Background and Conclusions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brymer Crawshaw Nawton Pukete Flagstaff Sylvester Maeroa Bryant

M R T H A I U V E I E T L S E IN O T C R N K R A R E N E L C ROV E P H G E N O S Y I T A A E E O AN N E E R H D S R S L E T C L V I GAL N E C I E Y E R R V S R I R E Guide to using this map: D R L O A L D Y I A E P E H N E R A E C D A L C E G C E A A A D D R I I V L E S P This is a map of the area containing your property. R E O E C O L R D I C S I C E A A M O N P I V T R L R I H O S L E D E O I T R W R R C L D E H O D C K P M O O S V H O R E S R AVE P A G A VOU NUE E NT N A W C A The map shows notable local changes which are C R E S CE T Y DE R N B E EET R R I E ST VE proposed for the mapped area. E C E L T R IC H E E L A M R R Z N T O IM A N I S A I N U U D P T T P Sylvester H KA TA S H K E P E L S R I A B A S C E E See the map legend for an index of these local O N U P L L E A changes and check the map to see which ones V E C C D A LA R P E T P A E Flagstaff Y S E E U O D IM R U E affect your area of the city. -

Peachgrove Maeroa Swarbrick Clarkin Hamilton East Chartwell

T P E D B A A U A A R L G O W T A N RFIELD C E A AI R R P R A B F E E R O S A A R C S T U R N D D E T T R I E O N S E E O R T T S A R T E Y ESCE T S R NT D C R C L M E S Guide to using this map: E A H E C AT V R R A C E F R Y I I V E S R A H R D E T I E N O E E A S IE R D E V U D N S OA E S A R A Y E I V K S P T D C U C C P L R O C A This is a map of the area containing your property. E A E H C E E T E R Y E E T M N S U D N R T T L E W P O O T E S R R E A A U O R T A L A E N D D A T E E C C A H W A N C L S V E AL T O R V E SH R H A A O N F I R R L R C D A E The map shows notable local changes which are Y S U B A M G B T R S O P E I O A R S E O R R S T R R U L D T Y I N T A L L O O R N A R A T M S O L O L Y L E M S E T C O V IT O N R A H proposed for the mapped area. -

List of Road Names in Hamilton

Michelle van Straalen From: official information Sent: Monday, 3 August 2020 16:30 To: Cc: official information Subject: LGOIMA 20177 - List of road and street names in Hamilton. Attachments: FW: LGOIMA 20177 - List of road and street names in Hamilton. ; LGOIMA - 20177 Street Names.xlsx Kia ora Further to your information request of 6 July 2020 in respect of a list of road and street names in Hamilton, I am now able to provide Hamilton City Council’s response. You requested: Does the Council have a complete list of road and street names? Our response: Please efind th information you requested attached. We trust this information is of assistance to you. Please do not hesitate to contact me if you have any further queries. Kind regards, Michelle van Straalen Official Information Advisor | Legal Services | Governance Unit DDI: 07 974 0589 | [email protected] Hamilton City Council | Private Bag 3010 | Hamilton 3240 | www.hamilton.govt.nz Like us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter This email and any attachments are strictly confidential and may contain privileged information. If you are not the intended recipient please delete the message and notify the sender. You should not read, copy, use, change, alter, disclose or deal in any manner whatsoever with this email or its attachments without written authorisation from the originating sender. Hamilton City Council does not accept any liability whatsoever in connection with this email and any attachments including in connection with computer viruses, data corruption, delay, interruption, unauthorised access or unauthorised amendment. Unless expressly stated to the contrary the content of this email, or any attachment, shall not be considered as creating any binding legal obligation upon Hamilton City Council. -

H201808201.Pdf

:!:!. ~.?.. ~.~ ~ ~ ( ...,,,,.··,.,. -_ .,·.. '.... ......, .... .,.. .... _... ..... ... i33 Molesworth Street PO Box5013 Wellington 6140 New Zealand T +64 4 496 2000 2 2 JAN 2019 Ref: H201808201 Dear Response to your request for official information I refer to your request of 4 December 2018 to the Ministry of Health (the Ministry), under the Official Information Act 1982 (the Act) for: "I would like to request the following information: the total number of pharmacies licenced in New Zealand, and the names and addresses of the pharmacies. This information can be provided in a spreadsheet, showing the: Legal entity name Premises name Street address Suburb City Postcode Region" The information held by the Ministry relating to this request is attached as Appendix One. I trust this information fulfils your request. Please note this response (with your personal details removed) may be published on the Ministry of Health website. Yours sincerely ~~ Derek Fitzgerald Acting Group Manager Medsafe LEGAL ENTITY NAME PREMISES NAME STREET ADDRESS OTHER STREET ADDRESS STREET ADDRESS SUBURB RD STREET ADDRESS TOWN CITY 280 Queen Street (2005) Limited Unichem Queen Street Pharmacy 280 Queen Street Auckland Central Auckland 3 Kings Plaza Pharmacy 2002 Limited 3 Kings Plaza Pharmacy 536 Mount Albert Road Three Kings Auckland 3'S Company Limited Wairoa Pharmacy 8 Paul Street Wairoa 5 X Roads Limited Five Crossroads Pharmacy 280 Peachgrove Road Fairfield Hamilton A & E Chemist Limited Avondale Family Chemist 1784 Great North Road Avondale Auckland A & V -

Kiwi Property and TGH Form Joint Venture at Centre Place North

NZX RELEASE 1 April 2020 Kiwi Property and TGH form joint venture at Centre Place North Kiwi Property and Tainui Group Holdings (TGH) today announced the formation of a 50:50 joint venture over Centre Place North and a selection of adjoining properties. The agreement paves the way for the creation of a mixed-use precinct in the heart of Hamilton’s CBD. Under the terms of the agreement, the joint venture will comprise Centre Place North, 61-65 Bryce Street, 511-523 Victoria Street and land at 10 Ward Street, with a combined value of approximately $71 million. A new 100-year ground lease will be granted by TGH, with rent pre-paid. Kiwi Property CEO Clive Mackenzie said he was looking forward to building on the strong partnership with TGH, which dates back to May 2016, when Kiwi Property acquired a 50% share of The Base. “We’re delighted to be working with TGH to create an exciting new mixed-use destination for the people of the Waikato and beyond. With its pivotal location in the Hamilton CBD, Centre Place North has the potential to bring together an attractive retail, office and perhaps even residential offering. The joint venture with TGH will enable us to move more quickly to deliver this vision,” he said. TGH CEO Chris Joblin said Centre Place North would play an important role in the rejuvenation of Hamilton’s city centre. “We are excited by the potential of this extension of our relationship with Kiwi Property in Kirikiriroa-Hamilton. Building on our experience of working together as co-owners of The Base, we want to bring a 100-year view and some visionary thinking to create something vibrant and special to accelerate the ongoing transformation of the CBD,” Mr Joblin says. -

View Avant • WOF Gib Stoppers, Plasterers, Concreters & Bricklayers Etc 59 Tasman Rd, Hamilton 0800 25 23 25 P

WINDOWS DOORS GLASS Specialists in Laminate Benchtops • Tune Ups • Tyres throughout the Waikato • Lubes • Trailer Hire • Brakes • Wheel Alignments • Gear Boxes • Radiator Repair • Clutch Repairs • Breakdowns • Reconditioning • Free WINZ Quotes Luxury Spa Suites, Free High Speed Wi Fi, 9 Sky Channels Products & Compounds for all Trowel Trades Fairview Avant • WOF Gib Stoppers, Plasterers, Concreters & Bricklayers etc 59 Tasman Rd, Hamilton 0800 25 23 25 P. 07 849 3659 272 Ulster St, Hamilton P: 0800 004 450 10 Karewa Pl, Pukete, Hamilton Contact Steve on 07 849 7745 Ph: 07 838 2733 027 250 0377 [email protected] 58 Bryant Rd, Te Rapa, Hamilton [email protected] www.troweltrades.co.nz 027 258 8672 [email protected] Base for Your Trow [email protected] "Home el Trade" www.fairviewwindows.co.nz www.harkerlaminates.co.nz www.sails-motorinn.co.nz Ln ne R terson Pa ord Dr Osbor Horsham Downs M Develop & print film Rd Heref ENTERPRISE Primary School artin Ln Henderson R 0 Scan film & slides • All Automotive MOTOR GROUP Passport & visa photos Servicing & Repairs to River Trail Photo gifts, frames & albums A 645 Te Rapa Road, HAMILTON w Photo Restoration 1 a • WOF River Rd Shop 11, Five Cross Rds Centre d R aha OPEN 7 DAYS - www.enterprisecars.co.nz LindalesFIS www.lindalephotos.co.nz E: [email protected] P: 07 855 9084 Hamilton t e k u P Close to city centre, restaurants, bars, hospitals, Hors Founders Theatre, sports facilities, shops. Masters Ave Shopping Centre ham Reyno By Hamilton Lake - FREE WiFi, 50+ Channels Sky TV Downs Rd Hillcrest, Hamilton lds Rd Wa ikato Exp 42 Thackeray St, Hamilton Seddon Rd Phone: 07 856 3571 1B re Graham Rd P: 07 839 5553 F: 07 839 5553 ssway Email: [email protected] 1 Kay Rd Rd Kapua Crs E: [email protected] rt Wy Waitihi www.motavation.co.nz Repoiti C www.lakepointmotel.co.nz W Repouni Crt Ha a ncock Rd ir Wai e ka Dr l Ri k a P r ak k l ver Rd D a Pl P aia P rau Arahi ke River To s GREAT SOUND, Down nton Rd Waikato H rdo ors GREAT EVENTS. -

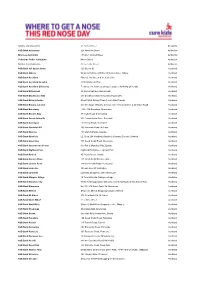

Clinics for Medpro Flu Vouchers – 2020

Clinics for MedPro Flu Vouchers – 2020 To the Voucher Holder: Below is the list for Medical Centres and Pharmacies where you can take your voucher to be redeemed. Your voucher can be redeemed from 1st April, provided the clinic/pharmacy has the flu vaccine in stock. It is best to call the clinic/pharmacy before turning up for your vaccination. The last date for redeeming vouchers is: 30 June 2020. Table: Page 2 – Northland Page 2 – Auckland Page 5 – Waikato Page 6 – Coromandel Page 6 – Bay of Plenty Page 7 – Central Plateau Page 7 – Wanganui and Taranaki Page 7 – Hawkes Bay Page 8 – Wellington Page 9 – Nelson and Marlborough Page 10 – West Coast Page 10 – Canterbury Page 11 – Otago Page 11 – Southland and Fiordland Page 1 Clinics for MedPro Flu Vouchers – 2020 NORTHLAND Unichem Stanmore Bay Pharmacy 570 Whangaparaoa Rd, Stanmore Bay Kerikeri (09) 424 2717 Unichem Kerikeri Pharmacy North Auckland 64 Kerikeri Rd, Kerikeri (09) 407 7144 Life Pharmacy Albany 219 Don McKinnon Drive, Albany, Auckland Whangarei (09) 414 7188 Unichem Kamo Pharmacy Unichem Apollo Pharmacy 521A Kamo Rd, Kamo, Whangarei 119 Apollo Drive, Albany, Auckland (09) 435 0638 (09) 476 9016 Unichem Onerahi Pharmacy Unichem Albany Metro Pharmacy 116 Onerahi Rd, Onerahi, Whangarei 139-163 Don McKinnon Drive, Albany, Auckland (09) 436 0567 (09) 415 1673 Unichem Buchanans Pharmacy Unichem Browns Bay Pharmacy Paramount Plaza, Paramount Parade, Tikipunga 66 Clyde Rd, Browns Bay, Auckland (09) 435 3323 (09) 478 7069 Dargaville Unichem Rosedale Pharmacy 372 Rosedale, Rosedale, Auckland -

Belfast Activity Centre

Christchurch District Plan Review – Commercial Hearing Evidence: Belfast Activity Centre Statement of evidence of Anthony Dominic Dimasi on behalf of PSPIB Waiheke Inc 23 April 2015 MacroPlan Dimasi MELBOURNE SYDNEY Level 4 Level 4 356 Collins Street 39 Martin Place Melbourne VIC 3000 Sydney NSW 2000 (03) 9600 0500 (02) 9221 5211 BRISBANE GOLD COAST Level 15 Level 2 111 Eagle Street 89 – 91 Surf Parade Brisbane QLD 4000 Broadbeach QLD 4218 (07) 3221 8166 (07) 3221 8166 ADELAIDE PERTH Ground Floor Ground Floor 89 King William Street 12 St Georges Terrace Adelaide SA 5000 Perth WA 6000 (08) 8221 6332 (08) 9225 7200 Table of contents Introduction ..............................................................................................i Code of conduct i Experience and expertise i Methodologies, data and information employed iv 1 Scope of evidence ............................................................................1 2 Executive summary ..........................................................................3 3 Belfast Activity Centre – Background ..................................................5 4 Implications for Christchurch Central City Retail Core .......................... 13 5 Implications for Rangiora and Kaiapoi Town Centres ........................... 29 Appendix 1: CV ...................................................................................... 31 Appendix 2: NZ Project Experience ........................................................... 35 This page has been intentionally left blank. Introduction This -

RND Stockists 2017

Smiths City Alexandra 58 Tarbert Street Alexandra ASB Bank Ashburton 228 Havelock Street Ashburton Briscoes Ashburton 160-242 Tancred Street Ashburton Columbus Coffee Ashburton Moore Street Ashburton Smiths City Ashburton 38 Kermode Street Ashburton ASB Bank 125 Queen Street 125 Queen St Auckland ASB Bank Albany Westfield Albany, 219 Don McKinnon Drive, Albany Auckland ASB Bank Auckland Floor G, Cnr Queen & Wellesley Sts Auckland ASB Bank Auckland Hospital 2 Park Road, Grafton Auckland ASB Bank Auckland University Tenancy 128, Business School Complex, Auckland University Auckland ASB Bank Birkenhead 22 Birkenhead Ave, Birkenhead Auckland ASB Bank Blockhouse Bay 519 Blockhouse Bay Road, Blockhouse Bay Auckland ASB Bank Botany Downs Shop PW29, Botany Town Centre, East Tamaki Auckland ASB Bank Botany Junction Unit 38, Stage 2 Botany Junction, Cnr Te Irirangi Drive & Ormiston Road Auckland ASB Bank Broadway 334 - 336 Broadway, Newmarket Auckland ASB Bank Browns Bay 37 Clyde Road, Browns Bay Auckland ASB Bank Constellation Dr 65A Constellation Drive, Rosedale Auckland ASB Bank Devonport 21 Victoria Road, Devonport Auckland ASB Bank Dominion Rd 296 Dominion Road, Mt Eden Auckland ASB Bank Ellerslie 133 Main Highway, Ellerslie Auckland ASB Bank Glenfield L2, Shop 208 Westfield, Bentley & Downing Streets, Glenfield Auckland ASB Bank Greenlane 381 Great South Road, Greenlane Auckland ASB Bank Greenwoods Corner Cnr Pah & Manukau Rds, Epsom Auckland ASB Bank HiGhland Park Highland Park Drive, Highland Park Auckland ASB Bank Howick 85 Picton Street, -

Brymer Crawshaw Nawton Maeroa Dinsdale North Swarbrick Frankton

D OA Guide to using this map: I R K E R E C U A A N L K B TO R T P RO O E K This is a map of the area containing your property. A W R IC A P V N A R E R A E R S A L D O O A G O L R D C IV N E YRLE D E M NE C The map shows notable local changes which are P N LA R A R I B I R C V P O E D A N DRI T E VILIO VE O O E proposed for the mapped area. D K IV R INOGUE R OA A M D U I R R E I I R R ME M AU O TRO G A U K AD VEN A TO UE S R O N See the map legend for an index of these local D E R T R T C I V A R V changes and check the map to see which ones A E M MO T E E O W N U E N N EY U N F E STR E E W E O C ET L V S S A affect your area of the city. U R G D E H P R S L T S C IE A T O L C E R Y G N A E L R A S E L D T A T R D In addition to the mapped local changes, T E N E E RO T TOK there are other proposed changes which may C A URI S ROA E D T E R E affect the area but which are not noted on the C Te Rapa R T IN S L T D R map. -

Hearings Agenda 504 Tuhikaramea Road, Dinsdale, Hamitlon

I hereby give notice that a hearing by commissioners will be held on: Date: Monday, 2 December to Wednesday, 11 December 2013 Time: 9.30am Meeting Room: Council Chambers Venue: Civic Wing, Level 1 Garden Place, HAMILTON HEARINGS AGENDA 504 TUHIKARAMEA ROAD, DINSDALE, HAMITLON COMMISSIONERS Chairperson Mr Doug Arcus Commissioners Mr Alan Watson Contact Name: Mrs S Courtney Telephone: 07 838 6771 Email: [email protected] Website: www.hamilton.co.nz Note: The reports contained within this agenda are for consideration and should not be construed as a decision of Council. Should Commissioners require further information relating to any reports, please contact Hamilton City Council - Democracy. 1 WHAT HAPPENS AT A HEARING At the start of the hearing, the Chairperson will introduce the Commissioners sitting on the hearing panel and council staff and he/she will briefly outline the procedure for the hearing. The Chairperson may then call upon the parties present to introduce themselves to the panel. The Chairperson is addressed as Mr Chairman or Madam Chair. If any party intends to give written or spoken evidence in Maori, the Democracy Advisor must be informed of this at least five working days prior to the Hearing so that a qualified interpreter can be provided. Catering is not provided at the hearing. Scheduling submitters to be heard Approximately one week prior to the hearing, a timetable for all submitters who have returned their hearing attendance form will be prepared. Please note that during the course of the hearing, changing circumstances may mean that the proposed timetable is delayed or brought forward. -

Schools and Schools Zones Relating to a Property 19/01/18 19:29

Schools and schools zones relating to a property 19/01/18 19:29 Schools and schools zones relating to a property The School Report provides detailed information on school zones, from Early Childhood Education through to Tertiary Institutions. Street Address: 74 Wallace Road, Temple View Zoned Schools for this Property Primary / Intermediate Schools ABERDEEN SCHOOL 2.2 km KOROMATUA SCHOOL 3.5 km MAEROA INTERMEDIATE 4.1 km Secondary Schools HAMILTON'S FRASER HIGH SCHOOL 2.6 km Early Childhood Education Dinsdale Kindergarten 84 Bremworth Avenue Distance: 0.9 km Dinsdale 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Free Kindergarten Ph. 07-8478520 Authority: Community Based Tuhikaramea Kohanga Reo 60 Mckay Drive Distance: 1.8 km Temple View 20 Hours Free: Yes Ph. 07-8472457 Type: Te Kohanga Reo Authority: Community Based Waikato Family Homebased Childcare (3) - 2005 Ltd 348 Te Rapa Road Distance: 1.9 km Beerescourt 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Homebased Network Ph. 07-8493049 Authority: Privately Owned Waikato Family Homebased Childcare 2 - 2005 Ltd 348 Te Rapa Road Distance: 1.9 km Beerescourt 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Homebased Network Ph. 07-8493049 Authority: Privately Owned Waikato Family Homebased Childcare 2005 Ltd 348 Te Rapa Road Distance: 1.9 km Beerescourt 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Homebased Network Ph. 07-8493049 Authority: Privately Owned Primary / Intermediate Schools ABERDEEN SCHOOL Aberdeen Drive Distance: 2.1 km Hamilton Decile: 5 Ph. 07 847 7312 Age Range: Contributing Authority: State Gender: Co-Educational School Roll: 656 Zoning: In Zone FRANKTON SCHOOL Massey Street Distance: 2.3 km Dinsdale Decile: 3 http://www.property-guru.co.nz/gurux/render.php?action=ReportChooserAction&report=school&format=html&val_ref=4420%2F1800 Page 1 of 4 Schools and schools zones relating to a property 19/01/18 19:29 Hamilton Age Range: Contributing Ph.