2014 Environmental Resource Inventory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Minutes of a Regular Meeting of the Verona Township Council On

Minutes of a Regular Meeting of the Verona Township Council on Monday, March 6, 2017 beginning at 7:00 P.M. in the Municipal Building, 600 Bloomfield Avenue, Verona, New Jersey. Call to Order: Municipal Clerk reads notice of Open Public Meetings law. Roll Call: Mayor Kevin Ryan; Deputy Mayor Michael Nochimson; Councilman Bob Manley and Councilman Alex Roman are present. Township Manager Matthew Cavallo, Township Attorney Brian Aloia and Jennifer Kiernan, Municipal Clerk are also present. Councilman Jay Sniatkowski is not in attendance this evening. Verona Cub Scouts, Den 2, Pack 32 lead the Pledge of Allegiance. Mayor’s Report: Mayor Ryan speaks about the tragic accident Friday morning where two residents were struck by a vehicle on the corner of Pease and Lakeside Avenues. One victim, Megan E. Villanella succumbed to her injuries. Her brother was critically injured. Mayor Ryan calls Police Chief Mitchell Stern to the lectern. Chief Stern states he has received numerous emails about the incident. He states it is a fluid and fast moving investigation. No determination has been made at this time as to the cause of the accident. The investigation will conclude in due time as the Essex County Prosecutors Office and the Verona Detective Bureau continue to work to resolve the issue. The police department will continue with aggressive enforcement of traffic and vehicles laws. Mayor Ryan calls for public participation on this topic only as he notes many residents are present this evening regarding this issue. Virginia Russo – 7 Howard Street, Verona, NJ Carol and Philip Kirsch – 93 Cedar Street, Millburn, NJ Peter Till – 62 Lakeside Avenue, Verona, NJ Mayor Ryan invites Essex County liaison, Julius Coltre to the lectern. -

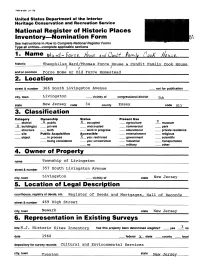

Nomination Form 2. Location 3. Classification 4. Owner of Property

FHR-«-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory — Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries — complete applicable sections 1. Name - forae, 0 oc>K historic Theophilus Ward/Thomas Force House & Condit Family Cook House 7 and/or common Force Home or Old Force Homestead 2. Location street & number 366 South Livingston Avenue not for publication city, town Livingston vicinity of congressional district 5£h state New Jersey code 34 county Essex code 013 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use y district X public X occupied agriculture museum X building(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other; 4. Owner of Property name Township of Livingston street & number 357 South Livingston Avenue city, town Livingston vicinity of state New Jersey 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Register of Deeds and Mortgages, Hall of Records street & number 469 High Street city, town Newark state New Jersey 6. Representation in Existing Surveys titieN.J. Historic Sites Inventory has this property been determined elegible? __yes __no date 1960 . federal -X_ state __ county __ local depository for survey records Cultural -

Military History Anniversaries 16 Thru 30 June

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 30 June Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Jun 16 1832 – Native Americans: Battle of Burr Oak Grove » The Battle is either of two minor battles, or skirmishes, fought during the Black Hawk War in U.S. state of Illinois, in present-day Stephenson County at and near Kellogg's Grove. In the first skirmish, also known as the Battle of Burr Oak Grove, on 16 JUN, Illinois militia forces fought against a band of at least 80 Native Americans. During the battle three militia men under the command of Adam W. Snyder were killed in action. The second battle occurred nine days later when a larger Sauk and Fox band, under the command of Black Hawk, attacked Major John Dement's detachment and killed five militia men. The second battle is known for playing a role in Abraham Lincoln's short career in the Illinois militia. He was part of a relief company sent to the grove on 26 JUN and he helped bury the dead. He made a statement about the incident years later which was recollected in Carl Sandburg's writing, among others. Sources conflict about who actually won the battle; it has been called a "rout" for both sides. The battle was the last on Illinois soil during the Black Hawk War. Jun 16 1861 – Civil War: Battle of Secessionville » A Union attempt to capture Charleston, South Carolina, is thwarted when the Confederates turn back an attack at Secessionville, just south of the city on James Island. -

The Antigua Press and Benjamin Mecom, 1748-17651

1928.] The Antigua Press 303 THE ANTIGUA PRESS AND BENJAMIN MECOM, 1748-17651 BY WILBERFOECE EAMES HE close relation existing between printing and the T post-ofiB.ce has been set forth in an interesting way by Mr. Worthington C. Ford in a series of letters from James Parker to Benjamin Franklin, printed for the first time in the Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1902.2 Franklin was appointed postmaster of Philadelphia in 1737, when thirty-one years of age, and in 1753 he was made deputy-postmaster-general of the British Colonies on the continent. These positions were an advantage to him in extending his connections, and at the same time an inducement to establish printing presses and gazettes in other places. The most im- portant of these branches was in the City of New York, where he entered into a co-partnership with James Parker in 1742 for starting a new press and newspaper. The Articles of Agreement, dated February 20, 1741- 42, were printed in Mr. Ford's paper, and show that Franklin was to provide the printing press and type, pay the cost of freight to New York, and bear one- third of the current expenses. In return he was to have one-third of the profits. Several of the British West India islands had printers and newspapers, like Jamaica, Barbados and St. Kitts; but Antigua, fifty miles east of the latter, >In the preparation of tMs paper I am under special obligations to Dr. A. S. W. Eosenbach, who first started me on it, and who has supplied most of the extracts which are herein quoted, from the original letters of Franklin in his possession. -

Final ERI Draft

Deptford Township Environmental Resource Inventory DRAFT April 2010 The Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission is dedicated to uniting the region’s elected officials, planning professionals and the public with the common vision of making a great region even greater. Shaping the way we live, work and play, DVRPC builds consensus on improving transportation, promoting smart growth, protecting the environment, and enhancing the economy. We serve a diverse region of nine counties: Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery and Philadelphia in Pennsylvania; and Burlington, Camden, Gloucester and Mercer in New Jersey. DVRPC is the official Metropolitan Planning Organization for the Greater Philadelphia Region — leading the way to a better future. The symbol in our logo is adapted from the official DVRPC seal, and is designed as a stylized image of the Delaware Valley. The circular shape symbolizes the region as a whole. The diagonal line represents the Delaware River and the two adjoining crescents represent the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the State of New Jersey. DVRPC is funded by a variety of funding sources including federal grants from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA), the Pennsylvania and New Jersey departments of transportation, as well as by DVRPC’s state and local member governments. The authors, however, are solely responsible for the findings and conclusions herein, which may not represent the official views or policies of the funding agencies. DVRPC fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. DVRPC’s website may be translated into Spanish, Russian and Traditional Chinese online by visiting www.dvrpc.org. -

Sierran Summer 05.Qxd

DATED MATERIAL DO NOT DELAY Nonprofit Organization-Sierra Club U.S.Postage PAID The Jersey••••••••••• IERRANIERRAN Vol. 34, No. 2 SS 23,000 Members in New Jersey April-June 2005 Sierra Club Rallies in Jon Corzine Endorsed Defense of Arctic for Governor By Rich Isaac, Chapter Political Chair Refuge — Once Again In its earliest ever endorsement for ing government — giving citizens a an open statewide seat here in New voice, and to working towards strong or at least 25 years (since Ronald Jersey, the Sierra Club has voted to sup- implementation of the State’s Highlands Reagan’s presidency from 1980 to port U.S. Senator Jon Corzine’s candida- law. He strongly supports family plan- F1988) environmentalists have cy for Governor. ning programs, the use of alternative opposed the use of a 5% portion of the Senator Corzine has demonstrated energy, and protecting New Jersey citi- northern Alaska coastline for oil explo- national leadership in protecting the zens from exposure to toxics. He is also ration and production, on grounds that its environment. He would bring his integri- very committed to making New Jersey a use for calving by native species, especial- ty and leadership to the Statehouse. leader in efforts to reduce global warm- ly caribou, entitled it to protection. The Corzine skillfully moved the Highlands ing, and the Club looks forward to work- area is within the Arctic National Wildlife Stewardship Act through the Senate. ing with him on an array of measures to Refuge, and borders Canada’s Yukon This important initiative, signed into law deal with this very critical issue. -

Notes on Old Gloucester County, New Jersey

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com OLD GLOUCESTER COUNTY COURT HOUSE AT WOODBURY. FROM SKETCH BY FRANK H. TAYLOR NOTES ON Old Gloucester County NEW JERSEY Historical Records Published by The New Jersey Society of Pennsylvania volume I Compiled and Edited by FRANK H. STEWART HISTORIAN OF THE SOCIETY 1917 0 Copyeighted 1917, ey The New Jeesey Society of Pennsylvania Peinted ey Sinnickson Chew & Sons Company Camden, New Jeesey New Jersey Down from thy hills the streams go leaping, Up from thy shores the tides come creeping, In bay and river the waters meet, Singing and singing with rhythmic beat Songs no orchestra may repeat, New Jersey! Fled from the southern sun's fierce burning, Back from the chill of the north wind turning, With mayflowers decking her form so rare And magnolias redolent in her hair, Queen Flora rests on thy bosom fair, New Jersey! Lakes the feet of thy mountains are laving, Over thy plains the forests are waving, Across thy meadows and marshes and sands Orchards and farms are clasping their hands, Garden of States in fairest of lands ! New Jersey! Smoke from thy cities' chimneys rising Looms to the sky, a Genius surprising, — A Genius whose touch to new visions gives birth. Of homes rejoicing in music and mirth, And song floating everywhere over the earth, New Jersey! Quaker and Dutchman, long ago meeting, Hailed thy shores with immigrants' greeting, And still on the old home sites to-day Their children's children sturdily stay, Glad for thy progress and leading the way, New Jersey! Mother, dear Mother, thy sons are proclaiming Loyalty; with their banners aflaming The Jersey Blues still march at thy side, Eager to cheer thee with love and with pride, Ready to guard thee, whatever betide. -

A History of Millburn Township »» by Marian Meisner

A History of Millburn Township eBook A History of Millburn Township »» by Marian Meisner Published by Millburn Free Public Library Download-ready Adobe® Acrobat® PDF eBook coming soon! http://www.millburn.lib.nj.us/ebook/main.htm [11/29/2002 12:59:55 PM] content TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Before the Beginning - Millburn in Geological Times II. The First Inhabitants of Millburn III. The Country Before Settlement IV. The First English Settlements in Jersey V. The Indian Deeds VI. The First Millburn Settlers and How They Lived VII. I See by the Papers VIII. The War Comes to Millburn IX. The War Leaves Millburn and Many Loose Ends are Gathered Up X. The Mills of Millburn XI. The Years Between the Revolution and the Coming of the Railroad XII. The Coming of the Railroad XIII. 1857-1870 XIV. The Short Hills and Wyoming Developments XV. The History of Millburn Public Schools XVI. A History of Independent Schools XVII. Millburn's Churches XVIII. Growing Up XIX. Changing Times XX. Millburn Township Becomes a Centenarian XXI. 1958-1976 http://www.millburn.lib.nj.us/ebook/toc.htm [11/29/2002 12:59:58 PM] content Contents CHAPTER I. BEFORE THE BEGINNING Chpt. 1 MILLBURN IN GEOLOGICAL TIMES Chpt. 2 Chpt. 3 The twelve square miles of earth which were bound together on March 20, 1857, by the Legislature of the State of New Jersey, to form a body politic, Chpt. 4 thenceforth to be known as the Township of Millburn, is a fractional part of the Chpt. 5 County of Essex, and a still smaller fragment of the State which gave it birth, Chpt. -

ESSEX County

NJ DEP - Historic Preservation Office Page 1 of 30 New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places Last Update: 9/28/2021 ESSEX County Rose Cottage (ID#3084) ESSEX County 221 Main Street SHPO Opinion: 7/11/1996 Belleville Township Silver Lake Stone Houses (ID#2836) Belleville Fire Department Station #3 (ID#2835) 288-289 and 304 Belmont Avenue, 51 and 57 Heckle Street 136 Franklin Street SHPO Opinion: 9/28/1995 SHPO Opinion: 12/4/1995 745 Washington Avenue (ID#1062) Belleville Public Library (ID#1057) 745 Washington Avenue Corner of Washington Avenue and Academy Street SHPO Opinion: 1/25/1994 SHPO Opinion: 12/3/1976 Bloomfield Township Belleville Municipal Historic District (ID#1058) Washington Avenue between Holmes Street and Bellevue Avenue Arlington Avenue Bridge (ID#254) SHPO Opinion: 4/19/1991 NJ Transit Montclair Line, Milepost 10.54 over Arlington Avenue SHPO Opinion: 2/3/1999 Belleville Park (ID#5676) 398 Mill Street Bakelite Corporation Factory Buildings (ID#2837) SHPO Opinion: 9/6/2018 230 Grove Street SHPO Opinion: 12/4/1995 Branch Brook Park [Historic District] (ID#1216) Bound by Orange Avenue, Newark City Subway (former Morris Canal), Bloomfield Cemetery (ID#5434) Second River, Branch Brook Place, Forest Parkway, and Lake Street 383 Belleville Avenue NR: 1/12/1981 (NR Reference #: 81000392) SR: 4/14/2015 SR: 6/5/1980 Also located in: SHPO Opinion: 3/30/1979 ESSEX County, Glen Ridge Borough Township See Main Entry / Filed Location: ESSEX County, Newark City Bloomfield Junior High School (ID#4250) 177 Franklin Street Essex County Isolation Hospital (ID#629) SHPO Opinion: 8/15/2002 520 Belleville Avenue (at Franklin Avenue) COE: 1/10/1995 Bloomfield Green Historic District (ID#1063) (a.ka. -

Master Plan Reexamination and Update for the Township of Millburn

MASTER PLAN REEXAMINATION AND UPDATE FOR THE TOWNSHIP OF MILLBURN, ESSEX COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Prepared for The Township of Millburn Planning Board by PHILLIPS PREISS GRYGIEL LEHENY HUGHES LLC Planning & Real Estate Consultants Adopted December 19, 2018 FORWARD MILLBURNPROUD PAST, BRIGHT FUTURE PHOTO CREDIT: MARILYN ATLAS-BERNEY Prepared for MASTER PLAN The Township of Millburn Planning Board REEXAMINATION REPORT by Phillips Preiss Grygiel Leheny Hughes LLC Planning & Real Estate Consultants Paul A. Phillips, AICP, PP FOR THE 33-41 Newark Street New Jersey Professional Planner License TOWNSHIP OF MILLBURN, Third Floor, Suite D #3046 ESSEX COUNTY, Hoboken, NJ 07030 NEW JERSEY Elizabeth C. Leheny, AICP, PP Adopted December 19, 2018 New Jersey Professional Planner License #6133 All images PPGLH unless otherwise noted. MASTER PLAN REEXAMINATION AND UPDATE FOR ii THE TOWNSHIP OF MILLBURN, ESSEX COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Acknowledgements PHOTO CREDIT: MARILYN ATLAS-BERNEY Township Committee Planning Board Planning Board Professionals Cheryl H. Burstein Mayor Kenneth Leiby Chairman Edward Buzak, Esq. Attorney Jodi Rosenberg Deputy Mayor Beth Zall Vice Chairwoman Martha Callahan, PE Township Engineer Sam Levy Committeeman Elaine Becker Paul A. Phillips, AICP, PP Planner Dianne Thall-Eglow Committeewoman Miriam Salerno Elizabeth C. Leheny, AICP, PP Planner Jackie Benjamin Lieberberg Committeewoman Daniel Baer Eileen Davitt Zoning Officer/ Roger Manshel Board Secretary Alexander McDonald Business Administrator Joseph Steinberg Christine Gatti, RMC, CMR Township -

Section 3. County Profile

Section 3: County Profile SECTION 3. COUNTY PROFILE This profile describes the general information of the County (physical setting, population and demographics, general building stock, and land use and population trends) and critical facilities located within Morris County. In Section 3, specific profile information is presented and analyzed to develop an understanding of the study area, including the economic, structural, and population assets at risk and the particular concerns that may be present related to hazards analyzed (for example, a high percentage of vulnerable persons in an area). 2020 HMP Changes The “County Profile” is now located in Section 3; previously located in Section 4. It contains updated information regarding the County's physical setting, population and demographics and trends, general building stock, land use and trends, potential new development and critical facilities. This includes U.S. Census ACS 2017 data and additional information regarding the New Jersey Highlands Region in the Development Trends/Future Development subsection. Critical facilities identified as community lifelines using FEMA’s lifeline definition and seven categories were added to the inventory and described in this section. 3.1 GENERAL INFORMATION Morris County is one of the fastest growing counties in the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut metropolitan region. It is located amid rolling hills, broad valleys, and lakes approximately 30 miles northwest of New York City. The County was created by an Act of the State Legislature on March 15, 1738, separating it from Hunterdon County. Morris County was named after Colonel Lewis Morris, then Governor of the Province of New Jersey (the area that now includes Morris, Sussex, and Warren Counties). -

June 2016 Welcome to North Caldwell NORTH CALDWELL Magazine a Social Publication Exclusively for the Residents of North Caldwell

june 2016 Welcome to North Caldwell NORTH CALDWELL magazine A social publication exclusively for the residents of North Caldwell In this issue.. -COVER STORY -North Caldwell Cub Scouts Pinewood Derby Races -BUSINESS SPOTLIGHT K9 Resorts of Fairfield, And as always so much more! NORTH CALDWELL www.n2pub.com DIRECTORY © 2016 Neighborhood Networks Publishing, Inc. 973-226-0800 Police Headquarters AREA DIRECTOR Brian P. O’Neill 973-226-0800 Fire Headquarters [email protected] 973-228-6410 All Borough Offices 101 Administrator Extension EDITOR Becky Clapper 100 Borough Clerk Extension 102 Mayor’s Office Extension WRITERS Kat Krannich 106 Building Permits Extension Joseph Alessi 112 Construction Code Official Extension 109 Municipal Court Extension CREATIVE TEAM Amber Rogerson Allie Leger 107 Engineering Extension Evin Leek Josh Crothers 100 Health/Welfare Extension 101 Planning Board Extension CONTRIBUTORS Cathryn Kessler Maria Rampinelli 100 Board Of Adjustment Extension Bunny Jenkins Jake Wolf 106 Public Works Extension Kat Krannich Jessica Wiederhorn 113 Recreation Extension Chrissy Davenport Teddy Press 106 Recycling Extension Andrea Hecht 111 Tax Assessor Extension 105 Tax Collector Extension NC MAGAZINE Kamni Marsh 100 Trash Collection Extension ASSISTANT PUBLISHER 103 Water Billing Extension 1318 Willowbrook Mall 586 Passaic Ave. Wayne, NJ 07470 West Caldwell, NJ 07006 AD COORDINATOR Melissa Gerrety 973.785.0330 973.226.2726 [email protected] Broadway Square Mall Willowbrook Mall West Caldwell, NJ | 973.226.2726 www.michaelanthonyjewelers.com Wayne, NJ | 973.785.0330 IMPORTANT CONTACTS COVER PHOTO BY: John Paul Endress Firemen’s Community Center 973-228-4060 Tennis Courts 973-228-6433 Municipal Pool 973-228-6434 Board Of Education 973-228-6438 West Essex Regional High School 973-228-1200 Dr.