PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capacité Issue 4

CAPACITÉ Special Feature on Combating Invasive Alien Species CAPACITÉ – ISSUE 9 In this issue of Capacité, we turn our focus to invasive alien species (IAS). Several grants in the CEPF Caribbean portfolio are addressing this issue. And with good reason too. According to the CEPF Ecosystem Profile for the June 2014 Caribbean islands hotspot, the spread of invasive aliens is generally consid- ered the greatest threat to the native biodiversity of the region, especially to its endemic species, with invasive aliens recorded in a wide range of habitats throughout the hotspot. Inside this issue: An overview article by Island Conservation provides a useful context for un- Invasive Species on 2 Caribbean Islands: derstanding the threat of IAS in the Caribbean. Fauna & Flora International Extreme Threats but shares information about its work in the Eastern Caribbean along with useful Also Good News tips on using fixed-point photographs as a monitoring tool. From the Philadel- phia Zoo we learn about efforts to investigate the presence of the fungal dis- Making Pictures that 4 ease chytridiomicosis in amphibians in four key biodiversity areas in His- Speak A Thousand paniola. Words On the Case of the 6 We also feature the field-based work of the Environmental Awareness Group Highly Invasive in Antigua’s Offshore Islands, and of Island Conservation in association with Amphibian Chytrid Fun- gus in Hispaniola the Bahamas National Trust. These field-based efforts are complemented by initiatives by CAB International and Auckland Uniservices Ltd. to promote Connecting the Carib- 8 networking between and among IAS professionals and conservationists and bean KBAs via a Virtual build regional capacity to address IAS issues. -

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology

THE J OURNAL OF CARIBBEAN ORNITHOLOGY SOCIETY FOR THE C ONSERVATION AND S TUDY OF C ARIBBEAN B IRDS S OCIEDAD PARA LA C ONSERVACIÓN Y E STUDIO DE LAS A VES C ARIBEÑAS ASSOCIATION POUR LA C ONSERVATION ET L’ E TUDE DES O ISEAUX DE LA C ARAÏBE 2005 Vol. 18, No. 1 (ISSN 1527-7151) Formerly EL P ITIRRE CONTENTS RECUPERACIÓN DE A VES M IGRATORIAS N EÁRTICAS DEL O RDEN A NSERIFORMES EN C UBA . Pedro Blanco y Bárbara Sánchez ………………....................................................................................................................................................... 1 INVENTARIO DE LA A VIFAUNA DE T OPES DE C OLLANTES , S ANCTI S PÍRITUS , C UBA . Bárbara Sánchez ……..................... 7 NUEVO R EGISTRO Y C OMENTARIOS A DICIONALES S OBRE LA A VOCETA ( RECURVIROSTRA AMERICANA ) EN C UBA . Omar Labrada, Pedro Blanco, Elizabet S. Delgado, y Jarreton P. Rivero............................................................................... 13 AVES DE C AYO C ARENAS , C IÉNAGA DE B IRAMA , C UBA . Omar Labrada y Gabriel Cisneros ……………........................ 16 FORAGING B EHAVIOR OF T WO T YRANT F LYCATCHERS IN T RINIDAD : THE G REAT K ISKADEE ( PITANGUS SULPHURATUS ) AND T ROPICAL K INGBIRD ( TYRANNUS MELANCHOLICUS ). Nadira Mathura, Shawn O´Garro, Diane Thompson, Floyd E. Hayes, and Urmila S. Nandy........................................................................................................................................ 18 APPARENT N ESTING OF S OUTHERN L APWING ON A RUBA . Steven G. Mlodinow................................................................ -

Chapter 02 Biogeography and Evolution in the Tropics

Chapter 02 Biogeography and Evolution in the Tropics (a) (b) PLATE 2-1 (a) Coquerel’s Sifaka (Propithecus coquereli), a lemur species common to low-elevation, dry deciduous forests in Madagascar. (b) Ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) are highly social. PowerPoint Tips (Refer to the Microsoft Help feature for specific questions about PowerPoint. Copyright The Princeton University Press. Permission required for reproduction or display. FIGURE 2-1 This map shows the major biogeographic regions of the world. Each is distinct from the others because each has various endemic groups of plants and animals. FIGURE 2-2 Wallace’s Line was originally developed by Alfred Russel Wallace based on the distribution of animal groups. Those typical of tropical Asia occur on the west side of the line; those typical of Australia and New Guinea occur on the east side of the line. FIGURE 2-3 Examples of animals found on either side of Wallace’s Line. West of the line, nearer tropical Asia, one 3 nds species such as (a) proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus), (b) 3 ying lizard (Draco sp.), (c) Bornean bristlehead (Pityriasis gymnocephala). East of the line one 3 nds such species as (d) yellow-crested cockatoo (Cacatua sulphurea), (e) various tree kangaroos (Dendrolagus sp.), and (f) spotted cuscus (Spilocuscus maculates). Some of these species are either threatened or endangered. PLATE 2-2 These vertebrate animals are each endemic to the Galápagos Islands, but each traces its ancestry to animals living in South America. (a) and (b) Galápagos tortoise (Geochelone nigra). These two images show (a) a saddle-shelled tortoise and (b) a dome-shelled tortoise. -

Bahamasyou’Ve Heard of Our White Sand Beaches

DISCOVER THE BIRDS OF THE BahamasYou’ve heard of our white sand beaches. Our turquoise ocean waters. But what about our spectacular birds found nowhere else in the world? The Bahamas is a sublime spot for birdwatching the whole family will love. Beauty on a wing. The vibrant birds of The Bahamas will delight you. Search for over 300 species - including 6 species found only here - in landscapes of jaw-dropping natural beauty. Ocean adventures. Take a break from watching our colorful winged residents to watch our colorful aquatic ones. Grab a mask and explore coral reefs in some of the clearest waters in the world. Or use a rod and fly to find silvery bonefish in the turquoise blue. A chance to chill. After your outdoor exploration it’s time to put your feet up and relax. And there’s no better place to sip some sunshine and let the worries of the world fall away. Pack a beach umbrella and find your slice of heaven. Fun for the whole brood. Your choice for travel needs to bring smiles to the entire family. Luckily there’s something for everyone in The Bahamas Bring your brood to explore our islands and you won’t disappoint. Maximize your birding experience with an Audubon- trained guide. Want to see more of The Bahamas’ famed birds? Embark on your adventure with a local bird guide. Trained by Bahamas National Trust & Audubon experts, our bird guides have intimate knowledge of local birds and the best locations for spotting them. Hiring a guide also helps strengthen the local eco-economy, improving livelihoods while providing incentives for communities to protect important Cuban Emerald bird habitat. -

Local Rolling Plains

Texas Master Naturalists ROLLING PLAINS NEWSLETTER Vol. 7, No. 9 http://txmn.org/rollingplains September 2015 One Backyard Hummingbird EVENTSLOCAL Species Becomes Two SEPTEMBER 1: Rolling Plains By Jennie Miller Chapter monthly meeting is at River These days, the discovery of a species usually requires treacherous treks Bend Nature Center. Location: 2200 into remote jungles untouched by science. But the world’s newest bird 3rd Street, Wichita Falls, Texas. Time: species was discovered, not in some remote tropical jungle, but in back- 7:00 PM. Program: Laura Gillis will yards in the Bahamas. A member talk about the monarch tagging of the Bee Hummingbird group, program. the Bahama Woodstar includes two subspecies which scientists SEPTEMBER 12: Sikes Lake now say should be recognized as Clean-up Location: Sikes Lake two distinct species. Time: 9:00 AM We need lots of volunteers to pull this off. We need “Much of fieldwork was con- people to supervise the students, ducted sitting at the backyard help with the hotdogs and help tables of birders, holding the re- with the trash. MSU will supply corder in one hand and a cup of tea in the other,” explained Teresa Feo, a hot dogs, drinks, bags, grabbers doctoral student at Yale University and lead author of the study, published and gloves, the chapter supplies the in the January issue of The Auk. manpower. We always have a good time and it’s a great way to spread The Bahama Woodstar species contains two subspecies, Calliphlox ev- goodwill in the community and get elynae evelynae found throughout the northern islands of the Bahamas, our name out there. -

Is Considered Globally Threatened Following the IUCN Red List Criteria

MEETING R EPORTS J. Carib. Ornithol. 18:88-93, 2005 TOWARDS A GLOBALLY THREATENED BIRD PROGRAM FOR THE CARIBBEAN 1 2 DAVID W EGE AND V ERÓNICA A NADÓN -IRIZARRY 1BirdLife International, Wellbrook Court, Girton Road, Cambridge CB3 0NA, UK; e-mail: [email protected]; 2Caribbean Program BirdLife International, Rio Canas 2107, Colorado St., Ponce, Puerto Rico 00728-1824; e-mail: [email protected] OVER 10% OF THE C ARIBBEAN ’S AVIFAUNA (57 3. Are there any priority actions that need to be of 560+ species) is considered globally threatened added to the published conservation action list for following the IUCN Red List criteria. Twelve of each species, and what level of funding would be these are Critically Endangered, 21 Endangered and required to implement the identified activities? 24 Vulnerable, with an additional 18 species Near 4. Would it be valuable for SCSCB to form a Threatened (see Table 1). These birds will be the Threatened Bird Working Group? next to go extinct (due to a number of differ- 5. What would be the focus of such a group, and ent threat factors), and thus it is our collective re- how would this relate to existing Working Groups? sponsibility to focus our attentions on their conser- vation. While conservation actions and monitoring Outputs .—The following outputs were discussed: activities are focused on some of these birds, for 1. There are 57 globally threatened and 18 near many we have no idea on a year to year basis threatened species on the IUCN Red List for the whether their status is improving or declining, or Caribbean (Table 1). -

Ornithogeography of the Southern Bahamas. Donald W

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1979 Ornithogeography of the Southern Bahamas. Donald W. Buden Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Buden, Donald W., "Ornithogeography of the Southern Bahamas." (1979). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3325. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3325 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the Him along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

WOOD-DOCUMENT-2016.Pdf (11.15Mb)

A Multi-Criteria Evaluation Model for Rapid Assessment and GIS Mapping of Ecological Values for Informed Land Use in Small-Island Developing States The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wood, Kathleen M. 2016. A Multi-Criteria Evaluation Model for Rapid Assessment and GIS Mapping of Ecological Values for Informed Land Use in Small-Island Developing States. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33797334 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A Multi-Criteria Evaluation Model for Rapid Assessment and GIS Mapping of Ecological Values for Informed Land Use in Small-Island Developing States Kathleen McNary Wood A Thesis in the Field of Sustainability and Environmental Management for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2016 Abstract Small-island developing states (SIDS) contain some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on earth (Churchyard et al., 2014), yet these countries suffer from pandemic sustainable policy failure (Mycoo, 2006), leading to significant losses in ecological assets and ecosystem services (Albuquerque & McElroy, 1992; McElroy, 2003). Many sustainability issues in SIDS arise from uninformed development practices due to a lack of economic and human resources to inform sustainable land use planning (Ghina, 2003; Douglas, 2006; Global Conference on the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States, 1994). -

Rapid Ecological Assessment of the Avian Community and Their Habitats on Andros, the Bahamas

Rapid Ecological Assessment of the avian community and their habitats on Andros, The Bahamas Prepared by: John D. Lloyd Gary L. Slater Ecostudies Institute P.O. Box 703 Mount Vernon, WA 98273 For: The Nature Conservancy Nassau, The Bahamas Submitted: June 2010 Ecostudies Institute committed to ecological research and conservation TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction......................................................................................................................... 1 Methods............................................................................................................................... 1 Results and Discussion ....................................................................................................... 3 Pine Forest ...................................................................................................................... 3 Coppice ........................................................................................................................... 4 Qualitative Assessments ................................................................................................. 5 Summary............................................................................................................................. 6 Recommendations............................................................................................................... 8 Acknowledgements............................................................................................................. 8 References.......................................................................................................................... -

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba. -

Habitat Distribution of Birds Wintering in Central Andros, the Bahamas: Implications for Management

Caribbean Journal of Science, Vol. 41, No. 1, 75-87, 2005 Copyright 2005 College of Arts and Sciences University of Puerto Rico, Mayagu¨ez Habitat Distribution of Birds Wintering in Central Andros, The Bahamas: Implications for Management DAVE CURRIE1,JOSEPH M. WUNDERLE JR.2,5,DAVID N. EWERT3,MATTHEW R. ANDERSON2, ANCILLENO DAVIS4, AND JASMINE TURNER4 1 Puerto Rico Conservation Foundation c/o International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service, Sabana Field Research Station HC 0 Box 6205, Luquillo, Puerto Rico 00773, USA. 2 International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service, Sabana Field Research Station HC 0 Box 6205, Luquillo, Puerto Rico 00773, USA. 3 The Nature Conservancy, 101 East Grand River, Lansing, MI 48906, USA. 4 The Bahamas National Trust, P.O. Box N-4105, Nassau, The Bahamas. 5 Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—We studied winter avian distribution in three representative pine-dominated habitats and three broadleaf habitats in an area recently designated as a National Park on Andros Island, The Bahamas, 1-23 February 2002. During 180 five-minute point counts, 1731 individuals were detected (1427 permanent residents and 304 winter residents) representing 51 species (29 permanent and 22 winter residents). Wood warblers (Family Parulidae) comprised the majority (81%) of winter residents. Total number of species and individuals (both winter and permanent residents) were generally highest in moderately disturbed pine- dominated habitats. The composition of winter bird communities differed between pine and broadleaf habitats; the extent of these differences was dependent broadleaf on composition and age in the pine understory. Fifteen bird species (nine permanent residents and six winter residents) exhibited significant habitat preferences. -

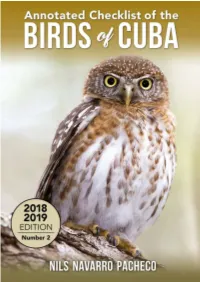

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba No. 2, 2018

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 2 2018-2019 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Cuban Pygmy Owl (Glaucidium siju), Peralta, Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2017 Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2018 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2018 ISBN: 9781790608690 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. He is a freelance author and an internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as curator of the herpetological collection of the Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he described several new species of lizards and frogs for Cuba. Nils has been travelling throughout the Caribbean Islands and Central America working on different projects related to the conservation of biodiversity, with a particular focus on amphibians and birds. He is the author of the book Endemic Birds of Cuba, A Comprehensive Field Guide, which, enriched by his own illustrations, creates a personalized field guide structure that is both practical and useful, with icons as substitutes for texts.