The Anxiety of Confluence: Theory in and with Creative Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programme Final

RBS Schools Events All the best in children’s literature August 2006 www.edbookfest.co.uk Our thanks to Sponsors & Supporters Sponsor of the Schools Programme Welcome to the 2006 Edinburgh International Book Festival Schools Programme. This six-day programme is packed with the best in children’s writing for primary and secondary pupils plus a Schools Gala Day created especially for primary classes. As always, we have put together a first-class programme of authors, from perennial favourites to rising talent, as well as fantastic interactive events and workshops. This year’s Scottish contingent includes Catherine MacPhail, Julia Donaldson and Keith Gray. New to the programme are Steve Voake, John Boyne, Michelle Paver and Heather Dyer. An outstanding line-up for teenagers includes Graham Marks, Malorie Blackman, Bernard Ashley and Susan Price. For younger pupils, we bring you, amongst others, Simon James and SF ‘the Cat Man’ Said who will be back with more tales of mystical feline adventures. We are committed to enabling children to engage in the wonderful world of books in many different ways with the focus firmly on participation, imagination and creation. All this takes place in a specially created and young person-friendly tented village at Charlotte Square Gardens. You will notice that our schools events and bus fund are made possible by the kind support of The Royal Bank of RBS is committed to the education and development of the next generation Scotland. We are delighted to welcome them on board as sponsors of our Children’s and Schools Programmes. and we are proud to be associated with one of Edinburgh’s most prestigious festivals. -

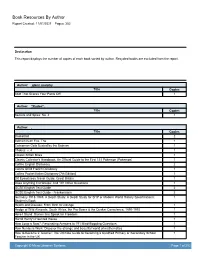

Book Resources by Author Report Created: 11/01/2021 Pages: 252

Book Resources By Author Report Created: 11/01/2021 Pages: 252 Declaration This report displays the number of copies of each book sorted by author. Recycled books are excluded from the report. Author: glenn murphy Title Copies Stuff That Scares Your Pants Off! 1 Author: "Kudos", Title Copies Secrets and Spies: No. 2 1 Author: , Title Copies Basketball 2 Batman is on Fire, The 1 Catwoman Gets Busted by the Batman 1 Chobits: v. 4 1 Classic british bikes 1 Classic Collector's Handbook: An Official Guide to the First 151 Pokemon (Pokemon) 1 Collins English Dictionary 2 Collins GEM French Dictionary 1 Collins Pocket Italian Dictionary [7th Edition] 1 DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Great Britain 1 Does Anything Eat Wasps: And 101 Other Questions 1 GCSE English Text Guide 2 GCSE English Text Guide - Frankenstein 2 Germany 1918-1945: A Depth Study: A Depth Study for SHP or Modern World History Specifications: 1 Student's Book Health and Disease: From Birth to Old Age 1 Hedge of Wild Almonds: South Africa, the Pro-Boers & the Quaker Conscience, 1890-1910 1 Here I Stand: Stories that Speak for Freedom 1 Horrid Henry's Haunted House 1 How Long is Now?: Fascinating Answers to 191 Mind-Boggling Questions 1 How Numbers Work: Discover the strange and beautiful world of mathematics 1 How to Become a Teacher: The Ultimate Guide to Becoming a Qualified Primary or Secondary School 1 Teacher in the UK Page 1 of 252 Copyright © Micro Librarian Systems Page 1 of 252 Human Body, The 1 If I Ran The Horse Show 1 Just Joking: 300 Hilarious Jokes, Tricky Tongue Twisters, -

Walker Books Seasonal Catalogue • May – August 2012 Lead Title Hero on a Bicycle by Shirley Hughes

Walker Books Seasonal Catalogue • May – August 2012 Lead Title Hero on a Bicycle By Shirley Hughes A gripping and moving first novel by one of the world’s best-loved writers for children. In extraordinary circumstances, people are capable of extraordinary things . It is 1944 and Florence is occupied by Nazi German forces. The Italian resistance movement has not given up hope, though – and neither have Paolo and his sister, Constanza. Both are desperate to fight the occupation, but what can two siblings do against a whole army with only a bicycle to help them? “A thrilling and moving tale, set in a wonderfully tendered background of war-torn Italy. Danger abounds, but so do love and courage. I enjoyed it enormously.“ Philip Pullman • A beautiful jacketed edition • Visit www.heroonabicycle.co.uk for historical details about the Second World War in Italy, including period photographs, videos and music, as well as interviews with Shirley Hughes, extra illustrations and much more • Shirley Hughes has won the Kate Greenaway Medal twice and has been awarded the OBE for her distinguished service to children’s literature. In 2007, Dogger was voted the UK’s favourite Kate Greenaway Medal-winning book of all time. • Please contact your area sales manager for your proof copy 9781406336108 • £9.99 • Hardback with jacket 198 x 129 mm • 224 pages • 10 years + 9781406340907 • £9.99 inc. VAT • Ebook Picture Books The Duckling Gets a cookie!? By Mo Willems The very latest Pigeon title from the award-winning, best-selling Mo Willems – laugh out loud fun for all the family! He has whined, wheedled, fibbed and hollered his way through many books. -

Stratford Literary Festival

Stratford-upon-Avon Literary Festival Jacqueline Wilson Alastair Campbell Paul Merton Simon Russell Beale Harriet Walter Nick Butterworth Hugo Rifkind Antonia Fraser Christina Lamb Alexander McCall Smith Chris Riddell Richard Davenport Hines Helen Lederer Jessie Burton Douglas Hurd David & Ben Crystal and many more… Box Office: 01789 207100 or online at: www.stratfordartshouse.co.uk The Stratford-upon-Avon Literary Festival 25th April to 3rd May 2015 www.stratlitfest.co.uk PLUS: Writing Competition | Song for Stratford | Book Group MACDONALD ALVESTON MANOR HOTEL ONE OF THE FINEST 4-STAR HOTELS IN WARWICKSHIRE, OFFERING GREAT LUXURY ACCOMMODATION IN ONE OF THE MOST BEAUTIFUL AND HISTORIC PARTS OF ENGLAND. • Set in its own grounds just 5 minutes walk from • Our Vital Health & Wellbeing club all the cultural attractions of Stratford-upon-Avon provides you with an equal balance • Perfect venue for leisure breaks, romantic of luxury and tranquility weekends, business meetings, weddings and • Savor specialty dishes and fine wines in special occasions our award-winning Manor Restaurant For more information or to book call 0844 879 9138 or email [email protected] Macdonald Alveston Manor Hotel, Clopton Bridge, Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, CV37 7HP WWW.MACDONALDHOTELS.CO.UK/ALVESTONMANOR 22141_Alveston A5 Advert AW.indd 1 03/02/2014 09:09 Box Office: 01789 207100 3 MACDONALD or online at www.stratfordartshouse.co.uk | www.stratfordliteraryfestival.co.uk ALVESTON MANOR HOTEL Welcome to the 2015 Festival he theme of this year’s Festival is My Voice – one that resonates through all the events Tin our programme We bring you a wonderfully varied selection this year, which we hope includes something for everyone to enjoy. -

Day: a Study of the Presentation of Bereavement in Novels For

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk University of Southampton FACULTY OF ENGLISH (Creative Writing) School of Humanities Day A Study of the Presentation of Bereavement in Novels for Secondary Level Children by Alistair Schofield Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2011 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ENGLISH (CREATIVE WRITING) SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Doctor of Philosophy DAY By Alistair Schofield This thesis comprises critical reflection and novel. Claims for originality in the novel lie in the combination of the specific geographical location of Leeds, the 1970s setting, the narrative time frame of twenty‐four hours, and the use of the mundane not as a setting from which to escape but as one in which epiphanous moments can be found. These key decisions were made early in the evolution of the novel and are discussed, along with other issues such teenage sexuality, in the first section of the critical reflection. -

Chatterbooks Themed Book List Illustrations

Chatterbooks themed book list Illustrations Reading & activity ideas for your Chatterbooks group IDEA Celebrating a world of stories with our Illustrations themed book list! Here are some recent books from our Children’s Reading Partners publisher partners, showing a range of inspiring approaches to illustration – in picture books, and also in illustrated fiction and non-fiction. This is a lovely selection of books including highly-illustrated picture books, children’s fiction and non-fiction; books about exploring and reading pictures and creating your own illustrations; and books about famous artists. You’ll also find activities and discussion ideas linked to the featured titles – plus more reading ideas and a list of some classic picture books. Children’s Reading Partners is a national partnership of children’s publishers and libraries working together to bring reading promotions and author events to as many children and young people as possible. Books about reading pictures and creating your own illustrations Frida and Bear Anthony Browne & Hanne Bartholin Walker 978-1406365573 Frida and Bear both love to draw – but what? First Frida draws a shape, then Bear turns it into a picture. Then Bear draws a shape for Frida as the shape game begins again. Celebrate the power of the imagination with this picture book which inspires creativity, inviting the reader to play the shape game too. Anthony Browne is an author-illustrator. He was Children’s Laureate from 2009 to 2011 has won many awards including the CILIP Kate Greenaway Medal and the Hans Christian Andersen Award. He lives in Canterbury, Kent. Hanne Bartholin is a Danish illustrator.