Bc-3.97 Plus Postage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAST LANSING FILM FESTIVAL PULLOUT PAGE 15 2 City Pulse • October 15, 2014 City Pulse • October 15, 2014 3

FREE A newspaper for the rest of us www.lansingcitypulse.com Oct. 15-21, 2014 a newspaper for the rest of us www.lansingcitypulse.com FREEDOM FIGHTERS, MICHIGAN RESIDENTS JOIN ‘WEEKEND OF RESISTANCE’ - PAGE 5 REVIEW: TONY-WINNER ‘ONCE’ AT THE WHARTON CENTER - page 27 • EAST LANSING FILM FESTIVAL PULLOUT PAGE 15 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • October 15, 2014 City Pulse • October 15, 2014 www.lansingcitypulse.com 3 ENTER TO WIN A 32” FLATSCREEN TV Watch the MSU-UofM game in style! Vote for MSU or Michigan Live remote We'll pick one entry from the team with more votes and donate 1-3 p.m. Friday, Oct. 24, $100 to Breast Cancer Awareness in that person's name. with Dave "Mad Dog" DeMarco Giveaways all week (Oct. 20-25) from 730 AM The Game VOTE FOR MSU OR MICHIGAN MSU UofM Weekdays : 9 a.m.-6 p.m. Saturdays : 9 a.m.-2 p.m. NAME Closed Sundays EMAIL 1001 E. Mt. Hope Ave., Lansing PHONE (corner of Pennsylvania) Your privacy is important to us. We will not share your contact information or email with a 3rd party... EVER. We may occasionally email you with (517) 316-0711 other savings promotions from which you may unsubscribe at any time. 4 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • October 15, 2014 Feedback VOL. 14 ArtPrize is no prize who wish to exhibit their work. There should be ISSUE 9 no qualification, requirements or restrictions. ArtPrize, I found it to be a humorless non- The artistic urge cannot be controlled, forced (517) 371-5600 • Fax: (517) 999-6061 • 1905 E. -

Driving Tour of Historical Sites in Ingham County

s& /r';lio ~ .· Sil-c£/., DRIVING TOUR 11 OF HISTORICAL SITES IN INGHAM COUNTY I NTRaU:r I CN TI1is booklet includes al I properties that have been listed by the National, State and County Register of 1 Historic Places in the County of Ingham. Also listed are the Michigan Centennial Farms, Centennial Businesses and the only tree in the State of Michigan that has attained Bicentennial l..andnark status. TI,is booklet is a record of the sites and structures that are irrportant in the history of Ingham County and i ts deve Iopnent. Sites listed may be evaluated and determined eligible by different qualifications fran the National, State and County levels. Sites are listed alphabetically and sanetimes listed in nx>re than one register. TI1is tour guide to historical sites in the County of Ingham is put out by the Ingham County C,omnission on History in hopes the past can be preserved for future generations. TI,e Ingham County C,omnission on History is the oldest Comnission on History in the State of Michigan. -: ,. · ...;: ..._ 7" ..... · KAPLAN HOUSE TABLE CF ClNTENTS ----- 0 ----- THE RENOVATION OF THE Part 01e: lhe National Register of Historic Places BROWN - PRICE RESIDENCE Part Two: · lhe State Register of Historic Places Part lhree: lhe County Register of Historic Places Part Four: lhe Michigan Centennial Fanns Register Part Five: lhe National Arborist Association and the International Society of Arboriculture Marker --- I j______...___. · 111C~IGAt.J 5TATE RVIATK'I A.')50CIATIOfJ _J Part Six: lhe Historical Society of Michigan Centennial Businesses Register Parrphlet lnfonnation: Ingham County c.omnission on History Author: lhomas G. -

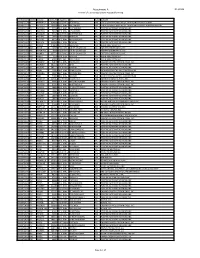

Attachment a DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing

Attachment A DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing File Number Service Callsign Facility ID Frequency City State Licensee 0000072254 FL WMVK-LP 124828 107.3 MHz PERRYVILLE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMN. 0000072255 FL WTTZ-LP 193908 93.5 MHz BALTIMORE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 0000072258 FX W253BH 53096 98.5 MHz BLACKSBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072259 FX W247CQ 79178 97.3 MHz LYNCHBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072260 FX W264CM 93126 100.7 MHz MARTINSVILLE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072261 FX W279AC 70360 103.7 MHz ROANOKE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072262 FX W243BT 86730 96.5 MHz WAYNESBORO VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072263 FX W241AL 142568 96.1 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072265 FM WVRW 170948 107.7 MHz GLENVILLE WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072267 AM WESR 18385 1330 kHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072268 FM WESR-FM 18386 103.3 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072270 FX W289CE 157774 105.7 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072271 FM WOTR 1103 96.3 MHz WESTON WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072274 AM WHAW 63489 980 kHz LOST CREEK WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072285 FX W206AY 91849 89.1 MHz FRUITLAND MD CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. 0000072287 FX W284BB 141155 104.7 MHz WISE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072288 FX W295AI 142575 106.9 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072293 FM WXAF 39869 90.9 MHz CHARLESTON WV SHOFAR BROADCASTING CORPORATION 0000072294 FX W204BH 92374 88.7 MHz BOONES MILL VA CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. -

City Pulse & Top of the Town Top 5

May 16 - 22, 2018 City Pulse & Top of the Town Top 5: Race to the finish See page 13 NOW ON SALE! WHARTONCENTER.COM JULY 11 – 29 1-800-WHARTON Groups (10+): 517- 8 8 4 - 313 0 ©Disney EAST LANSING/ C M Y K 92158 / POP UP TOP COVER STRIP / LANSING CITY PULSE 10.25”W X 2”H RUN DATE: WEDNESDAY, MARCH 21 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • May 16, 2018 • Birthday Parties • Bachelorette Parties COMMUNITY INPUT • Team Building Events • Family Get Together • Girls’ Night Out • Private Party EVENT As McLaren designs its new health care campus adjacent to MSU, we are seeking feedback from the PUBLIC CLASSES community. 7 DAYS A WEEK! Tuesday, May 22 3:30–5 p.m. and 6-7:30 p.m. Lansing Welcome Center got tubs? 2400 Pattengill Ave., Lansing We do! Tons of them! Stop by today! Financing is availble to qualified buyers 2116 E. Michigan Ave. • Lansing, MI 48912 517-364-8827 • www.hotwaterworks.com Mon-Fri 10am - 5:30pm • Sat 10am - 3pm Closed Sunday The Gatekeeper by Maureen B. Gray A powder-coated outdoor sculpture that fits on a 4 x 4 post Available in almost any color, $500.00 It is a charming, happy welcome in any season. Check out the fence sections done by Maureen when you attend the East Lansing Arts Festival. They are installed in the parking lot behind the Peanut Barrel. City Pulse • May 16, 2018 www.lansingcitypulse.com 3 CITY PULSE & LE D BY PFA NTE ESE PR PM 10 JUN E 1ST 5PM LOCAL RESTAURANTS/ BARS COMPETING FOR LANSING’S BEST MARGARITA: AMERICAN FIFTH MICHIGAN’S FIRST MARGARITA FESTIVAL BORDEAUX CHAMPPS LANSING CENTER’S RIVERSIDE PLAZA EL AZTECO EAST HOULIHAN’S LANSING LUGNUTS DON MIDDLEBROOK & JAMMIN’ DJS LA SENORITA MP SOCIAL RADISSON HOTEL TICKETS & MORE INFO AVAILABLE AT: SPIRAL VIDEO & DANCE BAR bit.ly/18margaritafest AND MORE! ADVANCE GA: $25 UNTIL MAY 25! GA: $35 THIS EVENT WOULD ADVANCE VIP: $40 UNTIL MAY 25! VIP: $50 NOT BE POSSIBLE VIP includes special entrance; private tent with freebies, WITHOUT OUR hors d'oeuvres and refreshments! SPONSORS. -

Ferrum Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Letter to Parents and Students .................................................................................... 2 Students’ Rights and Responsibilities ........................................................................ 3 Parental Responsibilities ........................................................................................... 3-4 Guidelines for the Standards of Student Conduct ................................................ 5-14 Laws Regarding the Prosecution of Juveniles as Adults ................................... 15-18 Fees, Fines, and Meal Charges ............................................................................. 18-21 Standards of Student Conduct.............................................................................. 21-24 Attendance and Tardiness .................................................................................... 25-28 Dress Code .................................................................................................................. 29 School Bus Rules and Regulations ...................................................................... 30-34 Acceptable Computer System Use Policy ........................................................... 35-42 State Expulsion Form ................................................................................................. 43 Notice for Directory Information ................................................................................ 44 Notification of Rights under FERPA ......................................................................... -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

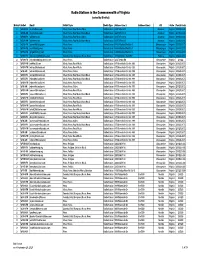

0915 2015 VA Radio Stations.Xlsx

Radio Stations in the Commonwealth of Virginia (sorted by District) District Outlet Email Outlet Topic Media Type Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City State Postal Code 1 WESR-FM [email protected] Music; News; Pop Music; Oldies Radio Station 22479 Front St Accomac Virginia 23301-1641 1 WESR-AM [email protected] Music; News; Pop Music; Rock Music Radio Station 22479 Front St Accomac Virginia 23301-1641 1 WESR-FM [email protected] Music; News; Pop Music; Oldies Radio Station 22479 Front St Accomac Virginia 23301-1641 1 WESR-AM [email protected] Music; News; Pop Music; Rock Music Radio Station 22479 Front St Accomac Virginia 23301-1641 1 WCTG-FM [email protected] Music; News Radio Station 6455 Maddox Blvd Ste 3 Chincoteague Virginia 23336-2272 1 WCTG-FM [email protected] Music; News Radio Station 6455 Maddox Blvd Ste 3 Chincoteague Virginia 23336-2272 1 WCTG-FM [email protected] Music; News Radio Station 6455 Maddox Blvd Ste 3 Chincoteague Virginia 23336-2272 1 WVES-FM [email protected] Country, Folk, Bluegrass; Music; News Radio Station 27214 Mutton Hunk Rd Parksley Virginia 23421-3238 2 WFOS-FM [email protected] Music; News Radio Station 1617 Cedar Rd Chesapeake Virginia 23322 2 WNOR-FM [email protected] Music; News; Rock Music Radio Station 870 Greenbrier Cir Ste 399 Chesapeake Virginia 23320-2671 2 WNOR-FM [email protected] Music; News; Rock Music Radio Station 870 Greenbrier Cir Ste 399 Chesapeake Virginia 23320-2671 2 WJOI-AM [email protected] Music; News; Oldies Radio Station 870 Greenbrier Cir Ste 399 Chesapeake Virginia 23320-2671 -

A Newspaper for the Rest of Us September 6 - 12, 2017 2 City Pulse • September 6, 2017

FREE a newspaper for the rest of us www.lansingcitypulse.com September 6 - 12, 2017 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • September 6, 2017 September Venues Absolute Gallery Arts Council of Greater Lansing Capital City Reprographics Clark Hill PLC Elderly Instruments Grace Boutique of Old Town Great Lakes Artworks Katalyst Gallery Metro Retro MICA Gallery Mother & Earth Baby Boutique Old Town General Store Old Town Marquee Ozone’s Brewhouse Piper & Gold Public Relations SEPTEMBER 8TH 5-8 PM Polka Dots Boutique Retail Therapy Sweet Custom Jewelry Old Town And More! Arts Night Out Arts Night Out returns to Old Town Lansing on September 8, 2017! Experience a variety of unique venues — from the urban core to the outskirts — alive with music, art, demonstrations and a whole lot more. Come explore, meet the artists, wine and dine. Arts Night Out has something for everyone! For more information, visit #MyArtsNightOut www.MyArtsNightOut.com WFMK City Pulse • September 6, 2017 www.lansingcitypulse.com 3 BACK TO SCHOOL MUSIC LESSONS Lansing area’s largest private music school with over 300 students taking lessons each week since 2001. • GUITAR • CLARINET • PIANO • VIOLA • BASS • CELLO • DRUMS • FIDDLE • SINGING • FLUTE • VOICE • VIOLIN • UKULELE LESSONS FOR • SAXOPHONE CHILDREN AND ADULTS Sign up for lessons and receive a $25 registration for FREE! $25.00 517.664.1110 Expires 9/30/17 3444 HAGADORN RD. Limit one per customer, one per household. (at the corner of Hagadorn and Jolly) Cannot be combined with any other oer. LANSINGMUSICLESSONS.COM Coupon must be surrendered at time of registration. Not valid for cash or refunds. -

Virginia NEWS CONNECTION (July–December) 2007 Annual Report

vnc virginia NEWS CONNECTION (July–December) 2007 annual report “Easy to use…Helps provide STORY BREAKOUT NUMBER OF RADIO STORIES STATION AIRINGS* local news…Informative and useful…Could use more Budget Policy & Priorities 1 14 stories on more issues!... Children’s Issues 5 190 Spanish would be good.” Consumer Issues 3 874 Domestic Violence 4 162 Virginia Broadcasters Education 3 129 Endangered Species/Wildlife 1 35 “Virginia News Service Energy Policy 4 157 has catapulted us from Environment 1 60 obscurity, especially in rural Environmental Justice 1 41 areas where we struggled Global Warming/Air Quality 4 170 to gain a foothold. Now our Health Issues 9 2,574 organization is known for Human Rights/Racial Justice 2 69 its work both federally and Hunger/Food/Nutrition 1 50 at the state level by people Livable Wages/Working Families 5 235 who share our concerns.” Peace 1 48 Doug Smith Public Lands/Wilderness 1 42 Virginia Interfaith Center Rural/Farming 5 208 Senior Issues 1 70 Smoking Prevention 3 171 Social Justice 6 3,116 Totals 61 8,415 Launched in July, 2007, the Virginia News Connection produced 61 radio and online news stories, which aired more than 8,415 times on 155 radio stations in Virginia and 1,174 nationwide. * Represents the minimum number of times stories were aired. VIRGINIA RADIO STATIONS City Map # Stations City Map # Stations VNC Market Share Information Altavista 1 WKDE-AM/FM (2) Gloucester 59 WXGM-AM/FM (2) Charlottesville 57% Amherst 2 WAMV-AM Gretna 60 WMNA-AM/FM (2) Frederick, MD 5% Ashland 3 WHAN-AM Harrisonburg -

Noteworthy in August

Radio & TV Program Guide | Aug12 Noteworthy in August n Look for us at August festivals! n Dan Bayer honored at Summer Solstice Jazz Festival n TV membership campaign — August 16-26 n Introducing Peter Whorf College of Communication Arts and Sciences Aug12 A Warm WKAR Welcome to WKAR Peter Whorf Fall Preview Late this month, WKAR will welcome 2012 Peter Whorf as the On Our Cover Thursday, September 6 new WKAR Radio Orangutan Diary is just one WKAR Studio A station manager. Peter Whorf of the new programs viewers Refreshments at 7 p.m. Peter has a Bachelor of Arts degree can support during WKAR-TV's Program begins at 7:30 p.m. August membership campaign, from the Eastman School of Music, August 16-26. and has been the program director for You Are Invited! WNYC and KBIA, the managing pro- WKAR’s Fall Preview event has become ducer for news and talk programming Mark Your an annual tradition. Enjoy a wonderful at Chicago’s WBEZ and most recently Calendars! evening at WKAR with a sneak peek at WFMT/Chicago as program director at the new seasons for radio, televi- and vice president for content. Lansing Jazz Fest sion and online programming – and August 3-4 Gary Reid, WKAR’s general manager, delicious treats to accompany it all! said, “His references from around the The Great Lakes This year’s Fall Preview will introduce country were generous in their praise.” Folk Festival you to the men and women who will ”Peter is astonishingly creative and August 10-12 be participating in our first Quiz- leads by example,” said one. -

MHPN’S Silver Anniversary Year

Silver Anniversary 1981-2006 “Celebrate what’s been accomplished. Think big about what’s to come.” The Michigan Historic Preservation Network and its co-hosts Mark S. Meadows, Mayor of the City of East Lansing, and Lou Anna K. Simon, President of Michigan State University, present the Inaugural Event of the MHPN’s Silver Anniversary Year 25th Annual Michigan Historic Preservation Conference Thursday – Saturday, April 14-16, 2005 East Lansing Hannah Community Center, 819 Abbott Road, East Lansing, Michigan Honorary Chair: Jennifer M. Granholm Governor of Michigan Special Features: •Free Thursday night Community Open House that welcomes area residents and students to join conference participants for an evening that includes the Annual Vendors’ Showcase and more… •7th Annual Construction Trades Symposium – Thursday and Friday… •Friday afternoon Keynote Address by Eugene C. Hopkins, FAIA, Immediate Past President, American Institute of Architects… •Friday evening Annual Preservation Awards Reception and Ceremony at the Kellogg Hotel & Conference Center on the campus of Michigan State University… •Saturday morning program for members of Historic District Commissions and Historic District Study Committees as well as home owners… Get your taxes done EARLY so you can attend! Welcome! Overview and who should attend: Thursday and Friday: We invite you to attend the Michigan Historic Preservation Network’s th Track A – “Preservation Creates Cool” Track – for elected and appointed 25 Annual Statewide Preservation Conference. It serves as the community officials, government staff, those in private business, and individuals Inaugural Event for the MHPN’s entire Silver Anniversary Year that who want to know more about the latest initiatives that make historic starts now and continues into 2006. -

20190404-145033-2015-07-01.Pdf

FREE A newspaper for the rest of us www.lansingcitypulse.com July 1-7, 2015 a newspaper for the rest of us www.lansingcitypulse.com ETHICS ON EDGE PLAN MAY GET CITY COURT CHALLENGE - P. 5 And the nominees are... City Pulse announces 2014-15 Pulsar nominatioNS - P. 9 page 11 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • July 1, 2015 37 PUBLIC NOTICES NOTICE OF DAY OF REVIEW OF APPORTIONMENTS Ingham County Drain Commissioner Patrick E. Lindemann FERLEY CONSOLIDATED DRAIN NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that on Wednesday, July 8, 2015, the apportionments for benefits to the lands comprised within the “Ferley Consolidated Drain Special Assessment District" will be subject to review for one day from 9:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m. at the Ingham County Drain Commissioner’s Office, located at 707 Buhl Avenue, Mason, Michigan 48854. At the meeting to review the apportionment of benefits, I will have the tentative apportionments against parcels and the municipality within the drainage district available to review. At said review, the computation of costs for the Drain will also be open for inspection by any interested parties. There will be no construction as part of this petition and therefore there will not be a notice of letting of drain contract as described Newsmakers in Section 154 of the Michigan Drain Code of 1956. THIS WEEK: Pursuant to Section 155 of the Michigan Drain Code of 1956, any owner of land within the DETROIT drainage district or any city, village, township, district, or county feeling aggrieved by the apportionment HOSTED BY BERL SCHWARTZ of benefits made by the Drain Commissioner may appeal the apportionment within ten (10) days after RESCUE the day of review of apportionments by making an application to the Ingham County Probate Court MISSION for the appointment of a Board of Review.