An Archaeological Resource Assessment of Post-Medieval Leicestershire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OLDER PERSONS BOOKLET 2011AW.Indd

Older Persons’ Community Information Leicestershire and Rutland 2011/2012 Friendship Dignity Choice Independence Wellbeing Value Events planned in Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland in 2011. Recognition Directory of Information and Services for Older People. Leicestershire County and Rutland Thank you With thanks to all partner organisations involved in making September Older Persons’ Month 2011 a success: NHS Leicestershire County and Rutland – particularly for the major funding of the printing of this booklet Communities in Partnership (CiP) – for co-ordinating the project Leicestershire County Council – for co-funding the project Age Concern Leicester Shire and Rutland – particularly for acting as the host for the launch in Leicester NHS Leicester City and Leicester City Council - for close partnership working University Hospitals of Leicester Rutland County Council Blaby District Council Melton Borough Council Charnwood Borough Council North West Leicestershire District Council Harborough District Council Hinckley and Bosworth Borough Council Oadby and Wigston Borough Council Voluntary Actions in Blaby, Charnwood, North-West Leics, South Leicestershire, Hinckley and Bosworth, Melton, Oadby and Wigston and Rutland The Older People’s Engagement Network (OPEN) The Co-operative Group (Membership) The following for their generous support: Kibworth Harcourt Parish Council, Ashby Woulds Parish Council, Fleckney Parish Council, NHS Retirement Fellowship With special thanks to those who worked on the planning committee and the launch sub-group. -

A Short Description of the Original Building Accounts of Kikby Muxloe Castle, Leicestershire

ORIGINAL BUILDING ACCOUNTS OF KIRBY MUXLOE OASTLE. 87 A SHORT DESCRIPTION OF THE ORIGINAL BUILDING ACCOUNTS OF KIKBY MUXLOE CASTLE, LEICESTERSHIRE, RECENTLY DISCOVEBED AT THE MANOR HOUSE, ASHBYDELAZoUOH. BY THOS. H. FOBBROOKE, F.S.A. The Manuscripts and other Documents belonging to the ancient family of Hastings, of AshbydelaZouch, are amongst the finest and most interesting in the kingdom. After the destruction of their ancient castle at Ashby, these papers were stored at Donington Hall, but since the recent sale of that estate have been housed at the Manor House at Ashby delaZouch, where through the kindness of Lady Maud Hastings, they were exhibited to, and much admired by, the members of the Leicestershire Archaeological Society, on the occasion of their annual excursion last year. One of the most interesting of these MSS. is a XV. century book of building accounts, relating to the erection of Kirby Castle by William Lord Hastings, between the years 1480 and 1484. This book was first shewn to me when I was measuring the ruined castle at Ashby, the drawings of which were afterwards published by this Society in the Reports and Papers of the Asso ciated Societies' Publication, Vol. XXI., Part 1 (1911). On the discovery that the accounts related entirely to Kirby Castle, they were entrusted to my care through the kindness of Lady Maud Hastings, and I at once communicated with C. R. Peers, Esq., Secretary of the Society of Antiquaries, who at that time was engaged on the conservation of the old ruin at Kirby, under the Ancient Monuments Act. -

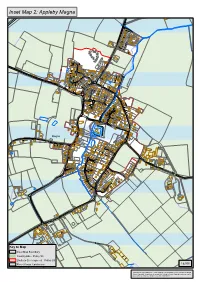

Inset Map 2: Appleby Magna

Inset Map 2: Appleby Magna Magna Key to Map Inset Map Boundary Countryside - Policy S3 Limits to Development - Policy S3 River Mease Catchment 1:6,000 Reproduction from Ordnance 1:1250 mapping with permission of the Controller of HMSO Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings Licence No: 100019329 Inset Map 3: Ashby de la Zouch Key to Map NWLDC Boundary Inset Map Boundary Countryside - Policy S2 Limits to Development - Policy S2 Housing Provision planning permissions - Policy H1 Housing Provision resolutions - Policy H2 Ec2(1) Housing Provision new allocations - Policy H3 Employment Provision Permissions - Policy Ec1 H3a Employment Allocations new allocations - Policy Ec2 Primary Employment Areas - Policy Ec3 EMA Safeguarded Area - Policy Ec5 Ec3 Leicester to Burton rail line - Policy IF5 River Mease Catchment H3a Ec2(1) National Forest - Policy En3 Sports Field H1b Ec3 H1a Ec3 Inset Map 4 Ec1a ASHBY-DE-LA-ZOUCH 1:9,000 Reproduction from Ordnance 1:1250 mapping with permission of the Controller of HMSO Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings Licence No: 100019329 Willesley W ill e s ley P ar k Inset Map 8: Castle Donington Trent Valley Washlands Ec3 CASTLE Inset Map 9 H1c Melbourne Paklands Key to Map Reproduction from Ordnance 1:1250 mapping with permission of the Controller of HMSO Crown Copyright. 1:11,000 Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead Inset Map Boundary -

Lyndale Cottage, 31 Worthington Lane, Newbold Coleorton, Leicestershire, LE67 8PJ

Lyndale Cottage, 31 Worthington Lane, Newbold Coleorton, Leicestershire, LE67 8PJ Lyndale Cottage, 31 Worthington Lane, Newbold Coleorton, Leicestershire, LE67 8PJ Guide Price: £400,000 Extending to approximately 2000 sqft, a substantial four/five bedroom period cottage dating back to 1750. The Cottage in this village setting boasts a large 26ft dual aspect living room with log burner, generous open plan living kitchen, separate utility, pantry and cloakroom together with study and vaulted conservatory. To the first floor there are five bedrooms including master with contemporary en-suite and a fully re-furbished family bathroom. Outside, cottage gardens and a detached outbuilding suitable for a workshop. Features • Substantial family cottage • Five bedrooms, two bathrooms • Large 26ft living room • Generous living kitchen and study • Cottage gardens • Potential workshop • Delightful village setting • Ideal for commuters Location The village boasts a local village pub, Primary School and excellent footpath links to the National Forest. Set approximately three miles east of Ashby town centre (a small market town offering a range of local facilities and amenities), Newbold Coleorton lies close to the A42 dual carriageway with excellent road links to both the M1 motorway corridor (with East Midland conurbations beyond) and west to Birmingham. The rolling hills of North West Leicestershire and the adjoining villages of Peggs Green, Coleorton, Worthington and Griffydam offer excellent countryside with National Forest Plantations linked by public footpaths, public houses and nearby amenities and facilities. Travelling Distances: Leicester - 16.2 miles Derby - 17.2 miles Ashby de la Zouch - 4.7miles East Midlands Airport - 6.3 miles Accommodation Details - Ground Floor side gardens. -

Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review

Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review September 2020 2 Contents Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review .......................................................... 1 August 2020 .............................................................................................................. 1 Role of this Evidence Base study .......................................................................... 6 Evidence Base Overview ................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 7 General Description of Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge........................... 7 Figure 1: Map showing the extent of the Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge 8 2. Policy background ....................................................................................... 9 Formulation of the Green Wedge ....................................................................... 9 Policy context .................................................................................................... 9 National Planning Policy Framework (2019) ...................................................... 9 Core Strategy (December 2009) ...................................................................... 10 Site Allocations and Development Management Policies Development Plan Document (2016) ............................................................................................. 10 Landscape Character Assessment (September 2017) .................................... -

Chairman's Update

LEICESTERSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL HIGHWAYS FORUM FOR NORTH WEST LEICESTERSHIRE 14TH JULY 2016 CHAIRMAN’S UPDATE REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR OF ENVIRONMENT AND TRANSPORT T5 Street Lighting Transformation Project 2016/17 1. Leicestershire Highways is upgrading the County Councils street lighting stock to LEDs, in order to make substantial savings in energy, carbon and maintenance costs. Leicestershire County Council will be carrying out over 68,000 street light replacements across the county and are programmed to complete all installations within the next 3 years. Initially we are concentrating on the low level street lights (5 & 6m columns) which are mainly in residential areas with the high level installations (6m & above) due to commence from October this year. 2. The first low level installations were successfully carried out in Shepshed, as programmed in March this year, before a full roll-out of four installation teams started work in Loughborough, Hugglescote and Whitwick throughout April and into May. The project is progressing well and is on programme both in time and budget. 3. Details of the full construction programme for the project are being prepared in a suitable format to share with Members and residents and we anticipate this information will be available by the end of June. 4. The table below provides the implementation programme to the end of the current financial year. 2016 May Whitwick, Loughborough, Coalville June Coalville cont., Oadby & Wigston July Ravenstone, Packington, Coleorton, Ellistown, Swannington, Ibstock, Anstey, -

The White House Zion Hill Coleorton LE67 8JP

The White House Zion Hill Coleorton LE67 8JP £675,000 A DELIGHTFUL COUNTRY COTTAGE of charm & character with a STYLISH MODERN INTERIOR, occupying a wonderful mature plot with a SWEEPING GRAVEL DRIVE, spacious versatile interior of over 2,500 sq ft, with 3 reception rooms, fitted kitchen, 5 DOUBLE BEDROOMS 3 bathrooms, double garage, LARGE GARDENS Property Features and quartz work surfaces with matching units within the utility room. Completing the ground floor is the versatile Country Cottage 5 DoubleBedrooms bedroom five, currently doubling as a home office with a Excellent Plot 3 Reception rooms large en-suite bathroom. On the first floor are a further four genuine double bedrooms including the master bedroom Versatile Interior 3 Bathrooms with built in wardrobes and en-suite shower room, the main family bathroom has also been re-fitted with a stylish Over 2,500 sq ft Bespoke Kitchen modern suite. Double garage Super Fast Broadband An impressive sweeping gravel driveway with electric gates off Clay Lane provides more than ample parking and access Full Description to the attached double garage. The mature and established lawned gardens wrap around the property, with a sunken sun terrace, ideally positioned for outdoor entertaining and within the grounds are the ruins of a stone building and a The White House is a delightful country cottage of charm & number of mature fruit trees. character which occupies an excellent private well screened plot on the corner of Zion Hill and Clay Lane. Dating back in Lying in a semi rural position within the sought after hamlet part to the 18th century, the property has been further of Peggs Green in the parish of Coleorton, which is a small extended and adapted, creating a versatile spacious interior village with 3 great pubs, village post office, Church and of over 2500 sq ft including the garage, which also offers village primary school, lying approximately four miles from huge potential to further extend & convert if required. -

The North West Leicestershire (Electoral Changes) Order 2014

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2014 No. 3060 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The North West Leicestershire (Electoral Changes) Order 2014 Made - - - - 5th November 2014 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Under section 58(4) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009( a) (“the Act”) the Local Government Boundary Commission for England( b) (“the Commission”) published a report dated February 2014 stating its recommendations for changes to the electoral arrangements for the district of North West Leicestershire. The Commission has decided to give effect to the recommendations. A draft of the instrument has been laid before Parliament and a period of forty days has expired and neither House has resolved that the instrument be not made. The Commission makes the following Order in exercise of the power conferred by section 59(1) of the Act: Citation and commencement 1. —(1) This Order may be cited as the North West Leicestershire (Electoral Changes) Order 2014. (2) This Order comes into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of councillors, on the day after it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2015. Interpretation 2. In this Order— “map” means the map marked “Map referred to in the North West Leicestershire (Electoral Changes) Order 2014”, prints of which are available for inspection at the principal office of the Local Government Boundary Commission for England; “ordinary day of election of councillors” has the meaning given by section 37 of the Representation of the People Act 1983( c). -

North West Leicestershire—Main Settlement Areas Please Read and Complete

North West Leicestershire—Main settlement areas Please read and complete North West Leicestershire District Council - Spatial Planning - Licence No.: 100019329 Reproduction from Ordnance Survey 1:1,250 mapping with permission of the Controller of HMSO Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. For further help and advice contact North West Leicestershire Housing Advice Team. Freephone: 0800 183 0357, or e-mail [email protected] or visit our offices at Whitwick Road, Coalville, Leicester LE67 3FJ. Tell us where you would prefer to live Please tick no more than THREE Main Areas you would prefer to live in, then just ONE Sub Area for each main area you select . Please note you will not be restricted to bidding for properties in only these areas Main Area Sub Area (Please select ONLY three) 9 (Please select ONLY one for each 9 main area you have ticked) Ashby–de-la-Zouch Town centre Marlborough Way Northfields area Pithiviers/Wilfred Place Willesley estate Westfields estate (Tick only one) Castle Donington Bosworth Road estate Moira Dale area Windmill estate Other (Tick only one) Coalville Town centre Agar Nook Avenue Road area Greenhill Linford & Verdon Crescent Meadow Lane/Sharpley Avenue Ravenstone Road area 2 (Tick only one) Ibstock Town centre Central Avenue area Church View area Deepdale area Leicester Road area (Tick only one) Kegworth Town centre Jeffares Close area Mill Lane estate Thomas Road estate (Tick only one) Measham Town centre -

Great Dalby Funding Agreement

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION REDACTION SHEET Great Dalby School Deed of Novation and Variation Exemptions in full n/a Partial exemptions Personal Information has been redacted from this document under Section 40 of the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act. Section 40 of the FOI Act concerns personal data within the meaning of the Data Protection Act 1998. Factors for disclosure Factors for Withholding . further to the understanding of . To comply with obligations and increase participation in under the Data Protection Act the public debate of issues concerning Academies. to ensure transparency in the accountability of public funds Reasons why public interest favours withholding information Whilst releasing the majority of the Great Dalby School Deed of Novation and Variation will further the public understanding of Academies, the whole of the Great Dalby School Deed of Novation and Variation cannot be revealed. If the personal information redacted was to be revealed under the FOI Act, Personal Data and Commercial interests would be prejudiced. DEED OF NOVATION AND VARIATION OF FUNDING AGREEMENT 3( ~ 2016 SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION AND GREAT DALBY SCHOOL AND BRADGATE EDUCATION PARTNERSHIP The Parties to this Deed are: (1) THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION of Sanctuary Buildings, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3BT (the "Secretary of State"); (2) GREAT DALBY SCHOOL, a charitable company incorporated In England and Wa les with registered company number 08391101 whose registered address Is at Top End, Great Dalby, Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire, LE14 2HA ("the Outgoing Party"); and (3) BRADGATE EDUCATION PARTNERSHIP, a charitable company incorporated in England and Wa les with registered company number 08168237 whose registered address Gaddesby Primary School, Ashby Road, Gaddesby, Leicester, Leciestshire, LE7 4WF (the "Incoming Party"), together referred to as the "Parties". -

Castle Studies Group Bibliography No. 23 2010 CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 23 (2010)

Castle Studies Group Bibliography No. 23 2010 CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 23 (2010) By John R. Kenyon Introduction This is advance notice that I plan to take the recent publications compilation to a quarter century and then call it a day, as I mentioned at the AGM in Taunton last April. So, two more issues after this one! After that, it may be that I will pass on details of major books and articles for a mention in the Journal or Bulletin, but I think that twenty-five issues is a good milestone to reach, and to draw this service to members to a close, or possibly hand on the reins, if there is anyone out there! No sooner had I sent the corrected proof of last year’s Bibliography to Peter Burton when a number of Irish items appeared in print. These included material in Archaeology Ireland, the visitors’ guide to castles in that country, and then the book on Dublin from Four Court Press, a collection of essays in honour of Howard Clarke, which includes an essay on Dublin Castle. At the same time, I noted that a book on medieval travel had a paper by David Kennett on Caister Castle and the transport of brick, and this in turn led me to a paper, published in 2005, that has gone into Part B, Alasdair Hawkyard’s important piece on Caister. Wayne Cocroft of English Heritage contacted me in July 2009, and I quote: - “I have just received the latest CSG Bibliography, which has prompted me to draw the EH internal report series to your attention. -

Heritage Appraisal

Parish of Burton & Dalby Neighbourhood Plan Heritage Appraisal David Edleston BA(Hons) Dip Arch RIBA IHBC Conservation Architect & Historic Built Environment Consultant Tel : 01603 721025 July 2019 Parish of Burton & Dalby Neighbourhood Plan : Heritage Appraisal July 2019 Contents 1.0 Introduction 1.1 The Parish of Burton & Dalby 1.2 Neighbourhood Plan 1.3 Heritage Appraisal : Purpose & Objectives 1.4 Methodology and Approach 2.0 Great Dalby 2.1 Historic Development 2.2 Great Dalby Conservation Area 2.3 Architectural Interest and Built Form 2.4 Traditional Building Materials and Details 2.5 Spatial Analysis : Streets, Open Spaces, Green Spaces and Trees 2.6 Key Views, Landmarks and Vistas 2.7 Setting of the Conservation Area 2.8 Character Areas : Townscape and Building Analysis 2.9 Summary of Special Interest 2.10 Other Heritage Assets 3.0 Burton Lazars 3.1 Historic Development 3.2 Architectural Interest and Built Form 3.3 Traditional Building Materials and Details 3.4 Key Views, Landmarks and Vistas 3.5 Setting 3.6 Summary of Defining Characteristics 2 Parish of Burton & Dalby Neighbourhood Plan : Heritage Appraisal July 2019 4.0 Little Dalby 4.1 Historic Development 4.2 Architectural Interest and Built Form 4.3 Traditional Building Materials and Details 4.4 Key Views, Landmarks and Vistas 4.5 Setting 4.6 Summary of Defining Characteristics 5.0 Conclusions 5.1 Summary of the Defining Characteristics for the Historic Built Environment Appendix A : Designated Heritage Assets Appendix B : Local List (Non-designated Heritage Assets) Appendix C : Relevant Definitions Appendix D : References Cover photographs 01 : Vine Farm & Pebble Yard, Top End, Great Dalby (top); 02 : Manor Farm, Little Dalby (bottom left); 03 : The Old Hall, Burton Lazars (bottom right) 3 Parish of Burton & Dalby Neighbourhood Plan : Heritage Appraisal July 2019 1.0 Introduction 1.1 The Parish of Burton & Dalby 1.1.1 The Parish of Burton and Dalby is within the Melton Borough of Leicestershire and lies to the south and east of Melton Mowbray.