Voting Without Law?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC Compulsory Voting

Cy-Fair HS Novice Affirmative Case Sept.-Oct 2013- Compulsory Voting “The vote is the most powerful instrument ever devised by man for breaking down injustice and destroying the terrible walls which imprison men because they are different from other men.” Because I agree with these words of former President Lyndon B. Johnson, I stand firmly Resolved: In a democracy, voting ought to be compulsory. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, ought is defined as implying obligation or advisability. Compulsory voting is defined as a system in which electors are obliged to vote in elections or attend a polling place on voting day. If an eligible voter does not attend a polling place, he or she may be subJect to punitive measures.. The value that the affirmative defends is governmental legitimacy. Since a legitimate government must fulfill its obligations to it’s people, a legitimate democracy must strive to be consistent with its core ideals. Thus, the criteria is being consistent with the fundamental characteristics of democracy. As defined in his book Democracy and It’s Critics, Robert Dahl explains that in addition to the concept of “one-person-one-vote”, democracies have four distinguishing characteristics: 1. Effective participation 2. Enlightened understanding of issues 3. Control of the political agenda 4. Inclusiveness Whichever debater’s position is most consistent with these characteristics is being most consistent with democratic legitimacy and should win the debate. 1 Cy-Fair HS Novice Affirmative Case Sept.-Oct 2013- Compulsory Voting My single contention is that compulsory voting is most consistent with the fundamental characteristics of democracy. -

Introduction Voting In-Person Through Physical Secret Ballot

CL 166/13 – Information Note 1 – April 2021 Alternative Voting Modalities for Election by Secret Ballot Introduction 1. This note presents an update on the options for alternative voting modalities for conducting a Secret Ballot at the 42nd Session of the Conference. At the Informal Meeting of the Independent Chairperson with the Chairpersons and Vice-Chairpersons of the Regional Groups on 18 March 2021, Members identified two possible, viable options to conduct a Secret Ballot while holding the 42nd Conference in virtual modality. Namely, physical in-person voting and an online voting system. A third option of voting by postal correspondence was also presented to the Chairpersons and Vice- chairpersons for their consideration. 2. These options have since been further elaborated in Appendix B of document CL 166/13 Arrangements for the 42nd Session of the Conference, for Council’s consideration at its 166th Session under item 13 of its Agenda. During discussions under item 13, Members not only sought further information on the practicalities of adopting one of the aforementioned options but also introduced a further alternative voting option: a hybrid of in-person and online voting. 3. In aiming to facilitate a more informed decision by Members, this note provides additional information on the previously identified voting options on which Members have already received preliminary information, and introduces the possibility of a hybrid voting option by combining in- person and online voting to create a hybrid option. 4. This Information Note further adds information on the conduct of a roll call vote through the Zoom system. Such a vote will be required at the beginning of the Conference for the endorsement of the special procedures outlined in Appendix A under item 3, Adoption of the Agenda and Arrangements for the Session, following their consideration by the General Committee of the Conference at its first meeting. -

The Political Effects of Electronic Voting in India

Technology and Protest: The Political Effects of Electronic Voting in India † Zuheir Desai∗ Alexander Lee April 7, 2019 Abstract Electronic voting technology is often proposed as translating voter intent to vote totals better than alternative systems such as paper ballots. We suggest that electronic voting machines (EVMs) can also alter vote choice, and, in particular, the way in which voters register anti- system sentiment. This paper examines the effects of the introduction of electronic voting machines in India, the world’s largest democracy, using a difference-in-differences methodol- ogy that takes advantage of the technology’s gradual introduction. We find that EVMs are as- sociated with dramatic declines in the incidence of invalid votes, and corresponding increases in vote for minor candidates. There is ambiguous evidence for EVMs decreasing turnout, no evidence for increases in rough proxies of voter error or fraud, and no evidence that machines with an auditable paper trail perform differently from other EVMs. The results highlight the interaction between voter technology and voter protest, and the substitutability of different types of protest voting. Word Count: 9995 ∗Department of Political Science, University of Rochester, Harkness Hall, Rochester, NY 14627. Email: [email protected]. †Department of Political Science, University of Rochester, Harkness Hall, Rochester, NY 14627. Email: alexan- [email protected]. 1 Introduction Social scientists have long been aware that voting technology may have important -

Black Box Voting Ballot Tampering in the 21St Century

This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Black Box Voting — © 2004 Bev Harris Rights reserved to Talion Publishing/ Black Box Voting ISBN 1-890916-90-0. You can purchase copies of this book at www.Amazon.com. Black Box Voting Ballot Tampering in the 21st Century By Bev Harris Talion Publishing / Black Box Voting This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Contents © 2004 by Bev Harris ISBN 1-890916-90-0 Jan. 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form whatsoever except as provided for by U.S. copyright law. For information on this book and the investigation into the voting machine industry, please go to: www.blackboxvoting.org Black Box Voting 330 SW 43rd St PMB K-547 • Renton, WA • 98055 Fax: 425-228-3965 • [email protected] • Tel. 425-228-7131 This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Black Box Voting © 2004 Bev Harris • ISBN 1-890916-90-0 Dedication First of all, thank you Lord. I dedicate this work to my husband, Sonny, my rock and my mentor, who tolerated being ignored and bored and galled by this thing every day for a year, and without fail, stood fast with affection and support and encouragement. He must be nuts. And to my father, who fought and took a hit in Germany, who lived through Hitler and saw first-hand what can happen when a country gets suckered out of democracy. And to my sweet mother, whose an- cestors hosted a stop on the Underground Railroad, who gets that disapproving look on her face when people don’t do the right thing. -

Suppose You Want to Vote Strategically

DONALD SAARI Suppose You Want to Vote Strategically e honest. There have been times when you voted strate- To check, suppose five voters prefer the candidates Anita, Bgically to try to force a personally better election result; Bonnie, and Candy in that order, denoted by ABC, six oth- I have. The role of manipulative behavior received brief ers prefer CBA, and the last four prefer ACB. While it doesnt attention during the 2000 US Presidential Primary Season seem like anything can go wrong, lets check. when the Governor of Michigan failed on his promise to • By voting for one candidate, the commonly used plural- deliver his states Republican primary vote for George Bush. ity system, Anita wins with a 60% landslide; the ACB out- His excuse was that the winner, John McCain, strategically come has the 9:6:0 tally. attracted cross-over votes of independents and Democrats. • Bonnie failed to receive a single plurality vote, yet she McCains strategy was just the accepted behavior of en- wins when each voter votes for her top two candidates couraging supporters who can vote, to vote. But lets pursue where the BCA outcome has the 11:10:9 tally. this issue further; lets question whether the power of math- • Candy? She wins with the procedure offering 5 and 4 ematics can help identify when and how you can strategically points, respectively, to a voters first and second choices; alter the election outcome of your fraternity, sorority, social the CAB outcome has a 46: 45: 44 tally. group, or department to force a personally better conclusion. -

Nber Working Paper Series Valuing the Vote

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES VALUING THE VOTE: THE REDISTRIBUTION OF VOTING RIGHTS AND STATE FUNDS FOLLOWING THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT OF 1965 Elizabeth U. Cascio Ebonya L. Washington Working Paper 17776 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17776 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 January 2012 We thank Bill Fischel, Alan Gerber, Claudia Goldin, Naomi Lamoreaux, Ethan Lewis, Sendhil Mullainathan, Gavin Wright and seminar participants at Dartmouth College, Hunter College and the University of Miami for helpful conversations in preparation of this draft. Cascio gratefully acknowledges research support from Dartmouth College, and Washington gratefully acknowledges research support from the National Science Foundation. All errors are our own. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Elizabeth U. Cascio and Ebonya L. Washington. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Valuing the Vote: The Redistribution of Voting Rights and State Funds Following the Voting Rights Act of 1965 Elizabeth U. Cascio and Ebonya L. Washington NBER Working Paper No. 17776 January 2012, Revised August 2012 JEL No. D72,H7,I2,J15,N32 ABSTRACT The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) has been called one of the most effective pieces of civil rights legislation in U.S. -

Randomocracy

Randomocracy A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Why the B.C. Citizens Assembly recommends the single transferable-vote system Jack MacDonald An Ipsos-Reid poll taken in February 2005 revealed that half of British Columbians had never heard of the upcoming referendum on electoral reform to take place on May 17, 2005, in conjunction with the provincial election. Randomocracy Of the half who had heard of it—and the even smaller percentage who said they had a good understanding of the B.C. Citizens Assembly’s recommendation to change to a single transferable-vote system (STV)—more than 66% said they intend to vote yes to STV. Randomocracy describes the process and explains the thinking that led to the Citizens Assembly’s recommendation that the voting system in British Columbia should be changed from first-past-the-post to a single transferable-vote system. Jack MacDonald was one of the 161 members of the B.C. Citizens Assembly on Electoral Reform. ISBN 0-9737829-0-0 NON-FICTION $8 CAN FCG Publications www.bcelectoralreform.ca RANDOMOCRACY A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Jack MacDonald FCG Publications Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Copyright © 2005 by Jack MacDonald All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2005 by FCG Publications FCG Publications 2010 Runnymede Ave Victoria, British Columbia Canada V8S 2V6 E-mail: [email protected] Includes bibliographical references. -

Spillover from High Profile Statewide Races Into Races

COLLECTIVE AND COMPONENT CONSTITUENCIES: SPILLOVER FROM HIGH PROFILE STATEWIDE RACES INTO RACES FOR THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES by GREGORY J. WOLF (Under the Direction of Jamie L. Carson) ABSTRACT It is widely known that turnout is substantially lower during midterm elections than it is in presidential elections. However, little research has addressed how turnout varies state by state. It is hypothesized that competitive high profile races increase turnout. Additionally, increases in turnout should impact races down the ballot through coattail effects. These hypotheses are tested in on- and off-year elections, expecting different results due to the presence of the presidential race at the top of the ticket in on-years. The results indicate competitive high profile races significantly increase turnout. Additionally, states with same-day voter registration have higher turnout rates than states that do not. Coattails are extended from the presidential race to House races in on-years and from Senate and gubernatorial races in off-years. Surprisingly, Senate races are the only types of races that see enhanced coattail effects when the race is competitive and they are negative in nature. INDEX WORDS: elections, congress, constituency, coattails, turnout COLLECTIVE AND COMPONENT CONSTITUENCIES: SPILLOVER FROM HIGH PROFILE STATEWIDE RACES INTO RACES FOR THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES by GREGORY J. WOLF B.A., The University of Pittsburgh, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Gregory J. Wolf All Rights Reserved COLLECTIVE AND COMPONENT CONSTITUENCIES: SPILLOVER FROM HIGH PROFILE STATEWIDE RACES INTO RACES FOR THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES by GREGORY J. -

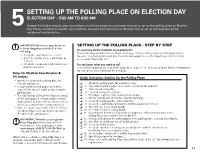

Setting up Polling Place on Election

ELECTION JUDGE/COORDINATOR HANDBOOK | GENERAL ELECTION 2020 CHAPTER 4 SETTING UP THE POLLING PLACE ON ELECTION DAY ELECTION DAY - 5:00 AM TO 6:00 AM Chapter 5 includes step-by-step instructions on all the procedures you need to know to set up the polling place on Election 5 Day. Please review this chapter very carefully. You only have one hour on Election Day to set up and organize all the equipment and materials. IMPORTANT! Before you open the doors SETTING UP THE POLLING PLACE - STEP BY STEP to the polling place, you MUST do the Do you have all the materials and equipment? following: Review the diagram of the ESC in Chapter 4 on page 20 to see where materials and equipment are • Set up the e-poll books (see step 8). located. For a listing of Election Day materials and equipment, see the Supply List (Form 21) in the • Begin the update of the e-poll books by sleeve of the door of the ESC. 5:15 am. • Check the equipment is labeled for your Do you know what you need to do? precinct and ward. First, read the quick overview of all the procedures, steps #1-18. Then, go on to the detailed instructions for each of the steps starting on the next page. Rules for Election Coordinators & All Judges Quick Overview: Setting Up the Polling Place • You MUST report to the polling place by 5:00 am and no later. ❏ 1. Check the polling place for a portable ramp. • Let poll watchers with proper credentials ❏ 2. -

Fresh Perspectives NCDOT, State Parks to Coordinate on Pedestrian, Bike Bridge For

Starts Tonight Poems Galore •SCHS opens softball play- offs with lop-sided victory Today’s issue includes over Red Springs. •Hornets the winners and win- sweep Jiggs Powers Tour- ning poems of the A.R. nament baseball, softball Ammons Poetry Con- championships. test. See page 1-C. Sports See page 3-A See page 1-B. ThePublished News since 1890 every Monday and Thursday Reporterfor the County of Columbus and her people. Thursday, May 12, 2016 Fresh perspectives County school Volume 125, Number 91 consolidation, Whiteville, North Carolina 75 Cents district merger talks emerge at Inside county meeting 3-A By NICOLE CARTRETTE News Editor •Top teacher pro- motes reading, paren- Columbus County school officials are ex- tal involvement. pected to ask Columbus County Commission- ers Monday to endorse a $70 million plan to consolidate seven schools into three. 4-A The comprehensive study drafted by Szotak •Long-delayed Design of Chapel Hill was among top discus- murder trial sions at the Columbus County Board of Com- set to begin here missioners annual planning session held at Southeastern Community College Tuesday Monday. night. While jobs and economic development, implementation of an additional phase of a Next Issue county salary study, wellness and recreation talks and expansion of natural gas, water and sewer were among topics discussed, the board spent a good portion of the four-hour session talking about school construction. No plans The commissioners tentatively agreed that they had no plans to take action on the propos- al Monday night and hinted at wanting more details about coming to an agreement with Photo by GRANT MERRITT the school board about funding the proposal. -

None of the Above: Protest Voting in the World's Largest Democracy*

None Of The Above: Protest Voting in the World’sLargest Democracy Gergely Ujhelyi, Somdeep Chatterjee, and Andrea Szabóy February 29, 2020 Abstract Who are “protest voters” and do they affect elections? We study this question using the introduction of a pure protest option (“None Of The Above”) on Indian ballots. To infer individual behavior from administrative data, we borrow a model from the consumer demand literature in Industrial Organization. We find that in elections without NOTA, most protest voters simply abstain. Protest voters who turn out scatter their votes among many candidates and consequently have little impact on election results. From a policy perspective, NOTA may be an effective tool to increase political participation, and can attenuate the electoral impact of compulsory voting. We thank Sourav Bhattacharya, Francisco Cantú, Alessandra Casella, Aimee Chin, Julien Labonne, Arvind Magesan, Eric Mbakop, Suresh Naidu, Mike Ting, and especially Thomas Fujiwara for useful com- ments and suggestions. We also thank seminar participants at Oxford, Columbia, WUSTL, Calgary, the 2016 Wallis Institute Conference, the 2016 Banff Workshop in Empirical Microeconomics, NEUDC 2016, and the 2016 STATA Texas Empirical Microeconomics conference for comments. Thanks to seminar participants at the Indian Statistical Institute Kolkata, Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, and Public Choice Society 2015 for feedback on an earlier version. We gratefully acknowledge use of the Maxwell/Opuntia Cluster and support from the Center for Advanced Computing and Data Systems at the University of Houston. A previous version of the paper circulated under “‘None Of The Above’Votes in India and the Consumption Utility of Voting”(first version: November 1, 2015). -

Absentee Voting and Vote by Mail

CHapteR 7 ABSENTEE VOTING AND VOTE BY MAIL Introduction some States the request is valid for one or more years. In other States, an application must be com- Ballots are cast by mail in every State, however, the pleted and submitted for each election. management of absentee voting and vote by mail varies throughout the nation, based on State law. Vote by Mail—all votes are cast by mail. Currently, There are many similarities between the two since Oregon is the only vote by mail State; however, both involve transmitting paper ballots to voters and several States allow all-mail ballot voting options receiving voted ballots at a central election office for ballot initiatives. by a specified date. Many of the internal procedures for preparation and mailing of ballots, ballot recep- Ballot Preparation and Mailing tion, ballot tabulation and security are similar when One of the first steps in preparing to issue ballots applied to all ballots cast by mail. by mail is to determine personnel and facility and The differences relate to State laws, rules and supply needs. regulations that control which voters can request a ballot by mail and specific procedures that must be Facility Needs: followed to request a ballot by mail. Rules for when Adequate secure space for packaging the outgoing ballot requests must be received, when ballots are ballot envelopes should be reviewed prior to every mailed to voters, and when voted ballots must be election, based on the expected quantity of ballots returned to the election official—all defer according to be processed. Depending upon the number of ballot to State law.