Film Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

Quentin Tarantino's KILL BILL: VOL

Presents QUENTIN TARANTINO’S DEATH PROOF Only at the Grindhouse Final Production Notes as of 5/15/07 International Press Contacts: PREMIER PR (CANNES FILM FESTIVAL) THE WEINSTEIN COMPANY Matthew Sanders / Emma Robinson Jill DiRaffaele Villa Ste Hélène 5700 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 600 45, Bd d’Alsace Los Angeles, CA 90036 06400 Cannes Tel: 323 207 3092 Tel: +33 493 99 03 02 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] From the longtime collaborators (FROM DUSK TILL DAWN, FOUR ROOMS, SIN CITY), two of the most renowned filmmakers this summer present two original, complete grindhouse films packed to the gills with guns and guts. Quentin Tarantino’s DEATH PROOF is a white knuckle ride behind the wheel of a psycho serial killer’s roving, revving, racing death machine. Robert Rodriguez’s PLANET TERROR is a heart-pounding trip to a town ravaged by a mysterious plague. Inspired by the unique distribution of independent horror classics of the sixties and seventies, these are two shockingly bold features replete with missing reels and plenty of exploitative mayhem. The impetus for grindhouse films began in the US during a time before the multiplex and state-of- the-art home theaters ruled the movie-going experience. The origins of the term “Grindhouse” are fuzzy: some cite the types of films shown (as in “Bump-and-Grind”) in run down former movie palaces; others point to a method of presentation -- movies were “grinded out” in ancient projectors one after another. Frequently, the movies were grouped by exploitation subgenre. Splatter, slasher, sexploitation, blaxploitation, cannibal and mondo movies would be grouped together and shown with graphic trailers. -

Why Call Them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960S Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK

Why Call them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960s Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK Preface In response to the recent increased prominence of studies of "cult movies" in academic circles, this essay aims to question the critical usefulness of that term, indeed the very notion of "cult" as a way of talking about cultural practice in general. My intention is to inject a note of caution into that current discourse in Film Studies which valorizes and celebrates "cult movies" in particular, and "cult" in general, by arguing that "cult" is a negative symptom of, rather than a positive response to, the social, cultural, and cinematic conditions in which we live today. The essay consists of two parts: firstly, a general critique of recent "cult movies" criticism; and, secondly, a specific critique of the term "cult movies" as it is sometimes applied to 1960s American independent biker movies -- particularly films by Roger Corman such as The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967), by Richard Rush such as Hell's Angels on Wheels (1967), The Savage Seven, and Psych-Out (both 1968), and, most famously, Easy Rider (1969) directed by Dennis Hopper. Of course, no-one would want to suggest that it is not acceptable to be a "fan" of movies which have attracted the label "cult". But this essay begins from a position which assumes that the business of Film Studies should be to view films of all types as profoundly and positively "political", in the sense in which Fredric Jameson uses that adjective in his argument that all culture and every cultural object is most fruitfully and meaningfully understood as an articulation of the "political unconscious" of the social and historical context in which it originates, an understanding achieved through "the unmasking of cultural artifacts as socially symbolic acts" (Jameson, 1989: 20). -

THE BABADOOK Presskit D

EIN FILM VON JENNIFER KENT 93 Minuten // Australien/Kanada 2014 mit Essie Davis, Noah Wiseman, Daniel Henshall - Presseheft - Pressebilder: www.praesens.com www.facebook.com/DerBabadook 2 MISTER BABADOOK If it’s in a word or it’s in a look / You can’t get rid of The Babadook A rumbling sound, then 3 sharp knocks / ba BA-ba DOOK! DOOK! DOOK! / That’s when you’ll know that he’s around. / You’ll see him if you look. This is what he wears on top / He’s funny, don’t you think? / See him in your room at night / And you won’t sleep a wink. / I’ll soon take off my funny disguise / (take heed of what you’ve read...). / And once you see what’s underneath... / You’re going to wish you were... / DEAD. INHALT Kurzinhalt ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 4 Pressenotiz ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Langinhalt . 5 Cast & Crew . 7 Jennifer Kent (Regie, Drehbuch) / Interview ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 Essie Davis (Amelia) / Interview . 12 Noah Wiseman (Samuel) ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 Daniel Henshall (Robbie) ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 Hayley McElhinney (Claire) ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

The Nightingale

SCREEN AUSTRALIA SCREEN TASMANIA AND SOUTH AUSTRALIAN FILM CORPORATION present in association with ADELAIDE FILM FESTIVAL BRON CREATIVE And FILMNATION ENTERTAINMENT a CAUSEWAY FILMS and MADE UP STORIES production THE NIGHTINGALE PRODUCTION NOTES Running Time: 136 mins AUSTRALIAN PUBLICITY REQUESTS: Amy Burgess / National Publicity Manager, Transmission Films 02 8333 9000, [email protected] Images: High res images and poster available to download via the DOWNLOAD MEDIA tab at: https://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/the-nightingale Starring Aisling Franciosi, Sam Claflin and Baykali Ganambarr Writer and Director: Jennifer Kent Producers: Kristina Ceyton p.g.a., Bruna Papandrea p.g.a., Steve Hutensky p.g.a. and Jennifer Kent p.g.a. Executive Producers: Brenda Gilbert, Jason Cloth, Andrew Pollack, Aaron L. Gilbert, Ben Browning and Alison Cohen Associate Producer: Jim Everett Director of Photography: Radek Ladczuk Editor: Simon Njoo Production Designer: Alex Holmes Costume Designer: Margot Wilson APDG Hair and Makeup Designer: Nikki Gooley Sound Designer: Robert Mackenzie Composer: Jed Kurzel Visual Effects Supervisor: Marty Pepper Casting Director: Nikki Barrett CSA Distributed in Australia and New Zealand by Transmission Films International Sales: FilmNation Entertainment, US Sales: Endeavor Content The Nightingale Production Notes 2 INDEX SYNOPSES 3 DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT 4 CAST AND CHARACTER LIST 4 GENESIS OF THE FILM 5 CASTING AND CHARACTERS Clare – Portrayed by Aisling Franciosi 8 Hawkins – Portrayed by Sam Claflin 10 Billy -

The Short Stories of Playboy and the Crisis of Masculinity

The Short Stories of Playboy and the Crisis of Masculinity Men in Playboy’s Short Fiction and 1950s America Pieter-Willem Verschuren [3214117] [Supervisor: prof. dr. J. van Eijnatten] 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 State of the Art .................................................................................................................................... 4 History: Male Anxieties in the 1950s ............................................................................................... 5 Male Identity ................................................................................................................................... 7 Magazines ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Playboy ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Theoretical Framework ....................................................................................................................... 9 Gender ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Masculinity .................................................................................................................................... 12 Identity ......................................................................................................................................... -

Bamcinématek Presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 Days of 40 Genre-Busting Films, Aug 5—24

BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 days of 40 genre-busting films, Aug 5—24 “One of the undisputed masters of modern genre cinema.” —Tom Huddleston, Time Out London Dante to appear in person at select screenings Aug 5—Aug 7 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Jul 18, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, August 5, through Wednesday, August 24, BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, a sprawling collection of Dante’s essential film and television work along with offbeat favorites hand-picked by the director. Additionally, Dante will appear in person at the August 5 screening of Gremlins (1984), August 6 screening of Matinee (1990), and the August 7 free screening of rarely seen The Movie Orgy (1968). Original and unapologetically entertaining, the films of Joe Dante both celebrate and skewer American culture. Dante got his start working for Roger Corman, and an appreciation for unpretentious, low-budget ingenuity runs throughout his films. The series kicks off with the essential box-office sensation Gremlins (1984—Aug 5, 8 & 20), with Zach Galligan and Phoebe Cates. Billy (Galligan) finds out the hard way what happens when you feed a Mogwai after midnight and mini terrors take over his all-American town. Continuing the necessary viewing is the “uninhibited and uproarious monster bash,” (Michael Sragow, New Yorker) Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990—Aug 6 & 20). Dante’s sequel to his commercial hit plays like a spoof of the original, with occasional bursts of horror and celebrity cameos. In The Howling (1981), a news anchor finds herself the target of a shape-shifting serial killer in Dante’s take on the werewolf genre. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

Boskone 31 a Convention Report by Evelyn C

Boskone 31 A convention report by Evelyn C. Leeper Copyright 1994 by Evelyn C. Leeper Table of Contents: l Hotel l Dealers Room l Art Show l Programming l The First Night l Comic Books and Alternate History l Sources of Fear in Horror l Saturday Morning l Immoral Fiction? l Neglected SF and Fantasy Films l Turbulence and Psychohistory l Creating an Internally Consistent Religion l Autographing l Parties l Origami l The Forgotten Fantasists: Swann, Warner, and others l The City and The Story l What's BIG in the Small Press l The Transcendent Man--A Theme in SF and Fantasy l Does It Have to Be a SpaceMAN?: Gender and Characterization l Deconstructing Tokyo: Godzilla as Metaphor, etc. l The Green Room l Leaving l Miscellaneous l Appendix: Neglected Fantasy and Science Fiction Films Last year the drive was one hour longer due to the move from Springfield to Framingham, and three hours longer coming back, because there was a snowstorm added on as well. This year it was another hour longer going up because of wretched traffic, but only a half-hour longer coming back. (Going up we averaged 45 miles per hour, but never actually went 45 miles per hour--it was either 10 miles per hour or 70 miles per hour, and when it was 10, the heater was going full blast because the engine was over-heating.) Having everything in one hotel is nice, but is it worth it? Three years ago, panelists registered in the regular registration area and were given their panelist information there. -

This Month's Issue

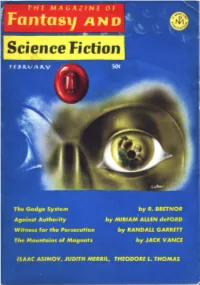

FEBRUARY Including Venture Science Fiction NOVELETS Against Authority MIRIAM ALLEN deFORD 20 Witness for the Persecution RANDALL GARRETT 55 The Mountains of Magnatz JACK VANCE 102 SHORT STORIES The Gadge System R. BRETNOR 5 An Afternoon In May RICHARD WINKLER 48 The New Men JOANNA RUSS 75 The Way Back D. K. FINDLAY 83 Girls Will Be Girls DORIS PITKIN BUCK 124 FEATURES Cartoon GAHAN WILSON 19 Books JUDITH MERRIL 41 Desynchronosis THEODORE L. THOMAS 73 Science: Up and Down the Earth ISAAC ASIMOV 91 Editorial 4 F&SF Marketplace 129 Cover by George Salter (illustrating "The Gadge System") Joseph W. Ferman, PUBLISHER Ed~mrd L. Fcrma11, EDITOR Ted White, ASSISTANT EDITOR Isaac Asimov, SCIENCE EDITOR Judith Merril, BOOK EDITOR Robert P. llfil/s, CONSULTING EDITOR The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Volnme 30, No. 2, Wlrolc No. 177, Feb. 1966. Plfblished monthly by Mercury Press, Inc., at 50¢ a copy. Aunual subscription $5.00; $5.50 in Canada and the Pan American Union, $6.00 in all other cormtries. Publication office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N.H. 03302. Editorial and ge11eral mail sholfld be sent to 3/7 East 53rd St., New York, N. Y. 10022. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N.H. Printed in U.S.A. © 1965 by Mercury Press, Inc. All riglrts inc/fl.ding translations iuto ot/rer la~>guages, resen•cd. Submissions must be accompanied by stamped, self-addressed ent•ciBPes; tire Publisher assumes no responsibility for retlfm of uusolicitcd ma1111scripts. BDITOBIAL The largest volume of mail which crosses our desk each day is that which is classified in the trade as "the slush pile." This blunt term is usually used in preference to the one y11u'll find at the very bottom of our contents page, where it says, ". -

Bamcinématek Presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, Oct 26—Nov 1 Highlighting 10 Tales of Rampaging Beasts and Supernatural Terror

BAMcinématek presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, Oct 26—Nov 1 Highlighting 10 tales of rampaging beasts and supernatural terror September 21, 2018/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, October 26 through Thursday, November 1 BAMcinématek presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, a series of 10 films showcasing two strands of Japanese horror films that developed after World War II: kaiju monster movies and beautifully stylized ghost stories from Japanese folklore. The series includes three classic kaiju films by director Ishirô Honda, beginning with the granddaddy of all nuclear warfare anxiety films, the original Godzilla (1954—Oct 26). The kaiju creature features continue with Mothra (1961—Oct 27), a psychedelic tale of a gigantic prehistoric and long dormant moth larvae that is inadvertently awakened by island explorers seeking to exploit the irradiated island’s resources and native population. Destroy All Monsters (1968—Nov 1) is the all-star edition of kaiju films, bringing together Godzilla, Rodan, Mothra, and King Ghidorah, as the giants stomp across the globe ending with an epic battle at Mt. Fuji. Also featured in Ghosts and Monsters is Hajime Satô’s Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell (1968—Oct 27), an apocalyptic blend of sci-fi grotesquerie and Vietnam-era social commentary in which one disaster after another befalls the film’s characters. First, they survive a plane crash only to then be attacked by blob-like alien creatures that leave the survivors thirsty for blood. In Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku (1960—Oct 28) a man is sent to the bowels of hell after fleeing the scene of a hit-and-run that kills a yakuza. -

Magazine Media

FEBRUARY 2010: THE FANTASY ISSUE M M MediaMagazine edia agazine Menglish and media centre issue 31 | februaryM 2010 Superheroes Dexter Vampires english and media centre Aliens Dystopia Apocalypses | issue 31 | february 2010 MM MM MediaMagazine is published by the English and Media Centre, a non-profit making organisation. editorial The Centre publishes a wide range of classroom materials and runs courses for teachers. If you’re studying English at A Level, look out e thought our last issue, on Reality, was one of our best yet, for emagazine, also published by Wbut this Fantasy-themed edition is just as inspired. Perhaps the Centre. our curiosity about the real and our fascination with fantasy are two sides of the same coin … The English and Media Centre 18 Compton Terrace By way of context, Annette Hill explores the factors behind London N1 2UN our current passion for the afterlife and the paranormal, while Telephone: 020 7359 8080 Chris Bruce suggests ways of investigating fantasy across media Fax: 020 7354 0133 platforms from an examiner’s perspective and Jerome Monahan provides an Email for subscription enquiries: illustrated history of fantasy at the movies via Jung, the Gothic and the ghost story. [email protected] We have a volley of vampires from Buffy to True Blood’s Bill, by way of Let The Right One In, and some persuasive and chilling accounts of how they represent real world Managing Editor: Michael Simons prejudices and fears. In a cluster of superhero articles, Matt Freeman explores the Editor: Jenny Grahame cultural significance of Superman, while Steph Hendry unpicks the ideologies of Editorial assistant/admin: superheroes and their relevance in a post-9/11 world – and identifies the world’s Rebecca Scambler first superheroic serial-killer.