Download Chapter (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Branches with Vacant Lockers

Union Bank of India List of Branches having Vacant Lockers State District Branch Name Branch Address Branch Adrress 2 Phone Andaman-Nicobar Andaman PORT BLAIR 10.Gandhi Bhavan, Aberdeen Bazar, Port Blair, Dist. Andaman, 233344 Andhra Pradesh Anantapur HINDUPUR Ground Floor, Dhanalakshmi Road, SD-Hindupur, Dist.Anantapur, 227888 Andhra Pradesh Ananthpur KIRIKERA At & Post Kirikera, Tal. Hindupur, Dist. Anantpur, Andhra Pradesh, 247656 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor SRIKALAHASTI 6-166, Babu Agraharam, Srikalahasti Town, PO Srikalahasti, S.Dist. Srikalahasti, 222285 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor PUNGANUR Survey No. 129, First Floor, Opp. MPDO Office, Madanapalle Road, PO Punganur, 250794 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari RAMACHANDRAPURAM D No:11-01 6/7,Jayalakshmi Complex, Nr Matangi hotel, Opp Town Bank, Main Road, PO & SD 9494952586 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari EETHAKOTA FI Mani Road Eethakota, Near Vedureswaram, Ravulapalem Mandal, Dist: East Godavari, 09000199511 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari SAMALKOT D.No.11-2-24, Peddapuram Road, East Godavari District, Samalkot 2327977 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari MANDAPETA Door No. 34-16-7, Kamath Arcade, Main Road, Post Mandepeta, Dist. East Godavari, 234678 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari SARPAVARAM,KAKINADA DoorNo10-134,OPP Bhavani Castings,First Floor Sri Phani Bhushana Steel Pithapuram Road 2366630 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari TUNI Door No. 8-10-58, Opp. Kanyaka Parameswari Temple, Bellapu Veedhi, Tuni, Dist. 251350 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari VEDURESWARAM At&Post. Vedureswaram, Via Ravulapalem Mandal, Taluka Kothapet, Dist. East Godavari, 255384 KAMBALACHERUVU,RAJAHMUND Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Ground Floor,Yamuna Nilayam,DoorNo26-2-6, Koppisettyvari Street,PO Sriramnagar, 2555575 RY Andhra Pradesh Guntur RAVIPADU Door No.3-76 A, Main Road, PO Pavipadu (Guntur),S.Dist Narasaraopet 222267 Andhra Pradesh Guntur NARASARAOPET 909044 to 46, Bank Street, Arundelpet, P.O. -

Initial Environmental Examination IND: Visakhapatnam Chennai Industrial Corridor Development Program (VCICDP)

Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 48434 March 2016 IND: Visakhapatnam Chennai Industrial Corridor Development Program (VCICDP) Naidupeta Economic Zone Subproject – Common Effluent Treatment Plant at Naidupeta and Atchutapuram Industrial Estates Prepared by the Government of Andhra Pradesh for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 08 March 2016) Currency unit – Indian rupee (Rs) Rs1.00 = $0.0149 $1.00 = INR66.9940 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank APIIC - Andhra Pradesh Industrial and Infrastructure Corporation Limited BGL - Below Ground Level BOD - Biological Oxygen Demand BIS - Bureau of Indian Standard CPCB - Central Pollution Control Board DO - Dissolved Oxygen DoE - Department of Environment PMC - Project Management Consultant EA - Executing Agency EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EMP - Environmental Management Plan EMoP - Environmental Monitoring Plan ESO - Environmental and Safety Officer GoAP - Government of Andhra Pradesh GoI - Government of India IEE - Initial Environmental Examination IMD - Indian Meteorological Department IS - Indian Standard MFF - Multi Tranche Financial Facility MoEF - Ministry of Environment and Forests MSL - Mean Sea Level MW - Mega Watt NGO - Non - Government Organization NOx - Oxides of Nitrogen APIIC - Project Implementation Unit RF - Reserve Forest ROW - Right of Way PMSC - Project Management and Supervision Consultant SPCB - State Pollution Control Board SPM - Suspended Particulate Matter SO2 - Sulphur Dioxide SSI - Small Scale Industries -

Indian Archaeology 1972-73

INDIAN ARCHAEOLOGY 1972-73 —A REVIEW EDITED BY M. N. DESHPANDE Director General Archaeological Survey of India ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI 1978 Cover Recently excavated caskets from Piprahwa 1978 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Price : Rs. 40.00 PRINTED AT NABA MUDRAN PRIVATE LTD., CALCUTTA, 700004 PREFACE Due to certain unavoidable reasons, the publication of the present issue has been delayed, for which I crave the indulgence of the readers. At the same time, I take this opportunity of informing the readers that the issue for 1973-74 is already in the Press and those for 1974-75 and 1975-76 are press-ready. It is hoped that we shall soon be up to date in the publication of the Review. As already known, the Review incorporates all the available information on the varied activities in the field of archaeology in the country and as such draws heavily on the contributions made by the organizations outside the Survey as well, viz. the Universities and other Research Institutions, including the Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmadabad and the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany, Lucknow, and the State Departments of Archaeology. My grateful thanks are due to all contributors, including my colleagues in the Survey, who supplied the material embodied in the Review as also helped me in editing and seeing it through the Press. M. N. DESHPANDE New Delhi 1 October 1978 CONTENTS PAGE I. Explorations and Excavations ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 1 Andhra Pradesh, 1; Arunachal, 3; Bihar, 3; Delhi, 8; Gujarat, 9; Haryana, 12; Jammu and Kashmir, 13; Kerala, 14; Madhya Pradesh, 14; Maharashtra, 20; Mysore, 25; Orissa, 27; Punjab, 28; Rajasthan, 28; Tamil Nadu, 30; Uttar Pradesh, 33; West Bengal, 35. -

Shankar Ias Academy Test 18 - Geography - Full Test - Answer Key

SHANKAR IAS ACADEMY TEST 18 - GEOGRAPHY - FULL TEST - ANSWER KEY 1. Ans (a) Explanation: Soil found in Tropical deciduous forest rich in nutrients. 2. Ans (b) Explanation: Sea breeze is caused due to the heating of land and it occurs in the day time 3. Ans (c) Explanation: • Days are hot, and during the hot season, noon temperatures of over 100°F. are quite frequent. When night falls the clear sky which promotes intense heating during the day also causes rapid radiation in the night. Temperatures drop to well below 50°F. and night frosts are not uncommon at this time of the year. This extreme diurnal range of temperature is another characteristic feature of the Sudan type of climate. • The savanna, particularly in Africa, is the home of wild animals. It is known as the ‘big game country. • The leaf and grass-eating animals include the zebra, antelope, giraffe, deer, gazelle, elephant and okapi. • Many are well camouflaged species and their presence amongst the tall greenish-brown grass cannot be easily detected. The giraffe with such a long neck can locate its enemies a great distance away, while the elephant is so huge and strong that few animals will venture to come near it. It is well equipped will tusks and trunk for defence. • The carnivorous animals like the lion, tiger, leopard, hyaena, panther, jaguar, jackal, lynx and puma have powerful jaws and teeth for attacking other animals. 4. Ans (b) Explanation: Rivers of Tamilnadu • The Thamirabarani River (Porunai) is a perennial river that originates from the famous Agastyarkoodam peak of Pothigai hills of the Western Ghats, above Papanasam in the Ambasamudram taluk. -

03404349.Pdf

UA MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT STUDY GROUP Jagdish M. Bhagwati Nazli Choucri Wayne A. Cornelius John R. Harris Michael J. Piore Rosemarie S. Rogers Myron Weiner a ........ .................. ..... .......... C/77-5 INTERNAL MIGRATION POLICIES IN AN INDIAN STATE: A CASE STUDY OF THE MULKI RULES IN HYDERABAD AND ANDHRA K.V. Narayana Rao Migration and Development Study Group Center for International Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 August 1977 Preface by Myron Weiner This study by Dr. K.V. Narayana Rao, a political scientist and Deputy Director of the National Institute of Community Development in Hyderabad who has specialized in the study of Andhra Pradesh politics, examines one of the earliest and most enduring attempts by a state government in India to influence the patterns of internal migration. The policy of intervention began in 1868 when the traditional ruler of Hyderabad State initiated steps to ensure that local people (or as they are called in Urdu, mulkis) would be given preferences in employment in the administrative services, a policy that continues, in a more complex form, to the present day. A high rate of population growth for the past two decades, a rapid expansion in education, and a low rate of industrial growth have combined to create a major problem of scarce employment opportunities in Andhra Pradesh as in most of India and, indeed, in many countries in the third world. It is not surprising therefore that there should be political pressures for controlling the labor market by those social classes in the urban areas that are best equipped to exercise political power. -

LHA Recuritment Visakhapatnam Centre Screening Test Adhrapradesh Candidates at Mudasarlova Park Main Gate,Visakhapatnam.Contact No

LHA Recuritment Visakhapatnam centre Screening test Adhrapradesh Candidates at Mudasarlova Park main gate,Visakhapatnam.Contact No. 0891-2733140 Date No. Of Candidates S. Nos. 12/22/2014 1300 0001-1300 12/23/2014 1300 1301-2600 12/24/2014 1299 2601-3899 12/26/2014 1300 3900-5199 12/27/2014 1200 5200-6399 12/28/2014 1200 6400-7599 12/29/2014 1200 7600-8799 12/30/2014 1177 8800-9977 Total 9977 FROM CANDIDATES / EMPLOYMENT OFFICES GUNTUR REGISTRATION NO. CASTE GENDER CANDIDATE NAME FATHER/ S. No. Roll Nos ADDRESS D.O.B HUSBAND NAME PRIORITY & P.H V.VENKATA MUNEESWARA SUREPALLI P.O MALE RAO 1 1 S/O ERESWARA RAO BHATTIPROLU BC-B MANDALAM, GUNTUR 14.01.1985 SHAIK BAHSA D.NO.1-8-48 MALE 2 2 S/O HUSSIAN SANTHA BAZAR BC-B CHILAKURI PETA ,GUNTUR 8/18/1985 K.NAGARAJU D.NO.7-2-12/1 MALE 3 3 S/O VENKATESWARULU GANGANAMMAPETA BC-A TENALI. 4/21/1985 SHAIK AKBAR BASHA D.NO.15-5-1/5 MALE 4 4 S/O MAHABOOB SUBHANI PANASATHOTA BC-E NARASARAO PETA 8/30/1984 S.VENUGOPAL H.NO.2-34 MALE 5 5 S/O S.UMAMAHESWARA RAO PETERU P.O BC-B REPALLI MANDALAM 7/20/1984 B.N.SAIDULU PULIPADU MALE 6 6 S/O PUNNAIAH GURAJALA MANDLAM ,GUNTUR BC-A 6/11/1985 G.RAMESH BABU BHOGASWARA PET MALE 7 7 S/O SIVANJANEYULU BATTIPROLU MANDLAM, GUNTUR BC-A 8/15/1984 K.NAGARAJENDRA KUMAR PAMIDIMARRU POST MALE 8 8 S/O. -

List-Of-TO-STO-20200707191409.Pdf

Annual Review Report for the year 2018-19 Annexure 1.1 List of DTOs/ATOs/STOs in Andhra Pradesh (As referred to in para 1.1) Srikakulam District Vizianagaram District 1 DTO, Srikakulam 1 DTO, Vizianagaram 2 STO, Narasannapeta 2 STO, Bobbili 3 STO, Palakonda 3 STO, Gajapathinagaram 4 STO, Palasa 4 STO, Parvathipuram 5 STO, Ponduru 5 STO, Salur 6 STO, Rajam 6 STO, Srungavarapukota 7 STO, Sompeta 7 STO, Bhogapuram 8 STO, Tekkali 8 STO, Cheepurupalli 9 STO, Amudalavalasa 9 STO, Kothavalasa 10 STO, Itchapuram 10 STO, Kurupam 11 STO, Kotabommali 11 STO, Nellimarla 12 STO, Hiramandalam at Kothur 12 STO, Badangi at Therlam 13 STO, Pathapatnam 13 STO, Vizianagaram 14 STO, Srikakulam East Godavari District 15 STO, Ranasthalam 1 DTO, East Godavari Visakhapatnam District 2 STO, Alamuru 1 DTO, Visakhapatnam 3 STO, Amalapuram 2 STO, Anakapallli (E) 4 STO, Kakinada 3 STO, Bheemunipatnam 5 STO, Kothapeta 4 STO, Chodavaram 6 STO, Peddapuram 5 STO, Elamanchili 7 DTO, Rajahmundry 6 STO, Narsipatnam 8 STO, R.C.Puram 7 STO, Paderu 9 STO, Rampachodavaram 8 STO, Visakhapatnam 10 STO, Rayavaram 9 STO, Anakapalli(W) 11 STO, Razole 10 STO, Araku 12 STO, Addateegala 11 STO, Chintapalli 13 STO, Mummidivaram 12 STO, Kota Uratla 14 STO, Pithapuram 13 STO, Madugula 15 STO, Prathipadu 14 STO, Nakkapalli at Payakaraopeta 16 STO, Tuni West Godavari District 17 STO, Jaggampeta 1 DTO, West Godavari 18 STO, Korukonda 2 STO, Bhimavaram 19 STO, Anaparthy 3 STO, Chintalapudi 20 STO, Chintoor 4 STO, Gopalapuram Prakasam District 5 STO, Kovvur 1 ATO, Kandukuru 6 STO, Narasapuram -

The Madras Presidency, with Mysore, Coorg and the Associated States

: TheMADRAS PRESIDENG 'ff^^^^I^t p WithMysore, CooRGAND the Associated States byB. THURSTON -...—.— .^ — finr i Tin- PROVINCIAL GEOGRAPHIES Of IN QJofttell HttinerHitg Blibracg CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Digitized by Microsoft® Cornell University Library DS 485.M27T54 The Madras presidencypresidenc; with MysorMysore, Coor iliiiiliiiiiiilii 3 1924 021 471 002 Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Provincial Geographies of India General Editor Sir T. H. HOLLAND, K.C.LE., D.Sc, F.R.S. THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES Digitized by Microsoft® CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS HonBnn: FETTER LANE, E.G. C. F. CLAY, Man^gek (EBiniurBi) : loo, PRINCES STREET Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO. Ji-tipjifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS i^cto Sotfe: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS iBomlaj sriB Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. All rights reserved Digitized by Microsoft® THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES BY EDGAR THURSTON, CLE. SOMETIME SUPERINTENDENT OF THE MADRAS GOVERNMENT MUSEUM Cambridge : at the University Press 1913 Digitized by Microsoft® ffiambttige: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. Digitized by Microsoft® EDITOR'S PREFACE "HE casual visitor to India, who limits his observations I of the country to the all-too-short cool season, is so impressed by the contrast between Indian life and that with which he has been previously acquainted that he seldom realises the great local diversity of language and ethnology. -

Annual Report 2017-2018

ANNUAL REPORT IISc 2017-18 INDIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE VISITOR The President of India PRESIDENT OF THE COURT N Chandrasekaran CHAIRMAN OF THE COUNCIL P Rama Rao DIRECTOR Anurag Kumar DEANS SCIENCE: Biman Bagchi ENGINEERING: K Kesava Rao UG PROGRAMME: Anjali A Karande REGISTRAR V Rajarajan Pg 3 IISc RANKED INDIA’S TOP UNIVERSITY In 2016, IISc was ranked Number 1 among universities by the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) under the auspices of the Ministry of Human Resource Development. It was the first time the NIRF came out with rankings for Indian universities and institutions of higher education. In both 2017 and 2018, the Institute was again ranked first among universities, as well as first in the overall category. CONTENTS Foreword IISc at a Glance 8 1. The Institute 18 Court 5 Council 20 Finance Committee 21 Senate 21 Faculties 21 2. Staff (administration) 22 3. Divisions 25 3.1 Biological Sciences 26 3.2 Chemical Sciences 58 3.3 Electrical, Electronics, and Computer Sciences 86 3.4 Interdisciplinary Research 110 3.5 Mechanical Sciences 140 3.6 Physical and Mathematical Science 180 3.7 Centres under the Director 206 4. Undergraduate Programme 252 5. Awards/Distinctions 254 6. Students 266 6.1 Admissions & On Roll 267 6.2 SC/ST Students 267 6.3 Scholarships/Fellowships 267 6.4 Assistance Programme 267 6.5 Students Council 267 6.6 Hostels 267 6.7 Institute Medals 268 6.8 Awards & Distinctions 269 6.9 Placement 279 6.10 External Registration Program 279 6.11 Research Conferments 280 7. Events 300 7.1 Institute Lectures 310 7.2 Conferences/Seminars/Symposia/Workshops 302 8. -

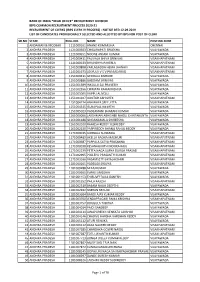

Clerks (Ibps Clerk Ix Process) - Notice Dtd 12.09.2019 List of Candidates Provisionally Selected and Allotted by Ibps for Post of Clerk

BANK OF INDIA *HEAD OFFICE* RECRUITMENT DIVISION IBPS COMMON RECRUITMENT PROCESS 2020-21 RECRUITMENT OF CLERKS (IBPS CLERK IX PROCESS) - NOTICE DTD 12.09.2019 LIST OF CANDIDATES PROVISIONALLY SELECTED AND ALLOTTED BY IBPS FOR POST OF CLERK SR.NO STATE ROLL.NO. NAME POSTING ZONE 1 ANDAMAN & NICOBAR 1111000161 ANAND KUMAR JHA CHENNAI 2 ANDHRA PRADESH 1121000303 CHIGURUPATI SRILEKHA VIJAYAWADA 3 ANDHRA PRADESH 1121000651 NOONE ANJANI KUMAR VIJAYAWADA 4 ANDHRA PRADESH 1141000411 PALIVALA SHIVA SRINIVAS VISAKHAPATNAM 5 ANDHRA PRADESH 1141000633 BHAVISHYA PAKERLA VISAKHAPATNAM 6 ANDHRA PRADESH 1141000808 YARLAGADDA HEMA JAHNAVI VISAKHAPATNAM 7 ANDHRA PRADESH 1141001673 JOSYULA V S V PRASADARAO VISAKHAPATNAM 8 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151000411 GEDDALA KISHORE VIJAYAWADA 9 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151000886 GADDAM SRINIVAS VIJAYAWADA 10 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151001389 INKOLLU SAI PRAVEEN VIJAYAWADA 11 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151002556 CHIMATA RAMAKRISHNA VIJAYAWADA 12 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151003005 VUPPU ALIVELU VIJAYAWADA 13 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151004107 GUNTUR ABHISHEK VISAKHAPATNAM 14 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151004274 ABHINAYA SREE JITTA VIJAYAWADA 15 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151004515 ISUKAPALLI KEERTHI VIJAYAWADA 16 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151005023 VADLAMANI BHARANI KUMAR VIJAYAWADA 17 ANDHRA PRADESH 1161000066 LAKSHMAN ABHISHEK NAIDU CHINTAKUNTA VIJAYAWADA 18 ANDHRA PRADESH 1161001188 SINGANAMALA SHIREESHA VIJAYAWADA 19 ANDHRA PRADESH 1161002020 RAMESH REDDY YESIREDDY VIJAYAWADA 20 ANDHRA PRADESH 1161002630 PAPPIREDDY BHANU RAHUL REDDY VIJAYAWADA 21 ANDHRA PRADESH 1171000015 GUBBALA SUNANDA VISAKHAPATNAM -

Hand Book of Statistics-2015 Srikakulam District

HAND BOOK OF STATISTICS-2015 SRIKAKULAM DISTRICT COMPILED & PUBLISHED BY CHIEF PLANNING OFFICER SRIKAKULAM DR.P.Laxminarasimham, I.A.S., Collector & District Magistrate, Srikakulam. PREFACE The “HAND BOOK OF STATISTICS” for the year 2015 is 32nd in its series. It contains valuable Statistical Data relating to different Sectors and Departments in Srikakulam District. Basic data is a prime requisite in building up strategic plans with time bound targets. I hope this publication will be very useful to all General Public, Planners, Research Scholars, Administrators, Bankers and Other Organizations. I am very much thankful to all the District Officers for extending their co-operation in supplying the data relating to their sectors to bring out this publication as a ready reckoner. I appreciate the efforts made by Sri M.Sivarama Naicker, Chief Planning Officer, Srikakulam and his staff members for the strenuous efforts in compiling and bringing out the “HAND BOOK OF STATISTICS” for the year 2015. Any constructive suggestion for improvement of this publication and coverage of Statistical Data would be appreciated. Date: -11-2016, Place: Srikakulam. District Collector, Srikakulam. OFFICERS AND STAFF ASSOCIATED WITH THE PUBLICATION 1.SRI. M.SIVARAMA NAICKER CHIEF PLANNING OFFICER 2.SRI. CH.VASUDEAVRAO DEPUTY DIRECTOR 3.SMT. VSSL PRASANNA ASSISTANT DIRECTOR 4.SRI. V.MALLESWARA RAO STATISTICAL OFFICER 5.SRI. J.LAKSHMANA RAO STATISTICAL OFFCIER DATA COMPILATION: 1. SRI. D.VENKATARAMANA DY. STATISTICAL OFFICER 2. SRI. D.SASIBHUSHANA RAO DY. STATISTICAL OFFICER DATA PROCESSING & COMPUTERISATION: 1. SRI. D.VENKATARAMANA DY. STATISTICAL OFFICER 2. SRI. D.SASIBHUSHANA RAO DY. STATISTICAL OFFICER 3. SRI. P.YOGESWARA RAO COMPUTER OPERATOR CONTENTS TABLE CONTENTS PAGE NO NO. -

VOTER TURN out in ANDHRA PRADESH ASSEMBLY ELECTION-2019(Overall 79.91%)

VOTER TURN OUT IN ANDHRA PRADESH ASSEMBLY ELECTION-2019(Overall 79.91%) Constituency number and Name % of Votes Polled in Assembly election 2019 1 Ichchapuram 70.26 2 Palasa 72.92 3 Tekkali 78.79 4 Pathapatnam 70.23 5 Srikakulam 69.96 6 Amadalavalasa 78.51 7 Etcherla 84.3 8 Narasannapeta 80 9 Rajam (SC) 73.73 10 Palakonda (ST) 73.68 11 Kurupam (ST) 77.32 12 Parvathipuram (SC) 76.78 13 Salur (ST) 79 14 Bobbili 79.77 15 Cheepurupalli 83.07 16 Gajapathinagaram 86.73 17 Nellimarla 87.79 18 Vizianagaram 70.88 19 Srungavarapukota 85.69 20 Bhimili 73.9 21 Visakhapatnam East 64.73 22 Visakhapatnam South 61.15 23 Visakhapatnam North 62.65 24 Visakhapatnam West 58.19 25 Gajuwaka 65.84 26 Chodavaram 84.26 27 Madugula 83.67 28 Araku Valley (ST) 70.45 29 Paderu (ST) 61.8 30 Anakapalle 77.54 31 Pendurthi 74.89 32 Yelamanchili 84.49 33 Payakaraopet (SC) 81.74 34 Narsipatnam 82.33 35 Tuni 82.28 36 Prathipadu 81.01 37 Pithapuram 80.99 38 Kakinada Rural 74.12 39 Peddapuram 81.39 40 Anaparthy 87.48 41 Kakinada City 66.38 42 Ramachandrapuram 87.11 43 Mummidivaram 83.81 44 Amalapuram (SC) 82.5 45 Razole (SC) 79.34 46 Gannavaram (SC) 83.09 47 Kothapeta 84.3 48 Mandapeta 87.02 49 Rajanagaram 87.47 50 Rajahmundry City 66.34 51 Rajahmundry Rural 100 52 Jaggampeta 85.86 53 Rampachodavaram (ST) 77.82 54 Kovvur (SC) 86.41 55 Nidadavole 85.02 56 Achanta 81.46 57 Palacole 81.55 58 Narasapuram 82.86 59 Bhimavaram 78.06 60 Undi 84.8 61 Tanuku 80.54 62 Tadepalligudem 80.34 63 Unguturu 86.86 64 Denduluru 84.7 65 Eluru 66.31 66 Gopalapuram (SC) 100 67 Polavaram (ST) 86.55