The United States Army Corps of Engineers' Role in Natural Resources and Recreational Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adequacy and Predictive Value of Fish and Wildlife Planning Recommendations at Corps of Engineers __ '-/Pinal Reservoir Proiects 6

. Evaluation of Planning for Fish & Wildlife FINAL REPORT Adequacy and Predictive Value of Recommendation’s at Corps Projects December 1983 Approved for Department of the Army Public Release: Office of the Chief of Engineers Distribution Unlimited Washington. D C 20314 ltBRMtt JUN o4. l984 BUREAU OF RECLAMATION DENVER LIBRARY 92013381 ^2013301 UNCLASSIFIED SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE (When Data Entered) READ INSTRUCTIONS REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE BEFORE COMPLETING FORM 1. R E P O R T NUM BER 2. GOVT ACCESSION NO. 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NUMBER 4. T IT L E (and Subtitle) 5. TYPE OF REPORT ft PERIOD COVERED Adequacy and Predictive Value of Fish and Wildlife Planning Recommendations at Corps of Engineers __ '-/pinal Reservoir Proiects 6. PERFORMING ORGT REPORT NUMBER 7. A U T H O R S 8. CONTRACT OR GRANT NUMBERS Robert G. Martin, Norville S. Prosser and Gilbert C. Radonski DACW7 3-7 3-C-0040 DACW31-79-C-0005 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. PROGRAM ELEMENT, PROJECT, TASK Sport Fishing Institute 4-— AREA ft WORK UNIT NUMBERS 108 13th Street, N.W. * Washington, D.C. 20005 !1. CONTROLLING OFFICE NAME AND ADDRESS 12. R E P O R T D A T E Office, Chief of Engineers f December 1983 *j~ Washington, D.C. 20314 13. NUM BER O F PAG ES ' 1 97________________________ 14. M O N IT O R IN G A G EN CY NAM E ft ADDRESS^// different from Controlling Office) 15. S E C U R IT Y CLASS, (of this report) Unclassified 15*. DECL ASSI FI CATION/DOWNGRADING SCHEDULE 16. -

Assessment of Ohio River Water Quality Conditions

Assessment of Ohio River Water Quality Conditions 2010 - 2014 Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission 5735 Kellogg Avenue Cincinnati, Ohio 45230 www.orsanco.org June 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……. 1 Part I: Introduction……………………………………………………….……………………………………………….……………. 5 Part II: Background…………………………………………………………….…………………………………………….…….……. 7 Chapter 1: Ohio River Watershed………………………………..……………………………………….…………. 7 Chapter 2: General Water Quality Conditions………………………………….………………………….….. 14 Part III: Surface Water Monitoring and Assessment………………………………………………………………………. 23 Chapter 1: Monitoring Programs to Assess Ohio River Designated Use Attainment………… 23 Chapter 2: Aquatic Life Use Support Assessment…………………………………………………………….. 36 Chapter 3: Public Water Supply Use Support Assessment……………………………………………….. 44 Chapter 4: Contact Recreation Use Support Assessment…………………………………………………. 48 Chapter 5: Fish Consumption Use Support Assessment…………………………………………………… 57 Chapter 6: Ohio River Water Quality Trends Analysis………………………………………………………. 62 Chapter 7: Special Studies……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 64 Chapter 8: Integrated List……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 68 Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………. 71 FIGURES Figure 1. Ohio River Basin………………………………………………………………………………………….…………........ 6 Figure 2. Ohio River Basin with locks and dams.………………………………………………………………………..... 7 Figure 3. Land uses in the Ohio River Basin………………………………………………………………………………..… 8 Figure 4. Ohio River flow -

Army Civil Works Program Fy 2020 Work Plan - Operation and Maintenance

ARMY CIVIL WORKS PROGRAM FY 2020 WORK PLAN - OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE STATEMENT OF STATEMENT OF ADDITIONAL LINE ITEM OF BUSINESS MANAGERS AND WORK STATE DIVISION PROJECT OR PROGRAM FY 2020 PBUD MANAGERS WORK PLAN ADDITIONAL FY2020 BUDGETED AMOUNT JUSTIFICATION FY 2020 ADDITIONAL FUNDING JUSTIFICATION PROGRAM PLAN TOTAL AMOUNT AMOUNT 1/ AMOUNT FUNDING 2/ 2/ Funds will be used for specific work activities including AK POD NHD ANCHORAGE HARBOR, AK $10,485,000 $9,685,000 $9,685,000 dredging. AK POD NHD AURORA HARBOR, AK $75,000 $0 Funds will be used for baling deck for debris removal; dam Funds will be used for commonly performed O&M work. outlet channel rock repairs; operations for recreation visitor ENS, FDRR, Funds will also be used for specific work activities including AK POD CHENA RIVER LAKES, AK $7,236,000 $7,236,000 $1,905,000 $9,141,000 6 assistance and public safety; south seepage collector channel; REC relocation of the debris baling area/construction of a baling asphalt roads repairs; and, improve seepage monitoring for deck ($1,800,000). Dam Safety Interim Risk Reduction measures. Funds will be used for specific work activities including AK POD NHS DILLINGHAM HARBOR, AK $875,000 $875,000 $875,000 dredging. Funds will be used for dredging environmental coordination AK POD NHS ELFIN COVE, AK $0 $0 $75,000 $75,000 5 and plans and specifications. Funds will be used for specific work activities including AK POD NHD HOMER HARBOR, AK $615,000 $615,000 $615,000 dredging. Funds are being used to inspect Federally constructed and locally maintained flood risk management projects with an emphasis on approximately 11,750 of Federally authorized AK POD FDRR INSPECTION OF COMPLETED WORKS, AK 3/ $200,000 $200,000 and locally maintained levee systems. -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

Birding Sites in Johnson County Babcock Access GPS Coordinates: 41.7839530715082,-91.7002201080322

IOWA ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION - Birding Sites in Johnson County Printed on 9/30/2021 Babcock Access GPS Coordinates: 41.7839530715082,-91.7002201080322 Has Site Guide Ownership: State Description: Boat ramp into Hawkeye WMA, but the fields on the way in and the trees can be good. Access and birding very much effected by water levels of the Coraville Reservoir Habitat: Beyond a small wooded area at the turn off from Swan Lake Rd. The habitat is row crop, sheetwater or mudflat depending on the water levels in the reservoir. Either of those can be good for shorebirds or waterfowl. The old oxbow, Babcock Lake, is a narrow channel that sometimes contains interesting birds. The old parking lot at end of the old road has a good view of the flats, E towards Sand Point. Directions: On the upper Coralville Reservoir, Hawkeye W.A., northwest Johnson Co. A few miles north of I-80, take the North Liberty/F-28 exit off I-380. Go west on F-28 about 3.5 miles to Greencastle Ave. Take Greencastle 1.5 miles north to Swan Lake Rd., just after a pond on your right. Turn right (east) on Swan Lake, a B-level road here, 0.8 mile to the Babcock entrance road on your left. Follow this to its end at a small parking area. Where the road turns left to the parking lot and boat ramp, an old road goes NE from this left turn and may be walked sometimes. This can also be accessed from Swan Lake, going W. The road is often in better shape coming from the E. -

New England District Team Commemorates Surry Mountain Lake Dam's 75Th Anniversary by Ann Marie R

New England District team commemorates Surry Mountain Lake Dam's 75th anniversary By Ann Marie R. Harvie, USACE New England District For the last 75 years, Surry Mountain Lake Dam in Surry, New Hampshire has stood at the ready to protect New Hampshire residents from flooding. The District team members who operate the project held a 75th anniversary event on October 1 from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., to commemorate the opening of the dam. “Among the participants that came to the event was a gentleman that worked at Surry Dam in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s,” said Park Ranger Eric Chouinard. “He shared some of his stories and experiences with us.” During the event, Chouinard and Park Ranger Alicia Lacrosse each gave a presentation. “The first was a history presentation,” said Chouinard. “I discussed life in the small town of Surry before the dam’s construction, a brief overview of the history of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the highly important Flood Control Act of 1936 which paved the way for the construction of Surry Dam, the reasoning behind why the town of Surry was chosen as the location for a flood control dam as opposed to other locations in Cheshire County, a brief history with pictures of the flood of 1936 and the hurricane of 1938, which both contributed to the construction of the Surry Dam.” Chouinard’s presentation also featured many historical construction photos. A presentation on invasive plants was given by Lacrosse. “The invasive presentation identified many of the species of local interest, such as Glossy Buckthorn, Japanese Knotweed, Autumn Olive and Eurasian Milfoil,” said Chouinard. -

The Case of the Shrinking Law Schools

MUSIC BUSINESS Preschool kings of cool Former Franklin teachers takes The Zinghoppers to Barney-like heights REAL ESTATE TRENDS Insider P16 trading Nashville Waiting for the perfect house to be listed? Someone with DaviLedgerDson • Williamson • sUmnER • ChEatham • Wilson RUthERFoRD • R better intel just bought it. P7 oBERtson • maURY • DiCkson • montGomERY | The power of www.nashvilleledger.cominformation.July 19 – 25, 2013 The case of the Vol. 39 | Issue 29 F oR mer lY shrinking WESTVIEW sinCE 1978 Page 13 law schools Enrollment slides as potential Dec.: students argue costs v. benefits Dec.: Keith Turner, Ratliff, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Resp.: Kimberly Dawn Wallace, Atty: By Mary C Lagrone, 08/24/2010, 10P1318 Jeannie Naujeck In re: Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates,Dec.: Resp.: Kim Prince Patrick, Angelo Terry Patrick, Gates, Atty: Monica D Edwards, 08/25/2010, 10P1326 In re: Keith Turner, TN Dept Of Correction, www.westviewonline.com TN Dept Of Correction, Resp.: Johnny Moore,Dec.: Melinda Atty: Bryce L Tomlinson, Coatney, Resp.: Pltf(s): Rodney A Hall, Pltf Atty(s): n/a, 08/27/2010, 10P1336 In re: Kim Patrick, Terry Patrick, | Correspondent Pltf(s): Sandra Heavilon, Resp.: Jewell Tinnon, Atty: Ronald Andre Stewart, 08/24/2010,Dec.: Seton Corp 10P1322 Insurance Company, Dec.: Regions Bank, Resp.: Leigh A Collins, In re: Melinda L Tomlinson, Def(s): Jit Steel Transport Inc, National Fire Insurance Company, Elizabeth D Hale, Atty: William Warner McNeilly, 08/24/2010, ith lawyer jokes, -

Birding Sites in Johnson County Babcock Access GPS Coordinates

IOWA ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION - Birding Sites in Johnson County Printed on 4/27/2019 Babcock Access GPS Coordinates: 41.7839530715082,-91.7002201080322 Has Site Guide Ownership: State Description: Boat ramp into Hawkeye WMA, but the fields on the way in and the trees can be good. Access and birding very much effected by water levels of the Coraville Reservoir Habitat: Beyond a small wooded area at the turn off from Swan Lake Rd. The habitat is row crop, sheetwater or mudflat depending on the water levels in the reservoir. Either of those can be good for shorebirds or waterfowl. The old oxbow, Babcock Lake, is a narrow channel that sometimes contains interesting birds. The old parking lot at end of the old road has a good view of the flats, E towards Sand Point. Directions: On the upper Coralville Reservoir, Hawkeye W.A., northwest Johnson Co. A few miles north of I-80, take the North Liberty/F-28 exit off I-380. Go west on F-28 about 3.5 miles to Greencastle Ave. Take Greencastle 1.5 miles north to Swan Lake Rd., just after a pond on your right. Turn right (east) on Swan Lake, a B-level road here, 0.8 mile to the Babcock entrance road on your left. Follow this to its end at a small parking area. Where the road turns left to the parking lot and boat ramp, an old road goes NE from this left turn and may be walked sometimes. This can also be accessed from Swan Lake, going W. The road is often in better shape coming from the E. -

Peddling a Greener Path

GREEN BUSINESS Peddling a greener path Rush Messengers is helping Native magazine offset its carbon footprint. MUSIC INDUSTR Planting P2 Nashville Roots on PY BS ‘Music City Roots’ takes the Loveless Barn show to 71 DaviLedgerDson • Williamson • sUmnER • ChEatham • Wilson RUthERFoRD • R PBS stations nationwide. P17 oBERtson • maURY • DiCkson • montGomERY | September 13 – 19, 2013 www.nashvilleledger.com The power of information. Vol. 39 | Nashville publisher Issue 37 targets new audiences F oR mer lY with bold WESTVIEW sinCE 1978 acquisitions Page 13 Dec.: Dec.: Keith Turner, Ratliff, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Resp.: Kimberly Dawn Wallace, Atty: Mary C Lagrone, 08/24/2010, 10P1318 In re: Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates,Dec.: Resp.: Kim Prince Patrick, Angelo Terry Patrick, Gates, Atty: Monica D Edwards, 08/25/2010, 10P1326 In re: Keith Turner, TN Dept Of Correction, www.westviewonline.com TN Dept Of Correction, Resp.: Johnny Moore,Dec.: Melinda Atty: Bryce L Tomlinson, Coatney, Resp.: Pltf(s): Rodney A Hall, Pltf Atty(s): n/a, 08/27/2010, 10P1336 In re: Kim Patrick, Terry Patrick, Pltf(s): Sandra Heavilon, Resp.: Jewell Tinnon, Atty: Ronald Andre Stewart, 08/24/2010,Dec.: Seton Corp 10P1322 Insurance Company, Dec.: Regions Bank, Resp.: Leigh A Collins, In re: Melinda L Tomlinson, Def(s): Jit Steel Transport Inc, National Fire Insurance Company, Elizabeth D Hale, Atty: William Warner McNeilly, 08/24/2010, Def Atty(s): J Brent Moore, 08/26/2010, 10C3316 10P1321 Dec.: Amy Sandra Heavilon -

White Mountain National Forest TTY 603 466-2856 Cover: a Typical Northern Hardwood Stand in the Mill Brook Project Area

Mill Brook United States Department of Project Agriculture Forest Final Service Eastern Environmental Assessment Region Town of Stark Coos County, NH Prepared by the Androscoggin Ranger District November 2008 For Information Contact: Steve Bumps Androscoggin Ranger District 300 Glen Road Gorham, NH 03581 603 466-2713 Ext 227 White Mountain National Forest TTY 603 466-2856 Cover: A typical northern hardwood stand in the Mill Brook project area. This document is available in large print. Contact the Androscoggin Ranger District 603-466-2713 TTY 603-466-2856 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activi- ties on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Printed on Recycled Paper Mill Brook Project — Environmental Assessment Contents Chapter 1: Purpose and Need......................................................5 1.0 Introduction...............................................................5 1.1 Purpose of the Action and Need for Change . .7 1.2 Decision to be Made .......................................................11 1.3 Public Involvement........................................................12 1.4 Issues . .13 1.5 Alternatives Considered but Not Analyzed in Detail ...........................14 Chapter 2. -

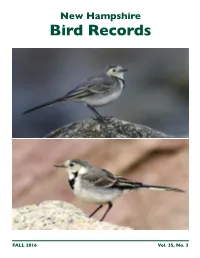

NH Bird Records

New Hampshire Bird Records FALL 2016 Vol. 35, No. 3 IN HONOR OF Rob Woodward his issue of New Hampshire TBird Records with its color cover is sponsored by friends of Rob Woodward in appreciation of NEW HAMPSHIRE BIRD RECORDS all he’s done for birds and birders VOLUME 35, NUMBER 3 FALL 2016 in New Hampshire. Rob Woodward leading a field trip at MANAGING EDITOR the Birch Street Community Gardens Rebecca Suomala in Concord (10-8-2016) and counting 603-224-9909 X309, migrating nighthawks at the Capital [email protected] Commons Garage (8-18-2016, with a rainbow behind him). TEXT EDITOR Dan Hubbard In This Issue SEASON EDITORS Rob Woodward Tries to Leave New Hampshire Behind ...........................................................1 Eric Masterson, Spring Chad Witko, Summer Photo Quiz ...............................................................................................................................1 Lauren Kras/Ben Griffith, Fall Fall Season: August 1 through November 30, 2016 by Ben Griffith and Lauren Kras ................2 Winter Jim Sparrell/Katie Towler, Concord Nighthawk Migration Study – 2016 Update by Rob Woodward ..............................25 LAYOUT Fall 2016 New Hampshire Raptor Migration Report by Iain MacLeod ...................................26 Kathy McBride Field Notes compiled by Kathryn Frieden and Rebecca Suomala PUBLICATION ASSISTANT Loon Freed From Fishing Line in Pittsburg by Tricia Lavallee ..........................................30 Kathryn Frieden Osprey vs. Bald Eagle by Fran Keenan .............................................................................31 -

Ohio River Basin Pilot Study

Institute for Water Resources–Responses to Climate Change Program Ohio River Basin Pilot Study CWTS report 2017-01, May 2017 OHIO RIVER BASIN– Formulating Climate Change Mitigation/Adaptation Strategies through Regional Collaboration with the ORB Alliance U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Ohio River Basin Alliance Institute for Water Resources, Responses to Climate Change Program Sunrise on the Ohio River. January, 2014. i Institute for Water Resources–Responses to Climate Change Program Ohio River Basin Pilot Study i Institute for Water Resources–Responses to Climate Change Program Ohio River Basin Pilot Study Ohio River Basin Climate Change Pilot Study Report ABSTRACT The Huntington District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, in collaboration with the Ohio River Basin Alliance, the Institute for Water Resources, the Great Lakes and Ohio River Division, and numerous other Federal agencies, non-governmental organizations, research institutions, and academic institutions, has prepared the Ohio River Basin Climate Change Pilot Report. Sponsored and supported by the Institute for Water Resources through its Responses to Climate Change program, this report encapsulates the research of numerous professionals in climatology, meteorology, biology, ecology, geology, hydrology, geographic information technology, engineering, water resources planning, economics, and landscape architecture. The report provides downscaled climate modeling information for the entire basin with forecasts of future precipitation and temperature changes as well as forecasts of future streamflow at numerous gaging points throughout the basin. These forecasts are presented at the Hydrologic Unit Code-4 sub-basin level through three 30-year time periods between 2011 and 2099. The report includes the results of preliminary investigations into the various impacts that forecasted climate changes may have on both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems and operating water resources infrastructure.