Principles of Knife Selection by Christopher Fischer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Machete Fighting in Haiti, Cuba, and Colombia

MEMORIAS Revista digital de Historia y Arqueología desde el Caribe colombiano Peinillas y participación popular: Pelea de machetes en Haiti, Cuba y Colombia 1 Peinillas and Popular Participation: Machete fighting in Haiti, Cuba, and Colombia ∗ Dr. T. J. Desch-Obi Recibido: Agosto 27 de 2009 Aceptado: Noviembre 8 de 2009 RESUMEN: Este artículo explora la historia de esgrima con machetes entre los afro- descendientes en Haití, Cuba y Colombia. El machete, como un ícono sagrado de éxito individual y de guerra en África, se convierte para los esclavizados Africanos en una herramienta usada en la explotación de su trabajo. Ellos retuvieron la maestría en esta arma a través de la extensión del arte de pelea con palos. Esta maestría en las armas blancas ayudó a transformar el machete en un importante instrumento en las batallas nacionales de esas tres naciones. Aún en el comienzo del siglo veinte, el arte de esgrima con machetes fue una práctica social muy expandida entre los Afro-Caucanos, que les permitía demostrar su honor individual, como también hacer importantes contribuciones a las batallas nacionales, como la Colombo-Peruana. Aunque la historia publicada de las batallas nacionales realza la importancia de los líderes políticos y militares, los practicantes de estas formas de esgrima perpetuaron importantes contra- memorias que enfatizan el papel de soldados Afros quienes con su maestría con el machete pavimentaron el camino para la victoria nacional. PALABRAS CLAVES: Esgrima, afro-descendientes, machete. ABSTRACT: This article explores the history of fencing with machetes among people of African descent in Haiti, Cuba, and Colombia. The machete, a sacred icon of individual success and warfare in Africa, became for enslaved Africans a tool used in exploiting their labor. -

Astounding V24n06 (1940 02) (Cape1736)

If This Goes On by Robert Heinlein ” NOTE HOW LISTERINE REDUCED GERMS: The two drawings above illustrate height of range in germ reductions on mouth and throat surfaces in test cases before and after gargling Listerine Antiseptic. Fifteen minutes after gargling, germ reductions up to 96.7% were noted; and even one hour after, germs were still reduced as much as 80%. several industrial plants over 8 years revealed this aston- ishing truth; That those who gargled Listerine Antiseptic twice daily had fewer colds and milder colds than non- users, and fewer sore throats. This impressive record is explained by Listerine Anti- septic’s germ -killing action Listerine Antiseptic reaches way hack on the ... its ability to kill threatening “secondary invad- — throat surfaces to kill "secondary invaders ers” the very types of germs that breed in the mouth and throat and are largely responsible, many . the very types of germs that make a cold authorities say, for the bothersome aspects of a cold. more troublesome. Germ Reductions Up to This prompt and frequent use of full strength 96.7% Listerine Antiseptic may keep a cold from getting Even 15 minutes after Listerine Antiseptic gargle, serious, or head it off entirely. at the time same tests have shown bacterial reductions on mouth and relieving throat irritation when due to a cold. throat surfaces ranging to 96.7%. Up to 80% an hour This is the experience of countless people and it afterward. is backed up by some of the sanest, most impressive In view of this evidence, don’t you think it’s a sen- research work ever attempted in connection with sible precaution against colds to gargle with Listerine cold prevention and relief. -

Download the List of Items to Be Auctioned

Description Description Bicycle 21 speed, red igloo water jug attached Bicycle HUFFY 18 SPEED GIRLS BIKE Bicycle Bicycle Bicycle 24 SPEED ROCKPOINT BICYCLE Bicycle Bicycle Bicycle Trek 800 sport bicycle Bicycle 700 Bicycle Bicycle 20" multi colored bicycle Bicycle girls bike Genesis Illusion Bicycle LIGHT BLUE MAFIABIKES BMX BIKE Bicycle Bicycle Bicycle HYPER SHOCKER 26" MTN BICYCLE Bicycle Shimano Avalon bicycle Bicycle Bicycle Bicycle Schwinn Flight BIKE Bicycle Bicycle Bicycle "B Wipe Out" 8111-69DWA Bicycle Huffy Highland Mountain Bike Bicycle 20" gray boys bike Bicycle Bicycle Bicycle bad condition bike Bicycle HUFFY EVOLUTION BIKE Bicycle 24" white Laguna female style bicycle Bicycle SHADOW Bicycle MGX 12 Speed Bicycle Bicycle RED HUFFY Bicycle Bike W/FRONT BASKET Bicycle Blue Mongoose Camrock Bicycle Bicycle Schwinn High Timber Bicycle HUFFY THUNDER RIDGE BICYCLE Bicycle MONGOOSE 21 SPEED BICYCLE Bicycle RED SCHWINN RADGER Bicycle SCHWINN BIKE Bicycle mens Mt. Bike Bicycle LADIES MOUNTAIN BIKE Bicycle 21 SPEED MOUNTAIN BIKE Bicycle Bicycle Bicycle 12" BOYS XGAMES FS12 Bicycle RADIO FLYER TRICYCLE Bicycle MADD GEAR TWO WHEEL SCOOTER Bicycle MAGNA GIRLS BIKE Bicycle Bicycle Bicycle Pulse PerformancePro Scooter Bicycle RED OLDER MODEL BICYCLE Bicycle HUFFY SUMMIT RIDGE MTN BIKE Bicycle SILVER SCHWINN SKYLINER Bicycle Girls Schwinn Ranger Bicycle Bicycle Next mountain bicycle Bicycle BMX 20" Bicycle Bicycle Bicycle Ultra Terrain model. Bicycle Magna Great Divide 20" Girls Bike Bicycle Model PX6.0 WhtBike Bicycle Bicycle Bicycle Mongoose Revolution Bicycle 26" Kent La Jolla street cruiser bicycle Bicycle BLUE NEXT 15 SPEED BICYCLE Bicycle 20" Mongoose Booster BMX bike Bicycle 7 SPEED 20" BICYCLE Bicycle NEXT TURBO Bicycle GREEN HUFFY TERRAZONE Bicycle Free Spirit outrage mountain bike Bicycle HUFFY STONE MTN MAN'S BICYCLE Bicycle Evolution Pacific Bicycle Bicycle Mt. -

Texas Knifemakers Supply 2016-2017 Catalog

ORDERING AND POLICY INFORMATION Technical Help Please call us if you have questions. Our sales team will be glad to answer questions on how HOW TO to use our products, our services, and answer any shipping questions you may have. You may CONTACT US also email us at [email protected]. If contacting us about an order, please have your 5 digit Order ID number handy to expedite your service. TELEPHONE 1-888-461-8632 Online Orders 713-461-8632 You are able to securely place your order 24 hours a day from our website: TexasKnife.com. We do not store your credit card information. We do not share your personal information with ONLINE any 3rd party. To create a free online account, visit our website and click “New Customer” www.TexasKnife.com under the log in area on the right side of the screen. Enter your name, shipping information, phone number, and email address. By having an account, you can keep track of your order [email protected] history, receive updates as your order is processed and shipped, and you can create notifica- IN STORE tions to receive an email when an out of stock item is replenished. 10649 Haddington Dr. #180 Houston, TX 77043 Shop Hours Our brick and mortar store is open six days per week, except major holidays. We are located at 10649 Haddington Dr. #180 Houston, TX 77043. Our hours are (all times Central time): FAX Monday - Thursday: 8am to 5pm 713-461-8221 Friday: 8am to 3pm Saturday: 9am to 12pm We are closed Sunday, and on Memorial Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day. -

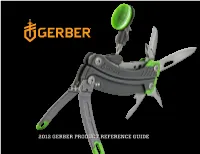

2012 Gerber Product Reference Guide

2012 GERBER PRODUCT REFERENCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PRODUCTS OUTDOOR .............................................................................................................................................. 4 SURVIVAL ......................................................................................................................................... 14 HUNTING .......................................................................................................................................... 35 ESSENTIALS ................................................................................................................................. 54 INDUSTRIAL ................................................................................................................................. 63 TACTICAL ......................................................................................................................................... 68 RETAIL DISPLAYS ..........................................................................................................................75 MERCHANDISE .................................................................................................................................. 77 www.gerbergear.com/germany OUTDOOR CLAM CLAM UPC BOX BOX UPC SPECIFICATIONS HIKING, BIKING, CAMPING, FISHING – WE HAVE A KNIFE OR TOOL FOR EVERY OUTDOOR ACTIVITY. WHEN TESTED IN THE ELEMENTS, GERBER’S OUTDOOR GEAR SHOWS ITS TRUE COLORS - SLEEK, SPORTY DESIGNS CONSTRUCTED WITH RUGGED MATERIALS. DESERTS, MOUNTAINS, FORESTS -

A Guide to Switchblades, Dirks and Daggers Second Edition December, 2015

A Guide to Switchblades, Dirks and Daggers Second Edition December, 2015 How to tell if a knife is “illegal.” An analysis of current California knife laws. By: This article is available online at: http://bit.ly/knifeguide I. Introduction California has a variety of criminal laws designed to restrict the possession of knives. This guide has two goals: • Explain the current California knife laws using plain language. • Help individuals identify whether a knife is or is not “illegal.” This information is presented as a brief synopsis of the law and not as legal advice. Use of the guide does not create a lawyer/client relationship. Laws are interpreted differently by enforcement officers, prosecuting attorneys, and judges. Dmitry Stadlin suggests that you consult legal counsel for guidance. Page 1 A Guide to Switchblades, Dirks and Daggers II. Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................................................................... 1 II. Table of Contents ............................................................................ 2 III. Table of Authorities ....................................................................... 4 IV. About the Author .......................................................................... 5 A. Qualifications to Write On This Subject ............................................ 5 B. Contact Information ...................................................................... 7 V. About the Second Edition ................................................................. 8 A. Impact -

October 2008 Fixed Blade Knives I’Ve Also Heard This Type of Sheath Called the “Wallet Sheath.” Are Extremely Handy, Horsewright Clothing & Tack Co

Hip Pocket Wear Working Hunting Knife The Sunday Dress Knife Remington Shield Adding to the List Bill Rupple 2009 Club Knife They Said What? Legislate Knives Application Form Ourinternational membership is happily involved with “Anything that goes ‘cut’!” October 2008 Fixed blade knives I’ve also heard this type of sheath called the “wallet sheath.” are extremely handy, Horsewright Clothing & Tack Co. offers a wallet sheath very much especially short like the one for the Woodswalker for $45.00 and is designed to hold bladed, compact small short-bladed knives. Of course, if you are at all handy with ones. I am firmly in leather working, making one is a cinch (pun). the camp of those that think anything more The knife on the left is my A.G. Russell Woodswalker. Though the than a 4" blade is hardwood handle that comes with the knife is very nice, I have a bad overkill for most situations. I have a Ruana Smoke Jumper and wear it regularly when working outside or just spending time in the woods. You couldn’t ask for a better short- bladed "belt" knife. Short bladed, under 4", will cut nearly everything that a person needs to cut. However, what if you don’t have a belt onto which to secure that sheath knife? Maybe you’re wearing sweat pants, coveralls or another beltless outfit. Or what if a knife on your belt is a bit too obvious in this politically correct world? Do you grab your folding knife with clip or your neck knife? Though both of these are viable options, I think there is an even better option. -

Cold Steel 1998 Catalog

Performance Warranty We insist all of our knives deliver When it comes to the blade, these include construction. For handles, we strive to develop We stand behind our knives 100%. We extraordinary performance for their asking profile, thickness, blade geometry, edge the perfect mix of materials and ergonomics to subject them to the highest standards in price. In other words, “they must deliver their geometry, steel and heat treatment. Every one offer the most comfortable secure grip available. the industry and strive to make each one moneyʼs worth”. of these factors is studied in great detail to arrive Above all, we TEST what we make! Rigorous as perfect as possible. In order to achieve this goal, we are vitally at the optimum combination for a specific use. testing is the only way to ensure we get the level Our fixed blade sheath knives have a 5 interested in all the elements that are critical to If the knife is a folder, we concentrate on the of performance we demand. year warranty to the original owner against performance. locking mechanism to ensure the strongest, safest defects in materials or workmanship. Our folding knives are warranted for one year. Please remember ANY knife can be broken Tests of Strength & Sharpness or damaged if subjected to sufficient abuse and that all knives eventually wear out (just The Tanto perforating a steel drum. like your boots) and must be replaced. Critics say that practically any knife can Most of the tests shown here be stabbed through a steel drum... but (Right) Retaining a fine edge while are dangerous and they should unlike other knives, the Tantoʼs point is repeatedly cutting pine (wood) not be duplicated. -

The Dilucot Method a Clear Shot at an Excellent Edge

THE DILUCOT METHOD A clear shot at an excellent edge The Dilucot method is unequivocally one of the most artisan ways to sharpen a straight razor. With some experience, results can be obtained that easily withstand comparison with results of high-technological synthetic sharpening setups. Those who went through the learning curve of shaving with a traditional straight razor, know that within the potential advantages of the straight razor also lie its disadvantages. Modern cartridge razors from the supermarket demand little user skill. The traditional straight razor offers us the promise of a perfectly smooth shave that leaves the skin in better condition than any other method, but at the same time, the potential for messing things up is dangerously more present than with modern shaving gear. The same is true for the Dilucot method. It is an acquired skill. At the beginning, expect variable outcomes with peaks and valleys in both directions. The challenge lies in reaching the desired keenness. The legendary smoothness of the Coticule edge arrives free. Don’t expect to meet that keenness at every attempt right from the start. But not to despair, Dilucot honing is not ardu- ous, and even if you don’t get exceptional results, your razor will have an impeccable bevel that needs minimal refinement. For that, you can transition to the final (taped) stages of the Unicot method or rely on a pasted strop. These are both easy ways to get past the sharpness barrier. Note that the latter will replace the characteristic Coticule feel with its own. At its essence, the Dilucot method exemplifies Zen-like sim- The Coticule rock contains billions of spessartine crys- plicity. -

2Ø19 Product Catalogue + +

2Ø19 PRODUCT CATALOGUE + + + + + + + + DEVELOPS PROBLEM SOLVING, LIFE SAVING TOC TOOLS THAT EMPOWER PEOPLE TO BE FISHING 6 UNSTOPPABLE. KNIVES 8 Fixed Blade 8 Assisted Opening 12 Folding 14 Folding Sheath 2Ø Utility 21 MULTI-TOOLS 22 Full Size 22 Compact 26 Mini 26 CUTTING TOOLS 28 Axes 28 Machetes 29 Saws 29 AMERICAN ORIGINAL EQUIPMENT 31 SPIRIT INNOVATOR DISPLAYS 36 INDEX 37 Built through grit, Gerber products GERBERGEAR.COM passion and hard work, challenge the status quo, Gerber’s competitive and bring new solutions spirit is unwavering. to common problems. + BORN ON THE BUILT TO BATTLEFIELD ENDURE Gerber understands trust, Made to save time or and knows great products save the day, Gerber tools can be the difference are built for use and will between life and death. stand the test of time. NEW CONTROLLER™ NEW CROSSRIVER™ FIXED BLADE NEW DEFENDER™ Make short work of messy business. The Controller Fillet Knife is designed for clean, smooth cuts with a flexible The CrossRiver fixed blade is easy to stow on belt or PFD and a quick-release trigger lock deploys with control. The Defender Tether offers a carabiner designed to fit on-finger for intuitive control and a patented line vise blade that provides just the right amount of give. The intuitive GuideFins™ & tactile HydroTread Grip™ offer This utilitarian knife handles varied materials efficiently and is an ideal pick for any adventure, doubling as on each side for secure tension relief. Line is protected by an override lock-out system, and the tool is easily ultimate control of the knife, even in slippery conditions. -

SEAL Pup Knife Boye Knives Swiss Army Champ Knife

SEAL Pup Knife A few years back the SEALs put on a contest for a new knife for military field use. It had to relish salt water, vile chemicals, vile weather, severe use, and non-finesse tasks such as prying open ammunition crates. The winner was a big, tough knife manufac- tured by SOG Knives. It's too big for civilian use— heavy and halfway to a hatchet. So SOG made a version just as tough but in handier size—9 inches long. It's nice to have a working knife that is all tool and no worries. —SB SOG Seal Pup Sheath 9" Knife $70 at www.actiongear.com 800/338-4327 Boye Knives Boye Knives The fancy Boye knives come from a gallery in California. 800-557-1525, I carry a sheath knife everywhere except on air- www.boyeknivesgallery.com planes. People assume a violent or at least self- defense message from the knife, but it has nothing A regular all-metal line can be found at places like to do with that whatever. For opening packages and www.discountknives.com/Boye/Boye.htm envelopes, for stroll-by gardening, for food manage- ment I want a sharp edge in my hand instantly, stow- able instantly (hence a pouch sheath instead of clip- down sheath). It's hard to learn what are the best knives from the knife-fetish magazines because they've agreed never to criticize any knife, and gaudy crap gets From the Web site: lauded along with the actual good stuff. After a few “In 1980, Boye began experimenting with the tech- years of sifting I settled on knives made by David nique of investment casting for making knife blades. -

State V. Harris, No

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF KANSAS No. 116,515 STATE OF KANSAS, Appellee, v. CHRISTOPHER M. HARRIS, Appellant. SYLLABUS BY THE COURT The residual clause "or any other dangerous or deadly cutting instrument of like character" in K.S.A. 2019 Supp. 21-6304 is unconstitutionally vague because it fails to provide an explicit and objective standard of enforcement. Review of the judgment of the Court of Appeals in an unpublished opinion filed January 19, 2018. Appeal from Sedgwick District Court; JOHN J. KISNER, JR., judge. Opinion filed July 17, 2020. Judgment of the Court of Appeals affirming in part and reversing in part the district court is reversed. Judgment of the district court is reversed, and the case is remanded with directions. Kasper C. Schirer, of Kansas Appellate Defender Office, argued the cause, and Kimberly Streit Vogelsberg and Clayton J. Perkins, of the same office, were on the briefs for appellant. Matt J. Maloney, assistant district attorney, argued the cause, and Marc Bennett, district attorney, and Derek Schmidt, attorney general, were with him on the briefs for appellee. The opinion of the court was delivered by STEGALL, J.: In Kansas, it is a crime for a convicted felon to possess a knife. At first blush, the statute appears straightforward. But the statute defines a knife as "a 1 dagger, dirk, switchblade, stiletto, straight-edged razor or any other dangerous or deadly cutting instrument of like character." K.S.A. 2019 Supp. 21-6304. And figuring out when an object is a "knife" because it is a "dangerous or deadly cutting instrument of like character" is not as easy as one might suppose.