9 Ghost-Writing for Wulatji: Incubation and Re-Dreaming As Song Revitalisation Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Se Non E Vero, E Molto Ben Trovato Issue 440 March 2020 $2

Se Non E Vero, E Molto Ben Trovato Issue 440 March 2020 $2 Community news for Wollombi, Laguna and surrounding districts 1 Issue 440 - Our Own News – March 2020 View from the Ridge Top - Is it 1929 all over again?! Monthly Rainfall in the Wollombi Valley Source: BoM Climate Data (2019), Ridgetop Consulting (2020) Monthly rainfall for the Wollombi Valley is highlighted above for years 1928, 1929, 2019 and 2020 (includes a 200mm conservative guesstimate for February 2020). Detailed analysis of rainfall ahead of three key bushfire periods was undertaken for 1929, 1993/4 and 2019/20. In all key fire events, there was very limited Spring rainfall followed by delayed Summer rains. In 1929, this late Summer rain arrived in a major rain event that began on 6th February. This was after the terrible bushfires of 1929 (reported in last month’s OON). In 1994 (not shown), the rains arrived in the January and a more reasonable amount in February. On average, the most rainfall arrives during Summer hence it was reasonable to predict the strong wet end to our current Summer. It was the prolonged period of limited rain that likely helped extend the recent fire activity. Interestingly as February 2020 rainfall unfolds it appears we are following the pattern for 1929 (including relevance of 6th February) unless even more rain arrives and then an event like the 1949 flood beckons! Next month we will explore flooding events in the Valley. If anyone has any access to detailed historical flood information for Wollombi please let the author know. -

Gauging Station Index

Site Details Flow/Volume Height/Elevation NSW River Basins: Gauging Station Details Other No. of Area Data Data Site ID Sitename Cat Commence Ceased Status Owner Lat Long Datum Start Date End Date Start Date End Date Data Gaugings (km2) (Years) (Years) 1102001 Homestead Creek at Fowlers Gap C 7/08/1972 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 19.9 -31.0848 141.6974 GDA94 07/08/1972 16/12/1995 23.4 01/01/1972 01/01/1996 24 Rn 1102002 Frieslich Creek at Frieslich Dam C 21/10/1976 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 8 -31.0660 141.6690 GDA94 19/03/1977 31/05/2003 26.2 01/01/1977 01/01/2004 27 Rn 1102003 Fowlers Creek at Fowlers Gap C 13/05/1980 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 384 -31.0856 141.7131 GDA94 28/02/1992 07/12/1992 0.8 01/05/1980 01/01/1993 12.7 Basin 201: Tweed River Basin 201001 Oxley River at Eungella A 21/05/1947 Open DWR 213 -28.3537 153.2931 GDA94 03/03/1957 08/11/2010 53.7 30/12/1899 08/11/2010 110.9 Rn 388 201002 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.1 C 27/05/1947 31/07/1957 Closed DWR 124 -28.3151 153.3511 GDA94 01/05/1947 01/04/1957 9.9 48 201003 Tweed River at Braeside C 20/08/1951 31/12/1968 Closed DWR 298 -28.3960 153.3369 GDA94 01/08/1951 01/01/1969 17.4 126 201004 Tweed River at Kunghur C 14/05/1954 2/06/1982 Closed DWR 49 -28.4702 153.2547 GDA94 01/08/1954 01/07/1982 27.9 196 201005 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.3 A 3/04/1957 Open DWR 111 -28.3096 153.3360 GDA94 03/04/1957 08/11/2010 53.6 01/01/1957 01/01/2010 53 261 201006 Oxley River at Tyalgum C 5/05/1969 12/08/1982 Closed DWR 153 -28.3526 153.2245 GDA94 01/06/1969 01/09/1982 13.3 108 201007 Hopping Dick Creek -

Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area Strategic Plan Addendum 2016

Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area Strategic Plan Addendum 2016 © 2018 State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) has compiled this report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. All content in this publication is owned by OEH and is protected by Crown Copyright, unless credited otherwise. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), subject to the exemptions contained in the licence. The legal code for the licence is available at Creative Commons. OEH asserts the right to be attributed as author of the original material in the following manner: © State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2018. Cover photograph: Kanangra Boyd National Park (Photo: Botanic Gardens Trust/Simone -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 86 Friday, 18 May 2001 Published Under Authority by the Government Printing Service

2587 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 86 Friday, 18 May 2001 Published under authority by the Government Printing Service LEGISLATION Regulations Medical Practice Amendment (Records Exemption) Regulation 2001 under the Medical Practice Act 1992 Her Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has made the following Regulation under the Medical Practice Act 1992. CRAIG KNOWLES, M.P., Minister for for Health Health Explanatory note The object of this Regulation is to amend the Medical Practice Regulation 1998 to exempt public health organisations, private hospitals, day procedure centres and nursing homes from the requirements in that Regulation to keep records relating to patients. This Regulation makes it clear that the exemption of those medical corporations from those requirements does not affect the application of those requirements to registered medical practitioners engaged by those medical corporations. This Regulation also provides that section 126 (2) of the Medical Practice Act 1992 is not affected. That provision requires that a record made under the Medical Practice Regulation 1998 be disposed of in a manner that will preserve the confidentiality of any information it contains relating to patients. This Regulation is made under the Medical Practice Act 1992, including sections 126 (Records to be kept) and 194 (the general regulation-making power). r00-381-p01.822 Page 1 2588 LEGISLATION 18 May 2001 Clause 1 Medical Practice Amendment (Records Exemption) Regulation 2001 Medical Practice Amendment (Records Exemption) Regulation 2001 1 Name of Regulation This Regulation is the Medical Practice Amendment (Records Exemption) Regulation 2001. 2 Amendment of Medical Practice Regulation 1998 The Medical Practice Regulation 1998 is amended as set out in Schedule 1. -

REPORTED in the MEDIA Newspapers

REPORTED IN THE MEDIA Newspapers • Mortgage Interest Rates The Age , Banks Dudding Customers for Years, 4/10/2012, Front page . The Sydney Morning Herald, The Big Banks Take with One Hand - and the Other , 4/10/ 2012, p.2 The results of my research on the RBA’s rate cuts and the asymmetric behaviour of Big 4 banks in setting their mortgage rates also attracted widespread media attention on 4 October 2012: Melbourne Weekly, Brisbane Times, Stock & Land, Stock Journal, The West Australian, Brisbane Times, Finders News, Southwest Advertiser, Daily Life, Dungog Chronicle, Western Magazine, Frankston Weekly, The Mercury , Sun City News . http://theage.com.au/business/the-big-banks-take-with-one-hand--and-the-other-20121003- 26ztm.html http://smh.com.au/business/the-big-banks-take-with-one-hand--and-the-other-20121003-26ztm.html http://nationaltimes.com.au/business/the-big-banks-take-with-one-hand--and-the-other-20121003- 26ztm.html • University Research Performance Just a Matter of Time Before Universities Take Off, Australian Financial Review , 31/7/2006, p.34 Melbourne on a High, The Australian , 26/7/2006, p.23. Smaller Universities Top of their Class, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20/7/2005, p.10. Sutton's New Vision, Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong), 21/7/2005, p.7. Uni Gets Top Grade, The Newcastle Herald, 20/7/2005, p. 21. • Petrol Prices Call for Bowser Boycott, The Telegraph , 28/3/2013, p.3. Pump your Pockets, Herald Sun , 28/3/2013, p.9. Drivers Urged to Fill Up on Cheaper Days, Courier Mail , 28/3/2013, p.11 Reward to Eagle-Eyed Motorists, Courier Mail, Brisbane, 10/8/2001, p.5. -

Canning Street Walk

WollombThe i Village Walks ANZAC RESERVE refer to Wollombi Village Walk for further details 2 kms approx. 1 hour Park cars here. Start. Grade: Easy, uneven track in the bush with some steps Welcome to Canning Street. This is a fun walk – but you will also learn a thing or three. Interested in bush plants? This is a great first step for those who want to recognise, and identify the plants of the Wollombi Valley. If you want to join in the fun, then tick the boxes beside the items on the other side of the map as you identify them and start on a fascinating botanical journey! For the bush part of this walk, see over Wollombi Village centre 1.2 kms 12 1 11 0 30 2 30 N 3 6 0 0 1 0 0 3 3 90 Canning Street E W W 1 1 270 270 9 9 2 2 0 0 4 4 Nature Track 0 0 4 4 1 1 2 2 5 5 0 0 S S 8 8 0 0 1 1 180 180 2 2 5 5 7 7 6 6 The old map of the Wollombi township On the second level from Narone creek Road, next to a Jacksonia there is a Not far from the persoonia This small area of Australian bush is an area of regenerated native bush and is ideal to gain an insight as to what grows in the area around Wollombi. For those good example of a Persoonia, it is a small open tree with needle like leaves, is an example of a Breynia, who enjoy walking in the bush and know little of the names of the plants this is a good first step to become aware of what shares this area with us. -

Snakes, Spiders and a Painter's Eye

REBECCA RATH BFA HONS Assoc. Dip Arts (Fine Arts) M: 0412572651 E: [email protected] W: www.rebeccarath.com.au Social Media: @rebeccarathart Snakes, Spiders and a Painter’s Eye. “Rebecca is an incredibly talented artist who has an innate ability to capture the very soul of the valley. I feel as if the land is speaking to me through her use of colour and texture on canvas - they remind me of home every time I gaze upon them and they evoke the heat, the intense storms, the very essence of the amazing landscape that is the Hunter (Australia). I love my paintings so much and feel privileged to have them in my home. I know I will collect more in the coming years.” Susan Arrowsmith. I close my eyes and feel the warm sun on my back, the circling sound of the wind in the grass and the sweep of my brush. There is nothing more tranquil, peaceful and wildly free than being in the Australian bush and painting her splendor. The idea of one of the world’s most venomous snakes do tug at the back of my mind, yet the lure of Australia’s vast plains and majestic skies always entice my painter’s curiosity. Her powerful colour palette and rogue visceral texture is a feast for any painter’s eye. At times it is challenging to get outside. Insects, spiders and snakes are at the back of my mind, when I sit among the tall grass and paint the sprawling landscape in front of my eyes. -

Congewai East Track Head to Watagan Forest Motel Via Forestry HQ Campsite

Congewai East Track Head to Watagan Forest Motel via Forestry HQ Campsite 2 Days Hard track 4 29.7 km One way 1702m This section of the Great North Walk starts from the Congewai Valley east track head and heads north up into the Watagan National Park, climbing up to the ridgeline and following the management trails and bush tracks heading east all the way to the Forestry HQ campsite. On day two, the walk continues east, winding all the way around the ridge and past some great lookouts to the Heaton communications tower and down the steep ridgeline to Freemans Drive and the Watagan Forest Motel. 513m 139m Watagans National Park Maps, text & images are copyright wildwalks.com | Thanks to OSM, NASA and others for data used to generate some map layers. Old Loggers Hut Before You walk Grade This Old Hut found beside Georges Rd, is in a state of disrepair. The Bushwalking is fun and a wonderful way to enjoy our natural places. This walk has been graded using the AS 2156.1-2001. The overall corrugated iron and wooden hut has a dirt floor and a simple fire Sometimes things go bad, with a bit of planning you can increase grade of the walk is dertermined by the highest classification along place. The hut's condition is poor and would not provide suitable your chance of having an ejoyable and safer walk. the whole track. shelter. Just south of the hut is a small dam. The hut was once used Before setting off on your walk check by loggers harvesting timber from these hills 1) Weather Forecast (BOM Hunter District) 4 Grade 4/6 2) Fire Dangers (Greater Hunter) Hard track Georges Road Rest Area 3) Park Alerts (Watagans National Park) 4) Research the walk to check your party has the skills, fitness and This campsite is located above Wallaby Gully, off Georges Road. -

The Vertebrate Fauna of Northern Yengo National Park

The Vertebrate Fauna of Northern Yengo National Park Project funded under the Central Branch Parks and Wildlife Division Biodiversity Survey Priorities Program Information and Assessment Section Metropolitan Branch Environmental Protection and Regulation Division Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) June 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project has been undertaken by Helen Hair and Scat Analysis Achurch, Elizabeth Magarey and Daniel Barbara Triggs Connolly from the Metropolitan Branch Information and Assessment, EPRD Bat Call Analysis Section Head, Information and Assessment Narawan Williams Julie Ravallion Special thanks to: Staff of the Hunter Range Area and Central Coordinator, Bioregional Data Group Coast Regional Office for assistance in Daniel Connolly planning and support during the surveys. Private Property owners for allowing us to stay GIS and Database Coordinator on their land and access the park through their Peter Ewin properties. Report Writing and Map Production Daniel Connolly This report should be referenced as follows: Helen Achurch DEC (2005) “The Vertebrate Fauna of Northern Yengo National Park.” Unpublished report Field Surveyors funded by the Central Branch Parks and Narawan Williams Wildlife Division Biodiversity Survey Priorities Martin Schulz Program by NSW Department of Environment Dion Hobcroft and Conservation, Information and Assessment Alex Dudley Section, Metropolitan Branch, Environment Elizabeth Magarey Protection and Regulation Division. Helen Achurch Richard Harris Doug Beckers All photographs are -

Business Wire Catalog

Asia-Pacific Media Pan regional print and television media coverage in Asia. Includes full-text translations into simplified-PRC Chinese, traditional Chinese, Japanese and Korean based on your English language news release. Additional translation services are available. Asia-Pacific Media Balonne Beacon Byron Shire News Clifton Courier Afghanistan Barossa & Light Herald Caboolture Herald Coast Community News News Services Barraba Gazette Caboolture News Coastal Leader Associated Press/Kabul Barrier Daily Truth Cairns Post Coastal Views American Samoa Baw Baw Shire & West Cairns Sun CoastCity Weekly Newspapers Gippsland Trader Caloundra Weekly Cockburn City Herald Samoa News Bay News of the Area Camden Haven Courier Cockburn Gazette Armenia Bay Post/Moruya Examiner Camden-Narellan Advertiser Coffs Coast Advocate Television Bayside Leader Campaspe News Collie Mail Shant TV Beaudesert Times Camperdown Chronicle Coly Point Observer Australia Bega District News Canberra City News Comment News Newspapers Bellarine Times Canning Times Condobolin Argus Albany Advertiser Benalla Ensign Canowindra News Coober Pedy Regional Times Albany Extra Bendigo Advertiser Canowindra Phoenix Cooktown Local News Albert & Logan News Bendigo Weekly Cape York News Cool Rambler Albury Wodonga News Weekly Berwick News Capricorn Coast Mirror Cooloola Advertiser Allora Advertiser Bharat Times Cassowary Coast Independent Coolum & North Shore News Ararat Advertiser Birdee News Coonamble Times Armadale Examiner Blacktown Advocate Casterton News Cooroy Rag Auburn Review -

The Knodler Family History and Register 1612

Published by GREGORY J.E. KNODLER B.A.(Psych), B.Ed.Stud (Post Grad), Dep.Ed.Stud(Counselling), Cert.T COPYRIGHT - No material may be copied without the written permission of the author: G.J.E. KNODLER, 22 Valentine Crescent, Valentine, NSW, Australia. CONTENTS Page Foreword 1 German Immigration to the Hunter Valley in the Mid 19th Century 8 Johann Gottlob and Anna Maria Knodler 20 John Frederick and Christiana Knodler 30 George and Louisa Knodler 38 Gottlob Henry and Anne Knodler 44 The Knodler Family since 1612 50 Earle Henry and Betsie Rebecca Knodler 98 1 <8ri man* Since the name Knodler is not uncommon in Germany, it had always seemed like an impossible task to trace the origins of the Knodler family. When in the 1970s one had only a page in the family Bible indicating the names of the first Knodlers to arrive in Australia, together with the information that they had come from Wurttemberg (a State in Germany) the possibility of tracing ancestors earlier than those of the Australian period seemed rather remote. This was also still the period when very little documentation was readily available to those who wished to chart their family tree. In 1971, I married Miss Judith Steller from Dural, NSW. Some time after this, a remarkable set of circumstances evolved which were to allow the gathering of information previously thought impossible to obtain. Judy's father, Mr Hugo Steller, had been born in Palestine. He was a member of a religious group formed when it left the Wurttemberg area in Germany in the 1800s to settle in Palestine. -

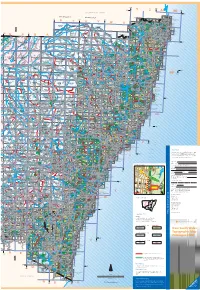

New South Wales Topographic Map Catalogue 2008

° 152 153° Y 154° 28° Z AA BB QUEENSLAND 28° Coolangatta SPRING- CURRU- TWEED HEAD WARWICK BROOK MBIN SFingal Head AMG / MGA ZONE 55 AMG /MGA ZONE 56 MT LINDESAY MURWILLUMBAH 9641-4S 9341 Terranora TWEED HEADS KILLAR- WILSON M 9441 LAM- TYAL- S MOUNT OUNT PALEN 9541Tumbulgum Kingscliff 151° NEY PEAK LINDE- COUGAL INGTON GUM MURWILLUMBAH 9641 ° ° CLUNIE CREEK CUDGEN 149 150 KOREELAH N P SAY TYALGUMChillingham9541-2N Condong Bogangar Woodenbong 96 Legume BORDER RANGES 9541-3-N I 41-3N N P Old Hastings Point S EungellaTWEEDI ELBOW VALLEY KOREE TOOLOOM Grevillia MOOBALL NP V LAH I T WOOD MT. WARNING U N P ENBONG Uki Pottsville Beach G W 9341-3-S REVILLIA BRAYS N P 9341-2-S CREEK 9441 BURRINGB I POTTSVIL X -3-S AI R LE 9441-2-S Mount I Grevillia 9541-3S 9541-2 Mooball Goondiwindi Urbenville Lion S 9641-3S TOONUMBAR N P MEBBIN N P MOUNT I MARYLAND Kunghur JERUSALEM N P Wiangaree I N P WYLIE CREEK TOOLOOM NIGHTCAP Ocean Shores GRADULE BOOMI CAPEEN AFTERLE Mullumbimby BOGGABILLA YELARBO 9340-4-N 9340 E NIMBIN N P I 8740-N I N -1-N 9440-4-N HUONBROOK BRUNSWICK 8840-N 9440-1-N I 8940-N 9040-N 9540-4N Nimbin 9540-1NBYRON I Toonumbar I HEA Liston Tooloom GOONENGERRY NP DS I Rivertree Old Bonalbo RICHMOND KYOGLE Cawongla I 9640-4N Kyogle I Boomi I LISTON RANGE N P PADDYS FLATYABBRA BONALBO LISMORERosebank Federal ETTRIC I Byron Bay GO I N P K ONDIWINDI YETMAN 9340-4-S 9340-1-S LARNOOK The D BYRON BAY S R A TEXAS 9440-4-S UNOON BI YRI ON BA STANTHORP Paddys Flat 9440-1-S Cedar 9540 Channon I Y 8940 I E DRAKE -4S 9540-1S Suffolk Park 9040 BON Dryaaba