Misinformed and Other Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing for Productivity in the Hospitality Industry © Robert Christie Mill

Managing for Productivity in the Hospitality Industry © Robert Christie Mill This work is licensed under a Creative Commons-ShareAlike 4.0 International License Contents About the author ............................................................................................................1 Robert Christie Mill ..................................................................................................................1 Preface .............................................................................................................................2 Why should we be concerned about productivity and what can we do about it?............2 How do we hire productive employees? ...............................................................................3 How can workplaces and jobs be designed to maximize employee productivity? .........3 How can employees be motivated to be productive? ..........................................................4 Chapter 1 Defining productivity ...................................................................................7 1.1 The challenges of productivity ..........................................................................................7 Impact on the hospitality industry .................................................................................7 Life cycle of the hospitality industry ..............................................................................7 Nature of the industry .....................................................................................................8 -

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos Santana on New 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection Featuring Five Limited-Edition Signature and Replica Guitars Exclusive Guitar Collection Developed in Partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender®, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars to Benefit Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Centre Antigua Limited Quantities of the Crossroads Guitar Collection On-Sale in North America Exclusively at Guitar Center Starting August 20 Westlake Village, CA (August 21, 2019) – Guitar Center, the world’s largest musical instrument retailer, in partnership with Eric Clapton, proudly announces the launch of the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection. This collection includes five limited-edition meticulously crafted recreations and signature guitars – three from Eric Clapton’s legendary career and one apiece from fellow guitarists John Mayer and Carlos Santana. These guitars will be sold in North America exclusively at Guitar Center locations and online via GuitarCenter.com beginning August 20. The collection launch coincides with the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Festival in Dallas, TX, taking place Friday, September 20, and Saturday, September 21. Guitar Center is a key sponsor of the event and will have a strong presence on-site, including a Guitar Center Village where the limited-edition guitars will be displayed. All guitars in the one-of-a-kind collection were developed by Guitar Center in partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars, drawing inspiration from the guitars used by Clapton, Mayer and Santana at pivotal points throughout their iconic careers. The collection includes the following models: Fender Custom Shop Eric Clapton Blind Faith Telecaster built by Master Builder Todd Krause; Gibson Custom Eric Clapton 1964 Firebird 1; Martin 000-42EC Crossroads Ziricote; Martin 00-42SC John Mayer Crossroads; and PRS Private Stock Carlos Santana Crossroads. -

PATHWAYS INTO POVERTY Lived Experiences Among LGBTQ People

RESEARCH THAT MATTERS PATHWAYS INTO POVERTY Lived Experiences Among LGBTQ People September 2020 Bianca D.M. Wilson Alexandra-Grissell H. Gomez Madin Sadat Soon Kyu Choi M. V. Lee Badgett Pathways into Poverty: Lived Experiences Among LGBTQ People | 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY More than a decade of empirical research has shown that LGBT people in the United States experience poverty at higher rates compared to cisgender heterosexual people.1 More recently, research has also shown that transgender people and cisgender bisexual women experience the highest rates of economic insecurity.2 In response to this knowledge, numerous advocacy and direct services organizations have worked to identify public policies and interventions that can address the high rates of poverty among sexual and gender minority people. However, there is very little research to support any claims about why poverty is so prevalent among LGBT people. Without greater specification of the causes of poverty and the factors affecting the experience of poverty, policies and services may be using less effective mechanisms for alleviating economic insecurity. In the interest of informing the ongoing dialogue about how sexual orientation and gender identity relate to poverty, we designed this study to document experiences with poverty, including factors leading to and maintaining economic insecurity among LGBTQ people. This report is one of several that will be developed from the data collected in the Pathways to Justice Project. The Pathways Project aimed to document updated figures on the national and state-by-state rates of LGBT poverty and explore the experiences and needs of LGBTQ adults living in poverty. As part of this project, we conducted in-person interviews with 93 LGBTQ people in Los Angeles County (n = 60) and Kern County (n = 33) with low incomes or other indicators of economic instability. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

'Zombie' Homes by Jim Redden January 4, 2018 Mayor Says Cost, Complexity Force Other Solutions but Might Consider More Reforms to Program Pushed by Predecessor

The Portland Tribune Wheeler Pauses Hales Campaign to Foreclose on 'Zombie' Homes By Jim Redden January 4, 2018 Mayor says cost, complexity force other solutions but might consider more reforms to program pushed by predecessor. Portland used the threat of foreclosure to force scofflaw landlords to take responsibility for 10 derelict properties over the past 18 months. But the City Council did not approve any others for foreclosure in all of 2017, despite pledging to routinely review potential new ones. The reversal happened after former Mayor Charlie Hales — who pushed the council to crack down harder on "zombie" homes — left office. His successor, Mayor Ted Wheeler, doesn't consider foreclosures a high priority. "The obstacles for government to take away someone's property are formidable," says Wheeler, who took office last January. "It's a very expensive, multiyear process. I'm not sure that's the best use of our resources." The change essentially leaves the enforcement system where it was before the council approved Hales' June 2016 reforms aimed at cracking down on zombie homes, which often sit empty and are a blight on neighborhoods. The Bureau of Development Services, which inspects and cites substandard properties for code violations, maintains a list of hundreds of the worst properties in the city. When BDS cannot convince landlords to pay their fines and fix them up, it can refer them to the City Auditor's Office, which tries again. When the auditor runs out of options, properties can be referred to the council to be approved for foreclosure. If the council agrees, the property is sent to the city treasurer, who schedules a foreclosure auction. -

Download (4MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] 6iThe Adaptation of Literature to the Musical Stage: The Best of the Golden Age” b y Lee Ann Bratten M. Phil, by Research University of Glasgow Department of English Literature Supervisor: Mr. AE Yearling Ju ly 1997 ProQuest Number: 10646793 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uesL ProQuest 10646793 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. -

Squeeze Plays

The Squeeze Play By James R. Klein **** The most fascinating of all advanced plays in bridge is undoubtedly the squeeze play. Since the origin of bridge, the ability to execute the squeeze play has been one of the many distinguishing marks of the expert player. What is more important is the expert's ability to recognize that a squeeze exists and therefore make all the necessary steps to prepare for it. Often during the course of play the beginner as well as the advanced player has executed a squeeze merely because it was automatic. The play of a long suit with defender holding all the essential cards will accomplish this. The purpose of the squeeze play is quite simple. It is to create an extra winner with a card lower than the defender holds by compelling the latter to discard it to protect a vital card in another suit. While the execution of the squeeze play at times may seem complex, the average player may learn a great deal by studying certain principles that are governed by it. 1. It is important to determine which of the defenders holds the vital cards. This may be accomplished in many ways; for example, by adverse bidding, by a revealing opening lead, by discards and signals but most often by the actual fall of the cards. This is particularly true when one of the defenders fails to follow suit on the first or second trick. 2. It is important after the opening lead is made to count the sure tricks before playing to the first trick. -

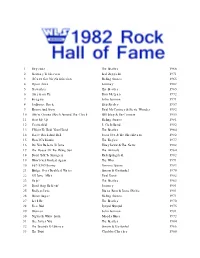

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Ar

1 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 2 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Arms Journey 1982 5 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 6 American Pie Don McLean 1972 7 Imagine John Lennon 1971 8 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 9 Ebony And Ivory Paul McCartney & Stevie Wonder 1982 10 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 11 Start Me Up Rolling Stones 1981 12 Centerfold J. Geils Band 1982 13 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 14 I Love Rock And Roll Joan Jett & The Blackhearts 1982 15 Hotel California The Eagles 1977 16 Do You Believe In Love Huey Lewis & The News 1982 17 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 18 Don't Talk To Strangers Rick Springfield 1982 19 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 20 867-5309/Jenny Tommy Tutone 1982 21 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel 1970 22 '65 Love Affair Paul Davis 1982 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 Don't Stop Believin' Journey 1981 25 Endless Love Diana Ross & Lionel Richie 1981 26 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 27 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 28 Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd 1975 29 Woman John Lennon 1981 30 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 31 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 32 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 33 The Twist Chubby Checker 1960 34 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 35 Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield 1981 36 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 37 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 38 California Dreamin' The Mamas & The Papas 1966 39 Lola The Kinks 1970 40 Lights Journey 1978 41 Proud -

January 14 & 15, 2020 Gateway Civic Center Oberlin, KS

January 14 & 15, 2020 Gateway Civic Center Oberlin, KS 2020 Proceedings, Vol. 17 Table of Contents Session Summaries............................................................................................................................... ii Presenters. ........................................................................................................................................... iii Gateway Conference Center Floor Plan. ........................................................................................ v Alternative Crops—What We Know, Don’t Know and Should Think About. .................... 1 Lucas Haag, Northwest Regional Agronomist, K-State NW Research-Extension Center Colby, Kansas Beyond Grain: The Value of Wheat in the Production Chain .................................................. 6 Aaron Harries, Vice President of Research and Operations, Kansas Wheat, Manhattan, Kansas Cover Crops as a Weed Management Tool ................................................................................. 12 Luke Chism and Malynda O’Day, Graduate Students, K-State Dept. of Agronomy, Manhattan, Kansas Current Financial Status of NW Kansas Farms ......................................................................... 19 Jordan Steele, Executive Extension Agricultural Economist, NW Farm Management, Colby, Kansas Mark Wood, Extension Agricultural Economist, NW Farm Management, Colby, Kansas Insect Management in Dryland Corn ............................................................................................ 25 Sarah -

The-Encyclopedia-Of-Cardplay-Techniques-Guy-Levé.Pdf

© 2007 Guy Levé. All rights reserved. It is illegal to reproduce any portion of this mate- rial, except by special arrangement with the publisher. Reproduction of this material without authorization, by any duplication process whatsoever, is a violation of copyright. Master Point Press 331 Douglas Ave. Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5M 1H2 (416) 781-0351 Website: http://www.masterpointpress.com http://www.masteringbridge.com http://www.ebooksbridge.com http://www.bridgeblogging.com Email: [email protected] Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Levé, Guy The encyclopedia of card play techniques at bridge / Guy Levé. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-55494-141-4 1. Contract bridge--Encyclopedias. I. Title. GV1282.22.L49 2007 795.41'5303 C2007-901628-6 Editor Ray Lee Interior format and copy editing Suzanne Hocking Cover and interior design Olena S. Sullivan/New Mediatrix Printed in Canada by Webcom Ltd. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 11 10 09 08 07 Preface Guy Levé, an experienced player from Montpellier in southern France, has a passion for bridge, particularly for the play of the cards. For many years he has been planning to assemble an in-depth study of all known card play techniques and their classification. The only thing he lacked was time for the project; now, having recently retired, he has accom- plished his ambitious task. It has been my privilege to follow its progress and watch the book take shape. A book such as this should not to be put into a beginner’s hands, but it should become a well-thumbed reference source for all players who want to improve their game. -

032019.Log ********** 88.5 Fm Keom 03/20/19

032019.LOG ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 03/20/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 12:00 A 74 Boogie On Reggae Woman Stevie Wonder 12:04 A 75 The Way I Want To Touch You Captain & Tennille 12:06 A 70 We've Only Just Begun Carpenters 12:09 A 82 Rock The Casbah Clash 12:16 A 76 Somebody To Love Queen 12:21 A 78 Beast Of Burden Rolling Stones 12:25 A 83 It's Raining Men Weather Girls 12:30 A 72 The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face Roberta Flack 12:31 A Tom's Diner Suzanne Vega 12:35 A Typical Male Tina Turner 12:39 A 93 Again Janet Jackson 12:42 A 75 Fox On The Run Sweet 12:46 A 74 Do It ('Til You're Satisfied) B.T. Express 12:53 A 75 Shining Star Earth, Wind & Fire ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 03/20/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 01:00 A 74 Can't Get Enough Bad Company 01:04 A 75 Island Girl Elton John 01:07 A 81 Slow Hand Pointer Sisters 01:11 A 67 Judy In Disguise (With Glasses) John Fred 01:16 A 77 You And Me Alice Cooper Page 1 032019.LOG 01:21 A 80 Fool In The Rain Led Zepplin 01:23 A 73 Hocus Pocus Focus 01:27 A 78 Hot Child In The city Nick Gilder 01:30 A 98 My Favorite Mistake Sheryl Crow 01:31 A 85 Saving All My Love For You Whitney Houston 01:35 A 72 Run Run Run Jo Jo Gunne 01:37 A Cradle Of Love Billy Idol 01:41 A 75 My Little Town Simon & Garfunkel 01:46 A 75 Wildfire Michael Murphey 01:49 A 77 Lucille Kenny Rogers ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 03/20/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 02:01 A 80 Funkytown Lipps, Inc. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat.