The Prospect from Rugman's Row: the Row House in Late Sixteenth- and Early Seventeenth-Century London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discover More Abingdon.Org.Uk Independent Education for Boys from 4-18 Years and Girls Aged 4-7

Abingdon School 01235 849041 Abingdon Prep School 01865 391570 discover more abingdon.org.uk Independent education for boys from 4-18 years and girls aged 4-7 www.artweeks.org 1 CÉZANNE AND THE MODERN Masterpieces of European Art from the Pearlman Collection BOOK NOW 13 March–22 June 2014 www.ashmolean.org Free for Members & Under 12s WELCOME Oxfordshire Artweeks 2014 Welcome to the 32nd Oxfordshire Artweeks festival during which you can see, for free, spectacular art at hundreds of places, in artists’ homes and studios, along village trails and city streets, in galleries and gardens. It is your chance, whether a seasoned art enthusiast or an interested newcomer to enjoy art in a relaxed way, to meet the makers and see their creative talent in action. Browse the listings and the accompanying website where you’ll fi nd hundreds more examples of artists’ work, and pick the exhibitions that most appeal to you or are closest to home. From the traditional to the contemporary, and with paintings to pottery, furniture to fashion, textiles, sculpture and more, there’s masses to explore. We hope you are inspired by the pieces on show and fi nd some treasures to take home with you. And remember to keep this guide in a safe place as many of the artists will also be holding Christmas exhibitions. Artweeks is a not-for-profi t organisation and relies upon the generous support of many people to whom we’re most grateful as we bring this celebration of the visual arts to you. In particular we’d like to thank Hamptons International and The Oxford Times for their continued support. -

Slave Housing Data Base

Slave Housing Data Base Building Name: Howard’s Neck, Quarter B Evidence Type: Extant Historical Site Name: Howard's Neck City or Vicinity: Pemberton (near Cartersville, and Goochland C.H.) County: Goochland State: Virginia Investigators: Douglas W. Sanford; Dennis J. Pogue Institutions: Center for Historic Preservation, UMW; Mount Vernon Ladies' Association Project Start: 8/7/08 Project End: 8/7/08 Summary Description: Howards’ Neck Quarter B is a one-story, log duplex with a central chimney and side-gable roof, supported by brick piers, and is the second (or middle) of three surviving currently unoccupied quarters arranged in an east-west line positioned on a moderately western sloping ridge. The quarters are located several hundred yards southwest of the main house complex. The core of the structure consists of a hewn log crib, joined at the corners with v-notches, with a framed roof (replaced), and a modern porch on the front and shed addition to the rear. Wooden siding currently covers the exterior walls, but the log rear wall enclosed by the shed is exposed; it is whitewashed. The original log core measures 31 ft. 9 in. (E-W) x 16 ft. 4 in. (N-S); the 20th-century rear addition is 11 ft. 8 in. wide (N-S) x 31 ft. 9 in. long (E-W). A doorway allows direct access between the two main rooms, which may be an original feature; a doorway connecting the log core with the rear shed has been cut by enlarging an original window opening in Room 1. As originally constructed, the structure consisted of two first-floor rooms, with exterior doorways in the south facade and single windows opposite the doorways in the rear wall. -

U.S. EPA, Pesticide Product Label, ARCH OIT 45, 01/15/2009

c (' UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY ro WASHINGTON, D.C. · 20460 JAN 1 5 2009 &EPA'~;;:IPttiectioo Office of Pesticide Programs Arch Chemical, Inc. 1955 Lake Park Drive, Suite 100 Smyrna, GA 30080 . Attention: Garret B. Schifilliti Senior Regulatory Manager Subject: Arch OIT 45 EPA Registration No. 1258-1323 Your Amendment Dated December 16,2008 This will acknowledge receipt of your notification of changes to the Storage and Disposal Statements for the "Container Rule", submitted under the provisions of FIFRA Section 3(c)(9). Based on a review of the submitted material, the following comments apply. The Notification dated December 18, 2008 is in compliance with PR Notice 98-10 and is acceptable. This Notification has been added to your file. If you have any questions concerning this letter, please contact Martha Terry at (703) 308-6217. Sincerely ~h1'b Marshall Swindell ~ Product Manager (33) Regulatory Management Branch 1 Antimcrobials Division (7510C) ( ( Forrt., _oroved. O. _No. 2070-0060 . emir.. 2·28·95 United States Registration OPP Identifier Number &EPA Environmental Protection Agency Amendment Washington, DC 20460 @.;. Other· Application for Pesticide - Section I 1. Company/Product Number 2. EPA Product Manager 3. Proposed Classification 1258-1323 Marshall Swindell [2] None D Restricted 4. Company/Product (Name) PM' Arch OIT 45 5. Nama and Address of Applicant (Include ZIP Code) 6. Expedited Reveiw. In accordance with FIFAA Section 3(c)(3) Arch Chemicals, Inc. (b)(il. my product is similar or identical in composition and labeling to: 1955 Lake Park Drive EPA Reg. No. ________________________________ Smyrna, GA 30080 D Check if this is a neW address Product Name Section - II Amendment - Explain below. -

The CAMRA Regional Inventory for London Pub Interiors of Special Historic Interest Using the Regional Inventory

C THE CAMPAIGN FOR REAL ALE The CAMRA Regional Inventory for London Pub Interiors of Special Historic Interest Using the Regional Inventory The information The Regional Inventory listings are found on pages 13–47, where the entries are arranged alphabetically by postal districts and, within these, by pub names. The exceptions are outer London districts which are listed towards the end. Key Listed status Statutory listing: whether a pub building is statutorily listed or not is spelled out, together with the grade at which it is listed LPA Local planning authority: giving the name of the London borough responsible for local planning and listed building matters ✩ National Inventory: pubs which are also on CAMRA’s National Inventory of Pub interiors of Outstanding Historic Interest Public transport London is well served by public transport and few of the pubs listed are far from a bus stop, Underground or rail station. The choice is often considerable and users will have no di≤culty in easily reaching almost every pub with the aid of a street map and a transport guide. A few cautionary words The sole concern of this Regional Inventory is with the internal historic fabric of pubs – not with qualities like their atmosphere, friendliness or availability of real ale that are featured in other CAMRA pub guides. Many Regional Inventory pubs are rich in these qualities too, of course, and most of them, but by no means all, serve real ale. But inclusion in this booklet is for a pub’s physical attributes only, and is not to be construed as a recommendation in any other sense. -

California Licensed Contractor ©

WINTER/SPRING 2011 California © Licensed Contractor Stephen P. Sands, Registrar | Edmund G. Brown Jr., Governor 2011 Contracting Laws That Affect You CSLB Has an Licenses for Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) Coming App for That The passage of Senate Bill 392 (and various provisions of the Contractors State License Law CSLB recently including B&P Code Sections 7071.65 and 7071.19) authorizes CSLB to issue contractor launched its new licenses to limited liability companies (LLCs). The law says that CSLB shall begin processing “CSLB mobile” LLC applications no later than January 1, 2012. The LLC will be required to maintain website: www.cslb. liability insurance of between $1,000,000 and $5,000,000, and post a $100,000 surety ca.gov/mobile. bond in addition to the $12,500 bond already required of all licensees. (Senate Bill 392 is CSLB mobile now available at: www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/09-10/bill/sen/sb_0351-0400/sb_392_bill_20100930_ enables users to chaptered.pdf.) check a license, get CSLB office locations, However, do not apply for an LLC license yet; CSLB is not issuing licenses to LLCs at this time. sign up for e-mail alerts, and help report unlicensed activity right from their “smart” CSLB staff is developing new application procedures, creating applications, and putting in phone. place important technology programming changes that are necessary for this new feature. CSLB anticipates that it will be able to accept and process LLC applications late in 2011. “This is an exciting new step for CSLB,” said Registrar Steve Sands. “This application The best way to receive future updates is to sign up for CSLB E-Mail Alerts at www.cslb.ca.gov. -

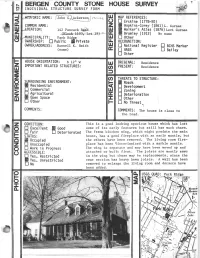

ACCESSIBLE:^^ Byes, Unrestricted

ACCESSIBLE:^^ BYes, Unrestricted CONSTRUCTION DATE/SOURCE: NUMBER OF STORIES: 1-1/2 c. 1770-1810/Architectural evidence CELLAR: B Yes —43 No DC BUILDER: An Ackerson, probably John. CHIMNEY FOUNDATION: O D Stone Arch V) FORM/PLAN TYPE: • Brick Arch, Stone Foundation 111 "F", 5 bay, center hall, 2 rooms deep D Other (32 f 6" x 43'8"). Frame addition Q added as kitchen. FLOOR JOISTS: 6-7" x 9" deep, 23-24" between, 1235-13" floorboards. FRAMING SYSTEM: FIRST FLOOR CEILING HEIGHT: 8'4" ~ In ermed late Bearing Wall FIRST FLOOR WALL THICKNESS: Clear Span 24" L Other GARRET FLOOR JOISTS: Not visible. EXTERIOR MALL FABRIC: GARRET: Well cut red sandstone all around, Unfinished Space except some rubble on west end. B Finished Space ROOF: FENESTRATION: Gable (wing) Not original. 32" x 58" in front, • Gambrel trapezoidal lintels. D Curb D Other ENTRANCE LOCATION/TYPE: EAVE TREATMENT: Plain entrance door in center 37" x 7*5", Sweeping Overhang not original. Supported Overhang (in front) No Overhang D Boxed Gutter D Other This house Is significant for its architecture and its association with the exploration and settlement of the Bergen County, New Jersey area. It is a reasonably well preserved example of the Form/Plan Type as shown and more fully described herein. As such, it is included in the Thematic Nomination to the National Register of Historic Places for the Early Stone Houses of Bergen County, New Jersey. FLOOR PLANS Howard I. Durie believes this house to have been built about 1775 for John G. Eckerson, son of Garret Eckerson, on land Garret and his 0s! cousin Garret Haring purchased on May 4, 1759 from Rev. -

Living Wage Report Urban Vietnam

Living Wage Report Urban Vietnam Ho Chi Minh City With focus on the Garment Industry March 2016 By: Research Center for Employment Relations (ERC) A spontaneous market for workers outside a garment factory in Ho Chi Minh City. Photo courtesy of ERC Series 1, Report 10 June 2017 Prepared for: The Global Living Wage Coalition Under the Aegis of Fairtrade International, Forest Stewardship Council, GoodWeave International, Rainforest Alliance, Social Accountability International, Sustainable Agriculture Network, and UTZ, in partnership with the ISEAL Alliance and Richard Anker and Martha Anker Living Wage Report for Urban Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam with focus on garment industry SECTION I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 3 1. Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 2. Living wage estimate ............................................................................................................ 5 3. Context ................................................................................................................................. 6 3.1 Ho Chi Minh City .......................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Vietnam’s garment industry ........................................................................................ 9 4. Concept and definition of a living wage ........................................................................... -

Download the Resource Guide

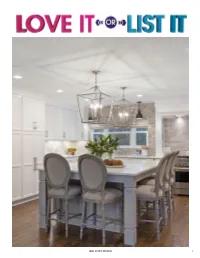

BIG COAT MEDIA 1 MICHAEL + BECKY Michael and Becky loved their sizeable lot and house when they first purchased it six years ago. Unfortunately, the finishes inside the house are artifacts of the 1970’s and their plans to update it have taken a back seat to their busy family life. Michael loves their large family room and bar, but Becky feels the entire floor plan is too cut off for entertaining, and simply dated and dysfunctional. She wants an open concept, updated house for her family and guests, but is determined to find a different house that better suits their needs. Michael is not ready to give up on their huge lot and great neighborhood, and hopes Hilary’s ex- pert designs can bring this time capsule of a house into the 21st century. Becky knows David will find them a house that Michael will love entertaining in for decades to come. BIG COAT MEDIA 2 KITCHEN General Contractor: Kusan Construction Lighting: Generation Lighting - Parker Place Mini Pendants | Savoy House - Townsend Pendants Counter Stools: Aidan Gray - Grace Counter Stools Cabinetry: 1st Choice Cabinetry - Perimeter: Bentley Maple White, Island: Bentley Maple Grit, Recessed Cabinetry: Bentley, Maple Grit | SMJ Cabinetry, LLC. Cabinetry Hardware: Schaub - Heathrow Round Knobs and Pulls Custom Roman Shade: Noble Design Home Studio Tile: Mosaic Home Interiors - Wooden White Honed Premium Marble Quartz: Absolute Stone Corporation - Pure Surfaces Calacatta Oro Quartz Appliances: Garner Appliance & Mattress Plumbing Fixtures: Vault Undermount Sinks, Simplice Faucet, HiRise -

EDWARD MOONEY HOUSE (18 BOWERY BUILDING) 1 Borough of Manhattan

~ndmarks Preservation Commission August 23, 19661 Number 1 LP-D084 EDWARD MOONEY HOUSE (18 BOWERY BUILDING) 1 Borough of Manhattan. Built between 1785 and 1789; architect unknown. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 162, Lot 53. On October 19, 1965, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Edward Mooney House (the 18 Bowery Building) and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site. (Item No, 56). The hearing had been du~ advertised in accordance ~th the provisions of Law. Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS This is the· only know town house surviving in Manhattan which dates from the period of the American Revolution. It was built between 1785 - a scant two years after the British evacuation of the City- and 1789, the year George Washington was inaugurated as first President of the United States and New York City became the first Capital of the nation. The house stands on its original site, at the southeast corner of Pell Street and the Bower,y, and its red brick facade above the street-floor level is in a remarkably good state of preservation, A brick extension, equalling the size of the original structure,. was added in l80J. l The architectural style of the house is EarlY Federal, reflecting strongly its Georgian antecedents in construction, proportions and design details. It is three stories in height, with s finished-garret beneath a gambrel roof, Two features of special note which verif,y the documented age of the building are the hand-hewn timbers framing the roof and the broad width of the front windows in proportion to their height. -

Archaeological Excavations in the City of London 1907

1 in 1991, and records of excavations in the City of Archaeological excavations London after 1991 are not covered in this Guide . in the City of London 1907– The third archive of excavations before 1991 in the City concerns the excavations of W F Grimes 91 between 1946 and 1962, which are the subject of a separate guide (Shepherd in prep). Edited by John Schofield with Cath Maloney text of 1998 The Guildhall Museum was set up in 1826, as an Cite as on-line version, 2021 adjunct to Guildhall Library which had been page numbers will be different, and there are no established only two years before. At first it illustrations in this version comprised only a small room attached to the original text © Museum of London 1998 Library, which itself was only a narrow corridor. In 1874 the Museum transferred to new premises in Basinghall Street, which it was to occupy until Contents 1939. After the Second World War the main gallery was subdivided with a mezzanine floor and Introduction .................................................. 1 furnished with metal racking for the Library, and An outline of the archaeology of the City from this and adjacent rooms coincidentally became the the evidence in the archive ............................. 6 home of the DUA from 1976 to 1981. The character of the archive and the principles behind its formation ..................................... 14 The history of the Guildhall Museum, and of the Editorial method and conventions ................ 18 London Museum with which it was joined in 1975 Acknowledgements ..................................... 20 to form the Museum of London, has been written References .................................................. 20 by Francis Sheppard (1991); an outline of archaeological work in the City of London up to the Guildhall Museum sites before 1973 ........... -

Project Gutenberg's Inns and Taverns of Old London, by Henry C. Shelley

Project Gutenberg's Inns and Taverns of Old London, by Henry C. Shelley Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Inns and Taverns of Old London Author: Henry C. Shelley Release Date: October, 2004 [EBook #6699] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on January 17, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII, with some ISO-8859-1 characters *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK INNS AND TAVERNS OF OLD LONDON *** Produced by Steve Schulze, Charles Franks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. This file was produced from images generously made available by the CWRU Preservation Department Digital Library INNS AND TAVERNS OF OLD LONDON SETTING FORTH THE HISTORICAL AND LITERARY ASSOCIATIONS OF THOSE ANCIENT HOSTELRIES, TOGETHER WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE MOST NOTABLE COFFEE-HOUSES, CLUBS, AND PLEASURE GARDENS OF THE BRITISH METROPOLIS BY HENRY C. -

The Oxford Drinker

Issue 98 December 2016 - January 2017 FREEFREEFREE please take one the Oxford Drinker The free newsletter of the Oxford and White Horse Branches of CAMRA www.oxford.camra.org.uk www.whitehorsecamra.org.uk December 2016 - January 2017 98 2 the Oxford Drinker 98 December 2016 - January 2017 Contents Welcome Gardener’s World 5 Another year is almost 21 Paul Silcock gives a over publican’s view Brewery Focus 6 An in-depth look at Wychwood in Witney A lesson in pubs The OOxfordxford Drinker is the newsletter 8 Pete looks at Oxford’s of the Oxford and White Horse scholastic pubs branches of CAMRA, the Campaign for Real Ale. Tony’s Travels 5000 copies are distributed free of 10 Tony enjoys his visit to charge to pubs across the two Besselsleigh branches’ area, including Oxford, Abingdon, Witney, Faringdon, Hanborough Eynsham, Kidlington, Bampton, 12 Rail Ale Wheatley and Wantage and most of A crawl around the pubs 24 Celebrating 40 years of the villages in between. around Long Hanborough Rail Ale Trips We have recently relaunched our website and pdf downloads are now Pub News available there once again. 14 A round-up of all the latest news locally Editorial team: Editor: Dave Richardson [email protected]@oxford.camra.org.uk Advertising: Tony Goulding [email protected]@oxford.camra.org.uk Tony: 07588 181313 Layout/Design: Matt Bullock Roarsome! Valuable contributions have been 29 Graham Shelton on life at received for this issue from Richard the Red Lion Queralt, Paul Silcock, Dick Bosley, Matt Bullock, Ian Winfield, Dennis Brown, Tony Goulding, Pete Flynn, and Graham Shelton.