9751810 Published Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Tuesday, 12 September 2006 (Extract from book 12) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor Professor DAVID de KRETSER, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Environment, Minister for Water and Minister for Victorian Communities.............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Finance, Minister for Major Projects and Minister for WorkCover and the TAC............................ The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Education Services and Minister for Employment and Youth Affairs................................................. The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Transport............................................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Housing.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Innovation and Minister for State and Regional Development......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Agriculture........................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................ The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Community Services and Minister for Children............ The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, -

House of Representatives By-Elections 1902-2002

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 15 2002–03 House of Representatives By-elections 1901–2002 DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1440-2009 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 15 2002–03 House of Representatives By-elections 1901–2002 Gerard Newman, Statistics Group Scott Bennett, Politics and Public Administration Group 3 March 2003 Acknowledgments The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Murray Goot, Martin Lumb, Geoff Winter, Jan Pearson, Janet Wilson and Diane Hynes in producing this paper. -

The Legacy of Robert Menzies in the Liberal Party of Australia

PASSING BY: THE LEGACY OF ROBERT MENZIES IN THE LIBERAL PARTY OF AUSTRALIA A study of John Gorton, Malcolm Fraser and John Howard Sophie Ellen Rose 2012 'A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of BA (Hons) in History, University of Sydney'. 1 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to acknowledge the guidance of my supervisor, Dr. James Curran. Your wisdom and insight into the issues I was considering in my thesis was invaluable. Thank you for your advice and support, not only in my honours’ year but also throughout the course of my degree. Your teaching and clear passion for Australian political history has inspired me to pursue a career in politics. Thank you to Nicholas Eckstein, the 2012 history honours coordinator. Your remarkable empathy, understanding and good advice throughout the year was very much appreciated. I would also like to acknowledge the library staff at the National Library of Australia in Canberra, who enthusiastically and tirelessly assisted me in my collection of sources. Thank you for finding so many boxes for me on such short notice. Thank you to the Aspinall Family for welcoming me into your home and supporting me in the final stages of my thesis and to my housemates, Meg MacCallum and Emma Thompson. Thank you to my family and my friends at church. Thank you also to Daniel Ward for your unwavering support and for bearing with me through the challenging times. Finally, thanks be to God for sustaining me through a year in which I faced many difficulties and for providing me with the support that I needed. -

Defence Policy-Making

Chapter 1 The Road to Russell A career in the Public Service which closed after a decade as Secretary to the Department of Defence started from what might seem an unlikely origin. In 1942, aged 28, I was brought to Canberra from a wartime reserved occupation to work on analysing Australia's interests in the international economic and financial regulations being proposed for Australia's responses by the British and American planners who were preparing for a better world system after the war had been won. For a short period I was made responsible to Dr Roland Wilson (later Secretary to the Treasury), but in 1943 the Labor Government created the Department of Post-War Reconstruction, with J.B. Chifley as its Minister (and concurrently Treasurer) and Dr H.C. `Nugget' Coombs as its Director-General. I worked under Coombs for several years, preparing papers and advice for several of Australia's most senior economists on the problems to be expected, and the safeguards needed, to protect Australia in the impact of these post-war plans of the two major economic powers. Over the years, I attended several international conferences arranged to discuss and to amend and endorse these plans, beginning with the 1944 Bretton Woods International Monetary Conference. External Affairs 1945 I was seconded into the Department of External Affairs in 1945. That Department, under the urging of Dr J.W. Burton, was seeking a role in policy in these economic fields, particularly with the prospect of the United Nations and other institutions being set up with various regulatory powers. -

Inside the Canberra Press Gallery: Life in the Wedding Cake of Old

INSIDE the CANBERRA PRESS GALLERY Life in the Wedding Cake of Old Parliament House INSIDE the CANBERRA PRESS GALLERY Life in the Wedding Cake of Old Parliament House Rob Chalmers Edited by Sam Vincent and John Wanna THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Chalmers, Rob, 1929-2011 Title: Inside the Canberra press gallery : life in the wedding cake of Old Parliament House / Rob Chalmers ; edited by Sam Vincent and John Wanna. ISBN: 9781921862366 (pbk.) 9781921862373 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Australia. Parliament--Reporters and Government and the press--Australia. Journalism--Political aspects-- Press and politics--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Vincent, Sam. Wanna, John. Dewey Number: 070.4493240994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Back cover image courtesy of Heide Smith Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Foreword . ix Preface . xi 1 . Youth . 1 2 . A Journo in Sydney . 9 3 . Inside the Canberra Press Gallery . 17 4 . Menzies: The giant of Australian politics . 35 5 . Ming’s Men . 53 6 . Parliament Disgraced by its Members . 71 7 . Booze, Sex and God . -

Judges and Retirement Ages

JUDGES AND RETIREMENT AGES ALYSIA B LACKHAM* All Commonwealth, state and territory judges in Australia are subject to mandatory retirement ages. While the 1977 referendum, which introduced judicial retirement ages for the Australian federal judiciary, commanded broad public support, this article argues that the aims of judicial retirement ages are no longer valid in a modern society. Judicial retirement ages may be causing undue expense to the public purse and depriving the judiciary of skilled adjudicators. They are also contrary to contemporary notions of age equality. Therefore, demographic change warrants a reconsideration of s 72 of the Constitution and other statutes setting judicial retirement ages. This article sets out three alternatives to the current system of judicial retirement ages. It concludes that the best option is to remove age-based limitations on judicial tenure. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 739 II Judicial Retirement Ages in Australia ................................................................... 740 A Federal Judiciary .......................................................................................... 740 B Australian States and Territories ............................................................... 745 III Criticism of Judicial Retirement Ages ................................................................... 752 A Critiques of Arguments in Favour of Retirement Ages ........................ -

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-Funded Flights Taken by Former Mps and Their Widows Between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed in Descending Order by Number of Flights Taken

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-funded flights taken by former MPs and their widows between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed in descending order by number of flights taken NAME PARTY No OF COST $ FREQUENT FLYER $ SAVED LAST YEAR IN No OF YEARS IN FLIGHTS FLIGHTS PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENT Ian Sinclair Nat, NSW 701 $214,545.36* 1998 25 Margaret Reynolds ALP, Qld 427 $142,863.08 2 $1,137.22 1999 17 Gordon Bilney ALP, SA 362 $155,910.85 1996 13 Barry Jones ALP, Vic 361 $148,430.11 1998 21 Graeme Campbell ALP/Ind, WA 350 $132,387.40 1998 19 Noel Hicks Nat, NSW 336 $99,668.10 1998 19 Dr Michael Wooldridge Lib, Vic 326 $144,661.03 2001 15 Fr Michael Tate ALP, Tas 309 $100,084.02 11 $6,211.37 1993 15 Frederick M Chaney Lib, WA 303 $195,450.75 19 $16,343.46 1993 20 Tim Fischer Nat, NSW 289 $99,791.53 3 $1,485.57 2001 17 John Dawkins ALP, WA 271 $142,051.64 1994 20 Wallace Fife Lib, NSW 269 $72,215.48 1993 18 Michael Townley Lib/Ind, Tas 264 $91,397.09 1987 17 John Moore Lib, Qld 253 $131,099.83 2001 26 Al Grassby ALP, NSW 243 $53,438.41 1974 5 Alan Griffiths ALP, Vic 243 $127,487.54 1996 13 Peter Rae Lib, Tas 240 $70,909.11 1986 18 Daniel Thomas McVeigh Nat, Qld 221 $96,165.02 1988 16 Neil Brown Lib, Vic 214 $99,159.59 1991 17 Jocelyn Newman Lib, Tas 214 $67,255.15 2002 16 Chris Schacht ALP, SA 214 $91,199.03 2002 15 Neal Blewett ALP, SA 213 $92,770.32 1994 17 Sue West ALP, NSW 213 $52,870.18 2002 16 Bruce Lloyd Nat, Vic 207 $82,158.02 7 $2,320.21 1996 25 Doug Anthony Nat, NSW 204 $62,020.38 1984 27 Maxwell Burr Lib, Tas 202 $55,751.17 1993 18 Peter Drummond -

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-Four

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-four Proceedings of the Twenty-fourth Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Traders Hotel Brisbane, 159 Roma Street, Hobart — August 2012 © Copyright 2014 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Contents Introduction Julian Leeser The Fourth Sir Harry Gibbs Memorial Oration Senator the Honourable George Brandis In Defence of Freedom of Speech Chapter One The Honourable Ian Callinan Defamation, Privacy, the Finkelstein Report and the Regulation of the Media Chapter Two Michael Sexton Flights of Fancy: The Implied Freedom of Political Communication 20 Years On Chapter Three The Honourable Justice J. D. Heydon Sir Samuel Griffith and the Making of the Australian Constitution Chapter Four The Honourable Christian Porter Federal-State Relations and the Changing Economy Chapter Five The Honourable Richard Court A Federalist Agenda for Coast to Coast Liberal (or Labor) Governments Chapter Six Keith Kendall The Case for a State Income Tax Chapter Seven Josephine Kelly The Constitutionality of the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act i Chapter Eight The Honourable Gary Johns Native Title 20 Years On: Beyond the Hyperbole Chapter Nine Lorraine Finlay Indigenous Recognition – Some Issues Chapter Ten J. B. Paul Speaker of the House Contributors ii Introduction Julian Leeser The 24th Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society was held in Brisbane during the weekend of 17-19 August 2012. It marked the 20th anniversary of the Society’s birth. 1992 was undoubtedly a momentous year in Australia’s constitutional history. On 2 January 1992 the perspicacious John and Nancy Stone decided to incorporate the Samuel Griffith Society thirteen days after Paul Keating was appointed Prime Minister. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Tuesday, 2 September 2014 (Extract from book 12) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable ALEX CHERNOV, AC, QC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry (from 17 March 2014) Premier, Minister for Regional Cities and Minister for Racing .......... The Hon. D. V. Napthine, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for State Development, and Minister for Regional and Rural Development ................................ The Hon. P. J. Ryan, MP Treasurer ....................................................... The Hon. M. A. O’Brien, MP Minister for Innovation, Minister for Tourism and Major Events, and Minister for Employment and Trade .............................. The Hon. Louise Asher, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs ...... The Hon. T. O. Bull, MP Attorney-General, Minister for Finance and Minister for Industrial Relations ..................................................... The Hon. R. W. Clark, MP Minister for Health and Minister for Ageing .......................... The Hon. D. M. Davis, MLC Minister for Education ............................................ The Hon. M. F. Dixon, MP Minister for Sport and Recreation, and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs .... The Hon. D. K. Drum, MLC Minister for Planning, and Minister for Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship .................................................. -

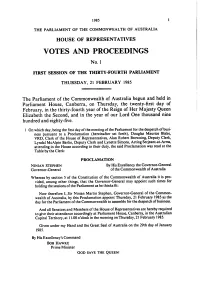

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1985 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-FOURTH PARLIAMENT THURSDAY, 21 FEBRUARY 1985 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Thursday, the twenty-first day of February, in the thirty-fourth year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and eighty-five. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of busi- ness pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Douglas Maurice Blake, VRD, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Alan Robert Browning, Deputy Clerk, Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Deputy Clerk and Lynette Simons, Acting Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION NINIAN STEPHEN By His Excellency the Governor-General Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Whereas by section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia it is pro- vided, among other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now therefore I, Sir Ninian Martin Stephen, Governor-General of the Common- wealth of Australia, by this Proclamation appoint Thursday, 21 February 1985 as the day for the Parliament of the Commonwealth to assemble for the despatch of business. And all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly at Parliament House, Canberra, in the Australian Capital Territory, at 11.00 o'clock in the morning on Thursday, 21 February 1985. -

House of Representatives

1962. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. No. 1. FIRST SESSION OF THE TWENTY-FOURTH PARLIAMENT. TUESDAY, 20TH FEBRUARY, 1962. The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the twentieth day of February, in the eleventh year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and sixty-two. 1. On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Alan George Turner, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Norman James Parkes, Clerk Assistant, John Athol Pettifer, Second Clerk Assistant, and Alan Robert Browning, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk:- PROCLAMATION Commonwealth of By His Excellency the Governor-General in and over the Commonwealth Australia to wit. of Australia. DE L'ISLE Governor-General. W HEREAS by the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia it is amongst other things provided that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the Sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now THEREFORE I, WILLIAM PHIIP, VISCOUNT DE L'IsLs, the Governor-General aforesaid, in the exercise of the power conferred by the said Constitution, do by this my Proclamation appoint Tuesday, the twentieth day of February, One thousand nine hundred and sixty-two, as the day for the said Parliament to assemble and be holden for the despatch of divers urgent and important affairs: and all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give attendance accordingly in the building known as Parliament House, Canberra, at the hour of ten-thirty o'clock in the morning on the said twentieth day of February, One thousand nine hundred and sixty-two. -

House of Representatives

1964. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. No. 1. FIRST SESSION OF THE TWENTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT. TUESDAY, 25TH FEBRUARY, 1964. The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the twenty-fifth day of February, in the thirteenth year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and sixty-four. 1. On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Alan George Turner, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Norman James Parkes, Clerk Assistant, John Athol Pettifer, Second Clerk Assistant, and Alan Robert Browning, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk:- PROCLAMATION Commonwealth of By His Excellency the Governor.General in and over the Commonwealth Australia to wit. of Australia. DE L'ISLE Governor-General. HEREAS by the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia it is amongst other things provided that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the Sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now THEREFORE I, WILLIAM PHILIP, VISCOUNT DE L'IsLIB, the Governor-General aforesaid, in the exercise of the power conferred by the said Constitution, do by Ihis my Proclamation appoint Tuesday, the twenty-fifth day of February, One thousand nine hundred and sixty-four, as the day for the said Parliament to assemble and be holden for the despatch of divers urgent and important affairs: and all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give attendance accordingly in the building known as Parliament House, Canberra, at the hour of eleven o'clock in the morning on the said twenty-fifth day of February, One thousand nine hundred and sixty-four.