 10 7 Commune de Mbouda 25 919 600 000 10 TOTAL 57 1 937 410 004 Département du Haut Nkam 8 Services Déconcentrés 4 81 000 000 13 9 Commune de Bafang 7 236 000 000 13 10 Commune de Bakou 11 146 250 000 14 11 Commune de Bana 6 172 592 696 15 12 Commune de Bandja 14 294 370 000 16 13 Commune de Banka 14 409 710 012 17 14 Commune de Banwa 10 155 249 999 19 15 Commune de Kékem 5 152 069 520 20 TOTAL 71 1 647 242 227 Département des Hauts Plateaux 16 Services déconcentrés départementaux 1 10 000 000 21 17 Commune de Baham 11 195 550 000 21 18 Commune de Bamendjou 12 367 102 880 22 19 Commune de Bangou 20 371 710 000 24 20 Commune de Batié 6 146 050 002 26 TOTAL 50 1 090 412 882 Département du Koung Khi 21 Services Déconcentrés 2 122 000 000 27 22 Commune de Bayangam 6 257 710 000 27 23 Commune de Dembeng 5 180 157 780 28 24 Commune de Pete Bandjoun 12 287 365 000 28 TOTAL 25 847 232 780 Département de la Menoua 25 -

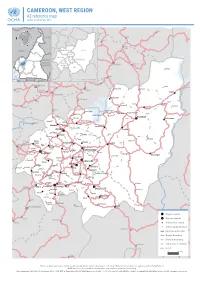

CAMEROON, WEST REGION A3 Reference Map Update of September 2018

CAMEROON, WEST REGION A3 reference map Update of September 2018 Nwa Ndu Benakuma CHAD WUM Nkor Tatum NIGERIA BAMBOUTOS NOUN FUNDONGMIFI MENOUA Elak NKOUNG-KHI CENTRAL H.-P. Njinikom AFRICAN HAUT- KUMBO Mbiame REPUBLIC -NKAM Belo NDÉ Manda Njikwa EQ. Bafut Jakiri GUINEA H.-P. : HAUTS--PLATEAUX GABON CONGO MBENGWI Babessi Nkwen Koula Koutoukpi Mabouo NDOP Andek Mankon Magba BAMENDA Bangourain Balikumbat Bali Foyet Manki II Bangambi Mahoua Batibo Santa Njimom Menfoung Koumengba Koupa Matapit Bamenyam Kouhouat Ngon Njitapon Kourom Kombou FOUMBAN Mévobo Malantouen Balepo Bamendjing Wabane Bagam Babadjou Galim Bati Bafemgha Kouoptamo Bamesso MBOUDA Koutaba Nzindong Batcham Banefo Bangang Bapi Matoufa Alou Fongo- Mancha Baleng -Tongo Bamougoum Foumbot FONTEM Bafou Nkong- Fongo- -Zem -Ndeng Penka- Bansoa BAFOUSSAM -Michel DSCHANG Momo Fotetsa Malânden Tessé Fossang Massangam Batchoum Bamendjou Fondonéra Fokoué BANDJOUN BAHAM Fombap Fomopéa Demdeng Singam Ngwatta Mokot Batié Bayangam Santchou Balé Fondanti Bandja Bangang Fokam Bamengui Mboébo Bangou Ndounko Baboate Balambo Balembo Banka Bamena Maloung Bana Melong Kekem Bapoungué BAFANG BANGANGTÉ Bankondji Batcha Mayakoue Banwa Bakou Bakong Fondjanti Bassamba Komako Koba Bazou Baré Boutcha- Fopwanga Bandounga -Fongam Magna NKONGSAMBA Ndobian Tonga Deuk Region capital Ebone Division capital Nkondjock Manjo Subdivision capital Other populated place Ndikiniméki InternationalBAF borderIA Region boundary DivisionKiiki boundary Nitoukou Subdivision boundary Road Ombessa Bokito Yingui The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. NOTE: In places, the subdivision boundaries may suffer of significant inacurracy. Date of update: 23/09/2018 ● Sources: NGA, OSM, WFP ● Projection: WGS84 Web Mercator ● Scale: 1 / 650 000 (on A3) ● Availlable online on www.humanitarianresponse.info ● www.ocha.un.org. -

Bamileke Businessmen in the Realm of Political Transition in Bamileke Region of Cameroon, 1990- 2000

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) |Volume III, Issue II, February 2019|ISSN 2454-6186 Bamileke Businessmen in the Realm of Political Transition in Bamileke Region of Cameroon, 1990- 2000 Nzeucheu Pascal1, Prof. Simon Tata Ngenge2 1History Department, Faculty of Arts, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon 2Vice Dean, Faculty of Law and Political Science, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon Abstract:-In the Bamilike County of Cameroon the businessmen the party in power, CPDM or for the newly created parties prior to the 1990s were not interested in party politics. After andto obtain representative positions.2 In this perspective, independence they were not interested in politics and business and politic became inseparable. Hence, how the concentrated in building wealth. The creation of a monolithic political transition occurred in the Bamileke area? What were systemon 1st September 1966, made it that they were simple the professional and political identifications of the Bamileke militants of the political system and went about doing their businesses successfully. The re-emergence of multi-party Businessmen that stepped in politics during this period? How democracy in 1990 changed the perception of the businessmen and why businessmen participated in local electoral toward political participation. To protect their businesses most of competitions? Finally what was the impact of this them became militants of Cameroon Democratic Movement participation on the reconfiguration of the Bamileke society? (CPDM) in their various home towns in order to preserve their These are some issues raised in the course of this paper. businesses while other defected from CPDM to join the opposition or created their own political parties. -

Plaquette-MC2.Pdf

BP. : 11 646 Yaoundé - Cameroun Tél. : (237) 222 20 07 67 Fax : (237) 233 01 45 81 E-mail : [email protected] Site web : www.adaf-amc2.org 1- MC² de Pitoa 5- MC² de Nyong et Foumou 2- MC² de Fontsa-Toula 6- MC² de Wum 3- MC² de Bangam 7- MC² de Nkolmetet 4- MC² de Kyé-ossi 8- MC² de Boumnyebel 2 Liste des MC et CDR opérationnelles au Cameroun au 31 octobre 2015 1 MC² de BAHAM 28 MC² de KRIBI CAMPO 55 MC² de SANTA 82 MC² de BANSOA 2 MC² de MANJO 29 MC² de LOUM 56 MC² de BAMENA 83 MC² de BAZOU 3 MC² de MELONG 30 MC² d’ESSE_AWAE II 57 MC² de LOLODORF 84 MC² de F4 4 MC² de PENKA MICHEL 31 MC² d’EKONDO TITI 58 MC² de BAHOUAN 85 MC² de BAMENKUMBO 5 MC² de BANDJOUN 32 MC² de KEKEM 59 MC² de NGAOUNDERE 86 MC² de MBANGASSINA 6 MC² de BADJOUMA 33 MC² de BATOURI 60 MC² de NKONGSAMBA 87 MC² de MENGUEME 7 MC² de BAFIA 34 MC² de MAMFE 61 MC² de NGUELEMENDOUKA 88 MC² de NGOMEZAP 8 MC² de BAMENDJOU 35 MC² de BALEVENG 62 MC² de DEMDENG 89 MC² de MEYOMESSALA 9 MC² de BANGOU 36 MC² de BAFANG RURALE 63 MC² de BELABO 90 MC² de DOKAYO 10 MC² de TPD 37 MC² de MAKENENE 64 MC² de FOKOUE 91 MC² d’OKOLA 11 MC² de BABOUANTOU 38 MC² de FOREKE - DSCHANG 65 MC² d’ESEKA 92 MC² de TONGO GANDIMA -

Outline Management Plan for Prunus Africana Bark, Cameroon

GCP/RAF/408/EC « MOBILISATION ET RENFORCEMENT DES CAPACITES DES PETITES ET MOYENNES ENTREPRISES IMPLIQUEES DANS LES FILIERES DES PRODUITS FORESTIERS NON LIGNEUX EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE » National Prunus africana Management Plan Cameroon CIFOR Verina Ingram, Abdon Awono, Jolien Schure, Nouhou Ndam June 2009 Avec l’appui financier de la Commission Européenne Table of Contents 1 Sommaire Exécutif ................................................................................................... 4 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 7 3 Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... 9 4 Objective ............................................................................................................... 10 4.1 Approach and methodology ............................................................................... 10 5 Context ................................................................................................................. 12 5.1 Policy background ............................................................................................ 12 5.1.1 International Standards .............................................................................. 15 5.2 Legal context ................................................................................................... 16 5.3 Trade ............................................................................................................. -

Restoration of Soil Fertility Through Agroforestry Technologies and Innovations News “The Project Has Had Great Impact in the People’S Lives” Scott B

Restoration of soil fertility through agroforestry technologies and innovations News “The project has had great impact in the people’s lives” Scott B. Ticknor, Political and Economic Section Chief, U.S. Embassy Yaounde cott was speaking recently in Bamenda after a visit to the Agricultural and Tree Products Pro - gramme (Food for Progress 2006) being exe - Scuted on North West and West regions of Cameroon by ICRAF and partners. The visit that ran from 11th through 15th May 2010 took Scott and Catherine Akom, (in charge of special projects including Food for Progress project) to some selected execution sites in the North West region. The visit was an op - portunity for the U.S. Embassy officials to behold, feel and touch the realities in the execution of the project. In an interview at the end of the visit, Scott told the project communication officer that he CANADEL has help promote agroforestry activities believes “it has been positive and the project has had and reduced poverty amongst farmers in the local - great impact in the people’s lives”. Scott also ity. Besides tree domestication, Madame Anjeh believes “the project is making a difference in the Marie, coordinator of PROWISDEV said the group region”. He was impressed “to see the commitment has equally benefitted from capacity building in the people have to their communities and to other domains such as seed and plantain multipli - improving their lives”. Scott was pleased with what cation, composting, mushroom cultivation, solanum he saw and thinks “this is good investment” for his potato seed multiplication, planting of leguminous government to needy communities in Cameroon. -

DECRET N° 95/082 DU 24 AVRIL 1995 Portant Création De Communes Rurales

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN PAIX-TRAVAIL-PATRIE DECRET N° 95/082 DU 24 AVRIL 1995 Portant création de communes rurales LE PRESIDENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE, Vu la constitution; Vu la loi n° 74/23 du 5 décembre 1974 portant organisation communale; Vu la loi n° 78/015 du 15 Juillet 1978 portant création des communautés urbaines; Vu le décret n° 72/349 du 14 Juillet 1972 portant organisation administrative de la République du Cameroun et ses textes modificatifs subséquents; Vu le décret 77/203 du 29 juin 1977 déterminant les communes et leur ressort territorial; Vu les décrets n°92/187 du ler septembre 1992 et n°92/206 du 5 octobre 1992 portant création des arrondissements et districts et leurs textes modificatifs subséquents; Vu les décrets n° 92/127 du 26 Août 1992 et n° 93/321 du 25 Novembre 1993 portant création des communes urbaines et rurales; Vu le décret n° 92/207 du 5 octobre 1992 portant création des nouveaux départements; Vu le décret 94/010 du 12 janvier 1994 fixant le ressort territorial de certaines unités administratives. DECRETE: Article Premier: — Sont créées à compter de la date de signature du présent décret les communes rurales ci-après: PROVINCE DE L'ADAMAOUA Département du Mbéré Commune rurale de ngaoui, dont le siège est à Ngaoui. Le ressort territorial de la commune rurale de Ngaoui couvre celui du district de Ngaoui. Le ressort territorial de la commune rurale de Djohong est modifié en conséquence. PROVINCE DU CENTRE Département de la Lékié — Commune rurale de Batchenga, dont le siège est à Batchenga.