The Case of Cairo, Egypt by David Sims

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 Logistics-Related Facilities and Operation: Land Transport

Chapter 4 Logistics-related Facilities and Operation: Land Transport THE STUDY ON MULTIMODAL TRANSPORT AND LOGISTICS SYSTEM OF THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN REGION AND MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT Chapter 4 Logistics-related Facilities and Operation: Land Transport 4.1 Introduction This chapter explores the current conditions of land transportation modes and facilities. Transport modes including roads, railways, and inland waterways in Egypt are assessed, focusing on their roles in the logistics system. Inland transport facilities including dry ports (facilities adopted primarily to decongest sea ports from containers) and to less extent, border crossing ports, are also investigated based on the data available. In order to enhance the logistics system, the role of private stakeholders and the main governmental organizations whose functions have impact on logistics are considered. Finally, the bottlenecks are identified and countermeasures are recommended to realize an efficient logistics system. 4.1.1 Current Trend of Different Transport Modes Sharing The trends and developments shaping the freight transport industry have great impact on the assigned freight volumes carried on the different inland transport modes. A trend that can be commonly observed in several countries around the world is the continuous increase in the share of road freight transport rather than other modes. Such a trend creates tremendous pressure on the road network. Japan for instance faces a situation where road freight’s share is increasing while the share of the other -

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY in CAIRO School of Humanities And

1 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture A thesis on the subject of Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries by Laila Kamal Marei under the supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane 2 Dedications and Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis for my late father; I hope I am making you proud. I am sure you would have enjoyed this field of study as much as I do. I would also like to dedicate this for my mother, whose endless support allowed me to pursue a field of study that I love. Thank you for listening to my complains and proofreads from day one. Thank you for your patience, understanding and endless love. I am forever, indebted to you. I would like to thank my family and friends whose interest in the field and questions pushed me to find out more. Aziz, my brother, thank you for your questions and criticism, they only pushed me to be better at something I love to do. Zeina, we will explore this world of architecture together some day, thank you for listening and asking questions that only pushed me forward I love you. Alya’a and the Friday morning tours, best mornings of my adult life. Iman, thank you for listening to me ranting and complaining when I thought I’d never finish, thank you for pushing me. Salma, with me every step of the way, thank you for encouraging me always. Adham abu-elenin, thank you for your time and photography. -

Ethnic Identity in Graeco-Roman Egypt Instructor

Egypt after the Pharaohs: Ethnic Identity in Graeco-Roman Egypt Instructor: Rachel Mairs [email protected] 401-863-2306 Office hours: Rhode Island Hall 202. Tues 2-3pm, Thurs 11am-12pm, or by appointment. Course Description Egypt under Greek and Roman rule (from c. 332 BC) was a diverse place, its population including Egyptians, Greeks, Jews, Romans, Nubians, Arabs, and even Indians. This course will explore the sometimes controversial subject of ethnic identity and its manifestations in the material and textual record from Graeco-Roman Egypt, through a series of case studies involving individual people and communities. Topics will include multilingualism, ethnic conflict and discrimination, legal systems, and gender, using evidence from contemporary texts on papyrus as well as recent archaeological excavations and field survey projects. Course Objectives By the end of the course, participants should understand and be able to articulate: • how Graeco-Roman Egypt functioned as a diverse multiethnic, multilingual society. • the legal and political frameworks within which this diversity was organised and negotiated. • how research in the social sciences on multilingualism and ethnic identity can be utilised to provide productive and interesting approaches to the textual and archaeological evidence from Graeco-Roman Egypt. Students will also gain a broad overview of Egypt’s history from its conquest by Alexander the Great, through its rule by the Ptolemies, to the defeat of Cleopatra and Mark Antony and its integration into the Roman Empire, to the rise of Christianity. Course Requirements Attendance and participation (10%); assignments (2 short essays of 4-5 pages) and quizzes/map exercises (50%); extended essay on individual topics to be decided in consultation with me (c. -

Ramlet Boulaq Cairo,Egypt

HFC 1425 RAMLET BOULAQ CAIRO,EGYPT What can design do to start to legitimize ramlet boulaq in the eyes of surrounding cairo without denying those existing internal The Nile City Towers sit directly across the street that bounds Ramlet Boulaq on its west relationships? side. The towers have come with a great deal of controversy for the slum dwellers, often bazaar wall fresh food market referring to it as “the shadow they are living under,” as the owner of the towers shares wall a complicated relationship with the slum dwellers. While continually trying to acquire the slum’ s land for his own financial gain, the tower owner has also acknowledged those financial uncertainties at play within the slum as he employed many of Ramlet Boulaq’s residents to act as security for the towers during the 2011 revolution in Cairo. ? ramlet boulaq existing barrier proposed sits condition market 35 ft west of the towers the nile city towers has “Taking me out of here is like taking a fish out its grey water of his pond. I am as loyal to this land as I am serviced 11.4 to my country, Egypt.” These words - spoken by miles away. Mohamed, a Ramlet Boulaq resident - tell the true story of a slum often viewed as ‘something within the shadow.’ The people here value their community above all else. They have fought and will continue to fight for the land that they own and call home. It was crucial to honor these values - these people - when attempting to relieve some of those day to day struggles made worse by those physical living conditions. -

Köppen Signatures” of Fossil Plant Assemblages for Effective Heat Transport of Gulf Stream to Subarctic North Atlantic During Miocene Cooling

Biogeosciences, 10, 7927–7942, 2013 Open Access www.biogeosciences.net/10/7927/2013/ doi:10.5194/bg-10-7927-2013 Biogeosciences © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Evidence from “Köppen signatures” of fossil plant assemblages for effective heat transport of Gulf Stream to subarctic North Atlantic during Miocene cooling T. Denk1, G. W. Grimm1, F. Grímsson2, and R. Zetter2 1Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Palaeobiology, Box 50007, 10405 Stockholm, Sweden 2University of Vienna, Department of Palaeontology, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria Correspondence to: T. Denk ([email protected]) Received: 8 July 2013 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 15 August 2013 Revised: 29 October 2013 – Accepted: 2 November 2013 – Published: 6 December 2013 Abstract. Shallowing of the Panama Sill and the closure 1 Introduction of the Central American Seaway initiated the modern Loop Current–Gulf Stream circulation pattern during the Miocene, The Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum (MMCO) at 17–15 but no direct evidence has yet been provided for effec- million years (Myr) was the last phase of markedly warm cli- tive heat transport to the northern North Atlantic during mate in the Cenozoic (Zachos et al., 2001). The MMCO was that time. Climatic signals from 11 precisely dated plant- followed by the Mid-Miocene Climate Transition (MMCT) bearing sedimentary rock formations in Iceland, spanning at 14.2–13.8 Myr correlated with the growth of the East 15–0.8 million years (Myr), resolve the impacts of the devel- Antarctic Ice Sheet (Shevenell et al., 2004). In the Northern oping Miocene global thermohaline circulation on terrestrial Hemisphere this cooling is reflected by continuous sea ice in vegetation in the subarctic North Atlantic region. -

Effectiveness of Non-Pharmacological Nursing Intervention Program on Female Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis

Cent Eur J Nurs Midw 2017;8(3):682–690 doi: 10.15452/CEJNM.2017.08.0019 ORIGINAL PAPER EFFECTIVENESS OF NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL NURSING INTERVENTION PROGRAM ON FEMALE PATIENTS WITH RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS Eman Ali Metwaly1, Nadia Mohamed Taha1, Heba Abd El-Wahab Seliem2, Maha Desoky Sakr1 1Medical- Surgical Nursing Department, Faculty of Nursing, Zagazig University, Egypt 2Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt Received October 31, 2016; Accepted June 22, 2017. Copyright: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Aim: The aim of study was to evaluate the effectiveness of non-pharmacological nursing intervention programs on female patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Design: A quasi-experimental design was used in this study. Methods: Pre-post follow-up assessment of outcome was used in this study. The study was conducted in the inpatient and outpatient clinics of rheumatology and rehabilitation at Zagazig University Hospitals, Egypt. Results: There was a significant improvement in knowledge and practice of patients with RA in the post and follow-up phase of the program in the intervention group. In addition, the patients showed a high level of independence regarding ability to perform ADL. There was a statistically significant decrease in disability for patients in the intervention group. Conclusion: It is recommended that non-pharmacological intervention programs be implemented for patients with RA in different settings to help reduce the number of patients complaining of pain and disability. Keywords: intervention program, non-pharmacological, rheumatoid arthritis. -

Importers Address Telephone Fax Make(S)

Importers Address Telephone Fax Make(s) Alpha Auto trading Josef tito st. Cairo +20 02-2940330 +20 02-2940600 Citroën cars Amal Foreign Trade Heliopolis, Cairo 11Fakhry Pasha St +20 02-2581847 +20 02-2580573 Lada Artoc Auto - Skoda 2, Aisha Al Taimouria st. Garden city Cairo +20 02-7944172 +20 02-7951622 Skoda Asia Motors Egypt 69, El Nasr Road, New Maadi, Cairo +20 02-5168223 +20 02-5168225 Asia Motors Atic/Arab Trading & 21 Talaat Harb St. Cairo +20 02-3907897 +20 02-3907897 Renault CV Insurance Center of 4, Wadi Al nil st. Mohandessin Cairo +20 02-3034775 +20 02-3468300 Peugeot Development & commerce - CDC - Wagih Abaza Chrysler Egypt 154 Orouba St. Heliopolis Cairo +20 02-4151872 +20 02-4151841 Chrysler Daewoo Corp Dokki, Giza- 18 El-Sawra St. Cairo +20 02-3370015 +20 02-3486381 Daewoo Daimler Chrysler Sofitel Tower, 28 th floor Conish el Nil, +20 02-5263800 +20 02-5263600 Mercedes, Egypt Maadi, Cairo Chrysler Egypt Engineering Shubra, Cairo-11 Terral el-ismailia +20 02-4266484 +20 02-4266485 Piaggio Industries Egyptan Automotive 15, Mourad St. Giza +20 02-5728774 +20 02-5733134 VW, Audi Egyptian Int'l Heliopolice Cairo Ismailia Desert Rd: Airport +20 02-2986582 +20 02-2986593 Jaguar Trading & Tourism / Rolls Royce Jaguar Egypt Ferrari El-Alamia ( Hashim Km 22 First of Cairo - Ismailia road +20 02-2817000 +20 02-5168225 Brouda Kancil bus ) Engineering Daher, Cairo 11 Orman +20 02-5890414 +20 02-5890412 Seat Automotive / SMG Porsche Engineering 89, Tereat Al Zomor Ard Al Lewa +20 02-3255363 +20 02-3255377 Musso, Seat , Automotive Co / Mohandessin Giza Porsche SMG Engineering for Cairo 21/24 Emad El-Din St. -

Exposure Assessment and the Risk Associated with Trihalomethane Compounds in Drinking Water, Cairo

ntal & A me na n ly o t ir ic v a Souaya et al., J Environ Anal Toxicol 2014, 5:1 n l T E o Journal of f x o i l DOI: 10.4172/2161-0525.1000243 c o a n l o r g u y o J Environmental & Analytical Toxicology ISSN: 2161-0525 ResearchResearch Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Exposure Assessment and the Risk Associated with Trihalomethane Compounds in Drinking Water, Cairo – Egypt Eglal R Souaya1, Ali M Abdullah2*, Gouda A RMaatook3 and Mahmoud A khabeer2 1Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Khalifa El-Maamon Street, Cairo, 11566, Egypt 2Holding Company for water and wastewater, IGSR, Alexandria -1125, Egypt 3Central Laboratory of Residue Analysis of Pesticides and Heavy Metals in Foods, Agricultural Research Centre, Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation, Egypt Abstract The main objectives of the study to measure the concentrations of trihalomethanes (THMs) in drinking water of Cairo, Egypt, and their associated risks. Two hundred houses were visited and samples were collected from consumer taps water. Risks estimates based on exposures were projected by employing deterministic and probabilistic approaches. The THMs species (dibromochloromethane, bromoform, chloroform, and bromodichloromethane) ranged from not detected to 76.8 μg/lit. Non-carcinogenic risks induced by ingestion of THMs were exceed the tolerable level (10-6). Data obtained in this research demonstrate that exposure to drinking water contaminants and associated risks were higher than the acceptable level. Keywords: Drinking water; Risk; Trihalomethanes; Cairo routes. In response to the increasing public concern on the pollution of the water supply, this study aims to estimate the THM exposure, Introduction lifetime CR caused by these different routes due to the use of tap water Chlorination, the most commonly used method to disinfect tap in the Cairo, Egypt. -

Final Report on the Journey of 16 Women Candidates

Nazra For Feminist Studies 2 | Nazra for Feminist Studies Nazra for Feminist Studies is a group that aims to build an Egyptian feminist movement, believing that feminism and gender are political and social issues affecting freedom and development in all societies. Nazra aims to mai nstream these values in both public and private spheres. | About Women Political Participation Academy Nazra for Feminist Studies launched the Women Political Participation Academy in October 2011 based on its belief in the importance of women political participation and to contribute in activating women’s role in decision making on different political and social levels. The academy aims to support women’s role in their political participation and to build their capacity and support them in contesting in different elections like the people’s assembly, local councils & trade unions. For more information: http://nazra.org/en/programs/women -political-participation -academy- program | Contact Us [email protected] www.nazra.org | Team This report was written by Wafaa Osama, Advisor of the Women Political Participation Academy (WPPA). She was assisted in r esearch and documentation by Yehia Zayed, the Academy Trainer, and Was em Kamal, Statistical Analyst. Mohammad Sherin Atef, the Academy Consultant, Doaa Abdelaal, Mentoring on the Ground Consultant of the Academy, and Pense Al -Assiouty, Academy Coordinator, contributed to field- work. This report was edited by Mozn Hassan, the Executive Director of Nazra for Feminist Studies. This report was edited and translated into English by Elham Aydarous. | Copyright This report is published under a Creative Common s Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by -nc/3.0 | April 2013 Women Political Participation Academy Nazra For Feminist Studies April 2013 Nazra For Feminist Studies 3 Contents CHAPTER ONE: WOMEN IN PREVIOUS PARLIAMENTS .............................................................................. -

Omar Ashraf Ali Goda Shibin Al Kawm, Al Minufiyah, Egypt - Phone: +201027316772, +201013935495

Omar Ashraf Ali Goda Shibin Al Kawm, Al Minufiyah, Egypt - Phone: +201027316772, +201013935495 Email: [email protected] - Linkedin profile: https://www.linkedin.com/in/omar-ashraf-35384a180 Data of Birth: 1/10/1997 SUMMARY I am self –motivated, ambitious and eager to learn. Looking for both personal and professional growth makes me capable of working under pressure. Seeking for a challenging opportunity to work as an electrical power engineer to enhance my analytic skills and shape my own career. EDUCATION Bachelor’s Degree in Electrical Power and Machines Engineering, Pyramids Higher Institute of Engineering Department: Electrical Engineering Major: Power and Machines Graduation project: (Designed the distribution systems for a population city) Project Grade: Excellent (A+) Graduation Year: 2020 EXPERIENCE Maintenance Engineer , RAYA (from 1 January 2021 to present) Report daily activities to CS TL/ CS SV and service helpdesk. Respond to customers’ calls and fix them based on agreed upon quality standards and customers’ SLAs. Perform new ATM installations, ATM staging or sites inspection and other planned preventive maintenance visits Assist Customer in regards to (training, phone support, onsite support) Close effectively his calls on incidents management system. Keep and maintain all his HW & SW tools in a healthy condition and keep reporting continuously the cases of tools failure or any extra tools needed to his Senior / Team leader. Maintenance Engineer , Police Academy. (from 1 September 2020 to 31 December 2020 -

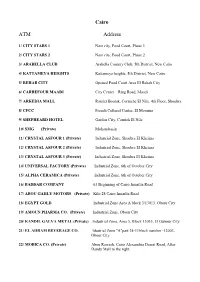

Cairo ATM Address

Cairo ATM Address 1/ CITY STARS 1 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 1 2/ CITY STARS 2 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 2 3/ ARABELLA CLUB Arabella Country Club, 5th District, New Cairo 4/ KATTAMEYA HEIGHTS Kattameya heights, 5th District, New Cairo 5/ REHAB CITY Opened Food Court Area El Rehab City 6/ CARREFOUR MAADI City Center – Ring Road, Maadi 7/ ARKEDIA MALL Ramlet Boulak, Corniche El Nile, 4th Floor, Shoubra 8/ CFCC French Cultural Center, El Mounira 9/ SHEPHEARD HOTEL Garden City, Cornish El Nile 10/ SMG (Private) Mohandessin 11/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 1 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 12/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 2 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 13/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 3 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 14/ UNIVERSAL FACTORY (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 15/ ALPHA CERAMICA (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 16/ BADDAR COMPANY 63 Beginning of Cairo Ismailia Road 17/ ABOU GAHLY MOTORS (Private) Kilo 28 Cairo Ismailia Road 18/ EGYPT GOLD Industrial Zone Area A block 3/13013, Obour City 19/ AMOUN PHARMA CO. (Private) Industrial Zone, Obour City 20/ KANDIL GALVA METAL (Private) Industrial Zone, Area 5, Block 13035, El Oubour City 21/ EL AHRAM BEVERAGE CO. Idustrial Zone "A"part 24-11block number -12003, Obour City 22/ MOBICA CO. (Private) Abou Rawash, Cairo Alexandria Desert Road, After Dandy Mall to the right. 23/ COCA COLA (Pivate) Abou El Ghyet, Al kanatr Al Khayreya Road, Kaliuob Alexandria ATM Address 1/ PHARCO PHARM 1 Alexandria Cairo Desert Road, Pharco Pharmaceutical Company 2/ CARREFOUR ALEXANDRIA City Center- Alexandria 3/ SAN STEFANO MALL El Amria, Alexandria 4/ ALEXANDRIA PORT Alexandria 5/ DEKHILA PORT El Dekhila, Alexandria 6/ ABOU QUIER FERTLIZER Eltabia, Rasheed Line, Alexandria 7/ PIRELLI CO. -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2010 VOLUME I.A / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2010, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 63.350 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance,