Download for the Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moscow Grand Prix 2017

Moscow Grand Prix 2017 Moscow (Russia), DRUZHBA, Sports Complex 17-19.02.2017 Спорт вокруг. Alina Kabaeva CHAMPIONS CUP – GAZPROM (Grand Prix Qualifications – within the framework of ‘Gazprom for Children’ Program) 2017 Moscow R. G. Grand Prix 17.02.2017 - 18.02.2017 Moscow Grand Prix 2017 Qualification. START LIST 17.02.2017 19:00 20:00 1 stream 1 Filiorianu Anna Luiza Romania 20307 1 15 2 Tashkenbaeva Sabina Uzbekistan 23538 2 16 3 Gamalejeva Jelizaveta Latvia 14769 3 17 4 Ruprecht Nicol Austria 5727 4 18 5 Soldatova Aleksandra Russia 20096 5 19 6 Kabrits Laurabel Estonia 20281 6 20 7 Gergalo Rebecca Finland 22567 7 21 8 Halkina Katsiaryna Belarus 8861 8 22 9 Agagulian Iasmina Armenia 35527 9 23 10 Ormrod Zoe Australia 18356 10 24 11 Kratochwill Spela Slovenia 9540 11 25 12 Averina Dina Russia 18528 12 26 13 Veinberg Filanovsky Victoria Israel 15247 13 27 14 Sherlock Stephani Great Britain 18795 14 28 20:00 21:00 2 stream 1 Lindgren Petra Sweden 10551 1 14 2 Bravikova Yulia Russia 18532 2 15 3 Agiurgiuculese Alexandra Italy 32232 3 16 4 Nemeckova Daniela Czech Republic 29518 4 17 5 Ashram Linoy Israel 22468 5 18 6 Proncenko Veronika Lithuania 20584 6 19 7 Averina Arina Russia 18527 7 20 8 Sebkova Anna Czech Republic 10471 8 21 9 Jovenin Axelle France 29499 9 22 10 Kim Chaewoon Korea 28673 10 23 11 Vladinova Neviana Bulgaria 22769 11 24 12 Kilianova Xenia Slovakia 15177 12 25 13 Ashirbayeva Sabina Kazakhstan 18531 13 26 1 / 2 GymRytm’2000 Alina Kabaeva CHAMPIONS CUP – GAZPROM (Grand Prix Qualifications – within the framework of ‘Gazprom for Children’ Program) 2017 Moscow R. -

International Sales Autumn 2017 Tv Shows

INTERNATIONAL SALES AUTUMN 2017 TV SHOWS DOCS FEATURE FILMS THINK GLOBAL, LIVE ITALIAN KIDS&TEEN David Bogi Head of International Distribution Alessandra Sottile Margherita Zocaro Cristina Cavaliere Lucetta Lanfranchi Federica Pazzano FORMATS Marketing and Business Development [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mob. +39 3351332189 Mob. +39 3357557907 Mob. +39 3334481036 Mob. +39 3386910519 Mob. +39 3356049456 INDEX INDEX ... And It’s Snowing Outside! 108 As My Father 178 Of Marina Abramovic 157 100 Metres From Paradise 114 As White As Milk, As Red As Blood 94 Border 86 Adriano Olivetti And The Letter 22 46 Assault (The) 66 Borsellino, The 57 Days 68 A Case of Conscience 25 At War for Love 75 Boss In The Kitchen (A) 112 A Good Season 23 Away From Me 111 Boundary (The) 50 Alex&Co 195 Back Home 12 Boyfriend For My Wife (A) 107 Alive Or Preferably Dead 129 Balancing Act (The) 95 Bright Flight 101 All The Girls Want Him 86 Balia 126 Broken Years: The Chief Inspector (The) 47 All The Music Of The Heart 31 Bandit’s Master (The) 53 Broken Years: The Engineer (The) 48 Allonsanfan 134 Bar Sport 118 Broken Years: The Magistrate (The) 48 American Girl 42 Bastards Of Pizzofalcone (The) 15 Bruno And Gina 168 Andrea Camilleri: The Wild Maestro 157 Bawdy Houses 175 Bulletproof Heart (A) 1, 2 18 Angel of Sarajevo (The) 44 Beachcombers 30 Bullying Lesson 176 Anija 173 Beauty And The Beast (The) 54 Call For A Clue 187 Anna 82 Big Racket (The) -

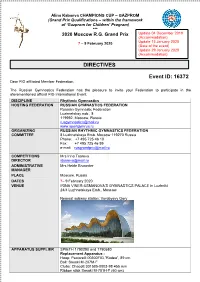

Event ID: 16372 DIRECTIVES

Alina Kabaeva CHAMPIONS CUP – GAZPROM (Grand Prix Qualifications – within the framework of ‘Gazprom for Children’ Program) *** 2020 Moscow R.G. Grand Prix Update 04 December 2019 (Accommodation) 7 – 9 February 2020 Update 15 January 2020 (Date of the event) Update 29 January 2020 (Accommodation) DIRECTIVES Event ID: 16372 Dear FIG affiliated Member Federation, The Russian Gymnastics Federation has the pleasure to invite your Federation to participate in the aforementioned official FIG International Event. DISCIPLINE Rhythmic Gymnastics HOSTING FEDERATION RUSSIAN GYMNASTICS FEDERATION Russian Gymnastic Federation Luzhnetskay nab., 8 119992, Moscow, Russia [email protected] www.sportgymrus.ru ORGANIZING RUSSIAN RHYTHMIC GYMNASTICS FEDERATION COMMITTEE 8 Luzhnetskaya Emb. Mocsow 119270 Russia Phone: +7 495 725 46 10 Fax: +7 495 725 46 99 e-mail: [email protected] COMPETITIONS Mrs Irina Tsareva DIRECTOR [email protected] ADMINISTRATIVE Mrs Heide Bruneder MANAGER PLACE Moscow, Russia DATES 7– 9 February 2020 VENUE IRINA VINER-USMANOVA’S GYMNASTICS PALACE in Luzhniki 24/4 Luzhnetskaya Emb., Moscow Nearest subway station: Vorobyevy Gory APPARATUS SUPPLIER SPIETH 1790290 and 1790580 Replacement Apparatus : Hoop: Pastorelli 00300FIG,”Rodeo”, 89 cm Ball: Sasaki M-207M-F Clubs: Chacott 301505-0003-98 455 mm Ribbon stick Sasaki M-781H-F (60 cm) Ribbon – Chacott 301500-0090-98 (6m) RULES The event will be organized under the following FIG rules, as valid in the year of the event, except for any deviation mentioned in these directives: • Statutes -

The Montgazette | March 2021

Pederson & Wentz “Sound of Metal” Music Programs A team in turmoil, Page 14 A film review,Page 17 And the pandemic, Page 11 a student publication FREE Issue 85 Serving Montgomery County Community College and the Surrounding Community March 2021 “Insurrection at the Capitol” Read on Page 7. Photo by Pixabay.com Page 2 THE MONTGAZETTE March 2021 The Staff Josh Young Editor-in-Chief Sufyan Davis-Arrington Michael Chiodo Emma Daubert Alaysha Gladden Amanda Hadad Daniel Johnson The unexpected positives of the COVID pandemic Nina Lima Kylah McNamee Lauren Meter Josh Young Audrey Schippnick The Montgazette Editor-in-Chief Krystyna Ursta Nicholas Young March Contributors Hello, and welcome back to to our busy schedules. Luckily, physically active. According Most importantly, however, Yaniv Aronson everyone who has returned to their this particular prediction came to a study published in the students have learned just Robin Bonner Advisors studies at Montgomery County true for me, for the most part; International Journal of how resilient they really are. Community College. I hope you however, since that letter, there Environmental Research and We, as students, have been Joshua Woodroffe Design & Layout all have a positive, successful have been many other positives Public Health that examined forced to adapt on the fly in an semester. As always, I am happy to come out of this less-than- Belgian adults, of people who environment of almost constant to extend a warm welcome to ideal situation. were classified as “low active” uncertainty, resulting in frequent students who are entering their In addition to spending (getting little to no exercise), battles with adversity, while also first semester at the College. -

How America Lost Its Mind the Nation’S Current Post-Truth Moment Is the Ultimate Expression of Mind-Sets That Have Made America Exceptional Throughout Its History

1 How America Lost Its Mind The nation’s current post-truth moment is the ultimate expression of mind-sets that have made America exceptional throughout its history. KURT ANDERSEN SEPTEMBER 2017 ISSUE THE ATLANTIC “You are entitled to your own opinion, but you are not entitled to your own facts.” — Daniel Patrick Moynihan “We risk being the first people in history to have been able to make their illusions so vivid, so persuasive, so ‘realistic’ that they can live in them.” — Daniel J. Boorstin, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America (1961) 1) WHEN DID AMERICA become untethered from reality? I first noticed our national lurch toward fantasy in 2004, after President George W. Bush’s political mastermind, Karl Rove, came up with the remarkable phrase reality-based community. People in “the reality-based community,” he told a reporter, “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality … That’s not the way the world really works anymore.” A year later, The Colbert Report went on the air. In the first few minutes of the first episode, Stephen Colbert, playing his right-wing-populist commentator character, performed a feature called “The Word.” His first selection: truthiness. “Now, I’m sure some of the ‘word police,’ the ‘wordinistas’ over at Webster’s, are gonna say, ‘Hey, that’s not a word!’ Well, anybody who knows me knows that I’m no fan of dictionaries or reference books. They’re elitist. Constantly telling us what is or isn’t true. Or what did or didn’t happen. -

Articles & Reports

1 Reading & Resource List on Information Literacy Articles & Reports Adegoke, Yemisi. "Like. Share. Kill.: Nigerian police say false information on Facebook is killing people." BBC News. Accessed November 21, 2018. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt- sh/nigeria_fake_news. See how Facebook posts are fueling ethnic violence. ALA Public Programs Office. “News: Fake News: A Library Resource Round-Up.” American Library Association. February 23, 2017. http://www.programminglibrarian.org/articles/fake-news-library-round. ALA Public Programs Office. “Post-Truth: Fake News and a New Era of Information Literacy.” American Library Association. Accessed March 2, 2017. http://www.programminglibrarian.org/learn/post-truth- fake-news-and-new-era-information-literacy. This has a 45-minute webinar by Dr. Nicole A. Cook, University of Illinois School of Information Sciences, which is intended for librarians but is an excellent introduction to fake news. Albright, Jonathan. “The Micro-Propaganda Machine.” Medium. November 4, 2018. https://medium.com/s/the-micro-propaganda-machine/. In a three-part series, Albright critically examines the role of Facebook in spreading lies and propaganda. Allen, Mike. “Machine learning can’g flag false news, new studies show.” Axios. October 15, 2019. ios.com/machine-learning-cant-flag-false-news-55aeb82e-bcbb-4d5c-bfda-1af84c77003b.html. Allsop, Jon. "After 10,000 'false or misleading claims,' are we any better at calling out Trump's lies?" Columbia Journalism Review. April 30, 2019. https://www.cjr.org/the_media_today/trump_fact- check_washington_post.php. Allsop, Jon. “Our polluted information ecosystem.” Columbia Journalism Review. December 11, 2019. https://www.cjr.org/the_media_today/cjr_disinformation_conference.php. Amazeen, Michelle A. -

Unified Conspiracy Theory - Rationalwiki

Unified Conspiracy Theory - RationalWiki http://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Unified_Conspiracy_Theory Unified Conspiracy Theory From RationalWiki The Unified Conspiracy Theory is a conspiracy theory, popular with Some dare call it some paranoids, that all of reality is controlled by a single evil entity that has it in for them. It can be a political entity, like "The Illuminati", or a Conspiracy metaphysical entity, like Satan, but this entity is responsible for the creation and management of everything bad. The Church of the SubGenius has adopted this notion as fundamental dogma. Michael Barkun coined the term "superconspiracy" to refer the idea that the world is controlled by an interlocking hierarchy of conspiracies. Secrets revealed! Similarly, Michael Kelly, a neoconservative journalist, coined the term America Under Siege "fusion paranoia" in 1995 to refer to the blending of conspiracy theories CW Leonis of the left with those of the right into a unified conspiratorial Doug Rokke [1] worldview. Guillotine List of conspiracy theories This was played with in the Umberto Eco novel Foucault's Pendulum , in Majestic 12 which the characters make up a conspiracy theory like this...except it Pravda.ru turns out to be true. Shakespeare authorship Society of Jesus Tupac Shakur Contents v - t - e (http://rationalwiki.org /w/index.php?title=Template:Conspiracynav& action=edit) 1 See also 1.1 (In)Famous proponents 2 External links 3 Footnotes See also List of Conspiracy Theories Maltheism Crank magnetism (In)Famous proponents David Icke Alex Jones Lyndon LaRouche Jeff Rense 1 of 2 7/19/2012 8:24 PM Unified Conspiracy Theory - RationalWiki http://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Unified_Conspiracy_Theory External links Flowchart guide to the grand conspiracy (http://farm4.static.flickr.com /3048/2983450505_34b4504302_o.png) Conspiracy Kitchen Sink (http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/ConspiracyKitchenSink) , TV Tropes Footnotes 1. -

Vegas PBS Source, Volume No

Trusted. Valued. Essential. SEPTEMBER 2019 Vegas PBS A Message from the Management Team General Manager General Manager Tom Axtell, Vegas PBS Educational Media Services Director Niki Bates Production Services Director Kareem Hatcher Business Manager Brandon Merrill Communications and Brand Management Director Allison Monette Content Director Explore a True American Cyndy Robbins Workforce Training & Economic Development Director Art Form in Country Music Debra Solt Interim Director of Development and Strategic Relations en Burns is television’s most prolific documentarian, and PBS is the Clark Dumont exclusive home he has chosen for his work. Member donations make it Engineering, IT and Emergency Response Director possible for us to devote enough research and broadcast time to explore John Turner the facts, nuances and impact of history in our daily lives and our shared SOUTHERN NEVADA PUBLIC TELEVISION BOARD OF DIRECTORS American values. Since his first film in 1981, Ken Burns has been telling Executive Director Kunique and fascinating stories of the United States. Tom Axtell, Vegas PBS Ken has provided historical insights on events like The Civil War, Prohibition and President The Vietnam War. He has investigated the impact of important personalities in The Tom Warden, The Howard Hughes Corporation Roosevelts, Thomas Jefferson and Mark Twain, and signature legacies like The Vice President Brooklyn Bridge,The National Parks and The Statute of Liberty. Now the filmmaker Clark Dumont, Dumont Communications, LLC explores another thread of the American identity in Country Music. Beginning Sunday, Secretary September 15 at 8 p.m., step back in time and explore the remarkable stories of the Nora Luna, UNR Cooperative Extension people and places behind this true American art form in eight two-hour segments. -

Friday, December 7, 2018

Friday, December 7, 2018 Registration Desk Hours: 7:00 AM – 5:00 PM, 4th Floor Exhibit Hall Hours: 9:00 AM – 6:00 PM, 3rd Floor Audio-Visual Practice Room: 7:00 AM – 6:00 PM, 4th Floor, office beside Registration Desk Cyber Cafe - Third Floor Atrium Lounge, 3 – Open Area Session 4 – Friday – 8:00-9:45 am Committee on Libraries and Information Resources Subcommittee on Copyright Issues - (Meeting) - Rhode Island, 5 4-01 War and Society Revisited: The Second World War in the USSR as Performance - Arlington, 3 Chair: Vojin Majstorovic, Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies (Austria) Papers: Roxane Samson-Paquet, U of Toronto (Canada) "Peasant Responses to War, Evacuation, and Occupation: Food and the Context of Violence in the USSR, June 1941–March 1942" Konstantin Fuks, U of Toronto (Canada) "Beyond the Soviet War Experience?: Mints Commission Interviews on Nazi-Occupied Latvia" Paula Chan, Georgetown U "Red Stars and Yellow Stars: Soviet Investigations of Nazi Crimes in the Baltic Republics" Disc.: Kenneth Slepyan, Transylvania U 4-02 Little-Known Russian and East European Research Resources in the San Francisco Bay Area - Berkeley, 3 Chair: Richard Gardner Robbins, U of New Mexico Papers: Natalia Ermakova, Western American Diocese ROCOR "The Russian Orthodox Church and Russian Emigration as Documented in the Archives of the Western American Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia" Galina Epifanova, Museum of Russian Culture, San Francisco "'In Memory of the Tsar': A Review of Memoirs of Witnesses and Contemporaries of Emperor Nicholas II from the Museum of Russian Culture of San Francisco" Liladhar R. -

Byronecho2136.Pdf

THE BYRON SHIRE ECHO Advertising & news enquiries: Mullumbimby 02 6684 1777 Byron Bay 02 6685 5222 seven Fax 02 6684 1719 [email protected] [email protected] http://www.echo.net.au VOLUME 21 #36 TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2007 echo entertainment 22,300 copies every week Page 21 $1 at newsagents only YEAR OF THE FLYING PIG Fishheads team wants more time at Brothel approval Byron Bay swimming pool goes to court Michael McDonald seeking a declaration the always intended ‘to hold Rick and Gayle Hultgren, development consent was activities involving children’ owners of the Byron Enter- null and void. rather than as for car parking tainment Centre, are taking Mrs Hultgren said during as mentioned in the staff a class 4 action in the Land public access at Council’s report. and Environment Court meeting last Thursday that ‘Over 1,000 people have against Byron Shire Coun- councillors had not been expressed their serious con- cil’s approval of a brothel aware of all the issues cern in writing. Our back near their property in the involved when considering door is 64 metres away from Byron Arts & Industry the brothel development the brothel in a direct line of Estate. An initial court hear- application (DA). She said sight. Perhaps 200 metres ing was scheduled for last their vacant lot across the would be better [as a Council Friday, with the Hultgrens street from the brothel was continued on page 2 Fishheads proprietors Mark Sims and Ralph Mamone at the pool. Photo Jeff Dawson Paragliders off to world titles Michael McDonald dispute came to prominence requirement for capital The lessees of the Byron Bay again with Cr Bob Tardif works. -

The Formation of Kyrgyz Foreign Policy 1991-2004

THE FORMATION OF KYRGYZ FOREIGN POLICY 1991-2004 A Thesis Presented to the Faculty Of The FletCher SChool of Law and DiplomaCy, Tufts University By THOMAS J. C. WOOD In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2005 Professor Andrew Hess (Chair) Professor John Curtis Perry Professor Sung-Yoon Lee ii Thomas J.C. Wood [email protected] Education 2005: Ph.D. Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University Dissertation Formation of Kyrgyz Foreign Policy 1992-2004 Supervisor, Professor Andrew Hess. 1993: M.A.L.D. Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University 1989: B.A. in History and Politics, University of Exeter, England. Experience 08/2014-present: Associate Professor, Political Science, University of South Carolina Aiken, Aiken, SC. 09/2008-07/2014: Assistant Professor, Political Science, University of South Carolina Aiken, Aiken, SC. 09/2006-05/2008: Visiting Assistant Professor, Political Science, Trinity College, Hartford, CT. 02/2005 – 04/2006: Program Officer, Kyrgyzstan, International Foundation for Election Systems (IFES) Washington DC 11/2000 – 06/2004: Director of Faculty Recruitment and University Relations, Civic Education Project, Washington DC. 01/1998-11/2000: Chair of Department, Program in International Relations, American University – Central Asia, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. 08/1997-11/2000: Civic Education Project Visiting Faculty Fellow, American University- Central Asia, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. Languages Languages: Turkish (advanced), Kyrgyz (intermediate), Russian (basic), French (intermediate). iii ABSTRACT The Evolution of Kyrgyz Foreign PoliCy This empirical study, based on extensive field research, interviews with key actors, and use of Kyrgyz and Russian sources, examines the formation of a distinct foreign policy in a small Central Asian state, Kyrgyzstan, following her independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. -

National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to 'Nation' Practice

National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to 'Nation' Practice Tatsiana Kulakevich SAIS Review of International Affairs, Volume 40, Number 2, Summer-Fall 2020, pp. 97-110 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/783885 [ Access provided at 7 Mar 2021 23:30 GMT from University Of South Florida Libraries ] National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to ‘Nation’ Practice Tatsiana Kulakevich This article examines the formation of nationalism in Belarus through two dimensions: elite ideology and everyday practice. I argue the presidential election of 2020 turned into a fundamental institutional crisis when a homogeneous set of ‘nation’ practices against the state ideology replaced existing elite ideology. This resulted in popular incremental changes in conceptions of national understanding. After twenty-six consecutive years in power, President Lukashenka unintentionally unleashed a process of national awakening leading to the rise of a new sovereign nation that demands the right to determine its own future, independent of geopolitical pressures and interference. Introduction ugust 2020 witnessed a resurgence of nationalist discourse in Belarus. AUnlike in the Transatlantic world, where politicians articulate visions of their nations under siege—by immigrants, refugees, domestic minority popu- lations—narratives of national and political failure dominate in Belarus Unlike trends in the Transatlantic resonate with large segments of the voting public.