Below Deck on the “Love Boat”: Intimate Relationships Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

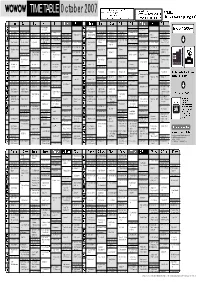

October 2007 TIME TABLE

TIME TABLE October 2007 15 Railway Story*5 00 Henri Cartier- 15 Kojo no Manazashi Bresson: The *5 40 The IT Crowd*4 30 30 Days*5 15 Hits Seeker*3 00 The IT Crowd*4 Impassioned Eye*1 15 Railway Story*5 15 15 Pocahontas : 00 Hollywood Express*5 15 Hits Seeker*3 15 Hits Seeker*3 15 Railway Story*5 15 00 The IT Crowd*4 30 DuckTails*4 30 DuckTails*4 30 DuckTails*4 30 DuckTails*4 30 Bill's Food*5 Snake Eyes*1 Journey to a New 30 DuckTails*4 30 DuckTails*4 30 DuckTails*4 30 Bill's Food*5 The 30 DuckTails*4 00 POCOYO*4 00 POCOYO*4 00 POCOYO*4 00 POCOYO*4 15 Premiere*5 00 Criminal Minds*4 World*1 00 POCOYO*4 00 POCOYO*4 00 POCOYO*4 15 Premiere*5 00 Criminal Minds*4 Benchwarmers*1 00 POCOYO*4 20 20 20 20 The Producers 30 77 Sunset Strip*4 50 Hits Seeker*3 40 20 Kekexili:Mountain 20 Takarazuka Premiere*5 20 Jingle All the Way 30 77 Sunset Strip*3 20 The Bad News Rock School*5 Rock School*5 Typhoon*1 (1968)*1 00 The Unit*4 00 Railway Story*5 A Few Good Men Patrol*1 00 Takarazuka eno *1 00 The Unit*4 00 Railway Story*5 Bears(1976)*1 50 Hits Seeker*3 30 Yokomizo Seishi Series*4 *1 Shotai*5 30 Yokomizo Seishi Series*4 20 00 00 30 Days*5 20 Rock School*5 00 Sleeping with the 00 CSI : Miami*4 00 00 20 Rock School*5 00 Grey's Anatomy 00 CSI : Miami*4 05 Breakfast on Pluto Hide and Seek*1 30 Little Britain*4 50 Enemy*1 Into the Blue*1 30 Rent*1 Soshuhen*4 Bad News Bears *1 00 Dreamer: Inspired Amidado Dayori 20 Daisy 00 Cold Case *4 00 Solntse*1 20 00 00 Cold Case *4 (2005)*1 45 Hits Seeker*3 By a True Story *1 Another Version 50 The Juror*1 My Girl and I*1 Run*1 50 UEFA EURO 2008 00 *1 *1 Birth*1 00 00 25 Hits Seeker*3 Qualifying 00 30 Little Britain*4 One Fine Day Red Eye*1 One Fine Day 40 40 40 Italy vs. -

BAHAMAS: the Love Boat's New Chocolate Voyage 02/12/2016

2/12/2016 BAHAMAS: The Love Boat’s New Chocolate Voyage : Holiday Goddess, Travel for Less BAHAMAS: The Love Boat’s New Chocolate Voyage By Vicki Arkoff Categories Caribbean Islands, Cruises, Destinations, Florida, Food and drink, Ft. Lauderdale, The Bahamas All aboard for the sweet life with Princess Cruises’ new cocoa temptations. Regal Princess Hurricane season aside, the balmy Caribbean is always enticing, especially during the throes of a chilly USA winter. But Princess Cruises really knocked my thermal socks off when I boarded their newest ship, the huge 3,600passenger Regal Princess, to embark on the maiden voyage of the dramatically expanded “Chocolate Journeys” program. Yep, it’s all about chocolate, 24/7, and it’s the most expansive gourmet desserts program on the ocean. Impressively, the endeavor is spearheaded by one of the world’s top master chocolatiers, Norman Love, the former Godiva specialty chocolatier whose Norman Love Confections team now produces 55,000 handpainted, gourmet chocolate candies on a daily basis. (Love on the Love Boat. It’s a match made in sweet heaven.) To celebrate Princess Cruise’s 50th anniversary, Norman Love worked with the cruise line to create a new onboard experience that includes premium chocolate offerings for desserts, cocktails, candy making demos, chocolate/wine tastings, turndown service pillow treats, and even spa treatments at the ship’s Lotus Spa. By the end of 2016, it’ll be available throughout the 18ship fleet. http://www.holidaygoddess.guide/destinations/bahamastheloveboatsailstochocolateparadise/ 1/5 2/12/2016 BAHAMAS: The Love Boat’s New Chocolate Voyage : Holiday Goddess, Travel for Less Master Chocolatier Norman Love. -

Gesamtkatalog BRD (Regionalcode 2) Spielfilme Nr. 94 (Mai 2010)

Gesamtkatalog BRD (Regionalcode 2) Spielfilme -Kurzübersicht- Detaillierte Informationen finden Sie auf unserer Website und in unse- rem 14tägigen Newsletter Nr. 94 (Mai 2010) LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS Talstr. 11 - 70825 Korntal Tel.: (0711) 83 21 88 - Fax: (0711) 8 38 05 18 INTERNET: www.laserhotline.de e-mail: [email protected] Katalog DVD BRD (Spielfilme) Nr. 94 Mai 2010 (500) Days of Summer 10 Dinge, die ich an dir 20009447 25,90 EUR 12 Monkeys (Remastered) 20033666 20,90 EUR hasse (Jubiläums-Edition) 20009576 25,90 EUR 20033272 20,90 EUR Der 100.000-Dollar-Fisch (K)Ein bisschen schwanger 20022334 15,90 EUR 12 Uhr mittags 20032742 18,90 EUR Die 10 Gebote 20000905 25,90 EUR 20029526 20,90 EUR 1000 - Blut wird fließen! (Traum)Job gesucht - Will- 20026828 13,90 EUR 12 Uhr mittags - High Noon kommen im Leben Das 10 Gebote Movie (Arthaus Premium, 2 DVDs) 20033907 20,90 EUR 20032688 15,90 EUR 1000 Dollar Kopfgeld 20024022 25,90 EUR 20034268 15,90 EUR .45 Das 10 Gebote Movie Die 120 Tage von Bottrop 20024092 22,90 EUR (Special Edition, 2 DVDs) Die 1001 Nacht Collection – 20016851 20,90 EUR 20032696 20,90 EUR Teil 1 (3 DVDs) .com for Murder 20023726 45,90 EUR 13 - Tzameti (k.J.) 20006094 15,90 EUR 10 Items or Less - Du bist 20030224 25,90 EUR wen du triffst 101 Dalmatiner (Special [Rec] (k.J.) 20024380 20,90 EUR Edition) 13 Dead Men 20027733 18,90 EUR 20003285 25,90 EUR 20028397 9,90 EUR 10 Kanus, 150 Speere und [Rec] (k.J.) drei Frauen 101 Reykjavik 13 Dead Men (k.J.) 20032991 13,90 EUR 20024742 20,90 EUR 20006974 25,90 EUR 20011131 20,90 EUR 0 Uhr 15 Zimmer 9 Die 10 Regeln der Liebe 102 Dalmatiner 13 Geister 20028243 tba 20005842 16,90 EUR 20003284 25,90 EUR 20005364 16,90 EUR 00 Schneider - Jagd auf 10 Tage die die Welt er- Das 10te Königreich (Box 13 Semester - Der frühe Nihil Baxter schütterten Set) Vogel kann mich mal 20014776 20,90 EUR 20008361 12,90 EUR 20004254 102,90 EUR 20034750 tba 08/15 Der 10. -

Lyric Ramsey Resume 2017

[email protected] // 310-722-0174 Member of the Motion Picture Editors Guild - IATSE Local 700 SUPERVISING EDITOR On Tour With / BET / Entertainment One / Documentary Sisterhood Of Hip Hop Season 3 / Oxygen / 51 Minds / Doc-series Sisterhood Of Hip Hop Season 2 / Oxygen / 51 Minds / Doc-series LEAD EDITOR Grand Hustle/ BET / Endemol/ Competition-Reality Born This Way/ Scripted - Comedy She Got Game / VH1 / 51 Minds / Competition-Reality Suave Says / VH1 / 51 Minds / Doc-series Weave Trip / VH1 / 51 Minds / Doc-series EDITOR Below Deck 5/ Bravo / 51 Minds / Doc-series The Pop Game / Lifetime / Intuitive Entertainment / Competition-Reality Project Runway Juniors 2 / Lifetime / The Weinstein Company / Competition-Reality Below Deck Med / Bravo / 51 Minds / Doc-series Below Deck 4/ Bravo / 51 Minds / Doc-series Project Runway Juniors / Lifetime / The Weinstein Company / Competition-Reality Workout NY / Bravo / All3Media / Doc-series The Singles Project / Bravo / All3Media / Documentary *2015 Emmy Winner for Outstanding Creative Interactive Show Same Name / CBS / 51 Minds / Doc-series Marrying the Game Season 3 / VH1 / 51 Minds / Doc-series LA Hair Season 3 / WeTv / 3Ball Productions / Eyeworks / Doc-series Mind of a Man / GSN / 51 Minds / Game Show Scrubbing In / MTV / 51 Minds / Doc-series Heroes of Cosplay / SyFy / 51 Minds / Competition-Reality LA Hair Season 2 / WeTv / 3Ball Productions / Eyeworks / Doc-series Full Throttle Saloon / TruTV / A. Smith & Co. / Doc-series Finding Bigfoot / APL / Ping Pong Productions / Doc-series Trading -

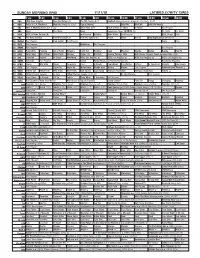

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

Discovery HD World September 2012 Program Schedule

Discovery HD World September 2012 Program Schedule 08/31/2012 05:00 Rhythm And Blooms 2 06:00 Hotels Episode 9 Portugal 05:30 Rhythm And Blooms 2 07:00 East to West Episode 10 Episode 3 06:00 Hotels 08:00 The Alaska Experiment French Polynesian Hotels Starving In The Wilderness 07:00 Travel Wild 09:00 I Have Seen The Earth Change Eco East Coast Vietnam: The Wrath Of The Monsoon 07:30 Travel Wild 10:00 Green Paradise Marine Encounters Brazil - A Preserved Beauty 08:00 A Country Imagined 10:30 Green Paradise Episode 4 Mexico - A Desert Between Two Seas 09:00 Nature's Deadliest 11:00 Fish Life 2 10:00 Nature's Deadliest Episode 5 Africa 11:30 Fish Life 2 11:00 Nature's Deadliest Episode 6 Brazil 12:00 East to West 12:00 Nature's Deadliest Episode 4 Afria II 13:00 A Country Imagined 13:00 Who Survivied? Episode 4 14:00 HMS Ark Royal 14:00 Hotels The Final Journey French Polynesian Hotels 15:00 Mighty Planes 15:00 The Alaska Experiment Airbus A380 Back From The Wild 16:00 Travel Wild 16:00 Rhythm And Blooms 2 Eco East Coast Episode 9 16:30 Travel Wild 16:30 Rhythm And Blooms 2 Marine Encounters Episode 10 17:00 A Country Imagined 17:00 HMS Ark Royal Episode 4 The Final Journey 18:00 A Year In The Wild 18:00 Mighty Planes Episode 2 Airbus A380 19:00 Fun Asia 3 19:00 World's Toughest Expeditions With James Cracknell Queensland 1 Gold Rush 20:00 Discovery Atlas 20:00 Green Paradise 2 Discovery Atlas: China Revealed Indonesia 21:30 An Inside Look 20:30 Green Paradise 2 An Inside Look: Gold - From The Center Of The Earth To Madison Australia Avenue -

From the on Inal Document. What Can I Write About?

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 470 655 CS 511 615 TITLE What Can I Write about? 7,000 Topics for High School Students. Second Edition, Revised and Updated. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-5654-1 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 153p.; Based on the original edition by David Powell (ED 204 814). AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock no. 56541-1659: $17.95, members; $23.95, nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS High Schools; *Writing (Composition); Writing Assignments; *Writing Instruction; *Writing Strategies IDENTIFIERS Genre Approach; *Writing Topics ABSTRACT Substantially updated for today's world, this second edition offers chapters on 12 different categories of writing, each of which is briefly introduced with a definition, notes on appropriate writing strategies, and suggestions for using the book to locate topics. Types of writing covered include description, comparison/contrast, process, narrative, classification/division, cause-and-effect writing, exposition, argumentation, definition, research-and-report writing, creative writing, and critical writing. Ideas in the book range from the profound to the everyday to the topical--e.g., describe a terrible beauty; write a narrative about the ultimate eccentric; classify kinds of body alterations. With hundreds of new topics, the book is intended to be a resource for teachers and students alike. (NKA) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the on inal document. -

2019 Bravo Success

2019 Bravo Success Bravo #1 Among Female Viewers Bravo ranks #1 in primetime among F18-49 and F25-54 in cable. This is the third year in a row the network has earned this ranking. Bravo is also finished out 2019 as the #4 cable entertainment network in P18-49 and P25-54, its highest ranking ever. Bravo Continues to Dominate the Unscripted Landscape Below Deck Mediterranean posted the largest P18-49 ratings growth of any television series that’s been airing for the past four years. Additionally, Bravo has the most series in the top 20 reality programs on cable in 2019 on linear (with six), VOD (with six) and social (with five). Bravo Digital Posts Best Year Ever Every returning Bravo series on-demand is experiencing season over season growth based on average. VOD views per episode: Real Housewives of Atlanta S12 (+95%) Below Deck Med S4 (+38%) Real Housewives of New Jersey S10 (+38%) Million Dollar Listing LA S11 (+35%) Don’t Be Tardy S7 (+32%) Below Deck S7 (+27%) Summer House S3 (+26%) Real Housewives of Beverly Hills S9 (+25%) Married to Medicine S7 (+20%) Real Housewives Of Potomac S4 (+19%) Watch What Happens Live with Andy Cohen S16 (+18%) Vanderpump S7 (+16%) Real Housewives of Orange County S14 (+15%) Southern Charm NOLA S2 (+15%) Real Housewives Of Dallas S4 (+14%) Real Housewives of New York S11 (+13%) Southern Charm S6 (+6%) Top Chef S16 (+5%) Million Dollar Listing NY S8 (+4%) In 2019TD, Bravo has generated 230MM live streams and 452MM on-demand views (+71% and +38% YoY YTD) across all platforms (dMVPD, TV Everywhere, STB, and YouTube) The Bravo TV Everywhere app is also pacing to have its best year ever across all metrics. -

Entire Issue (PDF 3MB)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 111 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 156 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 15, 2010 No. 124 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was THE JOURNAL ANNOUNCEMENT BY THE SPEAKER called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. The PRO TEMPORE pore (Mr. YARMUTH). Chair has examined the Journal of the The SPEAKER pro tempore (Mr. last day’s proceedings and announces JACKSON of Illinois). The Chair will en- f to the House his approval thereof. tertain up to 15 further requests for 1- Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- minute speeches on each side of the DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER nal stands approved. aisle. PRO TEMPORE f The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- f fore the House the following commu- ACCEPT AMENDMENT TO MAKE TAX CUTS PERMANENT nication from the Speaker: PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE (Mr. WILSON of South Carolina WASHINGTON, DC, The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the September 15, 2010. asked and was given permission to ad- gentleman from New York (Mr. TONKO) I hereby appoint the Honorable JOHN A. dress the House for 1 minute and to re- come forward and lead the House in the YARMUTH to act as Speaker pro tempore on vise and extend his remarks.) this day. Pledge of Allegiance. Mr. WILSON of South Carolina. Mr. NANCY PELOSI, Mr. TONKO led the Pledge of Alle- Speaker, in 108 days, liberals will im- Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

STEPHEN MANLEY ______SAG-AFTRA Hair: Brown Eyes: Blue Height: 5'8'' Weight: 145 Lbs

STEPHEN MANLEY __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ SAG-AFTRA www.Stephen-Manley.com Hair: Brown Eyes: Blue Height: 5'8'' Weight: 145 lbs. Film SOUTHWEST Supporting Wanted Dead Pictures THE SURVIVALIST Lead FilmCohen COFFEE BOYS Lead Doug Nickel Prods. MULLIGAN MEN Lead Smash Films LEGION OF STRANGERS Lead Manley Ent. STAR TREK III: SEARCH FOR SPOCK Young Spock Paramount THE HINDENBURG Co-Star Universal Studios KANSAS CITY BOMBERS Supporting MGM Studios THE CAREY TREATMENT Supporting MGM Studios Television THE GROOM Groom Alvaro Collar, Spain SWITCH Guest-Star Universal Studios TESTIMONY OF TWO MEN Guest Star Paramount ERNIE AND JOAN Series Lead Paramount MOBILE ONE Guest Star Universal Studios SARA Series Lead Universal Studios THE RIVALRY Supporting CBS Studios DAYS OF OUR LIVES 2 year contract role NBC Studios CODE R Guest Star Warner Bros SIERRA Guest Star Universal Studios DUFFY Guest Star Universal Studios THE AMAZING HOWARD HUGHES Co-Star ABC Television HONOR THY FATHER Lead, MOW Universal Studios THE LAST CONVERTIBLE Lead, MOW Universal Studios FAITH FOR TODAY Co-Star NBC Studios MARRIED: THE FIRST YEAR Series Lead Lorimar Television SECRETS OF MIDLAND HEIGHTS Series Lead Lorimar Television ALOHA PARADISE Guest Star Aaron Spelling THE ROOKIES Guest Star Spelling-Goldberg BEYOND THE GALAXY Series Lead Colombia MARCUS WELBY, MD Guest Star Universal Studios THE F.B.I. Guest-Star Colombia ADAM-12 Guest-Star NBC EMERGENCY Guest-Star Universal Studios POLICE WOMAN Guest-Star Colombia STREETS OF SAN FRANCISCO Guest-Star Warner Bros KUNG FU Guest-Star Warner Bros MANNIX Guest-Star Paramount LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRE Guest Star NBC Studios THE LOVE BOAT Guest Star Aaron Spelling BARNABY JONES Guest Star Quinn Martin Pr POLICE STORY Guest Star Warner Bros YOUNG DR. -

Gal' Warnings FFFEBRUARY 2009 VVVOLUME XXIV , IIISSUE 222 Commodore’S Corner

Gal' Warnings FFFEBRUARY 2009 VVVOLUME XXIV , IIISSUE 222 Commodore’s Corner By Diane Larson Growing up in Minnesota, January was the worst month of the year for me. It was Photo by Mike Gitchell dangerously cold, gray and the Libby Gill and Nicola Lamb enjoying a winter daysail tipping point of winter where you started to feel anxious about spending so much time coordinator, and the many volunteers who helped indoors. Now that I live here, I love January and I make this a success -- great job! Top notch had a great time kicking off the year instructors were able to advance with WSA. I represented WSA at the February 10th Meeting everyone along and generate more Officer Installation dinners for Southern excitement for match racing with California Yachting Association on Capt Holly Scott and her impressive classroom discussions, January 10 and the Association of Santa adventures on The Baja effective on-the-water sessions Monica Bay Yacht Clubs on January 16. which were filmed and later used The most amazing part of these events Ha Ha in de-briefing demonstrations. is the presentation of the service 6:30 p.m. Social hour WSA extends a special thank you awards. Your jaw drops when you hear 7:30 p.m. Business to match racing instructor, Brian the achievements of each individual, Angel; US Sailing rules instructor, and we are so fortunate to have them 8:00 p.m. Speaker Bill Stump; Lido instructor, John as part of our community to inspire and Papadopolous; the Lido fleet; and admire. And, of course, it was even more special SCCYC. -

The Australian Naval Architect

THE AUSTRALIAN NAVAL ARCHITECT Volume 17 Number 2 May 2013 Marine - Professional Indemnity OAMPS Gault Armstrong is the largest marine insurance specialist broker in the Asia Pacific region 02 9424 1870 and has proven experience in providing solutions for [email protected] all aspects of marine and related insurance needs. oampsgaultarmstrong.com.au Professional Indemnity Insurance can protect your legal liability, related costs and expenses arising out of your operations as Naval Architects, Surveyors, Ship Agents, Ship Brokers and Consultants and their personal assets by providing cover against potential threats, such as claims for alleged negligence and error in the performance of professional services. Contact one of our brokers about professional indemnity insurance today. THE AUSTRALIAN NAVAL ARCHITECT Journal of The Royal Institution of Naval Architects (Australian Division) Volume 17 Number 2 May 2013 Cover Photo: CONTENTS Kat Express 2, a 112 m wave-piercing cata- 2 From the Division President maran recently delivered by Incat Tasmania to Mols Linien of Denmark 2 Editorial (Photo courtesy Incat Tasmania) 3 Letters to the Editor The Australian Naval Architect is published four times per 5 News from the Sections year. All correspondence and advertising copy should be 12 Classification Society News sent to: The Editor 13 Coming Events The Australian Naval Architect c/o RINA 15 General News PO Box No. 462 Jamison Centre, ACT 2614 31 Developing a Low-cost Vehicle/Passenger AUSTRALIA Ferry in Response to the Increased email: [email protected] Competition from Air Travel in The deadline for the next edition of The Australian Naval Ar- South-East Asia — J C Knox and C M Evans chitect (Vol.