Otter Handout in One File 30

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navajo Reservoir and San Juan River Temperature Study 2006

NAVAJO RESERVOIR AND SAN JUAN RIVER TEMPERATURE STUDY NAVAJO RESERVOIR BUREAU OF RECLAMATION 125 SOUTH STATE STREET SALT LAKE CITY, UT 84138 Navajo Reservoir and San Juan River Temperature Study Page ii NAVAJO RESERVOIR AND SAN JUAN RIVER TEMPERATURE STUDY PREPARED FOR: SAN JUAN RIVER ENDANGERED FISH RECOVERY PROGRAM BY: Amy Cutler U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Upper Colorado Regional Office FINAL REPORT SEPTEMBER 1, 2006 ii Navajo Reservoir and San Juan River Temperature Study Page iii TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...............................................................................................1 1. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................3 2. OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................5 3. MODELING OVERVIEW .......................................................................................6 4. RESERVOIR TEMPERATURE MODELING ......................................................7 5. RIVER TEMPERATURE MODELING...............................................................14 6. UNSTEADY RIVER TEMPERATURE MODELING........................................18 7. ADDRESSING RESERVOIR SCENARIOS USING CE-QUAL-W2................23 7.1 Base Case Scenario............................................................................................23 7.2 TCD Scenarios...................................................................................................23 -

Mineral Resource Potential of the Piedra Wilderness Study Area, Archuleta and Hinsdale Counties, Colorado

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MISCELLANEOUS FIELD STUDIES UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP MF-1630-A PAMPHLET MINERAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL OF THE PIEDRA WILDERNESS STUDY AREA, ARCHULETA AND HINSDALE COUNTIES, COLORADO By Alfred L. Bush, Steven H. Condon, and Karen J. Franczyk, U.S. Geological ·Survey and s. Don Brown, U.S. Bureau of Mines STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS Under the provisions of the Wilderness Act (Public Law 88-577, September 3, 1964) and related acts, the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines have been conducting mineral surveys of wilderness and primitivE.. areas. Areas officially designated as "wilderness," "wild," or "canoe" when the act was passed were incorporated into the National Wilderness Preservation System, and some of them are being studied at present. The act provided that areas under consideration for wilderness designation should be studied for suitability for incorporation into the Wilderness System. The mineral surveys constitute one aspect of the suitability studies. The act directs that the results of such surveys are to be made available to the public and be submit ted to the President and the Congress. This report discusses the · results of a mineral survey of the Piedra Wilderness Study Area, San Juan National Forest, Archuleta and Hinsdale Counties, Colorado. The area was established as a wilderness study area by Public Law 96-560, known as the Colorado Wilderness Act of 1980. MINERAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL SUMMARY STATEMENT The mineral resource potential of the Piedra Wilderness Study Area is low. No occurrences of metallic minerals, of valuable industrial rocks and minerals, or of useful concentrations of organic fuels are known in the study area. -

Navajo State Park Hunting

.S. 160 LEGEND r To U e Camping v i R a r Fishing d ie P unctionHunting is permitted at Navajo State Park during lawful hunting seasons, during Boat Ramp lawful hunting hours, with a valid hunting Piedra River mile 1 license and only in the areas designated Marina Navajo State Park WATCHABLE WILDLIFE w Gauge J on this hunting map. VIEWING AREA Hunting Area Hunting Map ro *All vehicles must display a valid Nar Colorado State Parks pass. Day-Use Site .7 Primitive Camping/ Deer Run Day-Use Site 1 mile erlook Piedra Flats oint West Piedra uan Ov es .9 uan Flats San J Allison Arboles.8 P .8 ood Arboles San.6 J S-Curv 2.2 miles To Ignacio Windsurf Cottonw Beach To Pagosa Junction Sambrito Wetlands San Juan River COLORADO Archuleta County New Mexico Hunting at Navajo State Park is permitted ONLY as follows: Mileage from Highway 151 • Along the West side of the Reservoir, along the Piedra River: From 100 yards from the northern end of Windsurf Beach AREA MILEAGE on CR 500 Campground parking area, upriver to 100 yards south of the Watchable Wildlife Area, and 100 yards east toward the lake from Narrow Gauge Junction 1.0 mile the Piedra Trail, and 50 feet from the center of any roadway or from any parking lot. Deer Run 1.7 miles • Along the East side of the Reservoir, along the Piedra River: From the southwestern end of the parking lot at Narrow Gauge Piedra Flats 2.7 miles Junction Day Use Area to 100 yards north of Arboles Point Campground, and 100 yards west toward the lake from the Piedra Arboles Point 3.6 miles Trail, and 50 feet from the center of any roadway or from any parking lot. -

Piedra Valley Ranch Pagosa Springs, Colorado

PIEDRA VALLEY RANCH PAGOSA SPRINGS, COLORADO $33,900,000 | 9,600± ACRES LISTING AGENT: CODY LUJAN 3001 SOUTH LINCOLN AVE., SUITE E STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLORADO 80487 P: 970.879.5544 M: 303.819.8064 [email protected] PIEDRA VALLEY RANCH PAGOSA SPRINGS, COLORADO $33,900,000 | 9,600± ACRES LISTING AGENT: CODY LUJAN 3001 SOUTH LINCOLN AVE., SUITE E STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLORADO 80487 P: 970.879.5544 M: 303.819.8064 [email protected] Land… that’s where it all begins. Whether it is ranch land or family retreats, working cattle ranches, plantations, farms, estancias, timber or recreational ranches for sale, it all starts with the land. Since 1946, Hall and Hall has specialized in serving the owners and prospective owners of quality rural real estate by providing mortgage loans, appraisals, land management, auction and brokerage services within a unique, integrated partnership structure. Our business began by cultivating long-term relationships built upon personal service and expert counsel. We have continued to grow today by being client-focused and results-oriented—because while it all starts with the land, we know it ends with you. WITH OFFICES IN: DENVER, COLORADO BOZEMAN, MONTANA EATON, COLORADO MISSOULA, MONTANA STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLORADO VALENTINE, NEBRASKA STERLING, COLORADO COLLEGE STATION, TEXAS SUN VALLEY, IDAHO LAREDO, TEXAS HUTCHINSON, KANSAS LUBBOCK, TEXAS BUFFALO, WYOMING MELISSA, TEXAS BILLINGS, MONTANA SOUTHEASTERN US SALES | AUCTIONS | FINANCE | APPRAISALS | MANAGEMENT © 2020 HALL AND HALL | WWW.HALLANDHALL.COM | [email protected] — 2 — EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Blessed with tremendous views of the dramatic San Juan Mountain Range, Piedra Valley Ranch is distinguished by an unequalled combination of size, recreational amenities, wildlife, scenery, and immediate proximity to a mountain resort community. -

Navajo State Park Brochure

Passes and Permits COLORADO PARKS & WILDLIFE A Colorado State Parks Pass is required on all Navajo State Park motor vehicles entering the park. All passes Developed Area must be properly attached or displayed in the vehicle. An annual Pass is valid at any Colorado State Park for a year from the date of purchase. Navajo The Aspen Leaf annual pass is available to Colorado Seniors at a discounted rate. Daily State Park passes are available at the park entrance stations, self-service dispensers and ENJOY YOUR STATE PARKS ANS Inspection all State Park offices. Station Colorado Disabled Veterans displaying the Colorado Disabled Veteran (DV) license plates are admitted free without a pass, however, a camping fee is charged. All campers are required to purchase a valid camping permit. Emergencies In an emergency, contact a ranger or call the ANS Decon Archuleta Sheriff at 970-731-2160. Station Marina Dry Storage Reservations Call 1-800-244-5613 or view cpw.state.co.us to reserve campsites. Call 303-297-1192, for customer service, 8am-5pm M-F. AVAJO STATE PARK is a park that narrow gauge railway that once was the area’s offers recreation, history, wildlife and transportation lifeline. The Denver and Rio the beauty of southwest Colorado. It Grande railroad served the towns of Rosa and Nis situated just outside of the town of Arboles, the old town of Arboles, both of which now rest Navajo State Park 35 miles southwest of Pagosa Springs, and 45 under the reservoir’s surface. The Cumbres and miles southeast of Durango, Colorado. -

Piedra Forks River Ranch Pagosa Springs, Colorado

Our Luxury Colection Piedra Forks River Ranch Pagosa Springs, Colorado A TALE Prope OF TWO RIVERS. r There y is Overview a place, in southwestern Colorado, where stunning views, exquisite architecture and two rivers collide. This is Piedra Forks Ranch. Nestled on 169 acres in the Upper Piedra river valley near Pagosa Springs, Piedra Forks Ranch offers 1.5 miles of East Fork Piedra River frontage and 1 mile of the Middle Fork Piedra River. With varied terrain, the property boasts abundant wildlife and foliage, as well as a large pond, a Naonally acclaimed main home, a guest home and two addional cabins. Very rarely do majesc views, abundant water and magnificent improvements wind together as they do on this very special ranch. Welcome home. Presented By Galles Properes | LEADERS IN SW COLORADO REAL ESTATE | 970.264.1250 | www.GallesProperes.com | [email protected] | Riverfront Masterpiece Te Lifetyle Located in the coveted Upper Piedra River Valley, Piedra Forks Ranch is dissected by two Rivers, with 1.5 miles of the East Fork Piedra River and 1 mile of the Middle Fork Piedra River. Completely fenced, this 169 acre property offers diverse terrain, with winding river valley, lush pasture and stunning views of the San Juan Mountains and Weminuche range. Wildlife abounds, with blue ribbon fly fishing and unlimited year-round recreaonal acvies. Presented By Galles Properes | LEADERS IN SW COLORADO REAL ESTATE | 970.264.1250 | www.GallesProperes.com | [email protected] | Mountain Luxury Te Reidence The main home, designed by Yale School of Architecture Hall of Fame inductee Peter H. -

Navajo Hunting

LEGEND r To U.S. 160 e Camping v i R a r Fishing d ie P Boat Ramp NAVAJO STATE PARK Piedra River mile 1 Marina Hunting Map WATCHABLE WILDLIFE VIEWING AREA Hunting Area Hunting is permitted at Navajo State Park during lawful hunting seasons, during lawful hunting hours, Narrow Gauge Junction Day-Use Site with a valid hunting license and only in the areas .7 Primitive Camping/ designated on this hunting map. Deer Run * All vehicles must display a valid Day-Use Site Colorado State Parks pass. 1 mile Piedra Flats West Piedra .9 San Juan Overlook Allison Arboles Arboles.8 Point.8 San.6 Juan FlatsS-Curves 2.2 miles To Ignacio Windsurf Cottonwood Beach To Pagosa Junction Sambrito Wetlands San Juan River COLORADO Archuleta County New Mexico Hunting is permitted ONLY in the following areas: Mileage from Highway 151 • From Windsurf Beach and Arboles Point, beginning where the Piedra River enters Navajo Reservoir, to the northern parking AREA MILEAGE on CR 500 lot at the West Piedra Day-Use Area on the east side of the river, and the Deer Run Day-Use Area parking lot on the west side Narrow Gauge Junction 1.0 mile of the river. At the West Piedra Day-Use Area, a metal gate on the Piedra Trail designates the Parkʼs northern hunting area Deer Run 1.7 miles boundary. At the Deer Run Day-Use Area, the northern edge of the parking lot designates the Parkʼs northern hunting Piedra Flats 2.7 miles area boundary. Arboles Point 3.6 miles • From Arboles Point, beginning where the San Juan River enters Navajo Reservoir, southwest to the Cottonwood Day-Use Area. -

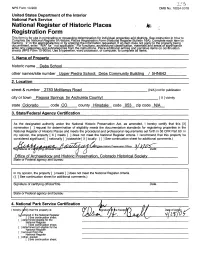

National Register of Historic Places Fo Registration Form This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determination for Individual Properti.Es Arid Districts

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places fo Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properti.es arid districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter * N/A for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance enter only categories and subcategones frpm the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on confirmation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________ historic name Debs School______________________________________ other names/site number Upper Piedra School: Debs Community Building / 5HN642______ 2. Location_________________________________________________ street & number 2783 McManus Road____________________ [N/A] not for publication city or town Pagosa Springs Fin Archuleta Countvl_________________ [ x ] vicinity state Colorado___ code CO county Hinsdale code 053 zip code N/A 3. State/Federal Agency Certification __ _______ As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [ X ] meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant [ ] nationally [ ] statewide [ X ] locally. -

Chapter 3 Affected Environment

Navajo Reservoir RMP/FEA * * * * June 2008 CHAPTER 3 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT RESERVOIR AREA The Navajo Reservoir Area consists of the area acquired or withdrawn by Reclamation for the Navajo Unit of the Colorado River Storage Project and retained for the construction, operation, and maintenance of the Unit and associated facilities to meet project purposes. The reservoir area includes the reservoir, a generally narrow strip of uplands surrounding the reservoir, about 5.5 miles of a relatively narrow strip along the San Juan River below the dam, and a detached 160- acre parcel about 2.5 miles northwest of the dam. The reservoir area straddles the Colorado/New Mexico state line. About 15 percent of the reservoir is within Colorado. The remaining 85 percent is within New Mexico. The Colorado portion of the reservoir area is all within the boundaries of the Southern Ute Indian Reservation. Land ownership adjacent to the reservoir area is mixed. In New Mexico, the adjoining land includes private, Federal (BLM), and State (NM) ownership. In Colorado the adjoining land includes private and Southern Ute Indian Tribe (SUIT) ownership. PARTNERSHIPS Reclamation currently has several partnerships in place at Navajo Reservoir. These include partnerships with Colorado Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation (CDPOR), New Mexico State Parks Division (NMSPD), New Mexico Game and Fish Department (NMGFD), and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Both CDPOR and NMSPD manage recreation and certain other resources at Navajo Reservoir in their respective states in accordance with agreements with Reclamation and applicable federal and state laws and regulations. CDPOR is currently managing Navajo State Park under a 1994 agreement, while NMSPD is managing Navajo Lake State Park under a twice amended 1972 agreement. -

Navajo State Park Motor Vehicles Entering the Park

Passes and Permits COLORADO PARKS & WILDLIFE A Colorado State Parks Pass is required on all Navajo State Park motor vehicles entering the park. All passes Developed Area are to be displayed on the lower right inside of the windshield. An annual Pass is valid at any Colorado State Park for a year from the date Navajo of purchase. The Aspen Leaf annual pass is available to Colorado Seniors at a discounted State Park rate. Daily passes are available at the park entrance stations, self-service dispensers and ENJOY YOUR STATE PARKS ANS Inspection all State Park offices. Station Colorado Disabled Veterans displaying the Colorado Disabled Veteran (DV) license plates are admitted free without a pass, however, a camping fee is charged. All campers are required to purchase a valid camping permit. Emergencies In an emergency, contact a ranger or call the ANS Decon Archuleta Sheriff at 970-731-2160. Station Marina Dry Storage Reservations Call 800-678-2267 or view cpw.state.co.us to reserve campsites. In Denver, call 303-470-1144. AVAJO STATE PARK is a park that narrow gauge railway that once was the area’s offers recreation, history, wildlife and transportation lifeline. The Denver and Rio the beauty of southwest Colorado. It Grande railroad served the towns of Rosa and Nis situated just outside of the town of Arboles, the old town of Arboles, both of which now rest Navajo State Park 35 miles southwest of Pagosa Springs, and 45 under the reservoir’s surface. The Cumbres and miles southeast of Durango, Colorado. The Toltec and the Durango and Silverton Railroads PO Box 1697 • 1526 County Road 982 park’s finest attraction is the 35-mile long Navajo are today the remaining working portions of Arboles, CO 81121 Reservoir that begins in Colorado and ends in this railway. -

The Geology of Pagosa Country

The Geology of Pagosa Country Written by Rick Stinchfield Windswept shores, leafy swamps, open oceans, and, yes, plenty of fire and ice, are all hallmarks of the geology of the Pagosa Ranger District of the San Juan National Forest. The rocks that are exposed here are of vastly different ages. The oldest, found only along the Piedra River Trail near Weminuche Creek and further downstream, are the slates and other metamorphic rocks of the Uncompahgre Formation, more than a billion and a half years old. The Uncompahgre is intruded by the slightly younger Eolus Granite, a handsome, often pink, intrusive igneous rock. It, too, outcrops in the very bottom of the Piedra River gorge, but is more easily seen around Granite Lake, just outside the district near the Weminuche Trail. The Eolus is radiometrically dated at 1.46 billion years old. In the geologic record it is common for vast periods of time to be missing in the rock sequence. These are called uncomformities, and reflect environments of erosion rather than deposition. Between the Eolus Granite and the overlying Hermosa Formation more than a billion years are absent in the stratigraphy. The Hermosa was laid down as shoreline deposits along the east edge of a basin that formed as the Ancestral Rockies were elevated some 300 million years ago (300 ma). A quite similar unit, the Cutler Formation, overlies the Hermosa, and also consists of shales derived from clay, and siltstones of very fine sand grains. These two Basalt "fins" north side of Wolf Creek Pass. strata may be observed along the First Fork Road (open seasonally) north of route 160. -

From the Bottom of the Ocean to the Top of the World (…And Everything in Between): the Geology of Pagosa Country

Geology of Pagosa Country, Colorado From The Bottom Of The Ocean To The Top Of The World (…and Everything in Between): The Geology of Pagosa Country Compiled by Glenn Raby Geologist (Retired) Pagosa Ranger District/Field Office San Juan National Forest & BLM Public Lands Pagosa Springs, Colorado October, 2009 Page 1 Geology of Pagosa Country, Colorado The Geology of Pagosa Country Contents Text & Tables Introduction Page 3 Pagosa Country Geologic History: the Text Page 4 Pagosa Country Geologic History: the Table Page 7 The Geologic Story of Chimney Rock Page 18 Treasure Mountain Geology and Lore Page 24 A Relic of Chixulub? A Geological Whodunit Page 26 Mosasaur! Page 31 Ophiomorpha Fossil Burrows Page 34 Geologic Road Logs Pagosa Country Geologic History Page 35 East Fork Fire, Ice and Landslide Page 43 A Shattered Landscape Page 59 South Fork to Creede Page 69 Ice Cave Ridge Page 74 Geologic Map Symbol Explanation Page 84 PowerPoint Presentations on this disk TIMELINE.ppt Geologic History of Pagosa Country SAN JUAN SUPERVOLCANO.ppt La Garita Caldera October, 2009 Page 2 Geology of Pagosa Country, Colorado Introduction Pagosa Country existed long before humans began carving up the land into political territories. It is roughly that area of Colorado south of the Continental Divide, west of the Navajo River, north of Chama, New Mexico, and east of the Piedra River and Chimney Rock. Of course, local experts may prefer other dividing lines, but Pagosa Country is broadly united by a complex and dramatic geologic past that built this land we live in and love. Pagosa Country has existed as long as the Earth, so in that respect its beginnings are no different that those of our home planet.