North Korea: a Geographical Analysis. INSTITUTION Military Academy, West Point, NY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. Bennett C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. -

South Korea Section 3

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

Pdf | 431.24 Kb

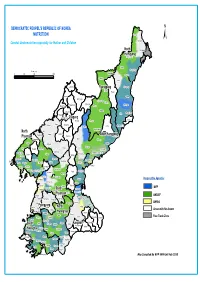

DEMOCRATIC PEOPEL'S REPUBLIC OF KOREA NUTRITION Onsong Kyongwon ± Combat Undernutrition especially for Mother and Children North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Musan Chongjin City Kilometers Taehongdan 050 100 200 Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Kanggye City Chagang Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Responsible Agencies Sunchon City Kowon Sukchon Sinyang Sudong WFP Pyongsong City South Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan UNICEF Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Kangso Sinpyong Popdong UNFPA PyongyangKangnam Thongchon Onchon Junghwa YonsanNorth Kosan Taean Sangwon Areas with No Access Nampo City Hwangju HwanghaeKoksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Free Trade Zone Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City Singye Changdo South Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Kangwon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Jaeryong HwanghaeSonghwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Kangryong Map Compiled By WFP VAM Unit Feb 2010. -

Effective Evangelistic Strategies for North Korean Defectors (Talbukmin) in South Korea

ABSTRACT Effective Evangelistic Strategies for North Korean Defectors (Talbukmin) in South Korea South Korean churches eagerness for spreading the gospel to North Koreans is a passion. However, because of the barriers between the two Koreas, spreading the Good News is nearly impossible. In the middle of the 1990’s, numerous North Koreans defected to China to avoid starvation. Many South Korean missionaries met North Koreans directly and offered the gospel along with necessities for survival in China. Since the early of 2000’s, many Talbukmin have entered South Korea so South Korean churches have directly met North Koreans and spread the gospel. However, the fruits of evangelism are few. South Korean churches find that Talbukmin are very different from South Koreans in large part due to the sixty-year division. South Korean churches do not know or fully understand the characteristics of the Talbukmin. The evangelism strategies and ministry programs of South Korean churches, which are designed for South Koreans, do not adapt well to serve the Talbukmin. This research lists and describes the following five theories to be used in the development of the effective evangelistic strategies for use with the Talbukmin and for use to interpret the interviews and questionnaires: the conversion theory, the contextualization theory, the homogenous principle, the worldview transformation theory, and the Nevius Mission Plan. In the following research exploration of the evangelization of Talbukmin in South Korea occurs through two major research agendas. The first agenda is concerned with the study of the characteristics of Talbukmin to be used for the evangelists’ understanding of the depth of differences. -

Welcome to Korea Day: from Diasporic to Hallyu Fan-Nationalism

International Journal of Communication 13(2019), 3764–3780 1932–8036/20190005 Welcome to Korea Day: From Diasporic to Hallyu Fan-Nationalism IRINA LYAN1 University of Oxford, UK With the increasing appeal of Korean popular culture known as the Korean Wave or hallyu, fans in Israel among Korean studies students have joined—and even replaced— ethnic Koreans in performing nationalism beyond South Korea’s borders, creating what I call hallyu fan-nationalism. As an unintended consequence of hallyu, such nationalism enables non-Korean hallyu fans to take on the empowering roles of cultural experts, educators, and even cultural ambassadors to promote Korea abroad. The symbolic shift from diasporic to hallyu nationalism brings to the fore nonnationalist, nonessentialist, and transcultural perspectives in fandom studies. In tracing the history of Korea Day from the 2000s to the 2010s, I found that hallyu fan-students are mobilized both by the macro mission to promote a positive image of Korea in their home societies and by the micro motivation to repair their own, often stigmatized, self-image. Keywords: transcultural fandom studies, hallyu, Korean Wave, Korean studies, Korea Day, diasporic nationalism While talking with Israeli students enrolled in Korean studies (mostly female fans of Korean popular culture) in an effort to understand their motivations behind organizing Korea Day and promoting Korean culture in Israel in general, I was surprised when some of them used the Hebrew word hasbara, which literally translates as “explanation.” As a synonym for propaganda, hasbara refers to the public diplomacy of Israel that aims to promote a positive image of Israel to the world and to counter its delegitimization. -

China Russia

1 1 1 1 Acheng 3 Lesozavodsk 3 4 4 0 Didao Jixi 5 0 5 Shuangcheng Shangzhi Link? ou ? ? ? ? Hengshan ? 5 SEA OF 5 4 4 Yushu Wuchang OKHOTSK Dehui Mudanjiang Shulan Dalnegorsk Nongan Hailin Jiutai Jishu CHINA Kavalerovo Jilin Jiaohe Changchun RUSSIA Dunhua Uglekamensk HOKKAIDOO Panshi Huadian Tumen Partizansk Sapporo Hunchun Vladivostok Liaoyuan Chaoyang Longjing Yanji Nahodka Meihekou Helong Hunjiang Najin Badaojiang Tong Hua Hyesan Kanggye Aomori Kimchaek AOMORI ? ? 0 AKITA 0 4 DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S 4 REPUBLIC OF KOREA Akita Morioka IWATE SEA O F Pyongyang GULF OF KOREA JAPAN Nampo YAMAJGATAA PAN Yamagata MIYAGI Sendai Haeju Niigata Euijeongbu Chuncheon Bucheon Seoul NIIGATA Weonju Incheon Anyang ISIKAWA ChechonREPUBLIC OF HUKUSIMA Suweon KOREA TOTIGI Cheonan Chungju Toyama Cheongju Kanazawa GUNMA IBARAKI TOYAMA PACIFIC OCEAN Nagano Mito Andong Maebashi Daejeon Fukui NAGANO Kunsan Daegu Pohang HUKUI SAITAMA Taegu YAMANASI TOOKYOO YELLOW Ulsan Tottori GIFU Tokyo Matsue Gifu Kofu Chiba SEA TOTTORI Kawasaki KANAGAWA Kwangju Masan KYOOTO Yokohama Pusan SIMANE Nagoya KANAGAWA TIBA ? HYOOGO Kyoto SIGA SIZUOKA ? 5 Suncheon Chinhae 5 3 Otsu AITI 3 OKAYAMA Kobe Nara Shizuoka Yeosu HIROSIMA Okayama Tsu KAGAWA HYOOGO Hiroshima OOSAKA Osaka MIE YAMAGUTI OOSAKA Yamaguchi Takamatsu WAKAYAMA NARA JAPAN Tokushima Wakayama TOKUSIMA Matsuyama National Capital Fukuoka HUKUOKA WAKAYAMA Jeju EHIME Provincial Capital Cheju Oita Kochi SAGA KOOTI City, town EAST CHINA Saga OOITA Major Airport SEA NAGASAKI Kumamoto Roads Nagasaki KUMAMOTO Railroad Lake MIYAZAKI River, lake JAPAN KAGOSIMA Miyazaki International Boundary Provincial Boundary Kagoshima 0 12.5 25 50 75 100 Kilometers Miles 0 10 20 40 60 80 ? ? ? ? 0 5 0 5 3 3 4 4 1 1 1 1 The boundaries and names show n and t he designations us ed on this map do not imply of ficial endors ement or acceptance by the United N at ions. -

DPRK/North Hamgyong Province: Floods

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) DPRK/North Hamgyong Province: Floods Emergency Appeal n° MDRKP008 Glide n° FL-2016-000097-PRK Date of issue: 20 September 2016 Date of disaster: 31 August 2016 Operation manager (responsible for this EPoA): Point of contact: Marlene Fiedler Pak Un Suk Disaster Risk Management Delegate Emergency Relief Coordinator IFRC DPRK Country Office DPRK Red Cross Society Operation start date: 2 September 2016 Operation end date (timeframe): 31 August 2017 (12 months) Overall operation budget: CHF 15,199,723 DREF allocation: CHF 506,810 Number of people affected: Number of people to be assisted: 600,000 people Direct: 28,000 people (7,000 families); Indirect: more than 163,000 people in Hoeryong City, Musan County and Yonsa County Host National Society(ies) presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: The State Committee for Emergency and Disaster Management (SCEDM), UN Organizations, European Union Programme Support Units A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster From August 29th to August 31st heavy rainfall occurred in North Hamgyong Province, DPRK – in some areas more than 300 mm of rain were reported in just two days, causing the flooding of the Tumen River and its tributaries around the Chinese-DPRK border and other areas in the province. Within a particularly intense time period of four hours in the night between 30 and 31 August 2016, the waters of the river Tumen rose between six and 12 metres, causing an immediate threat to the lives of people in nearby villages. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:21/01/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: AN 1: JONG 2: HYUK 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Diplomat DOB: 14/03/1970. a.k.a: AN, Jong, Hyok Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) Passport Details: 563410155 Address: Egypt.Position: Diplomat DPRK Embassy Egypt Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0001 Date designated on UK Sanctions List: 31/12/2020 (Further Identifiying Information):Associations with Green Pine Corporation and DPRK Embassy Egypt (UK Statement of Reasons):Representative of Saeng Pil Trading Corporation, an alias of Green Pine Associated Corporation, and DPRK diplomat in Egypt.Green Pine has been designated by the UN for activities including breach of the UN arms embargo.An Jong Hyuk was authorised to conduct all types of business on behalf of Saeng Pil, including signing and implementing contracts and banking business.The company specialises in the construction of naval vessels and the design, fabrication and installation of electronic communication and marine navigation equipment. (Gender):Male Listed on: 22/01/2018 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13590. 2. Name 6: BONG 1: PAEK 2: SE 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 21/03/1938. Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea Position: Former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee,Former member of the National Defense Commission,Former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0251 (UN Ref): KPi.048 (Further Identifiying Information):Paek Se Bong is a former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee, a former member of the National Defense Commission, and a former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Listed on: 05/06/2017 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13478. -

Detailed Species Accounts from The

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

Inter-Korean Maritime Dynamics in the Northeast Asian Context César Ducruet, Stanislas Roussin

Inter-Korean maritime dynamics in the Northeast Asian context César Ducruet, Stanislas Roussin To cite this version: César Ducruet, Stanislas Roussin. Inter-Korean maritime dynamics in the Northeast Asian context: Peninsular integration or North Korea’s pragmatism?. North / South Interfaces in the Korean Penin- sula, Dec 2008, Paris, France. halshs-00463620 HAL Id: halshs-00463620 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00463620 Submitted on 13 Mar 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Inter-Korean Maritime Dynamics in the Northeast Asian Context Peninsular Integration or North Korea’s Pragmatism? Draft paper International Workshop on “North / South Interfaces in the Korean Peninsula” EHESS, Paris, December 17-19, 2008 César DUCRUET1 Stanislas ROUSSIN Centre National de la Recherche General Manager & Head of Scientifique (CNRS) Research Department UMR 8504 Géographie-cités / SERIC COREE Equipe P.A.R.I.S. 1302 Byucksan Digital Valley V 13 rue du Four 60-73 Gasan-dong, Geumcheon-gu F-75006 Paris Seoul 153-801 France Republic of Korea Tel. +33 (0)140-464-000 Tel: +82 (0)2-2082-5613 Fax +33(0)140-464-009 Fax: +82 (0)2-2082-5616 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Abstract. -

25 Interagency Map Pmedequipment.Mxd

Onsong Kyongwon North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Provision of Medical Equipment Musan Chongjin City Taehongdan Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Chagang Kanggye City Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Responsible Agency Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon WHO Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City UNFPA Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon UNICEF Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon IFRC Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan EUPS 1 Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Sunchon City Kowon EUPS 3 Sukchon SouthSinyang Sudong Pyongsong City Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon EUPS 7 PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Free Trade Zone Kangso Sinpyong Popdong PyongyangKangnam North Thongchon Onchon Junghwa Yonsan Kosan Taean Sangwon No Access Allowed Nampo City Hwanghae Hwangju Koksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City South Singye Kangwon Changdo Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Hwanghae Jaeryong Songhwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Map compliled by VAM Unit Kangryong WFP DPRK Feb 2010. -

A Brief of the Korea History

A Brief of the Korea History Chronicle of Korea BC2333- BC.238- 918- 1392- 1910- BC57-668 668-918 1945- BC 108 BC1st 1392 1910 1945 Nangrang Dae GoGuRyeo BukBuYeo Unified GoRyeo JoSun Japan- Han DongBuYeo BaekJae Silla Invaded Min JolBonBuYe Silla BalHae Gug o GaRa (R.O.K DongOkJeo (GaYa) Yo Myng Korea) GoJoSun NamOkJeo Kum Chung (古朝鮮) BukOkJeo WiMan Won Han-5- CHINA Gun SamHan (Wae) (Wae) (IlBon) (IlBon) (IlBon) (Wae) (JAPAN) 1 한국역사 연대기 BC2333- BC.238- BC1세기- 918- 1392- 1910- 668-918 1945- BC 238 BC1세기 668 1392 1910 1945 낙 랑 국 북 부 여 고구려 신 라 고 려 조선 일제강 대한민 동 부 여 신 라 발 해 요 명 점기 국 졸본부여 백 제 금 청 동 옥 저 고조선 가 라 원 중국 남 옥 저 (古朝鮮) (가야) 북 옥 저 위 만 국 한 5 군 (왜) (왜) (일본) (일본) (일본) (일본) 삼 한 (왜) 국가계보 대강 (II) BC108 918 BC2333 BC194 BC57 668 1392 1910 1945 고구려 신 라 고조선(古朝鮮) 부여 옥저 대한 백 제 동예 고려 조선 민국 BC18 660 2 3 1 GoJoSun(2333BC-108BC) 2 Three Kingdom(57BC-AD668) 3 Unified Shilla(668-935) / Balhae 4 GoRyeo(918-1392) 5 JoSun(1392-1910) 6 Japan Colony(1910-1945) 7 The Division of Korea 8 Korea War(1950-1953) 9 Economic Boom In South Korea 1. GoJoSun [고조선] (2333BC-108BC) the origin of Korea n According to the Dangun creation mythological Origin n Dangun WangGeom establish the old JoSun in Manchuria. n The national idea of Korea is based on “Hong-ik-in-gan (弘益人間)”, Devotion the welfare of world-wide human being n DanGun JoSun : 48 DanGuns(Kings) + GiJa JoSun + WeeMan JoSun 4 “고조선의 강역을 밝힌다”의 고조선 강역 - 저자: 윤내현교수, 박선희교수, 하문식교수 5 Where is Manchuria 2.