JOHN ALLEN PAULOS Bestselling Author of a MATHEMATICIAM READS the NEWSPAPER And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Allen Jr. Emerges As America's Premier

20 Contents Established in 1902 as The Graduate Magazine FEATURES ‘The Best Beat in Journalism’ 20 How a high school teacher from Hays became America’s top Vatican watcher. BY CHRIS LAZZARINO Happy Together 32 Can families who are truly gifted at being families teach the rest of us how to fashion happier homes? COVER Psychologist Barbara Kerr thinks so. Where the BY STEVEN HILL 24 Music Moves In only three years the Wakarusa Music and Camping Festival has grown from a regional upstart to a national star on the summer rock circuit. BY CHRIS LAZZARINO Cover photo illustration by Susan Younger 32 V olume 104, No. 4, 2006 Lift the Chorus NEW! Hail Harry toured China during the heyday of “pingpong diplomacy,” cur- JAYHAWK Thank you for the arti- rently celebrating its 35th cle on economics anniversary. JEWELRY Professor Harry Shaffer KU afforded many such [“Wild about Harry,” rewarding cosmopolitan experi- Oread Encore, issue No. ences for this western Kansas 3]. As I read the story, I student to meet and learn to fondly recalled taking his know others from distant cul- class over 20 years ago. tures. Why, indeed, can’t we all One fascinating item neg- learn to get along? lected in the article was how Harry Marty Grogan, e’68, g’71 ended up at KU. Seattle Originally a professor at the University of Alabama, he left in disgust Cheers to the engineers when desegregation was denied at the institution. This was a huge loss to The letter from Virginia Treece Crane This new KU Crystal set shimmers Alabama, but an incredible gift to those [“Cool house on Memory Lane,” issue w ith a delicate spark le. -

The City of Newark

TO ALL President’s Message Inductees, Scholarship Recipients, Family and Friends, It is with great honor that I welcome you tonight, to our 30nd Annual Newark Athletic Hall of Fame Induction Dinner. Since 1988, we have been honoring athletes from public and private schools in and around the City of Newark. Our initial purpose was to focus attention on Newark’s glorious past and its bright future by creating a positive environment where friendships, camaraderie and memories can be renewed. Tonight we continue that tradition with eighteen new Inductees and four Scholarship Awardees. The Honorees have proven, as in the past, that they are to be recognized as true role models, a characteristic very much in need these days, whether in a large city or a small town. You can turn to a bio page in this or any one of the previous twenty-nine books of inductees and find a role model you can be proud to emulate. The hallmarks of a good athlete are dedication, desire, teamwork, hard work, time management and good sportsmanship. These are the same qualities necessary to succeed in the classroom and the workplace. That’s why our Hall of Fame Family of Inductees are to be viewed as success stories, on and off the field. To our Scholarship Award Winners, you have been recognized to possess the characteristics outlined above; therefore, we wish you good fortune in college and hope to see you back here one evening on the dais, as a future Inductee into the Hall of Fame. Finally, as Newark has become a hotbed for professional and college sports alike, we must not forget the high school and recreation level athletes and support their efforts. -

2020 Preview Guide

850 Ridge Avenue Suite 301 Pittsburgh, PA 15212 Office: (412) 321-8440 Fax: (412) 321-4088 2020 PREVIEW GUIDE Team Name: Central Connecticut State University Mascot: Blue Devils Location: New Britain, CT Captain(s)/Coach(s): Coach: Nilvio Perez Captains: Dantae Maddock, Mark Garcia, Kevin Griffin 2018-19 Performance (LAST SEASON): Record: 1-13 Final Conference Ranking/World Series Results: N/A Notables: Win against Div 1 in state opponent UConn Fall 2019 Performance (Should it be applicable): 2019 Fall Record (NCBA Sanctioned Games Only): 4-5 Notables: 4-2 in conference play Number of Returning Players (Include conference/league award winners): 25 Players to Watch: Nolan Devivo, Dom Rinaldi, Doug Thorne, Evan Colley New additions: K.J. Burt, Luke Saharek Biggest Rival: First Year in New Conference, do not have a rival yet Best Player Nickname: DOMinant-Dom Rinaldi 2020 Season Outlook: The CCSU Club Baseball team is eyeing their first winning season since joining the NCBA. © 2011 National Club Baseball Association 850 Ridge Avenue Suite 301 Pittsburgh, PA 15212 Office: (412) 321-8440 Fax: (412) 321-4088 2020 PREVIEW GUIDE Team Name: Marist College Mascot: Red Foxes Location: Poughkeepsie, New York Captain(s)/Coach(s): Brandon James 2018-19 Performance (LAST SEASON): ● Record: 4-4 ● Final Conference Ranking: 3rd Place ● Notables: Robert Schardt Fall 2019 Performance (Should it be applicable): ● 2019 Fall Record (NCBA Sanctioned Games Only): 6-5 ● Notables: Matt Byam, Matthew Riemann Number of Returning Players (Include conference/league award winners): 10 Players to Watch: Matthew Byam Ilan Kimel Christopher Betancourt Best Player Nickname: Big Pants, Breadsticks 2020 Season Outlook: We have 6 conference games remaining against St. -

John Allen Paulos Curriculum Vitae – 2016

(Note: This C.V. was originally compiled to conform to a University form, which, like most such institutional templates, is repetitive, clunky, and a little lacking in narrative verve. On the other hand, it is a C.V. and not an autobiography. (For that see my new book - Nov., 2015 – A Numerate Life.) More about me is available on my website at www.math.temple.edu/paulos) John Allen Paulos Curriculum Vitae – 2016 Education, Academic Position: Education: Public Schools, Milwaukee; B.S., University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1967; M.S., University of Washington, 1968; U.S. Peace Corps, 1970; Ph. D. in mathematics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1974. Doctoral Dissertation: "Delta Closed Logics and the Interpolation Property"; 1974; Professor K. Jon Barwise. Positions Held: Temple University Mathematics Department: 1973, Assistant Professor, 1982, Associate Professor, 1987, Full Professor Columbia University School of Journalism 2001, Visiting Professor Nanyang Technological University, summer visitor, 2011-present Awards: My books and expository writing as well as my public talks and columns led to my receiving the 2003 Award for promoting public understanding of science from the American Association for the Advancement of Science. (Previous winners include Carl Sagan, E. O. Wilson, and Anthony Fauci.) I received the 2002 Faculty Creative Achievement Award from Temple University for my books and other writings. My piece "Dyscalculia and Health Statistics" in DISCOVER magazine won the Folio Ovation Award for the best piece of commentary in any American magazine. My books and expository writing as well as my public talks and columns also led to my receiving the 2013 Mathematics Communication Award from the Joint Policy Board of 1 Mathematics. -

A Few Reflections on a Numerate Life

Numeracy Advancing Education in Quantitative Literacy Volume 11 Issue 1 Winter 2018 Article 8 2018 A Few Reflections on A Numerate Life John Allen Paulos Temple University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/numeracy Part of the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Paulos, John A.. "A Few Reflections on A Numerate Life." Numeracy 11, Iss. 1 (2018): Article 8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1936-4660.11.1.8 Authors retain copyright of their material under a Creative Commons Non-Commercial Attribution 4.0 License. A Few Reflections on A Numerate Life Abstract John Allen Paulos. 2015. A Numerate Life: A Mathematician Explores the Vagaries of Life, His Own and Probably Yours (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books). 200 pp. ISBN 978-1633881181. This piece briefly introduces and excerpts A Numerate Life: A Mathematician Explores the Vagaries of Life, His Own and Probably Yours, written by John Allen Paulos and published by Prometheus Books. The book shares observations on life—many biographical—from the perspective of a numerate mathematician. The excerpt uses basic statistical reasoning to explore why we should expect that being odd is a most normal experience. Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Cover Page Footnote John Allen Paulos is Professor of Mathematics at Temple University and the author Innumeracy, A Mathematician Reads the Newspaper, and, most recently, A Numerate Life among other books. His web page is johnallenpaulos.com and his twitter feed is twitter.com@johnallenpaulos This from book authors is available in Numeracy: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/numeracy/vol11/iss1/art8 Paulos: A Few Reflections on A Numerate Life Author’s Reflections: A Numerate Life Lawyers, journalists, economists, novelists, and “public intellectuals,” among others, are all frequent commentators on both contemporary social issues and our personal lives and predicaments. -

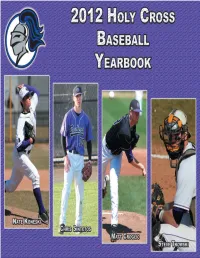

2012 Holy Cross Baseball Yearbook Is Published by Commitment to the Last Principle Assures That the College Secretary:

2 22012012 HOOLYLY CRROSSOSS BAASEBALLSEBALL AT A GLLANCEANCE HOLY CROSS QUICK FACTS COACHING STAFF MISSION STATMENT Location: . .Worcester, MA 01610 Head Coach:. Greg DiCenzo (St. Lawrence, 1998) COLLEGE OF THE HOLY CROSS Founded: . 1843 Career Record / Years: . 93-104-1 / Four Years Enrollment: . 2,862 Record at Holy Cross / Years: . 93-104-1 / Four Years DEPARTMENT OF ATHLETICS Color: . Royal Purple Assistant Coach / Recruiting Coordinator: The Mission of the Athletic Department of the College Nickname: . Crusaders . .Jeff Kane (Clemson, 2001) of the Holy Cross is to promote the intellectual, physical, Affi liations: . NCAA Division I, Patriot League Assistant Coach: and moral development of students. Through Division I President: . Rev. Philip L. Boroughs, S.J. Ron Rakowski (San Francisco State, 2002) athletic participation, our young men and women student- Director of Admissions: . Ann McDermott Assistant Coach:. Jeff Miller (Holy Cross, 2000) athletes learn a self-discipline that has both present and Offi ce Phone: . (508) 793-2443 Baseball Offi ce Phone:. (508) 793-2753 long-term effects; the interplay of individual and team effort; Director of Financial Aid: . Lynne M. Myers E-Mail Address: . [email protected] pride and self esteem in both victory and defeat; a skillful Offi ce Phone: . (508) 793-2265 Mailing Address: . .Greg DiCenzo management of time; personal endurance and courage; and Director of Athletics: . .Richard M. Regan, Jr. Head Baseball Coach the complex relationships between friendship, leadership, Associate Director of Athletics:. Bill Bellerose College of the Holy Cross and service. Our athletics program, in the words of the Associate Director of Athletics:. Ann Zelesky One College Street College Mission Statement, calls for “a community marked Associate Director of Athletics:. -

Birds and Frogs Equation

Notices of the American Mathematical Society ISSN 0002-9920 ABCD springer.com New and Noteworthy from Springer Quadratic Diophantine Multiscale Principles of Equations Finite Harmonic of the American Mathematical Society T. Andreescu, University of Texas at Element Analysis February 2009 Volume 56, Number 2 Dallas, Richardson, TX, USA; D. Andrica, Methods A. Deitmar, University Cluj-Napoca, Romania Theory and University of This text treats the classical theory of Applications Tübingen, quadratic diophantine equations and Germany; guides readers through the last two Y. Efendiev, Texas S. Echterhoff, decades of computational techniques A & M University, University of and progress in the area. The presenta- College Station, Texas, USA; T. Y. Hou, Münster, Germany California Institute of Technology, tion features two basic methods to This gently-paced book includes a full Pasadena, CA, USA investigate and motivate the study of proof of Pontryagin Duality and the quadratic diophantine equations: the This text on the main concepts and Plancherel Theorem. The authors theories of continued fractions and recent advances in multiscale finite emphasize Banach algebras as the quadratic fields. It also discusses Pell’s element methods is written for a broad cleanest way to get many fundamental Birds and Frogs equation. audience. Each chapter contains a results in harmonic analysis. simple introduction, a description of page 212 2009. Approx. 250 p. 20 illus. (Springer proposed methods, and numerical 2009. Approx. 345 p. (Universitext) Monographs in Mathematics) Softcover examples of those methods. Softcover ISBN 978-0-387-35156-8 ISBN 978-0-387-85468-7 $49.95 approx. $59.95 2009. X, 234 p. (Surveys and Tutorials in The Strong Free Will the Applied Mathematical Sciences) Solving Softcover Theorem Introduction to Siegel the Pell Modular Forms and ISBN: 978-0-387-09495-3 $44.95 Equation page 226 Dirichlet Series Intro- M. -

Changing Baseball Forever Jake Sumeraj College of Dupage

ESSAI Volume 12 Article 34 Spring 2014 Changing Baseball Forever Jake Sumeraj College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Sumeraj, Jake (2014) "Changing Baseball Forever," ESSAI: Vol. 12, Article 34. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol12/iss1/34 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sumeraj: Changing Baseball Forever Changing Baseball Forever by Jake Sumeraj (Honors English 1102) idden in the back rooms of any modern major league baseball franchise are a select few individuals that are drastically changing the way teams operate. Using numbers and Hborderline obsessive tracking of each player’s every move, they see things that elude the everyday baseball fan. These are the baseball analysts. Although they do the research that can potentially decide which player becomes the face of the team, these analysts can likely walk the city streets without a single diehard fan knowing who they are. Baseball analysts get almost zero publicity. However, their work is clearly visible at any baseball game. A catcher’s decision to call for a 2-0 curveball to a power hitter, the manager’s choice to continuously play a hitter that’s only batting 0.238, and a defensive shift to the left that leaves the entire right side of the infield open are all moves that are the result of research done by analysts. -

Worlds Apart: How the Distance Between Science and Journalism Threatens America's Future

Worlds Apart Worlds Apart HOW THE DISTANCE BETWEEN SCIENCE AND JOURNALISM THREATENS AMERICA’S FUTURE JIM HARTZ AND RICK CHAPPELL, PH.D. iv Worlds Apart: How the Distance Between Science and Journalism Threatens America’s Future By Jim Hartz and Rick Chappell, Ph.D. ©1997 First Amendment Center 1207 18th Avenue South Nashville, TN 37212 (615) 321-9588 www.freedomforum.org Editor: Natilee Duning Designer: David Smith Publication: #98-F02 To order: 1-800-830-3733 Contents Foreword vii Scientists Needn’t Take Themselves Seriously To Do Serious Science 39 Introduction ix Concise writing 40 Talk to the customers 41 Overview xi An end to infighting 42 The incremental nature of science 43 The Unscientific Americans 1 Scientific Publishing 44 Serious omissions 2 Science and the Fourth Estate 47 The U.S. science establishment 4 Public disillusionment 48 Looking ahead at falling behind 5 Spreading tabloidization 48 Out of sight, out of money 7 v Is anybody there? 8 Unprepared but interested 50 The regional press 50 The 7 Percent Solution 10 The good science reporter 51 Common Denominators 13 Hooked on science 52 Gauging the Importance of Science 53 Unfriendly assessments 13 When tortoise meets hare 14 Media Gatekeepers 55 Language barriers 15 Margin of error 16 The current agenda 55 Objective vs. subjective 17 Not enough interest 57 Gatekeepers as obstacles 58 Changing times, concurrent threats 17 What does the public want? 19 Nothing Succeeds Like Substance 60 A new interest in interaction 20 Running Scared 61 Dams, Diversions & Bottlenecks 21 Meanwhile, -

Jacob Fields Wade, Jr

#A - Jacob Fields Wade, Jr. – Jake “Whistling Jake” Wade By John Fuqua References: SABR MILB Database Baseball Reference The Sporting News Detroit News Joe (Boy) Willis, Carteret County, North Carolina, Baseball Historian “Nuggets on the Diamond”, Dick Dobbins - author In the sandy soil of Carteret County, North Carolina, young boys were schooled in a tough brand of baseball. They emulated their fathers, uncles, and community leaders who held regular jobs during the week in the whaling and fishing community of Morehead City and played baseball in leagues on the weekend. The spirited local nine was tough, smart, scrappy, hard working and on occasion settled slights and disagreements with the area competition with their fists. These men played the game because they loved it. Baseball was not their occupation. It was their avocation. They shared this love with their sons. Jacob Fields Wade, Jr. was born on April 1, 1912 in Morehead City, North Carolina. His father, Jacobs Fields Wade, Sr. had moved to Carteret County in the late 1800’s from Massachusetts. He was a whaler and ship builder and moved to this Southern Coastal Community to build a life for his family. Earlier, he had married Love Styron and together they raised a family of eleven. The four boys were Rupert – who died in an accident, Charles Winfield “Wink”, Jake, and the youngest brother Ben. The daughters were Carita, Maidie, Eudora, Duella, Eleanor, Hazel, and Josephine. Jake Wade attended school at the Charles S Wallace School in Morehead City from 1918-1929. Jake played high school baseball for Wallace, where he started out as a First Baseman because of his height, the coach quickly moved him to the pitching staff as he developed into a dominant pitcher who was difficult to beat. -

The University of Tennessee at Martin

TTHEHE UUNIVERSITYNIVERSITY OOFF TTENNESSEEENNESSEE AATT MMARTINARTIN 22013013 SSKYHAWKKYHAWK BBASEBALLASEBALL 22013013 SSkyhawkkyhawk BBaseballaseball 22013013 UUTT MMARTINARTIN SSKYHAWKKYHAWK BBASEBALLASEBALL ##11 SSonnyonny MMastromatteoastromatteo ##33 JJakeake DDeasoneason ##44 GGrantrant GGlasserlasser ##55 LLuisuis PPaublini-Camposaublini-Campos ##66 SStutu JJonesones ##77 BByronyron JJohannohann ##88 HHagenagen NNelsonelson IIFF • 55-10-10 • 118585 • SSo.o. IIFF • 55-11-11 • 115050 • SSo.o. OOFF • 55-9-9 • 118585 • SSr.r. C • 6-06-0 • 195195 • Fr.Fr. RRHPHP • 66-5-5 • 220202 • JJr.r. OOFF • 66-3-3 • 118585 • SSr.r. CC/IF/IF • 66-4-4 • 118888 • RR-Jr.-Jr. OOrtonville,rtonville, MMich.ich. BBartlett,artlett, TTenn.enn. TTuttle,uttle, OOkla.kla. MMiami,iami, FFla.la. LLexington,exington, TTenn.enn. PPickerington,ickerington, OOhiohio JJackson,ackson, TTenn.enn. ##99 PPhilhil SSorensenorensen ##1010 NicoNico ZychZych ##1212 KyleKyle BargeryBargery ##1313 DDrewrew EErierie ##1414 DDaltonalton PPottsotts ##1515 NNickick WWilsonilson ##1616 WWeses PiersallPiersall IIFF • 66-1-1 • 220808 • Jr.Jr. IIF/RHPF/RHP • 66-0-0 • 117070 • SSo.o. OOFF • 66-1-1 • 118080 • RR-Sr.-Sr. C • 5-95-9 • 155155 • Fr.Fr. LLHPHP • 66-0-0 • 118585 • SSo.o. RRHPHP • 66-2-2 • 222626 • RR-Sr.-Sr. IIF/OFF/OF • 5-85-8 • 160160 • Fr.Fr. EErie,rie, PPa.a. MMonee,onee, IIll.ll. MMunford,unford, TTenn.enn. LLebanon,ebanon, TTenn.enn. GGreenfield,reenfield, TTenn.enn. OOviedo,viedo, FFla.la. MMelbourne,elbourne, FFla.la. ##1717 MMattatt YYoungoung ##1818 BBrentrent MMorrisorris ##1919 JJordanordan SStokestokes ##2020 MMattatt HHaynesaynes ##2323 BBenen BBrewerrewer ##2424 KennyKenny KKinging ##2525 WWadeade CCollinsollins OOFF • 66-1-1 • 117777 • SSr.r. OOFF • 66-1-1 • 220000 • RR-Jr.-Jr. RRHPHP • 66-2-2 • 223939 • RR-Sr.-Sr. -

January 2013 Prizes and Awards

January 2013 Prizes and Awards 4:25 P.M., Thursday, January 10, 2013 PROGRAM SUMMARY OF AWARDS OPENING REMARKS FOR AMS Eric Friedlander, President LEVI L. CONANT PRIZE: JOHN BAEZ, JOHN HUERTA American Mathematical Society E. H. MOORE RESEARCH ARTICLE PRIZE: MICHAEL LARSEN, RICHARD PINK DEBORAH AND FRANKLIN TEPPER HAIMO AWARDS FOR DISTINGUISHED COLLEGE OR UNIVERSITY DAVID P. ROBBINS PRIZE: ALEXANDER RAZBOROV TEACHING OF MATHEMATICS RUTH LYTTLE SATTER PRIZE IN MATHEMATICS: MARYAM MIRZAKHANI Mathematical Association of America LEROY P. STEELE PRIZE FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT: YAKOV SINAI EULER BOOK PRIZE LEROY P. STEELE PRIZE FOR MATHEMATICAL EXPOSITION: JOHN GUCKENHEIMER, PHILIP HOLMES Mathematical Association of America LEROY P. STEELE PRIZE FOR SEMINAL CONTRIBUTION TO RESEARCH: SAHARON SHELAH LEVI L. CONANT PRIZE OSWALD VEBLEN PRIZE IN GEOMETRY: IAN AGOL, DANIEL WISE American Mathematical Society DAVID P. ROBBINS PRIZE FOR AMS-SIAM American Mathematical Society NORBERT WIENER PRIZE IN APPLIED MATHEMATICS: ANDREW J. MAJDA OSWALD VEBLEN PRIZE IN GEOMETRY FOR AMS-MAA-SIAM American Mathematical Society FRANK AND BRENNIE MORGAN PRIZE FOR OUTSTANDING RESEARCH IN MATHEMATICS BY ALICE T. SCHAFER PRIZE FOR EXCELLENCE IN MATHEMATICS BY AN UNDERGRADUATE WOMAN AN UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT: FAN WEI Association for Women in Mathematics FOR AWM LOUISE HAY AWARD FOR CONTRIBUTIONS TO MATHEMATICS EDUCATION LOUISE HAY AWARD FOR CONTRIBUTIONS TO MATHEMATICS EDUCATION: AMY COHEN Association for Women in Mathematics M. GWENETH HUMPHREYS AWARD FOR MENTORSHIP OF UNDERGRADUATE